In our time, many laypeople ask the question: Why should people of the twenty-first century act according to rules written by monks and for monks in deep antiquity? Why should they read monastic books in which there isn’t even a remote mention of the problems that we face today?

Here it is, the fourth Sunday of Great Lent, dedicated to a monk who lived one and a half millenia ago. Just how relevant are the writings of St. John, abbot of Sinai, to the twenty-first century? Could there really be something of value? We asked Archpriest Sergei Pravdoliubov, Priest Dimitry Shishkin, and Deacon[1] Valery Dukhanin for answers to these questions.

“All the main problems of human life are rooted in our passions and sins, with which we do not know how to struggle.”

Deacon Valery Dukhanin, doctoral candidate in Theology, pro-rector of the St. Nicholas-Ugresh Monastery:

—I immediately recall the words of the famous psychologist William James, who after reading the ascetical words of St. Isaac the Syrian, said, “This is one of the greatest psychologists in the world!” It turns out that the holy ascetical fathers who lived in ancient times knew the mysteries of life and puzzles of the human soul better than the most famous psychologists of our world.

The writer Nicholai Gogol’s desktop reference book was The Ladder by St. John Climacus. Gogol often turned to it for answers to the problems of his spiritual life. And when the famous philosopher Ivan Kireyevsky, who had had a fascination with Hegel and Schelling, took the book, Patericon, into his hands at the request of his deeply religious wife, he was so astounded at the wisdom of these simple patristic sayings that from that moment on he dedicated himself to the Orthodox Church. So, we see that representatives of secular culture marveled at the profundity of the writings of the holy fathers, and saw authentic wisdom in them.

Of course, the writings of the holy fathers are not entertaining literature that carries the soul away into an alluring fantasy. Patristic writing is read with effort, but it introduces a grace-filled world into the soul, opens our eyes to our own state, and tells us what we need to do.

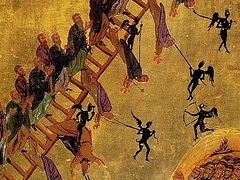

What is the relevance of the writings of St. John Climacus for our times? If we think about it, all of the basic problems of human life are rooted in our soul, in our passions and sins, and we often do not know how to struggle with them. How can we bring order into our own souls? This is what St. John Climacus wrote about. We don’t have to think that The Ladder is a super-monastic book of instruction; there is much in it that is important for all Christians in general. Much is written there about repentance and the struggle with the passions, which is especially important during Great Lent. For example, St. John said that at the Last Judgment we will not be accused for not performing miracles, or for not theologizing, or not having spiritual visions, but we will be accused if we did not bring forth repentance for our sins. St. John beautifully describes the development of the passions and the means for warring with them. In General, the Christian takes from The Ladder what is most important—the need for the soul’s constant turning to God, cutting off from ourselves with discernment everything that harms our eternal salvation. The Ladder of St. John Climacus without a doubt brings benefit to every Christian, no matter what times he lives in.

* * *

“Asceticism irritates and even angers some people, because it disrupts the momentary comfort that doesn’t want to know anything about eternity.”

Priest Dimitry Shishkin, rector of the Church of the Protection of the Mother of God in the village of Pochtovoe, Bakhchesar region (diocese of Simferopol, Crimea).

The main problem of our times is man’s loss of understanding of his higher calling. More and more the idea is spreading in the world that the meaning of human life consists in living here, on earth, with the maximum comfort and happiness. And by happiness is meant some average set of emotional-physical joys and conveniences. Having “waved away” the ascetical experience collected by the Church over the centuries, man handicaps himself, makes his life catastrophically truncated, because he rejects help in the most difficult and most important work—discovering the fullness of love and harmony with God. Moreover, having completely immersed himself in emotional-fleshly life, man completely loses the true concept of spiritual life. He may even know about it from books, can think about it and discuss it, but no more than that. This is because the living experience of discovering the grace of the Holy Spirit, the experience of growing in the knowledge of God is acquired in no other way than by “love for the very venerable commandments and sacredly fulfilling them.” Without this experience, eternal grace-filled life becomes a certain culturological fact, and nothing more.

Any arch-complex and ultra-modern problem, if we look at it strictly, has its own spiritual dimension. And the laws of cause and effect in spiritual life have not changed since the time of Adam and Eve. Only the external trappings change. The holy fathers’ deep penetration into the essence of human life is just what’s needed to help each one of us to better understand ourselves, to make sense of the causes of many personal problems, and find the path to their proper resolution.

