The Midlands commonly refers to the central counties of England, including Warwickshire, Northamptonshire, Leicestershire, Rutland, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Staffordshire, the West Midlands metropolitan county and Worcestershire; it is still today characterized by manufacturing industries. Historically it was a part of the largest early English kingdom of Mercia, which stretched as far to the east as Lincolnshire and western Cambridgeshire and as far to the west as Cheshire and Shropshire.

Mercia was one of the last English kingdoms to adopt Orthodox Christianity in the seventh century. The first Mercian king to embrace the faith of Christ was Peada, who briefly ruled its southern part until his murder on Easter in the year 656 with the involvement of his treacherous wife. The first Christian king of all Mercia was Wulfhere, who ruled from 658 till 675. This kingdom was Christianized mainly by Northumbrian monks and missionaries. Numerous early Orthodox churches, monasteries and convents existed in Mercia. Many saintly men and women—bishops, abbots and abbesses, priests, hermits and holy laypeople—lived in this region during the “Age of the Saints”. However, if we look at the coastline of England from all sides we will discover that far more saints performed their spiritual labors in the coastal areas. And it is no wonder, because it was in accordance with the spirit of early English and Celtic saints to settle on the coast, on peninsulas and offshore isles. Nevertheless, the English Midlands has its wealth of ancient relics and shrines. Let us talk about two ancient Midland saints whose veneration by Orthodox and other Christians is still alive.

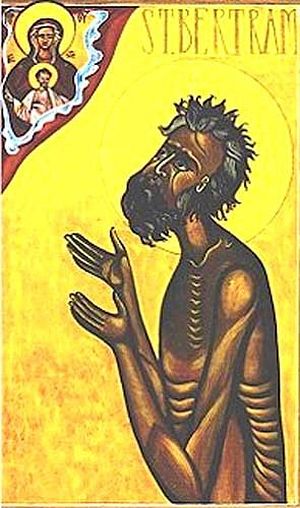

Righteous Bertram (Bettelin) of Ilam

Commemorated August 10/23

It is a very remarkable fact that there are at least two early English saints who are especially venerated by modern Russian Orthodox believers and of whose lives we know virtually nothing except that they actually existed, were holy, and have performed many miracles over the centuries. These saints are Sts. Wite (Candida) of Dorset and Bertram (also Bettelin) of Ilam, to whose shrines pilgrimages are organized, and whose miracles are still plentiful. Who was St. Bertram?

Our holy father Bertram, hermit and wonderworker of Stafford and Ilam, lived in the seventh and eighth centuries. There is no early hagiography of Bertram; however, there is a late post-Norman narration of his Life, which is not very reliable but is based on earlier traditions. All that we know for certain is that this holy man lived for many years as a recluse and anchorite in the wooded and hilly districts of what is now Staffordshire and was greatly venerated both in his lifetime and after his death. According to much later narrations, he was born into the royal family of Mercia but preferred the service of Christ to a secular life of power and luxury.

According to later legend, in his younger days he made a trip to Ireland, where he fell in love with a local princess and married her. The couple returned to England when she was pregnant. A sudden tragedy that happened in the forests of the Midlands put an end to the couple’s happy life and called Bertram to live as a hermit: When once the saint left his wife and their newly-born baby to get some food, they were both killed by wolves. The probable site of the incident was the tiny present village of Wetton in north Staffordshire within the Peak District national park and the valley of the River Manifold. Widowed, Bertram decided not to remarry but to dedicate the rest of his life to God and service to people. At first the young ascetic led an exemplary holy life, settling on a (now non-existent) isle near the present-day industrial town of Stafford in Staffordshire, where he brought many pagans to Christ by the miraculous and grace-filled power of his preaching.

