Blessed Prascovia Ivanovna,1 in the world Irina, was born in the early 19th century in the village of Nikolsky, Spassky District, Tambov Province. Her parents, Ivan and Darya, were serfs of the noble family of the Bulygins. When the maiden reached the age of seventeen, her master gave her in marriage to the peasant Theodore. Submitting unmurmuringly to her parents’ and master’s will, Irina became an exemplary wife and housewife. Her husband’s family loved her for her meek manners, her love of labor, and because she loved church services. Praying fervently, fleeing visitors and society, she never participated in village games. Thus she and her husband lived for fifteen years, but the Lord did not bless them with children. After these fifteen years had passed, the masters Bulygin sold Irina and her husband to the German masters Schmidt in the village of Sukrot. In five years after resettlement, Irina’s husband became sick with tuberculosis and died. Later, when the blessed one was asked what her husband was like, she replied, “He was just as silly as me.”

After her husband’s death the Schmidts took her in as a cook and bookkeeper. They tried several times to marry her off a second time, bur Irina decisively refused. “I won’t get married again even if you kill me!” So they left her alone.

In a year and a half a catastrophe occurred—two paintings were discovered missing in the nobleman’s house. The servant woman blamed Irina, trying to prove that she had stolen them. The commissary of the rural police came with soldiers, and the landowners convinced him to punish Irina. The soldiers at the orders of the commissary whipped her cruelly, broke her skull and tore her ears. But even during the punishment Irina continued to say that she had not stolen the canvases. Then the Schmidts called a local fortune-teller who said that the paintings had been stolen by a woman named Irina, but not this Irina, and that they could be found in the river. They began to search for them, and did in fact find them in the place the fortuneteller had named.

After enduring the punishment, Irina was no longer able to live with the heterodox landowners and, leaving them, went to Kiev on a pilgrimage.

The holiness of Kiev and her meetings with elders completely changed her inner state—she now knew for what and how to live. Now she desired that only God live in her heart, the only Lover of all mankind and merciful Christ, the Giver of all good things. Unfairly punished, Irina felt more profoundly the unspeakable depths of Christ’s suffering and His mercy.

The landowner at that time reported her missing. In a half year the police found her in Kiev and sent her with an armed escort to her masters. The trip was long and torturous—she had to fully experience hunger, cold, the cruel treatment of the convoy soldiers, and the crudeness of the men who arrested her.

The Schmidts, feeling guilty before Irina, “forgave” her for running away and made her the gardener. Irina served them for over a year, but having come into contact with that holy place and spiritual life, she could no longer remain in servitude, and she ran away.

The landowners once again sent out a search party, and in a year the police found her in Kiev. After placing her under arrest they sent her back under escort to the Schmidts, who, wanting to show their authority over her, did not receive her but threw her our onto the street with neither warm clothing nor a piece of bread. Having received the tonsure in Kiev with the name Parasceva, she was not saddened—she knew her path, and the fact that the landowners had thrown her out only served as a sign that the time had come for her to fulfill the blessing of the elders.

She wandered around the village for five years like a lunatic, and was the laughing-stock not only of the children but of all the peasants. She developed the habit of living year round under the open sky, enduring cold, hunger, and summer heat. Then she hid herself in the Sarov forest and lived there for over two decades in a cave that she had dug herself.

They say that she had several caves in various spots in the vast, impenetrable forest, where at the time many wild animals roamed. She sometimes went to Sarov or Diveyevo, but she was most often seen at the Sarov mill, where she came to work.

At one time Pasha possessed a remarkably pleasant appearance. After her life in the forests of Sarov and the years of ascetic labor and fasting, she came to look like St. Mary of Egypt: thin, brown-skinned from the sun, with short hair—long hair was a hindrance in the woods. Barefoot, in a men’s monastic shirt, an overcoat that was open at the chest, with arms exposed, the blessed one came to the monastery and threw into a terror everyone who did not know her.

Before she moved into Diveyevo Convent she lived a while in one village. Seeing her ascetic life, people began to turn to her for advice, and to ask her prayers. The enemy of mankind taught evil people to attack and rob her. They beat her up, but did not find any money on her. The blessed one was found lying in a pool of blood with a broken skull. She was sick for a year after this, and she never really recovered from it the rest of her life. The pain in her broken head and in her lower chest tormented her constantly, but she scarcely paid attention to it, and only every now and then she would say, “Ach, Mamenka, how it hurts! No matter what I do, Mamenka, the pain in my chest doesn’t go away!”

