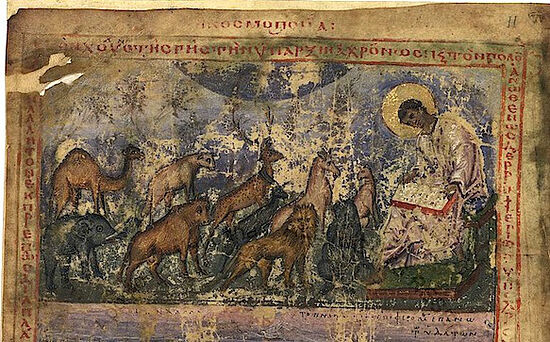

Moses writing in Eden, from the Leo Bible, an illuminated tenth-century Byzantine Old Testament

Moses writing in Eden, from the Leo Bible, an illuminated tenth-century Byzantine Old Testament

Holy Scripture not only says that the world is from God, but tracing the history of the origin of the world, it reveals the manner and order of its creation in the Book of Genesis (Gen. 1:1-31). But did the world come about the way Moses describes it? It must be so, otherwise there’d be no reason to describe it.

Doubts about this were born only later in the minds of people who wanted to see Divinely-inspired men as simple, ordinary people. When this desire took possession of them, the thought was born in them: “How could Moses have known what he wrote?” God, they said, didn’t reveal it to him; he didn’t witness it himself.1 Therefore, they argued, he wrote a story based upon a historical solution to a self-posed question about the creation of the world.

They have an entirely empty basis for their opinion. To support it, they say this story is similar to stories about it from other peoples; but this isn’t proof of anything, because they’re similar because they’re copied from Moses’ original. They further point out that there are two passages in Moses’ story (one in the first, and another in the second chapter of Genesis), showing that there are two authors. For the second passage says, or rather repeats, that Adam and Eve were created separately; but in the first—that they were created together. In the first God is named Yahweh, but in the second—Elohim. But this is a weak reason, because historians usually act this way—first speaking in general, and then stopping on the most important point and speaking about it in detail. The words “Yahweh” and “Elohim” are used by David and the other Prophets almost without any differentiation: one word in one chapter, in the next the other.

Finally, they point to some inconsistencies unworthy of Divinely-inspired men. For example, according to Moses, plants were created before the sun; and in the second passage it says the Garden was planted after the creation of man. But plants need light, and Moses couldn’t but know this. Therefore, if he himself knew, then as an intelligent man he undoubtedly wouldn’t have written it this way. If he wrote it, it means he wrote it not from himself. However, there’s no inconsistency in this: Plants were created before the sun, but there was already light on the first day, and therefore there was light that plants take from the sun. Thus, this objection is weak.

That this story is conveying history is proven firstly by the fact that the entire book is conveying history; therefore, it would have been inappropriate to put some kind of theological-physical meditation at the beginning. Secondly, by the accuracy, separateness, and distinctness that not only ancient poetic works, but even historical traditions don’t have. Additionally, other holy writers point to Moses as an historian. Moreover, if there isn’t a history here of the creation of the world (taking the word “history” in a limited sense; that is, meaning a description of this great work that we can comprehend), similar to the work itself to some degree, because we can’t describe it exactly, then this history is nowhere in revelation, whereas it’s actually very necessary for us. Thus, the attacks on Moses are completely unjustified, and his history is correct.

The main parts of the Mosaic story are the following: 1) God created the world by His Word, without material; 2) not suddenly, but over the course of six days; 3) He moved, so to speak, from the general to the particular, from the less perfect to the most perfect, from the physical to the human.

Is this order appropriate to the work itself? How, they ask, can God produce gradually? We respond that God created the world instantly, in its essence and main forces, and Moses describes the development of these original forces. Indeed, creativity can’t be gradual; but as for the formation of all created things, it could have occurred over six days. If there wasn’t such gradualness, then how would the instantaneous creation of the world be better? Only by that which would better show God’s omnipotence.

But, on the other hand, through the constant development of the world, we’re introduced to the mysteries of God and become acquainted with them. Here we can see that God loves us, showing us everything He can. Thus, there would be no benefit to us going against the gradual imagery, as our understanding and teaching follow from this image of gradual activity. On the other hand, it’s so that we would also act gradually.2 Moreover, it can’t be affirmatively said whether or not the world was capable of receiving instantaneous development. Rather, it can be said that it wasn’t. For its form is time; therefore, there must be gradualness in its activity. Destroying this gradualness would entail destroying time itself and returning the world to eternity. Before there was time, God produced the essence of the world suddenly, but once time appeared, then it immediately received its power. The ascent from the general to the particular, from the simplest to the complex, from the physical to the human is the image most worthy of God. And we see this now, for nature now observes the same process.