Seeking a more secluded life, he moved to the hilly area near the present-day hamlet of Ilam on the border of Staffordshire and Derbyshire, where he remained till the end of his life, living as a true “desert father” in total isolation, holiness and communion with God. In the eighth century this area was a wilderness, so it was a haven for an ascetic who wished to live amid forests and hills and communicate only with God and angels. According to medieval legends, the devil tried to tempt the righteous man more than once. Thus, the evil one attempted to suggest that he (Bertram) must turn stones into bread by his prayer. Instead of this, the man of God started praying so that bread could be turned into stones. True or not, according to the evidence of 1516, the parish church at Barthomley housed several stones believed to be the same “St. Bertram’s stones”. Many people came to Bertram, who was venerated and loved for his wisdom and asceticism, seeking for his spiritual counsel. The hermit turned nobody away and consoled all who came to him, but above all our saint treasured his seclusion. The holy man would often retreat to a hidden cave near Ilam for quiet prayer.

After the saint’s repose, many miracles occurred by his prayers at his miracle-working relics over many centuries. Of the history of the original church in the picturesque village Ilam we know little. But it is a true miracle that so many holy objects have survived on this holy site to this day despite the bloody Reformation. This village (in fact, a handful of houses) still preserves a parish church, a shrine, crosses, two holy wells and a cave associated with St Bertram. The physical presence of his relics is argued about, but his spiritual presence on this very holy spot is evident for everyone who visits it. The church is dedicated to the Holy Life-Giving Cross and retains features of the Norman and Early English Gothic styles (for example, its tower is of the thirteenth century). The reliquary of St. Bertram which presumably (it is still not proven) houses the saint’s relics stands in St. Bertram’s chapel within this church. Like all medieval shrines, it has holes on its sides at the base so that pilgrims can reach them and put their sick body parts into them. Paper prayer requests are submitted in this Anglican church and read out at the shrine during services, a practice which is very close to the Orthodox tradition. This reliquary is the major focus of pilgrimages. Its main structure is from the fourteenth century, whereas its cover may be from as early as the ninth century. This chapel was purposely built by 1618 and is a true gem of this church. However, the church boasts a number of other early treasures, notably a Saxon font. This font has carvings which are believed to depict scenes from Bertram’s Life. Figures of men, dragons, and the Lamb of God with a cross can be discerned on it. Some other minor structures are Saxon—for example, a doorway on the south side.

One of the two holy wells of St. Bertram in Ilam, Staffs. Photo: Neil Theasby from Geograph.org.uk).

One of the two holy wells of St. Bertram in Ilam, Staffs. Photo: Neil Theasby from Geograph.org.uk). Outside the church, the churchyard has two surviving Saxon crosses, and one of them has several much eroded carvings presumably of Viking origin. These crosses date back to the time between the eighth and eleventh centuries and are most likely former Mercian “preaching crosses”. Two holy springs associated with St. Bertram can be found nearby. One of them sits just to the south of this church; its water, at least until recently, was used for baptisms, and it has a wide stone chamber. However, another well, located further away from the church, is considered more holy and directly linked with the saint (perhaps he blessed it and drank from it himself). Doubtless, it has preserved its healing properties from earliest times. This well is used by Orthodox believers for prayer services to this day. One of these wells lies under a tree which is referred as “St. Bertram’s ash tree”. There also used to be a “healing tree” near one of the wells. The River Manifold, which flows nearby, can be crossed by St. Bertram’s Bridge. There is an ancient cave in the vicinity of Ilam that is reputedly the very cave where our saint performed his spiritual labors. This cave is not easy of access; it is over four miles northwest of the village in the wild landscape. Regular annual pilgrimages are organized to Ilam and all its shrines, especially Orthodox pilgrimages of various jurisdictions (Russian, Greek, Antiochian). It is one of the most visited early English shrines of central England.

Ilam is closely associated with the wealthy landowner, industrialist, and Member of Parliament Jesse Watts-Russell (1786-1875). The beautiful setting of Ilam reminded him of the Alps, so he decided to change the area a little. He literally moved the village and resettled its residents in newly-built “Swiss-style” houses a mile away from the church. Then he rebuilt the famous attractive Ilam Hall stately home and laid out the Italianate garden near it (the hall still exists and is used as a youth hostel, tea-rooms, shop, information center, etc). This man founded a local school, too. He and his family are commemorated in the Holy Cross church where Watts-Russell built a chantry-chapel and mausoleum to his father-in-law, David Pike Watts. Thanks to J. Watts-Russell, Ilam became a gem within the popular Peak District national park. The local Dovedale House is occasionally used as a venue for Orthodox conferences and meetings. Ilam village has its own village cross, and there is another small ancient cross some distance away on the site of an early battle.