The written experience of ascetic life is under no circumstances an example for mindless imitation, but rather a spiritual compass toward which all we Christians should strive, by which we should test all the many forms of our emotional and bodily life. You could call it a spiritual lighthouse that enables us to stay on course and not get lost forever in the darkness of this mad world.

Departure from an understanding of the true dimensions of human life, from the awareness of what it should be in eternity, leads to a person’s shameful shallowness. The person lowers himself to the level of an irrational creature, differing only in that every irrational creature knows no sin, because it abides within the boundaries determined for it by the laws of nature. But a man who has become an irrational beast sins by defiling himself, by trampling the image of God in himself. And this question, the question of the dimension of life itself, is an eternal question. That is, having the calling to attain perfection and sanctity, hearing the call to became an heir to the Kingdom of Heaven, everyone should consciously make their own choice, and respond to that call hear and now. And this call is a perfect, eternal, and irrevocable given for every person, relative to which we will spend our earthly lives in time.

An emotional-fleshly way of life means man’s renunciation of his own higher calling, the lack of desire to clearly and honestly look to the future. Reaching for God unavoidably presupposes self-limitations, and conscious restraint from sin. An experience of Christian life reveals to us such limitless heights unimaginable to us as long as we do not make this choice and begin, with God’s help, to embody, to realize this higher human calling—“to be co-participants in Divine nature.”

This is why the God-bearing elders, monks, who lived many centuries ago and put all their effort into attaining oneness with God, become inevitably close to every believing person. These ancient monks preserve and transmit to us not dead rules, words, and letters, but a living and true experience of acquiring meaning and fullness, the unutterable joy of human life.

In the Psalter are these words: With the elect man wilt thou be elect. Knowing more about one or another saint, reading his works, we enter into communion with him, and make a spiritual connection; this is not a metaphor but the reality of a higher order, because there is none dead in God. Besides being alive in eternity, the souls of the saints are filled with great grace for their faithfulness to Christ, for their ardent love and yearning for Him. What is more—and very important—they have experience of bodily life with all its sorrows, temptations, sicknesses, and even falls, but also repentance and the knowledge of truth. When we through prayer or reading their Lives and the works of the holy fathers enter into association with them, we at least to some degree participate in their sanctity, their grace, and gain them as helpers and living intercessors before God. Every attentive Christian can tell about examples of help from one or another saint in all kinds of work and situations, when a person even if briefly but ardently prayed to that saint for help. And these are not exclusive or rare cases, but it could rather be said that they are the norm of Christian life.

When we learn about the life of such a great saint as St. John Climacus, we first of all must understand that his sanctity is to a great extent exclusively the result of faith, many labors and sufferings, tears, and overcoming obstacles. And every word he said is truly worth its weight in gold. But St. John’s exposition of ascetical experience is not only his personal experience, but in the broad sense, the story of man’s ascent to God, linked with the torturous transformation of fallen nature for the sake of acquiring a supernatural, paradisal state. And this call to sanctity, the path of ascent to God, is something that touches every one of us, regardless of what times or circumstances we live in, regardless of whether we believe or not—because there is the reality of a higher order to which we can relate in different ways, but which we are not capable of changing or eliminating.

It is precisely for this reason that the teachings of such great saints as John Climacus irritate or even anger some people—this teaching disrupts the organic, momentary comfort that doesn’t want to know anything about eternity, or the grandeur of our human calling. It reminds us of the calling that no one can wave away and for which each of us, one way or another, will have to answer. It is precisely the need of an answer, if not the recognition of it, then the feeling of its imminence that irritates those who do not want to know anything about this calling, who would like to remain irrational (read: irresponsible) animals, albeit endowed with reason, will, and the ability to express themselves in human language. But speech is a divine gift, which indicates a speaking person’s living connection with a speaking God, and the possibility of a reasonable answer to the most important questions of existence.

