Source: Apologia Pro Ortho Doxa

May 12, 2016

One difficulty I’ve articulated before is “translating” the language of the Bible into the language of Orthodox theology. I believe that the two are totally congruent, but their modes of speaking are different. The language (not substance) of Orthodox theology is the language of Hellenistic philosophy, while the language of the Scriptures is the language of Hebrew prophecy. As I’ve pointed out before, it was Paul the Apostle, the tent-builder who fulfilled the prophecy of Father Noah that Japheth would dwell in the tents of Shem. Paul was a Torah scholar and educated in the philosophers.

Orthodoxy teaches that all things were born through the Logos. There are distinctions within creation on account of distinct modes of participation in different sets of God’s energies. Since the Father always energizes in the Son, these energies (logoi) are summed up in the Logos. We were created in the image of the Logos, and the world is to be glorified through man: we apprehend the underlying rationalities, or logoi, of creation, and direct them by our wills to the service of God. That two step process is called “consecration” and it is Eucharistic because, when we apprehend a logos in union with Christ, we offer it up to God with “thanksgiving.”

This process of consecration requires wisdom. God rules the world through the Logos, and the Tree of Wisdom, the Tree of Rule, was the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. That language is the language of kingship. When Solomon prays for wisdom to “govern this people” the wisdom is to “discern between good and evil.” When Adam seized the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, he was attempting to crown himself king before he had learned the wisdom necessary to rule justly. “He who exalts himself will be humbled” so Adam was exiled from Paradise.

A person rules by the Spirit in union with the Logos. In this union, he is able to apprehend the rationalities of creation in relation to each other and thus direct them rightly towards God. Adam was not wise enough to rule properly, so he grasped the world and steered it away from God, which is why it began to die. An important point here is the association between apprehending the world and eating it. Plants are machines which turn the world into food, and man eats up the world and consecrates it to God. Both the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge were fruit-trees which a person could eat from.

According to Deuteronomy 5, the Torah is given so that Israel might learn to discern between good and evil. This creates an association between the book and the fruit. The Logos is the Language of God, and because man is the image of the Logos, man is the creature of language, capable of symbolizing the rationalities of the world in verbal terms. Thus, a principal symbol for learning wisdom is chewing on the scroll. This is the root of the dietary law that animals are clean only when they make a chewing motion.

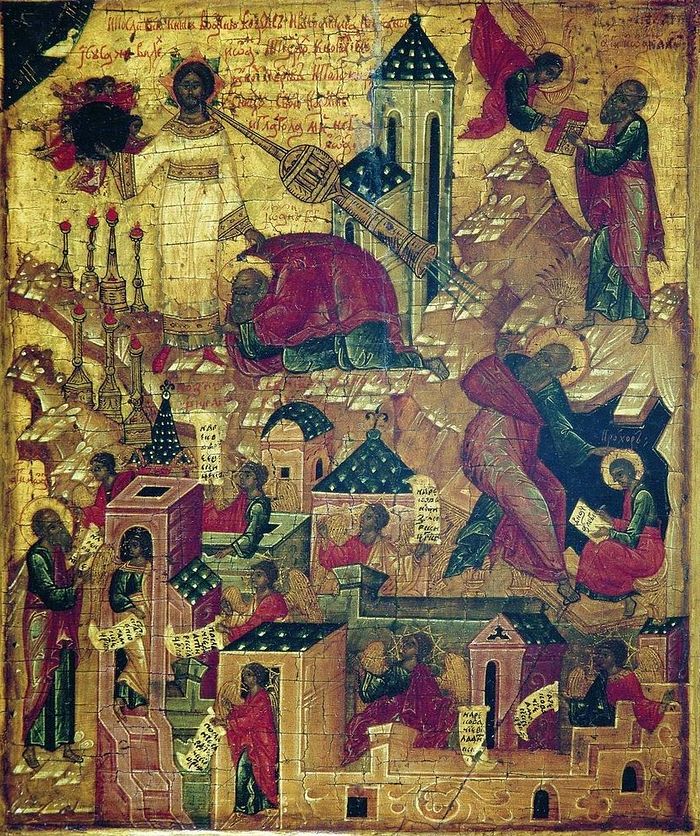

We see all these different threads come together in Revelation 4-5. John is in Heaven, and he is weeping because no person is worthy to open the book. From Adam to Christ, no person has been able to eat of the tree of knowledge rightly, to grasp the logoi of the world and direct them towards God. But an angel tells him to stop weeping, for now there is such a man. John looks, and he beholds the Incarnate Logos, the Lamb who is a Lion, ascending above the sea of crystal to the throne of God. The sea of crystal is the firmament made in Genesis 1, and it seals off the throne room of God from our material world. What John sees is the ascension of Christ. John’s Gospel ends with Jesus talking of His future ascension, but John’s narration of this ascent is in Revelation 4-5. In Christ, the Fathers teach us, our nature is placed in the throne room of God and we are seated in Heaven with Christ because we are consubstantial with Him.

Remember the association of language with the logoi, and thus the book with the summation of the logoi. The book is the fruit of the tree, and when Jesus ascends to the throne, He is made king. He is the one who is worthy to receive the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Whereas Adam exalted himself and was humbled, Jesus humbled himself and was exalted. As Paul tells us in Philippians 2:6-11, Jesus did not seize kingship, so God gave it to him. We are told similarly in the letter to the Hebrews: Jesus, in His humanity, grew up and learned the wisdom to discern between good and evil, so that He is now “crowned with glory and honor” after being “for a little while lower than the angels.”

He rules by the book. But can the book be eaten? Indeed: we see precisely this occurring in Revelation 10. The “Another Angel” is Jesus, because He displays theophanic characteristics associated with God in Ezekiel 1. He is the one who leads the whole angelic choir, the “Angel of the Lord” in the Old Testament. He gives the book to St. John: remember what he says? “Take, and eat.” This is Eucharistic language. The book symbolizes the logos, and we eat the incarnate Logos in the Eucharist, so John is given the book to chew up. When he chews up the book, he spits it out in symbols in Revelation 11-13. That’s what we are to do: meditate on God’s word, meditate on Christ, and then we symbolize all the logoi summed up by Him verbally. This is the task of theology.

Here is my point:

-The Fathers describe our task as in Christ, by the Spirit, spiritually apprehending the logoi of the world and directing them to God. This is what transfigures the creation.

-The Bible describes plants transforming the world into food, and us turning the grain-plants into bread, then eating the bread and being joined to God.

But when you understand the network of symbolic associations made within Scripture itself, you realize that the Bible and the Fathers are not roughly in the same ballpark: both of them are very precise, and they are describing exactly the same thing. Biblical theology and Patristic theology flawlessly roll together.