When she still lived in the Sarov forest, some Tartars rode past who had just robbed the church. The blessed one came out of the woods and scolded them, for which they beat her till she was half dead and broke her skull. The Tartars came to Sarov and told the guestmaster, “An old lady came out and yelled at us, and we beat her up.”

The guestmaster said, “That must be Prascovia Ivanovna.” He mounted a horse and went to get her.

Her wounds healed after the beatings, but her hair grew back unevenly, so that her head itched and she was always asking to be “checked” [for lice].

Before she moved into Diveyevo, Prascovia Ivanovna often visited Diveyevo’s blessed Pelagia Ivanovna. Once she went in and sat silently next to the blessed one. Pelagia Ivanovna looked at her a long time and said, “Yes! It’s good for you, no worries like I have; look how many children I have!” Pasha (diminutive for Prascovia) arose, bowed to her and quietly left, without having said a word.

A few years passed. One day Pelagia Ivanovna slept, then suddenly jumped up, just as if someone had woken her, ran to the window, and leaning halfway out began to peer into the distance and threaten someone.

Near the Kazan Church the gate opened, and in walked Prascovia Ivanovna, headed straight for Pelagia Ivanovna’s, muttering something to herself.

Walking up closer and seeing that Pelagia Ivanovna was saying something, she stopped and asked, “What, matushka, shouldn’ t I come?”

“No.’’

“Still early? Not time yet?”

“Yes,” Pelagia Ivanovna affirmed.

Prascovia Ivanovna bowed low to her and, without entering the monastery, went out the same gate.

Six years before blessed Pelagia Ivanovna’s death Pasha again appeared in the monastery, this time with some sort of doll, and later with many dolls: taking care of them, feeding them, calling them children. Now she would stay for weeks, sometimes months at a time in the monastery. During the final year of blessed Pelagia’s life, Pasha lived there without leaving. In late autumn of 1884 she walked past the walls of the cemetery church of the Transfiguration and, hitting her finger again at the post said, “They will go a-dying just as I’ll knock over this post; you won’t even have time to dig the graves!”

These words soon came true—Pelagia Ivanovna died, and after her, so many nuns that the forty-day prayers2 never ceased for an entire year; it even happened that they would have two funerals at once.

When Pelagia Ivanovna reposed, at two o’clock in the morning they rang the large monastery bell. The cliros nuns with whom blessed Pasha lived at the time, thinking it might have signaled a fire, were all alarmed and jumped out of their beds. Pasha arose all radiant and began to place icons all around the room and light candles.

“Well, there,” she said, “What fire? There’s no fire, just a little snow has melted here, and now it will be dark!”

Several times Pelagia Ivanovna’s cell-attendant invited Pasha to move into the reposed one’s cell.

“No, it’s forbidden,” replied Prascovia Ivanovna. “Mamenka there won’t allow it,” as she pointed to Pelagia Ivanovna’s portrait.

“I don’t see it.”

“You don’t see it, but I see it—she doesn’t bless!”

So she left, living first with the cliros nuns, and then in a separate cell near the gates. In her cell was a bed with enormous pillows, upon which she rarely lay, for dolls rested on it.

She required those who lived with her to arise at midnight to pray, and if someone refused she would make such a noise, fighting and shouting, that they would arise against their will to placate her.

In the beginning Prascovia Ivanovna went to church and watched sternly over the sisters’ daily attendance. During her final ten or so years the blessed one changed some of her rules: For instance, she never left the monastery and did not even go far from her cell; she did not go at all to church but received Communion at home, and rarely at that. The Lord Himself revealed to her what rules and way of life to follow.

Having taken tea after Liturgy, the blessed one sat down to work, knitting socks or spinning yarn. She conducted this work with ceaseless Jesus Prayer, and for that reason her yarn was highly valued in the monastery; they made belts or prayer ropes out of it. She used the knitting of stockings as a parable for exercise in ceaseless Jesus Prayer. Thus, one day a visitor came to her with the thought of moving closer to Diveyevo. She said in answer to his thoughts, “Well, why not? Come to us in Sarov, we’ll collect mushrooms and knit stockings,” that is, make prostrations and learn the Jesus Prayer.

