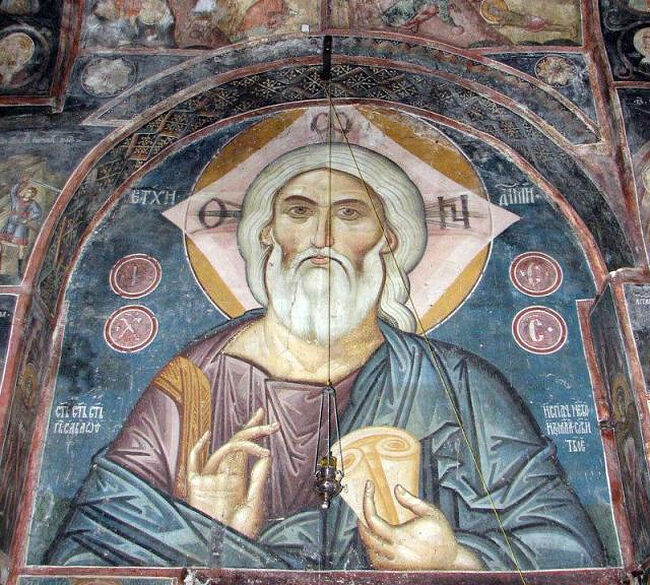

Photo: russianicons.files.wordpress.com

Photo: russianicons.files.wordpress.com

Last question: When did the world come about? There are two sides to this question, which must be distinguished by the one answering it. Let’s assume that this question is posed by God and man. How would God Himself answer it? What would He say to the question of when the world was created? He would say: “Never,” for He has no time. It can only be from our side, and there this question is impossible. Therefore, looking from above, from God, we see that the world has no beginning in time; and therefore, in this sense, it’s true that it exists from eternity—from before it is eternity, and eternity can’t be measured.1

So, it’s only according to our conception that we ask when the world was created. But does this question maintain its power even in our conception? For us, “when” means time, and by the word “world” we also include time. Therefore, asking when the world came about, we’re also asking when time came about. The question is clearly nonsense. And that the word “world” includes time is clear from the words of the Apostle Paul: By Whom also He made the ages (Heb. 1:2), where the ages or time is taken for the world itself.2 And indeed, the question is untenable. If we ask when, then before this “when” we assume a time or another “when,” and before this another “when,” and so on. Therefore, asking it this way, we’ll be looking for a beginning to eternity. The mind must agree that there was no time before the existence of the world, and therefore it can’t ask, “When did the world come about?”

This question becomes: How many years have passed, or how long do we consider the existence of the world to be? The time seems small, but even if millions of years had passed, we could propose the same question. Thus, the world came about not in tempore [in time], as St. Augustine says, but cum tempore [with time], and to ask about the beginning of time means to ask about two incompatible things. The metaphysical question here could be how eternity is combined with time. But this combination has existed already for several millennia, and therefore we can’t reject it. Holy Scripture explains the origin of the world this way, if it’s understood reasonably. It says that the world received its beginning from God and isn’t eternal.

How was God’s activity realized before? The same as now. For the world is, as it were, an echo of God’s activity, which, in fact, consists in God. His activity was exercised, as we noted before, by the work of the Son and Holy Spirit.

So, the world came about, according to Scripture, not so long ago: Its existence is considered to be about six thousand years. There will be a time when it’s counted in the millions, and people will lose track of the number, for the world will exist in eternity. But at the same time, there could be the question: Does Holy Scripture really teach that the world is so new? Isn’t Moses describing the restoration of the world? The pagans had and still have this idea. It’s based upon the fact that the existence of the world seems to be short. It’s a mysterious, but valid reason. Another reason is the fall of the angels and the briefness of the innocent state of our forefathers. If, they say, the angels fell, then there must be a time when they lived according to their former purpose; if there was a state of innocence, then it must have been prolonged. They also argue that if there was no other world before this one, then it must be supposed that the perfections of God: wisdom, goodness, omnipotence—were left idle for a long time.

Therefore, the Fathers of the Church didn’t consider it harmful to think that there was another world before this one. Thus, St. Basil the Great, in his first talk on the Hexaemeron, discusses the beginning of the world of higher spirits like this: “It appears, indeed, that even before this world an order of things existed… The birth of the world was preceded by a condition of things suitable for the exercise of supernatural powers, outstripping the limits of time,”3 and so on. Additionally, current history and geology have found many reasons to believe our earth is older. Based on them, one can come, if not to the idea that the world is eternal, then at least to the idea that it has been remade—restored. The evidence proving the old age of the world is of two kinds: historical and geological. Let’s discuss them.4

1) There’s one historical reason, namely the legends of the Chinese and Indians about the antiquity of the world and their chronology, going back much further than when we believe the beginning of the world was. But this conclusion will be strong when criticism can clarify and define these legends together with their chronology. The fact that ancient peoples, as critics have already proven in many cases, loved to praise their antiquity and trace it to the most ancient of times can work against this now. It should also be said that the legends of these peoples about the creation of the world are very similar to the story of Moses. They point to the same time, but they’ve simply increased it for known reasons.