St. John Climacus dedicated not only his entire conscience life to learning the path of human ascent to God, but he also applied every effort in his power to actually perform this work of ascent; to respond to that Fatherly call, and, by God’s mercy but also with extreme effort on his own part, to attain the goal of human life: “To enter into the joy of our Lord”. This astounding, difficult, much-sorrowful, but also bright and joyful experience of ascent is what the great St. John Climacus narrates to us. And this narrative is not a history of events in former times, but a revelation about our nature, our calling, and the way to make this ascent happen. Here everything is very specific, exact, and clear. If only we would not remain deaf, if only we would respond to the divine calling, if only we would begin to walk this path—and the Lord in His mercy and love for us, through the prayers of St. John Climacus, will not abandon us. He will support, strengthen, and teach us. If only we would strive for Him, seek Him, and apply efforts to acquire His grace, remembering that this is only possible for us “in Christ Who strengthens us.”

That is why St. John says that being a Christian means, “for a man as much as possible to emulate Christ in words, deeds, and thoughts, sacredly and immaculately believing in the Holy Trinity.”

Let us remember this, let us check our lives against the priceless experience of great ascetics, let us remember our Christian calling, which is the highest, brightest, and most joyful calling there can be on earth!

* * *

“Open the book, delve into the reading, and you yourself will understand whether there something here of value to us.”

Archpriest Sergei Pravdoliubov, rector of the Moscow Church of the Life-Giving Spring in Troitse-Golenischevo:

—Laypeople who ask why they should read books written many centuries ago and follow their instructions apparently know very little about history and do not suspect that, for example, the compendium of Roman laws that have come down to us in reworked form by the Byzantine Emperor Justianian (+565) are still the foundation and precedent of modern law. Physics, mathematics, and music have their origins in Greek antiquity; philosophy, of course profoundly revised and developed in our European forms, hails from there also. The interrelationship with God and the spiritual struggle with the earthly and fleshly are as old as the world. Apparently our young laypeople studied well in secular school and have accepted uncritically a rather superficial idea of constant progress, not only scientific and technological but also spiritual and moral. This is worth pondering attentively.

But we will not talk about that now. We will talk only about one thing. With respect to God, in a person’s spiritual life very little has changed over the past many centuries. We can even note that in distant times people were much healthier, had much greater integrity in their outlook, resolve, and activeness in ascetic labors; they strove to know the Truth through them more ardently and purposefully than our last few generations.

In this question: “Why should we read monastic books in which there isn’t a remote mention of the problems that we face today?” is an absolutely false conviction, taken from nowhere and presented as an axiom. What problems are they talking about? Perhaps they mean the conditions of life in a large metropolis, transportation problems, genetically modified produce, pension funds, or the tension of the workday, which conflict with the demands of a monastic rule and the observation of a strict fast? Could we possibly find the answers to these questions from St. John Climacus (+649)?

Of course not! All of these modern life circumstances are not at all the most important things in relationships with God, in knowing how to pray, in preserving our minds from distraction, in knowing how not to get offended and judge our neighbor. How do you preserve peace in your soul when your friend (who is also a believer) suddenly attacks you? Does it all have to do with spiritual life and contrition of heart? We can find the answers to these very questions in the works of the ancient ascetics—they reached such heights in this that we cannot even imagine. It is for these answers—about the simplest things, about how to take the first steps in the work of salvation—that we turn to the monastic saints, the experienced and proven Teachers of that deep antiquity. No one has ever said it or taught it better than them. And if someone has found something better, please share it with us—we would gladly read it.

When I was still a schoolboy, during Great Lent my father advised me to read the first volume of the Philokalia. I read it with great interest and attention. Even then I was surprised at a simple fact: Why does reading these thoughts and counsels, expounded with brilliant laconism, absolute compactness and without any superfluous words, produce an inexpressible joy, quiet, and calmness in my soul? Where does it come from? After all, we are essentially reading elementary instructions for using one or another means for the struggle with our sins. That’s all! Why does this joy and satiety of soul arise that never comes from reading other instructions—using a refrigerator, vacuum cleaner, or washing machine? Experienced people especially caution that we must not be interested in reading only theory—we must definitely patiently try to labor and fulfill in practice, under the guidance of an experienced spiritual father, the simplest requirements of the Gospel and take the primary steps, about which Abba Dorotheus (+late fourth century) and St. John Climacus wrote, and to which could well be added the attentive reading of the first volume of the works of St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov; +1867)—Ascetical Experiences, and then The Path to Salvation by St. Theophan the Recluse (+1894). Then the reader will gradually understand that these venerable monastic fathers and hierarchs are as if contemporary to us; they are closer to us than many, many people around us today and now.