Before she moved into Diveyevo Monastery, Pasha wandered from the monastery on far-away obediences or went to Sarov, to her beloved former dwelling places. On her travels she took a simple walking stick that she called a cane, a bundle with various things, or a sickle over her shoulder and several dolls in her lapel. With her cane she sometimes threatened people who bothered her, or who were guilty of some transgression.

One day a pilgrim came and asked to be permitted into the cell, but the blessed one was busy, and the cell-attendant decided not to disturb her. But the pilgrim insisted, “Tell her, that I am just the same as she!”

The cell-attendant was amazed at such a lack of humility and went to relay his words to the blessed one.

Prascovia Ivanovna did not answer but took her cane, went outside and began to beat the pilgrim with all her strength, exclaiming, “Ach, you soul-destroyer, deceiver, thief, pretender!...”

The pilgrim left and no longer insisted upon a meeting with the blessed one.

The sickle had great spiritual meaning for the blessed one. She cut weeds with it and, under the pretense of this work, made full prostrations to Christ and the Mother of God. If people came to her from the upper classes, with whom she did not consider herself worthy to sit, the blessed one would arrange for them to be served refreshments, bow to their feet, and leave to cut weeds—that is, to pray for them. She never left the cut weeds in the fields or in the monastery yard, but always gathered them and took them to the horse stable. As an omen of some unpleasantness she would give her guest burdock or spiny pine cones....

She prayed her own prayers, but she knew certain prayers by heart. She called the Mother of God “Mamenka behind the glass.” Sometimes she would stop as though rooted to the spot before the icon and pray, or kneel wherever she happened to be—in the field, in her room, or in the middle of the street—and pray fervently with tears. Sometimes she would go into the church and put out all of the candles and lampadas near the icons, or she would not allow the lampadas in her cell to be lit. Requesting the Lord’s blessing for every step and action, she sometimes asked loudly, then answered herself, “Should I go? Or wait?... Go, go quickly, silly!”—and then she would go. “Should I pray some more, or finish? St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, is it good that I ask? Not good, you say? Should I leave? Leave, leave, quickly, Mamenka! I hurt my finger, Mamenka! Should I have it fixed? No? It will heal by itself!”

During the days when she was struggling with the enemy of mankind she would begin to talk without pause, but it was impossible to understand her; she broke dishes and other things, worried, shouted, and argued. One day she woke up in the morning upset and worried. After midnight office a visiting noblewoman came to see her, greeting her and wishing to talk with her, but Prascovia Ivanovna shouted and waved her arms. saying, “Go away, go away! Don’t you see, there, the devil? They cut off the head with an axe, they cut off the head with an axe!” The visitor was frightened and left, not understanding anything, but soon the bell was rung to bring to news that an epileptic nun had died during a fit in the hospital.

One day the virgin Xenia from the village of Puzina came to the blessed one to ask her blessing to join the monastery.

“What are you saying, girl?!” the blessed one yelled. “First you need to go to Petersburg, and serve all the noblemen; then if the Tsar gives me money, I’ll build you a cell!”

In a little while Xenia’s brothers began to divide the inheritance, and she again came to Prascovia Ivanovna and said, “My brothers want to divide the inheritance, and you don’t bless me! As you like, I won’t obey you, and will build a cell.”

The Blessed Pasha, troubled at her words, jumped up and said, “What a silly girl you are! Well, the nerve! You see, you don’t know how many infants are more important than we are!” Having said this, she laid down and stretched out. In the fall Xenia’s relative died and a girl, a complete orphan, was left in her care.

One day Prascovia Ivanovna went to see a priest in the village of Arzamas, at whose house at the time a psalmist was on liturgical business. She went up to him and said, “Lord! I beg you, get a good wet nurse or some nanny.”

And what do you know? The psalmist’s previously healthy wife got sick and died, leaving an infant.

One of the peasants of the nearby village bought some cement sand. He was offered several extra pounds for free; he thought about it and took it.

