Pascha is the principal festival of the Greek calendar. Preparations for Pascha begin from Holy Week, and Paschal holidays start on Holy and Great Friday, when the Orthodox have permission to be absent from work and pray in church. Xenia Klimova, an expert in Greek traditions and folklore, senior lecturer at the Department of Philology of Lomonosov Moscow State University, Ph.D in Language and Literature Study, speaks about Paschal dances, traditional cakes and cookies, and other customs associated with the celebration of the Radiant Resurrection of Christ in Greece.

—Xenia, how do Greek people prepare for Pascha?

—Like in Russia, preparations begin from Holy Week. In Greek it is called «Εβδομάδα των Παθών» (that is, “the Week of Passion”, or “the Passion Week”) or «Μεγάλη εβδομάδα» (“the Great Week”). According to their custom, even those who didn’t keep the fast during Great Lent shouldn’t eat meat and milk products during Holy Week. Many people, especially the elderly, try to fast on only bread and water through this week. On Holy and Great Friday they only drink water into which they add some vinegar because the Savior was given vinegar when He was on the Cross.

Bells don’t ring on Holy Week in Greece. As Greeks say: «οι καμπάνες χηρεύουν» (“bells are widowed”).

Special preparations commence on Holy and Great Wednesday: people tidy up their homes and collect food for the Paschal meal. In rural areas priests visit villagers’ houses and bless Paschal food. Though in cities priests normally don’t visit homes of the faithful for this purpose, parishioners can come to church to have their Paschal food blessed.

Tsoureki —Do they bake kulichi on Holy Thursday, as we do?

Tsoureki —Do they bake kulichi on Holy Thursday, as we do?

—Yes, they do. And Greeks have several varieties of Paschal cakes and cookies. For example, «τσουρέκι»—that is, “tsoureki”, which is a sweet rich braided cake topped with sliced almonds.

The second most important cake is «Λαμπροκουλλούρα». Pascha in Greek is «το Πάσχα», or «η Λαμπρή», meaning “shining”, “luminous”. Hence the name of Paschal round loaf.

It is decorated in a very interesting way: there is a cross in the center, and there are various cosmogonic patterns, like birds, spirals, and herringbone patterns, on either side.

Traditionally baking Paschal bread was associated with marriage. Unmarried young women did the baking and thus demonstrated their skills as future housewives. They would arrange fairs on Pascha and choose the best Paschal bread. The maiden who baked it was considered “a good catch” (likewise, the guy who could retrieve the cross from water on the feast of Theophany was regarded as “a man any girl would marry”).

Some of interesting examples of the so-called folk etymology are connected with the most important Christian festival. “Pascha” is a lexeme borrowed from Hebrew. But in popular consciousness it is associated with the Greek verb “pascho” (πάσχω), meaning “to suffer”. Therefore, the meaning of the feast is associated with the Passion of Christ on the Cross.

—Do they color eggs on Holy Thursday as well?

—Yes, by tradition Paschal eggs are red. But nowadays (like in Russia) eggs come in a variety of colors. They say that those who are in mourning dye their eggs blue or dark purple, though I personally have not seen this.

Commercial production is developed so much in Greece that colored hard-boiled eggs are sold in supermarkets before Pascha.

—Were there any special ceremonies observed on Holy Week?

—In Thrace, for instance, on Holy and Great Thursday or Friday people made an effigy of Judas, dressed it in old clothes, carried it around the village and sang ritual songs:

Ράτσα, κεράτσα

δωσ'μια κληματσίδα

να κάψουμε τον Οβριγιό

πόχει πολλή κασσίδα.

Οβριγιός φορεί φτερό

στο κεφάλι το ξερό...

“Hey, Kind Lady,

Give us a grapevine,

We will burn down a Jew

With bad eczema,

The Jew has a plume on his withered head…”

In effect, it is a variation of the ceremony of burning a dummy of “winter” (of Maslennitsa in Russia) on Pancake Week preceding Great Lent.

—Are there Paschal holidays in Greece?

—Yes, and they last almost a week after Paschal Sunday. But in fact for many they begin from Holy and Great Friday, when people get a day off. When believers want to take their time off on Holy Friday, their employers are very understanding.