After all, where God is, where there is talk of God, we enter into a completely different reality—the state of eternity in the fullest sense of the word. We come into contact with eternity, while being within linear time. As they say, sub specie aeternitatis. We live both there and here at the same time. Such a state happens at every Divine service in church, especially during Divine Liturgy. Incidentally, this state is reflected verbally also in the text of the Liturgy, if we listen attentively to the text read and sung. When we read the Holy Scripture, especially the Gospel, we hear and perceive the words of God Himself, our Lord Jesus Christ. Could they get old? This is by definition impossible. And the words of St. John Climacus are not artistic literature, and not even poetry talking about the eternal, which could quite noticeably get old together with the world, times, or eras that gave birth to them. The words of St. John Climacus are the result of many years of experience in striving for God. Every word he says about this has colossal weight not only in meaning but also spiritually. Such words can light a fire in the soul, inspire it, give it strength, and support it in times of despair. Especially since the text of The Ladder is the response to an insistent request from another abbot—The Ladder was written not according to self-will and at a creative impulse, but as an active, outstretched hand of help to other monks, in the process of obedience, which is very important in ascetic literature. We mustn’t forget that according the rubrics, The Ladder is to be read during the services of Great Lent; that is, it has been raised to a particular level—not just cell or home reading but an all-Church reading, almost on the level of Holy Scripture (like the continual reading of many psalms in the Psalter). Thus, in the text of The Ladder there is not “something of value to us” but something precious, or priceless.

This can be easily proven by experiment. Just try this: Sit at the table, collect your thoughts, and write down a few phrases or sayings that you feel are necessary to write. Let it be something you’ve experienced and thought about, or even suffered over. Set this page aside for a week and then take it and read it objectively, as if someone else had written it. You will be amazed at how lightweight the text is. Was it really worth writing down, will people receive it, will it help them? Then immediately open The Ladder and read two or three sayings. There will be such a contrast that you will get the urge to rip up your own note and throw it away. But the ancient text will amaze you with its profound content and powerful energy, which reaches through the ages to us from the sixth century.

You can also try comparing your text with the text of, for example, St. Andrew of Crete (+740). He was born eleven years after St. John Climacus died. Why is his Great Canon so loved and is and read and heard with such attention and contrition of heart? This is an amazing mystery. In 1998, it fell to me to compose a canon for the glorification of one of the New Martyrs who was very dear to me—this was required for his canonization. Having studied the Great Canon for ten years, I wanted to emulate St. Andrew and compose a Trinitarian for every ode in the canon to the New Martyr. I wrote it in a creative heat. Everything was correct and dogmatically impeccable. But how flat and primitive the Trinitarians turned out! I was unspeakably amazed. But why? St. Andrew’s are permeated with strength and energy, radiating grace, but mine were like empty candy wrappers! But I thought to myself, “Have you spent thirty years in monasticism and ascetic labors? Have you suffered in the struggle with your passions for at least a few years? Or spent at least five years in prison camp? And you want your text to be filled with power and to sound just like St. Andrew of Crete? Do you now understand what is sanctity and ascetic labor, expressed in the text?! Now be convinced and sure what your words mean, whether one can pray with them and receive through them grace-filled help.” Now everything is immediately put into place: Creative writing is one thing, and a work is quite another.

Finally, on the mighty effect of God’s Word on a person. In the summer of 1935, a twenty-one-year-old youth named Anatoly was arrested without warning. Before leaving his home he asked permission to part with his grandfather, Archpriest Anatoly (+1937; glorified in 2000; commemorated December 10/23). The youth asked his blessing before leaving for a long time, perhaps forever. His grandfather rose from his desk, looked somehow triumphantly at his grandson, folded his fingers in blessing and said distinctly and with authority: “Remember, Anatoly: Rejoice in that day and leap for joy, because great is your reward in heaven! (Lk. 6:23)” The young Anatoly spent five years in prison camp, in hard and grievous conditions, and was then freed. He remembered these words all his life and repeated them to his children. He said that these words of his grandfather’s were for him an almost tangible physical support. They upheld him, and he endured everything through them, existed by them. He weathered everything through the grace-filled power and energy of these holy words spoken to him by a future priest-martyr.

Thus do the words of the monastic saints and ascetic hierarchs have such effective and mighty power, upon which we can almost physically lean, pass with them through all obstacles and abysses without stumbling, and receive the salvation and life with God that we so need. Just open the book and delve into the readings, and you yourself will understand whether there is really anything of value to us in this.