2) Of the physical-geological reasons, the following are noteworthy: a) Architectural monuments have been found in wilderlands. For example, in America someone dug a well and found part of a brick building that none of the residents there remember. Similar discoveries have been made on the island of Ceylon; b) In Sweden, traces of a pier were found on a certain mountain. Rings were found nailed to the mountain, at which ships there were moored; c) In Switzerland, traces of bridges were found on mountaintops—a clear sign of former dwellings there; d) In the Duchy of Modena, when someone was searching for water, he found human dwellings at a depth of thirty feet, then at twenty feet—the surface of the earth, similar to what we see. Finally, agricultural products were found at a depth of twenty feet; e) The lava of fire-breathing mountains turns into earth; that is, it takes on its properties—not quickly, but after a thousand years. But eight layers of lava were found near Vesuvius; therefore, the world must have existed for eight thousand years already; f) Stalagmites and stalactites are found in caves, having formed over thousands of years. In just one cave, one was found with 20,000 layers, and that means the world must have existed for 20,000 years already; g) Corals, belonging to the genus of animal-vegetable creatures, of which there are many in the Pacific Ocean, in Australia, have multiplied so much that they’ve formed coral islands. They say this requires more time than is usually believed; h) Recently, the geologist Goutier, who dug into the earth in several places in order to learn about the interior of the globe, discovered that in America the earth’s surface has fourteen layers, suggesting as many or at least four major world epochs, because in each layer he found particular types of animals buried; i) Finally, according to astronomer’s calculations, the light from some stars can reach us in two million years. Therefore, the world must have existed for at least two million years.

But it’s not difficult to respond to all of this.

a) To the fact that many things are being discovered that people don't remember, we can say that they could have simply forgotten them. Evidence of such forgetfulness isn’t uncommon. There’s an anecdote in the description of a French expedition in Egypt in the time of Napoleon where the Egyptians, wondering why the French were looking at their pyramids with such wonder, said: “Were these pyramids built by their ancestors?” It means the Egyptians forgot that their pharaohs built them.

b) What they say about Italy isn’t surprising at all. There have always been coups there since ancient times. It’s a country as full of internal fire as external goods. It will eventually fall victim to the fire simmering within its bowels. So, there have always been revolts there, but we only know about the ones that happened after the appearance of newspapers. We did know a little earlier about Herculaneum and Pompei, but we owe this to Scripture—and the fate of these cities didn’t suddenly become known to everyone.

c) As for the remains of a pier found on a mountain in Sweden, in response to this objection I must say that the water used to be higher. The elements have become gentler now, in general; the sands thrown out by the sea often produce great upheavals. For example, when the sea water receded in one part of England and the sand on the shore fell away, an entire village with the stone walls of destroyed houses was revealed.

d) In order for lava layers to prove a specific age of the world, it must first be proven that the forces of the earth have always acted the same way. But this is impossible to prove. We see that physical forces weaken and act more slowly than they did before.5 We can see evidence now that nature used to work faster. Falling rocks, which pick up great speed in the air, are, so to speak, nature’s last attempts to express the speed of its former activity. In general, geology can’t say anything decisively, because it itself doesn’t even have any clear beginning as a science, having only recently started developing.

e) The astronomical objection comes from considering the distance of the stars and planets and the amount of time it takes light to reach us from the sun. But is this a solid foundation? Is it possible to guarantee that the law according to which light runs through a certain space is unchangeable? And that it’s changeable was proved by a Dorpat astronomer. In analyzing and observing the stars, he noticed that one was missing—but four years later he found it again. So, the light from it reached us in four years, whereas it once took perhaps four hundred years. And that this star was covered by some other body can’t be proven, because a body couldn’t cover it for so long; one body passing by another takes, for the most part, a few minutes. Astronomers have invented a hypothesis to explain the radiance of bodies. The body, they say, doesn’t shine by itself, but only has the ability to activate its electric fluid,6 while the speed of this capability can’t be defined.

Thus, there’s no historical, geological, or astronomical evidence that could be used to say that the world is older than we think. At the very least, we don’t know enough about the world to confidently determine this.