In schools and higher education institutions Paschal holidays are long enough to allow students living in Athens to travel to their native villages in the regions and back.

—How do Greeks celebrate Pascha?

—The feast begins the night before Paschal Sunday. Most Greeks come to church only to walk in the procession and then go home to celebrate the festival. Despite this, first and foremost Pascha is a religious festival for them, and they look forward to the moment when the most important event is announced: “Christ Is Risen!”

Greeks stock up on large candles beforehand. The Greek for “large candle” (for example, a Paschal or a wedding candle) is λαμπάδα. Thus, some of our terms differ. The Greek for “icon lamp” which usually hangs in front of an icon is καντήλι; the Greek for “censer” is «θυμιατήρι».

—Are Paschal candles always red?

—In Greece they are not necessarily red. When Greeks come to Russia for Pascha, they ask in amazement: “Why are your candles red?!”

—Is the Paschal meal arranged in parishes?

—No, Greeks celebrate at home. Following the festal service families gather and go to somebody’s place to eat Paschal soup, μαγειρίτσα, made of lamb pluck. As a rule, they go to the hostess who cooks this dish perfectly. This soup is not too heavy and very tasty, so it is just fine after the service. Then all go to sleep, and next morning they get up and begin the preparations for large-scale celebrations. They roast a lamb or a goat on a spit in the yard.

The μαγειρίτσα “magiritsa” Paschal soup

The μαγειρίτσα “magiritsa” Paschal soup

In Greece Paschal dinner is the most lavish meal of the year. There is even a special verb in Greek, πασκάζω, meaning approximately “to enjoy hearty and delicious food, as on Pascha”.

A wide range of dishes are present on the table: the above-mentioned cakes and cookies, colored eggs, meats…

—Do Greeks practice egg-tapping, too?

—Yes, they call it τσουγκρίζω. One member of each family becomes the winner in this “fight”. Many Greeks like to tell stories about how one or another family member tried to trick them by using a wooden colored egg instead of a chicken egg. Greeks are sure to tell you that once one uncle had allegedly beaten everybody, that they had wanted to eat that miraculous egg, but he hid it and his fraud was exposed. Similar horse stories are also widespread in the army.

—Yes, they call it τσουγκρίζω. One member of each family becomes the winner in this “fight”. Many Greeks like to tell stories about how one or another family member tried to trick them by using a wooden colored egg instead of a chicken egg. Greeks are sure to tell you that once one uncle had allegedly beaten everybody, that they had wanted to eat that miraculous egg, but he hid it and his fraud was exposed. Similar horse stories are also widespread in the army.

There is a custom in northern Greece (Thrace, Macedonia) which is called χάσκα. Χάσκω means “stare with one’s mouth open”. A Paschal egg is attached to a string and suspended from the ceiling, and the contestants should try and catch it while it is spinning. He who manages to eat this egg is called “a Paschal lucky player”.

Formerly, people used to collect eggshells and bury them under fruit trees so that they could produce more fruit.

In some regions of Greece people observe the custom of building bonfires on Pascha. Paschal fire is very important to them. Unlike Russians, Greeks don’t bring the fire of Holy and Great Thursday home but take Paschal Flame with them. If you observe the faithful walk home after the midnight service in Athens, carrying candles ignited with this fire, you will find that it is a beautiful sight.

At home people would cross their windows, doors, household, animals and fruit trees (not least the trees that wouldn’t bear fruit) with Paschal Flame.

Paschal Fire

Paschal Fire

Vigil lamps were lit from it and burned throughout the year or at least over a period of Bright Week.

The Paschal Flame is also conveyed to their neighbors—elderly and sick people, and those who couldn’t go to the Paschal service.

—How do they celebrate Pascha in Bright Week?

—Festivities continue in Bright Week. The first day is called «Δευτέρα της α γάπης»—that is, “Monday of love”. In the Greek regions where blood vengeance was widespread the ritual of αδελφοποιϊα (meaning “sworn brotherhood”, “fraternization”) was performed. Members of the feuding parties would make cuts on their own hands, mix the flowing blood, shake one another’s hands and thus become “blood brothers”. Of course, not only enemies could do it, but this ritual was above all associated with reconciliation.[1]

This custom has pagan roots (they would sometimes pour blood out into one cup and take turns drinking it), but the time chosen was Pascha. This tradition is familiar to everybody, though it has not been observed recently. It was very vividly described by Nikos Kazantzakis (1883—1957) in the early twentieth century. Some of my informants recounted how they “had sworn brotherhood” with somebody else decades ago.