“A lot richer you’ll be for obeying a demon! You’d do better to live by the truth that you lived by!...”

When the new church was being built in Diveyevo, Abbess Alexandra decided not to ask a blessing from blessed Prascovia Ivanovna.

A solemn prayer service was taking place at the site of the building, when the Abbess’ aunt Elizabeth came to see Prascovia Ivanovna. She was old and hard of hearing. She said to the blessed one’s novice, Dunya, “I will ask, and you tell me what she answers, otherwise I won’t hear.”

She agreed.

“Mamashenka, they’re donating a cathedral to us.”

“A cathedral, a cathedral,” Prascovia Ivanovna replied, “ But I had a look: wildberry trees are growing in the corners, they could knock the cathedral over.”

“What did she say?” asked Elizabeth.

“Why say it?” Dunya thought. “They have already laid the foundation for the cathedral,” and she answered, “She blesses.”

The cathedral was never finished.

One bishop came to the monastery. She expected him to come to her, but he went on to the monastery clergy. She waited for him until evening, and when he came she flew at him with a stick and tore the veil on his klobuk. He hid out of fear in Mother Seraphima’s cell. When the blessed one fought she was so fearsome that she made everyone tremble. Later some men attacked the hierarch and beat him.

One Hieromonk Iliodore (Sergei Trufanov) came to see her from Tsaritsyn. He had come with a procession, along with many people. Prascovia Ivanovna received him, sat him down, then took his klobuk off of him, his cross, and all his medals and awards, then put them all in her trunk, locked the lid and tucked the key in her belt. Then she asked that a box be brought to her, where she planted an onion, watered it and said, “Onion, grow tall....” and then she lay down to sleep. He sat there crestfallen. He was supposed to begin the Vigil, and he could not stand up. It was good, at least, that she had tied the key to her belt and was lying on the opposite side, so that they could untie the key and take everything out of the trunk for him.

A few years passed and he cast off his priestly rank and renounced all of his monastic vows.

One day Bishop Hermogenes (Dolganov) came to her from Saratov. He had just had a great misfortune—someone had thrown a child to him in his carriage with a note saying, “Thine own of thine own.”

He ordered a large prosphoron and went to the blessed one with the question, what should he do? She grabbed the prosphoron, threw it at the wall, so that it bounced off and hit the room divider. She didn’t want to answer. On the next day, she did the same thing. On the third day she locked herself in, and did not even come out to greet the hierarch. What to do? He so respected the blessed one that he did not want to leave without her blessing, even though matters in his bishopric demanded his attention. Then he sent a cell-attendant. She received him and gave him tea. The hierarch asked through him, “What should I do?” She answered, “I prayed and fasted for forty days, then they sang the Pascha.”

Her words meant that apparently, all of his current sorrows needed to be endured with dignity, and they would resolve themselves successfully in their own time. The bishop took her words literally, went to Sarov and lived there for forty days, fasting and praying, and during that time his problem dissipated.

Sometimes Prascovia Ivanovna would begin to make a fuss, and to the nuns who came to see her she would say, “Get out of here, you rascals, this is the cashier.” (After the monastery closed, her cell was turned into a cash-bank.)

One time, Eudocia Ivanovna Barskova, who never joined a monastery, bur never got married either, went on a pilgrimage to Kiev. On the return trip she stopped in Vladimir, at the house of one blessed merchant who received all pilgrims. In the morning he called her, blessed her with a picture of the Kiev Caves Lavra and said, “Go to Diveyevo; there Blessed Pasha of Sarov will show you your path.

Dunya3 flew as on wings to Diveyevo. During Dunya’s entire two-week trip (she had walked nearly two hundred miles) blessed Prascovia would come out on the porch, sighing and waving her arms, saying, “Ay, my little droplet4 is coming, my servant is coming.”

She arrived in the evening, after Vigil—and ran straight to Prascovia lvanovna.

Mother Seraphima, the senior cell-attendant, came out and said, “Go away, girl, go away. We’re tired, come tomorrow, after the early Liturgy.

They led her out to the gate, and Prascovia Ivanovna wailed, “You’ re sending my servant away. Why are you sending my servant away? My servant has come! My servant has come!”

