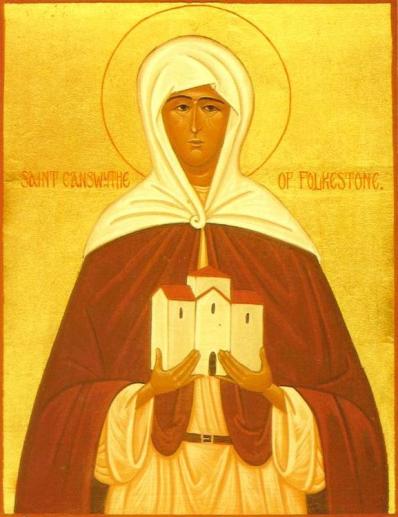

St. Eanswythe (also Eanswith, Eanswide and pronounced Inswith) has from time immemorial been venerated as “the spiritual mother of Kent” and “the wonderworker of Kent.” The center of her veneration is Folkestone—a seaside resort and fishing town on the south-east coast of Kent, on the very edge of England. It is here that her holy relics have been located for over 1350 years despite a period of several centuries’ neglect. Let us recall her life.

Few sources give evidence of this saint’s life. The Venerable Bede of Jarrow does not mention her in his History of the English Church and People, which is the case with several other early important saints who lived before him. However, St. Eanswythe is mentioned in the reliable manuscript of the mid-eleventh century known as the Kentish Royal Legend and in the Life of St. Werburgh of Chester that was compiled late in the eleventh century by the learned monk Goscelin of Canterbury. Her Life is also described by a later author, the fourteenth-century chronicler John of Tynemouth, who wrote the history of the world from creation till 1347 and compiled the lives of 156 early saints of the British Isles.

The future saint was born in about 614 to the royal family of the Kingdom of Kent. Her parents were Eadbald, King of Kent (616-640), and his wife, Queen Emma (formerly a princess of Austrasia in Gaul). Eadbald was a son of the holy King Ethelbert of Kent and his wife, the saintly queen Bertha. St. Ethelbert was the first English ruler to meet the Roman mission headed by the future St. Augustine of Canterbury on their arrival in England in 597. He became the first English Christian king and did much to make his Kingdom Christian and thanks to St. Ethelbert, Kent became the most powerful early English kingdom at the time. Thus, Eanswythe was granddaughter of such important saintly figures as Ethelbert and Bertha. Her brothers were Earconbert (King of Kent from 640 to 664 and father to St. Ermenhild, the first English king to order the destruction of pagan idols and the observation of Lent by his subjects) and Eormenred (King of Kent jointly with Earconbert for some while after 640; among his children were several saints, notably St. Domneva of Thanet).

The holy King Ethelbert died in 616 when St. Eanswythe was two years old and Eadbald succeeded his father as king. According to St. Bede, Eadbald did not wish to become Christian for some while after his accession to the throne and thus the kingdom was under serious threat from paganism. Moreover, he had married St. Ethelbert’s last wife, that is, his own stepmother, which was normal for a pagan, but a sin in Church law. Finally, through the efforts of St. Laurence of Canterbury, the successor of St. Augustine as Archbishop, Eadbald was enlightened by the light of Christ and voluntarily abandoned paganism and was baptized. From that time on he supported the Orthodox Faith.

Eanswythe led a very pious and holy life from childhood. At a very young age she firmly decided to remain a virgin and serve her Heavenly Bridegroom—Christ. It was said of Eanswythe that she loved God so much that she despised the riches of this world with all her heart and mind understood the depths of the Holy Scriptures and thirsted for the Heavenly Kingdom above all things. Beyond doubt, the future saintly maiden of God was under the influence of the spiritual disciples and successors of St. Augustine: St. Laurence of Canterbury, St. Mellitus (the first recorded Bishop of London), and St. Justus (the first Bishop of Rochester). She also had a saintly aunt, St. Ethelburgh, who married St. Edwin and became Queen of Northumbria. After the conversion of St. Edwin to Christianity Ethelburgh labored together with him to spread Orthodoxy in the north of England and after her husband’s martyrdom she returned to Kent to found a convent at Lyminge.