Why in six days—no more, no less? If it was necessary to count, then six or more days isn’t an important difference. Hence, the fullness of the world could be achieved only in six days; any further reason for this reckoning must be in the will of God. What in the will of God is the reason for seven days? We can’t say. Revelation only says that at the throne of God are seven glorious spirits (in the Revelation of St. John the Theologian), that there are seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, and accordingly seven Sacraments in the Church. Thus, the physical seven, the spiritual seven, and the moral-spiritual seven show that there must be some kind of seven-ness in God too, of which these sevens are a reflection.

And here they want to debase Moses, claiming that he directed the narrative of seven days against the seven Egyptian gods to whom the days were dedicated. Let it be so; let Moses have the Egyptian gods in mind, but it wasn’t only the Egyptians who counted seven days. Even those peoples who counted ten days still respected the number seven. The origin of this number comes from the cradle of mankind; therefore, it came to the word of Moses; the number seven was respected in antiquity. Cicero says: “Numerus septem est omnium rerum nobus” (Lat.: “The number seven is the measure of everything”). Its main origin is attributed to the Indians. Why did deepest antiquity sanctify the number seven? Perhaps it’s as some people think because of the number of seven planets?3 But the knowledge of the seven planets came later than the respect for the number seven. In general, it should be said that if a number was needed at creation, then there’s no reason for it not to be the number seven.

How should we understand these days? They say they were periods, that by the word “day,” Moses means an indefinite time. Even some of the Fathers of the Church thought this.4 This opinion, that is, interpreting them as epochs or periods instead of days, could solve all the geological perplexities about the old age of the world. But there’s no reason to move away from Moses’ narrative, which obviously means normal days, for every day is defined as morning and evening: And the evening and the morning were the first day (Gen. 1:5).5 True, the Prophets often used “day” to mean an indefinite period of time, but in these cases the whole passage has the appearance of indefiniteness.

They say: There was no sun; there was no rotation of the earth on its axis, and so there were no days. But there was probably some kind of circulation of the light created on the first day.6 For the property of light is movement, life, just as the property of darkness and coldness is inertia, deadness. And the movement of mass must have followed the movement of light—and this made up the days.

All the most ancient legends of other peoples are all essentially similar to the narrative of Moses. They all say that world came from God from out of an unseen abyss or chaos. The Phoenicians have indications of the manner of its origin by the goddess Nut. In Moses, the abyss is called tohu; others have the name toha, and there is erevot from erev.7 It’s especially noteworthy that as Moses spoke about the Spirit, that He was “nesting” above the abyss, for many this mass is presented in the form of an egg. There’s also the fact that there were plants before the sun, and the gradualness.

Is Moses’ description pure historical truth, or is there an admixture of poetry in it? This story is purely historical in the sense that its contents are a true occurrence, and not some myth, or the imagination of a poet asking himself how the world came about and then answering it with his own ideas. But this story, in this respect purely historical, is, on the other hand, mixed with anthropomorphisms, for it speaks about God, that He speaks and thereby produces the world: God said … and it was so (Gen. 1:9); also that He takes counsel, praises His work, and the like. Thus, Moses’ story is historical and anthropomorphic.

Тhere couldn’t be pure history here, because man not only can’t describe in his language, but can’t even imagine in his mind how this great work—the creation of the world—came about. Besides the anthropomorphism in the depiction, Moses’ narrative also adapts itself to human understanding—to our earthly view. That’s why the sun and moon are called great luminaries, although the latter is much smaller than the former. They’re great, but only for us, looking at them from earth—great from our earthly perspective. Moses had to depict the world according to this view. For what was the purpose of his story? Religion: He depicted the world, inasmuch it was necessary to know for religion. Therefore, having spoken briefly about the world in general, he immediately moves on to the earth and describes it in detail. In a word, he described the origin of the world, guided by the gaze of man—he described what man could have seen were he a witness to the creation of the world.

Is the world perfect? Moses often repeats: And God saw that it was good (Gen. 1:10), and in the end, he says: It was very good (Gen. 1:31). The purpose of this repetition is to show that everything that has come from God is good and perfect. Undoubtedly, Moses had in mind here the ancient opinion of the dualists about the evil beginning, and directs his narrative against it.

By the perfection of the world we mean that the world in general, and every creature in particular has everything it needs to achieve its purpose, for its existence.