In the morning Dunya came to the blessed one; she met her, spread out napkins on the bench, blew away the dust and sat her down, began to serve her tea and to treat her. Dunya remained with the blessed one. Prascovia Ivanovna immediately entrusted her with everything, and the senior cell-attendant, Mother Seraphima, came to love her.

Nun Alexandra (Trakovskaya), the future abbess, asked Dunya, “Aren’t you afraid of the blessed one?”

‘‘I’m not afraid.”

As soon as Mother Alexandra walked away, the blessed one said, “She’ll be a mother.” (That is, an Abbess.–Auth.)

Every night at twelve o’clock Prascovia Ivanovna was given a hot samovar.

She would only drink tea if the water in the samovar had been brought to a boil, otherwise she would say, “It’s dead,” and would refuse to drink it. Incidentally, when she would pour a cup of tea she would seem to forget about it, and it would cool off. When she had drunk a cup, and even when she hadn’t, she would then light and put out candles all night. She prayed all night until morning in her own manner.

Mother Raphaella related that when she joined the monastery, she often had to keep the night watch. She could easily see Prascovia Ivanovna’s cell from far away. She saw every night at twelve o’clock in the blessed one’s cell candles being lit, and the blessed one’s figure moved quickly around, now putting candles out, now lighting them. Raphaella wanted very much to see how the blessed one prayed. Having received a blessing from the sister who kept watch with her to walk along the lane, she headed in the direction of Prascovia Ivanovna’s house. The curtains were open in all the windows. Stealing up to the first window, she had just tried to climb onto the cornice to peek into the window, when an arm quickly pulled the curtains shut. She went to the second window, to the third, and the same thing was repeated. Then she went all the way around to another window where the curtains were never closed, and the same thing happened. Thus she never saw a thing.

A little time passed and Mother Raphaella came to see the blessed one, who received her and said, “Pray.”

Mother Raphaella began to pray on her knees. “Now lie down.”

Then the blessed one began to pray herself. What prayer it was! She suddenly became transfigured, raised her arms, and tears screamed copiously from her eyes; it seemed to Raphaella that the blessed one rose into the air—she did not see her legs on the ground.

Mother Raphaella also told how a half-year before the death of her mother she had gone to Prascovia Ivanovna. The blessed one started peering in the direction of the bell tower, but there was nothing there.

“They’ re flying, flying, there, one after another, higher, higher,” and she clapped her hands, “and higher still!”

Mother Raphaella immediately understood. In a half year her mother died, and in another half year her grandfather.

When Raphaella joined the monastery, she was constantly late for services. She went to the blessed one, who said, “A good girl, but she’s a lay-about. Mother prays for you.”

Schema-Archimandrite Barsanuphius of Optina was transferred out of Optina Monastery and appointed Archimandrite of Golutvin Monastery. He became very ill, and wrote a letter to Blessed Prascovia Ivanovna, whom he had visited, and in whom he had great faith. Mother Raphaella brought the letter. When the blessed one heard the letter, she only said, “Three hundred sixty-five.” In exactly 365 days the elder reposed. This was confirmed by the Elder’s cell-attendant, who was present when the blessed one’s answer was received.

When they brewed her tea, she waited for an opportunity to seize the packet and pour the whole thing into the teapot. She would empty it completely, then not drink the tea. When they poured in the tea leaves, she would try to knock their arms so that more poured in; then the tea would brew very strong, and she would say, “The broom, the broom.” She would then pour all of that tea into a wash bowl, and dump it outside. Eudocia took one rim while the blessed one took the other saying, “Lord, help us; Lord, help us,” as they took the bowl outside. When they had carried it onto the porch, the blessed one would pour it out saying, “Bless, Lord, on the fields, on the meadows, on the dark oak groves, on the tall hills.”

If someone brought jam, they tried not to give it to her directly, and if she should happen to receive any, she would take it straightway to the cleaning room and turn it upside-down into the washtub chanting, “Swear to God, from inside, swear to God, from inside.”

Dunya related that the blessed one loved her very much and treated her like a friend. Dunya would intentionally come up to the blessed one without a headscarf. The latter would immediately take out a new one and cover her head with it. In a little while she would come to her again bareheaded. Mother Seraphima commented, “Dusya,5 you’ll take all of her scarves that way.”