Eadbald wanted his daughter Eanswythe to marry a Northumbrian prince too, in order to secure friendly relations with this northern kingdom which grew as strong and powerful at the time as Kent. He saw that his sister’s (Ethelburgh’s) marriage to a Northumbrian (though at that time Northumbria was divided into Deira and Bernicia) ruler was a success, so he wanted to continue this policy. But the will of God was different. St. Eanswithe refused point blank to marry any prince and anyone in general, wishing to live as a nun. Eadbald tried to persuade her, but all in vain. Thus, about the year 630, St. Eanswythe, with the support of her father, founded the first convent on English soil, on the white cliffs of Folkestone in Kent.

Eanswythe became the first English nun in the country’s history. According to some sources, before founding Folkestone St. Eanswythe had travelled to Gaul to the convent at Faremoutiers to prepare for the monastic life. Her convent at Folkestone was dedicated (most probably by St. Honorius, the then Archbishop of Canterbury) to the Apostles Peter and Paul—a very common dedication in England of that age. From that time and until her death Eanswythe never left this convent, leading an exemplary holy life in it. With time she probably became the abbess of Folkestone though there is not enough evidence to prove this.

The community consisted partly of English nuns and partly of nuns from Gaul who were more experienced and at first helped Eanswythe and her sisters with advice. Apart from everyday monastic labors and obediences at the nunnery, the favorite practices of Folkestone nuns were repentance, perpetual prayer and praising the Lord for His mercy, especially on account of the growth and development of the Orthodox faith in the English land. The saint prayed in the church and in her cell, read the Holy Scriptures and other spiritual books and did manual labor. The holy maiden together with her sisters cared for the sick, poor, homeless and needy. Most probably they also copied and bound various manuscripts which was a custom in many English monasteries.

St. Eanswythe gained fame as a wonderworker. There are several cases of her miracles which are known: firstly, she returned sight to a blind woman by her prayers; secondly, she restored the mental health of a mad man; thirdly, a holy spring with healing properties gushed forth at her intercessions which provided fresh water to her community and the saint even commanded it to flow upstream from a mile away (unfortunately, the spring disappeared when the sea subsequently eroded the area); fourthly, she forbad birds to steal corn from the convent fields and they obeyed her.

St. Eanswythe reposed in the Lord at the very young age of twenty-six, on August 31 (September 13 according to the new calendar), 640; her father, King Eadbald, died in the same year. After the death of Eanswythe life in her community continued to prosper until the ninth century. Interestingly, it was her holy aunt, St. Ethelburgh, who established (most likely) the second convent for women in England in the neighboring Lyminge, only some three years after Eanswythe had founded Folkestone. This county of Kent situated in the south-eastern corner of England indeed produced very many (no fewer than forty!) saints alone, and it had a number of important Orthodox monastic communities in the early period, such as Canterbury, Reculver, Minster-in-Thanet, Minster-in-Sheppey, Lyminge and Folkestone.

The convent in Folkestone was ravaged by the invading Danes in about the year 865 and monastic life ceased to exist there for quite a long time while the ruins were submerged by the sea. The relics of the holy virgin then were transferred to a church further inland. In 927 the right-believing King Athelstan restored the church (though not the convent) at Folkestone and for some while it was used as a parish church with the relics of St. Eanswythe enshrined inside. Presumably there was a small community of priests attached to it who guarded the shrine and gave spiritual guidance to the local inhabitants.

After the Norman Conquest in 1095 a Roman Catholic monastery (a priory, to be more exact) of Black Benedictines in honor of the Mother of God and St. Eanswythe was built on the site of the former Orthodox convent but very soon the cliff on which it stood fell into the sea (the proximity to the sea was a problem for a number of other English monasteries and cathedrals in the middle ages—most of them were eventually washed away by the waves and destroyed, so new structures had to be built further from the shore afterwards). In the first half of the twelfth century the monastery church was completely rebuilt some distance from the sea and it is basically the same church of the Mother of God and Eanswythe which stands in Folkestone today, although, of course, it is now a parish church.