Among other places of veneration of St. Bertram let us mention the village of Longnor in north Staffordshire. The local eighteenth-century St. Bartholomew’s Church has an interesting landmark: a modern sculpture of Bertram of Ilam, created by the contemporary sculptor Harry Everington (1929-2000). Residents of Stafford—the county town of Staffordshire—consider Bertram their heavenly patron. This town has a very large, old and interesting collegiate Church of St. Mary the Virgin. Bertram was said to have lived as a hermit on its site before moving to Ilam. He erected a wooden chapel and a cell on this spot, and after his death the chapel was rebuilt in stone and enlarged. This chapel, on the site of his hermitage, was famous in the Middle Ages and was attached to the church’s west end. However, it was later converted into a school and finally pulled down in 1801. In the mid-twentieth century excavations were carried out near the tower of St. Mary’s, and the foundations of the stone chapel associated with Bertram were discovered. Beneath them parts of the original timber structure were dug out, complete with a very early wooden cross that may have been used by Bertram himself.

Many saints are venerated inside the Anglican Church of St. Mary; notably St. Chad of Lichfield. Among its numerous treasures let us mention a huge font in a style similar to the Greek with unusual carvings on it and a monument to the writer Izaak Walton (1593-1683), the author of The Compleat Angler—practical information on fishing with folklore, interspersed with pastoral songs—who was born locally and baptized in this church. The Anglican parish church in the village of Barthomley in Cheshire near the Staffordshire border, mentioned above, is dedicated to “St. Bertoline”, who is generally identified with Bertram. It is the only surviving church dedicated to our saint. The nave and the tower of the current church are of the fifteenth century, while the rest of its fabric is later. A terrible event happened within its walls in 1643 during the English Civil War: The Royalists massacred a group of twelve supporters of the Parliament as they hid inside it. This church purportedly houses a couple of ancient stones in the Lady Chapel that are attributed to the above-described miracle of Bertram. Notably, several years ago the Antiochian Orthodox parish of the Archangel Michael in Audley (Staffordshire) acquired a stone from this parish church for safekeeping as a relic and in return gave it an icon of St. Bertram.

Area of the former Norton Abbey in Cheshire.

Area of the former Norton Abbey in Cheshire. A small Catholic Augustinian priory in honor of the Mother of God and St. Bertram was founded in 1115 in what is now the industrial town of Runcorn in Cheshire on the south bank of the River Mersey. It was moved to the neighboring settlement of Norton in 1134, and towards the end of the fourteenth century was raised to abbey status. It housed the so-called “Norton cross”, which had healing properties. The monastery grew larger but was dissolved under Henry VIII in 1536. Today “Norton Priory” is a museum within the town of Runcorn containing many remains on the territory of the former medieval monastery with gardens of an eighteenth-century country house. Extensive excavations carried out on the territory of this monastery revealed many interesting details of its life and finds. It is reckoned to be the most important monastic site in Cheshire and one of the most excavated former monastic sites in Europe. Among the most important finds there are a magnificent fourteenth-century sandstone statue of the Martyr Christopher and large sections of medieval tiled floor of fine mosaics. An Orthodox service to St. Bertram in English was composed some time ago.