But Dunya gave them away to others.

Prascovia Ivanovna was occupied with people all day long. Her monastic cell-attendant, Mother Seraphima, read Prascovia Ivanovna’s entire cell rule for her. Prascovia Ivanovna was tonsured into the great schema, but she had no time to read her rule, so Mother Seraphima read her own monastic rule as well as the schema rule for Prascovia Ivanovna. Mother Seraphima had a separate cell in the monastery. For appearances’ sake she had a bed with a feather mattress and pillows, on which she never lay; she only rested in an armchair. The two of them lived as one soul. It was better to offend Prascovia Ivanovna than Mother Seraphima. If you should offend her, then it was best not to come anywhere near Prascovia Ivanovna.

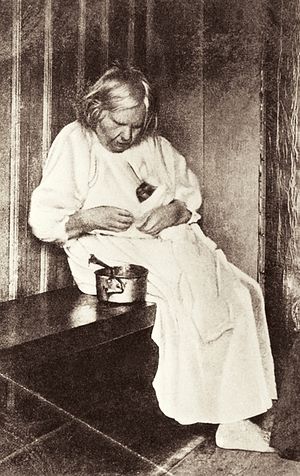

Blessed Pasha of Sarov (center) on the porch with Archimandrite Seraphim (Chichagov) and cell attendant Nun Seraphima. 1890s. Photo: nne.ru

Blessed Pasha of Sarov (center) on the porch with Archimandrite Seraphim (Chichagov) and cell attendant Nun Seraphima. 1890s. Photo: nne.ru Mother Seraphima died of cancer, and her illness was so torturous that she rocked on the floor from pain. When she died, Prascovia Ivanovna went to the church. The sisters immediately took note of her, for by that time she rarely went to church. But she said to them, “You foolish ones—you look at me, but you don’t see that she has three crowns.” This was about Mother Seraphima.

On the fortieth day, Prascovia Ivanovna waited for the priests to come and serve a Pannikhida in her cell. In the evening she waited, but they passed by, and she became upset, saying accusingly,” Ech, priests, priests ... passed me by... If they would just swing a little incense, my soul would be consoled.”

One day Eudocia had a dream. There was a beautiful house and a room with what they call Italian windows—very large. The windows were open into the garden; extraordinary apples hung from the trees, even knocking against the window, and everywhere it was dressed and swept. She saw Seraphima, who told her, “Let me show you the place where Prascovia Ivanovna is.” Then she awoke and went to Prascovia Ivanovna; but when she tried to tell the blessed one she covered her mouth...

Notwithstanding the many miracles that people witnessed during the seventy years following the repose of St. Seraphim of Sarov, there was resistance to the opening of his relics and his canonization. They say that the Tsar insisted upon the canonization but almost the entire Synod was against it, the only supporters being Metropolitan Anthony (Vadkovsky) and Archbishop Cyril (Smirnov).

During that time, blessed Prascovia Ivanovna fasted for fourteen or fifteen days, not eating anything, so that she could not even walk, bur crawled on her hands and knees.

Some time during the evening Archimandrite Seraphim (Chichagov) came and said, “Mamashenka, they won’t let us open the relics.”

Prascovia Ivanovna said, “Take my hand; let’s go out in the open.”

Mother Seraphima took one arm and Archimandrite Seraphim the other.

“Grab a tool. Dig on the right—there are the relics.”

The investigation into the relics of St. Seraphim was conducted on the night of January 11, 1903.

During that time in the village of Lomasov, eight miles from Sarov, a fiery glow was seen in the sky above the monastery and, crossing themselves, the witnesses ran there to ask about it. “Where did you have the fire? We saw a glow.”

But there was no fire. Only later did one hieromonk quietly say, “Tonight a commission came and opened the remains of Father Seraphim. Only St. Seraphim’s bones remained, and the Synod was confused. What should they do? No incorrupt relics, only bones. One eldress who was still alive at the time and knew the Saint said then, “We bow down before miracles, not bones.” There was talk amongst the sisters that the Saint himself appeared to the Tsar, who then used his authority to insist upon the opening of the relics. When it was decided to canonize the Saint and open the relics, grand princes came to Sarov and Diveyevo to blessed Prascovia lvanovna.