On September 12 (September 25 according to the new calendar), 1138, the relics of St. Eanswythe were translated into the newly-built Norman church and from that time on this date became her second official feast day, along with August 31. The veneration of St. Eanswythe and of her relics continued during the Catholic period of the English Church at the new monastery and numerous pilgrims visited her shrine, seeking healing, consolation and inspiration. During the English Reformation initiated by Henry VIII the monastery in Folkestone was closed, as was the case with other monasteries and convents in the country, and the saint’s relics were temporarily lost. As we said, the main monastery church of Folkestone is now used as the town’s parish church (there are three parish churches there).

A miracle occurred in June 1885 at this church during restoration work. A lead casket with human remains (as it appeared, these were the bones of a young lady, as a later expertise proved) was discovered in the north wall of the temple. The casket was dated to the twelfth century, the time of the translation of St. Eanswythe’s relics, and it was understood that the reliquary with the holy maiden’s remains was hidden during or after the Reformation from the royal commissioners so as to save them from destruction. Thus the precious relics of the first English Orthodox nun and abbess were preserved and rediscovered over three hundred years later! The holy relics of St. Eanswythe who lived and labored and prayed much for the establishment of Orthodoxy on English soil at its earliest stage rest inside this church to this day, and Orthodox Christians organize pilgrimages to this place. This is a very rare situation for modern England when the relics of a local saint are kept in their original location, and in Eanswythe’s case this has been uninterruptedly so for over a millennium.

In his fundamental work, Britain’s Holiest Places, Nick Mayhew Smith writes:

If you do visit the church, it is an effort to identify the actual site of St. Eanswythe’s bones. There is a shrine chapel dedicated to the saint, with candles and prayers, on the south side of the chancel. But her actual body lies on the opposite side, next to the high altar, in an unmarked safe. To find the shrine, stand in front of the high altar at the sanctuary rail. Look for two brass doors on your left, set in the alabaster wall. The large one is actually a bookcase with a small icon of St. Eanswythe resting on it. The smaller door, square-shaped and near the floor, contains her reliquary. It was uncovered in 1885 during building work… The bones have been returned to the same niche where they were hidden at the Reformation, and lie there today. They were examined in 1980 and confirmed as the remains of a young woman, all the bones having belonged to the same person. The vicar in charge when the relics were first uncovered, Canon Woodward, used to expose the bones each year on St. Eanswythe’s patronal festival, September 12. His enthusiasm proved too much for some of the congregation,[1] and the casket is now kept locked away. Despite overwhelming historical precedent, the idea of celebrating saintly ancestors in Christian worship is still too much for some churchgoers. However, the Greek Orthodox community in Folkestone holds services beside St. Eanswythe’s relics and donated the icon that stands alongside.

The Church of the Mother of God and St. Eanswythe stands in the center of Folkestone. After the dissolution of the monasteries it fell slowly into disrepair. It is due to the priest Matthew Woodword who served there from 1851 till 1898 that the church was restored. It is this Victorian-era restoration that gives it its present glory, especially inside, with high-quality stained glass, wall-paintings, murals and mosaics. The church tower is of the fifteenth century, and its churchyard forms a small park. The patron-saint, St. Eanswythe, is commemorated inside this church nearly everywhere, with a large number of stained glass windows, paintings, and at least two banners dedicated to her, in addition to her Orthodox icon, chapel and relics in the chancel. In the church visitors can find images where the saint is depicted with her holy well, telling birds not to damage the crops, and ministering to the needy. Among other English saints on the stained glass are St. Augustine and St. Ethelbert.

Holy Mother Eanswythe of Folkestone, pray to God for us!