On Bright Monday dancing parties were arranged in the square in front of the village church attended by the whole village.

In insular Greece, lads used to swing lasses or swing together with them in Bright Week. While swinging, they would sing mantinades—folk-style short romantic songs that contained two rhyming fifteen-syllable lines. As a rule, they were sung by guys. Sometimes a youth would compose such songs on the spot at the first try. For example:

Κούνια μου, κούνησέ μου την, για να βραδιάσει η μέρα,

να ξημερώσει, να τη δω, να πάρει ο νους μου

“O swings, rock this girl for me, so that the evening can set in and then dawn come, so that I can see her and lose my heart to her.”

And young ladies could respond:

Που να χαρείς τα χέρια σου τα μαργαριταρένια

που κούνησαν κι άλλες πολλές, τώρα κουνάν και μένα

“Admire and be proud of your pearly hands, which have swung many others and are now swinging me.”

Sport competitions are held during Paschal fairs. The winner was rewarded with the best Paschal cake baked by the most desirable prospective bride.

The festivities are normally arranged by church. Today each village has a folk society, and people try to play folk instruments, sing traditional songs and dance.

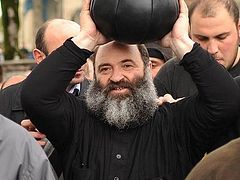

Pascha in Perachora. The 2000s

Pascha in Perachora. The 2000s

—Do priests dance too?

—Everybody dances on Pascha in Greece, and the priest is always the first to come out dancing. I used to collect local folklore in the village of Perachora in the south of mainland Greece. There are two churches there, and each family is registered in one of these parishes so it attends only one of them. On Bright Monday they would perform a spiral dance, each family in its own parish, headed by their priest. First they danced in a circle inside church, and then went outside and danced around the church. There is a road in the village which connects these two churches. So the two groups of parishioners got on the road dancing, met, danced in front of each other for some while, exchanged greetings, and walked in opposite directions towards each other’s churches while dancing, danced there, and then walked back to their respective parishes to continue their celebrations. Again, a kind of “sworn brotherhood”.

Pascha in Perachora. The 2000s

Pascha in Perachora. The 2000s

Curiously enough, now that all the old priests who used to dance on Pascha are dead, the Church has assigned new young priests to these parishes, but they refuse to dance. And old women from Perachora are absolutely displeased. They complain: “Our fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers danced, all of our priests danced, but these refuse!”

—And what do Greeks sing on Pascha? Are there any special songs, like Christmas carols?

—As a rule, these are Pascha-themed songs, but here we don’t see as much diversity as we see on the Nativity of Christ or Pancake Week. Judas is often mentioned in songs, but not necessarily.

Σήμερα Χριστός Ανέστη

καιστουςουρανούςευρέθη...

“Today Christ is our Resurrection, and He has ascended into Heaven...”

True, there are metaphors and elements of cosmogony in a number of songs. For instance, we can find a metaphor of cosmic jubilation or similes which are a typical feature of folklore: “There are youths, standing like strong trees, and young maidens, like lemon trees adorned with flowers.”

But all in all, all the texts are within the limits of Christian tradition.

—But there must be some rites in addition to what you’ve mentioned.

—For example, in northern Greece, τουλούπα was prepared on Bright Wednesday. It was a torch made of sheep’s wool. A woman would kindle a huge flame and carry it while dancing at the head of a line of dancers.

As a matter of fact, sheep are traditional “Paschal” animals. One week before Pascha people would sometimes take their lambs home for a week to fatten them up. They would give them names which were associated with the feast—for example, “Lambros” (from “Lambri”), “Paschalis” etc.

Despite varying degrees of religiousness, Pascha is still the most important feast for Greeks. In Greece it is celebrated with a greater magnificence than any other festival.