At that rime in the Royal Family there were four daughters, but the boy heir had not yet been born. They came to the Saint to pray for the granting of an heir. Prascovia Ivanovna had the custom of showing everything with the dolls, and now she was preparing a boy-doll. She made him a bed out of scarves that was soft and high. “Quiet, quiet, he’s sleeping,” she would say. Everything that she said was relayed to the Tsar by telephone, and he himself came later.

Eudocia Ivanovna told how Mother Seraphima was getting ready to go to Sarov for the opening of the relics, but she suddenly broke her leg. Prascovia Ivanovna healed her.

It was revealed to the blessed one that after the Tsar had been greeted in the abbatial quarters, and they had sung him a concert, he would seat everyone to breakfast but he himself would come to her.

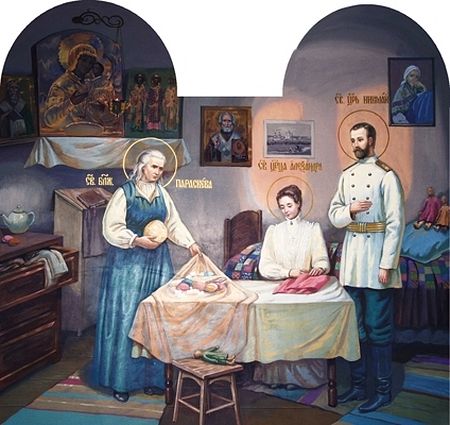

Tsar Nicholas II visits Blessed Pasha of Sarov. Wall painting in the Kazan Church at Diveyevo Monastery. Photo: nne.ru

Tsar Nicholas II visits Blessed Pasha of Sarov. Wall painting in the Kazan Church at Diveyevo Monastery. Photo: nne.ru Mother Seraphima returned with Dunya from the reception, and Prascovia Ivanovna would not allow them to clean up anything. There were potatoes in the skillet and the samovar was cold.

While they argued with her they heard from the shed, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on us.” In walked Nicholas Alexandrovich and Alexandra Feodorovna.

Already in their presence, the others laid out the carpet, cleared the table, and brought in a hot samovar. Everyone left, except the Royal couple and Prascovia Ivanovna, but their Highnesses could not understand what the blessed one was saying. Soon the Tsar went out and said, “The senior among you, please come in.”

The discussion took place in the cell-attendant’s presence, who related later that the blessed one told the Tsar, “Your Highness, come down from the throne yourself.”

When they began to part, Prascovia lvanovna opened the chest of drawers. She took out a new tablecloth, spread it on the table, and started setting out food; linen cloth of her own work (she spun her own thread), a new lump of sugar, colored eggs, and some sugar in pieces. She tied it all up in a bundle very firmly, with several knots, so that when she had tied it she had to sit down from the exertion. She then gave it to him, saying, “Tsar, carry it yourself.”

She herself stretched out her hand, saying, “And give us some money, we need to build a hut.”6

The Tsar had no money with him. He immediately sent for some, and he gave her a wallet of gold coins, which was then taken directly to the Abbess.

When Nicholas Alexandrovich left, he said that Prascovia lvanovna was a true slave of God. Everywhere, everyone received him like a Tsar; only she treated him like a simple human being. Prascovia Ivanova died on September 22/October 5, 1915.

Before her death she was always making prostrations before the Tsar’s portrait. She herself was already physically unable to do so—the others lifted her up and set her down.

“Why, Mamashenka, do you pray so to the Tsar?” “Sillies. He will be higher than all the Tsars.”

She said of the Tsar, “I don’t know ... a monastic saint, I don’t know ... a martyr.”

Not long before she died, the blessed one took down the portrait of the Tsar and kissed his feet with the words, “My dear one is already near the end.”

The blessed one died a long and difficult death. She was paralyzed just before death. She suffered very much. Some were amazed that such a great slave of God would die with such suffering. It was revealed to one of the sisters that through these sufferings she bought the souls of her spiritual children from hell.

When the blessed one was dying, one nun in Petersburg went out onto the street and saw how Prascovia Ivanovna’s soul rose up into the heavens.

From Igumen Damascene (Orlovsky), New Confessors of Russia (Platina: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 1998).