Passion-Bearer Prince Alcmund (Alkmund) of Derby

Commemorated: March 19/April 1

Prince Alcmund (Alkmund) was a son of King Alchred of Northumbria (ruled 765-774) and his wife Osgifu. In 774, as a result of a palace revolution in Northumbria, the young Alcmund was forced to flee to Scotland where he preached the Good News to the Picts for many years. His father was exiled there as well. After his prolonged exile to Scotland, the Northumbrians called on Alcmund to return to his native land because the dynastic struggles were over. The saint of God came back but the troubles soon resumed. According to some sources, Alcmund participated in battles for freedom that took place not only in Northumbria, but also in Mercia. However, about the year 800 he was assassinated at the hands of murderers at the orders of the Northumbrian usurper Eardwulf (ruled 796-806). Such post-Norman authors as Florence of Worcester, Simeon of Durham and pseudo-Matthew of Westminster, who mention Alcmund, testify that he was slain by the usurper’s henchmen. A number of medieval authors claimed that he was martyred by the Danes, but the Danes attacked England only a century later.

In any case, after this, Alcmund was venerated as a passion-bearer—a saint who was not necessary martyred for his religious beliefs, but who voluntarily gave his life for the truth. In his lifetime Alcmund was loved by many for his humility, and was famous for his acts of charity and generous support for the needy, widows, and orphans. This saint was venerated by English ordinary folk for his good deeds and noble death, and no fewer than six ancient churches were dedicated to him. He is particularly venerated in Shropshire and Derbyshire. In the Shropshire village of Lilleshall, where his body originally rested and numerous miracles occurred at his relics, the earliest church was dedicated to Alcmund. With time the wonderworking and sweet-smelling relics were translated to the city of Derby (originally called Northworthy), now the administrative center of Derbyshire. It was done to protect them from the raiding Vikings.

According to tradition, when the saint’s shrine was opened in Derby an unearthly fragrance spread all through the church and lingered there for many days. The deaf, the blind and those suffering from different diseases received miraculous help at his shrine. In the early tenth century the precious relics of Alcmund were translated to the town of Shrewsbury in Shropshire. They were greatly venerated in this town as well, and a famous parish church was later dedicated to him there. In the twelfth century (around 1140) the holy body was brought back to Derby, and many miracles occurred during the journey. The relics were laid in a church in Derby that bore the saint’s name, and they remained there until the Reformation, venerated by thousands of pilgrims who flocked to them for healing and consolation.

After the Reformation the official veneration of saints was forbidden. In 1846, the old St. Alcmund’s Church in Derby was rebuilt and again consecrated in his honor. However, by the middle of the twentieth century its bell-tower had started to crumble. Meanwhile, the city’s Catholic community expressed their discontent that the high spire of this Anglican temple was “blocking the view” of their Catholic church of St. Mary. In 1968, during the construction of an inner ring road that ran through the site, the historic ancient St. Alcmund’s Church was sadly pulled down for good despite the protests of residents. Thus the holy memory of this glorious saint was desecrated in peacetime, when there were neither Church reforms nor direct persecutions. The church was never restored, though a plaque in its memory was erected nearby.

However, the saint did not leave believers without new miracles. When the church was demolished, a very ancient Saxon-era stone sarcophagus along with remnants of an early St. Alcmund’s high cross with carvings on its sides were revealed and discovered beneath it. This magnificent, elegant sarcophagus with interlaced designs was most certainly connected with Alcmund; and, according to some researchers, it may have been his original coffin. Now all these and some other relics and artefacts associated with our saint are kept in the Derby Museum and Art Gallery, which is visited not only by tourists, but also by pilgrims.

Derby has its own Anglican cathedral dedicated to All Saints—a large medieval church that obtained cathedral status only in the twentieth century. Alas, our self-sacrificing saint is not venerated in it either. As a small “compensation” for all of this, a modern Anglican church in honor of St. Alcmund was built in the 1970s in another district of this large industrial city. Notwithstanding all the ironies of history, the Passion-Bearer Alcmund is venerated as the heavenly patron of Derby to this day. Surprisingly, a very ancient holy well of St. Alcmund survives in this huge and busy metropolis. Formerly, numerous healing miracles were attributed to its waters. This well is several minutes’ walk from the site of the former St. Alcmund’s Church. The source of the well still flows; it has undergone some restoration work in recent years, and believers are warned against drinking its water today.

Derbyshire is famous for its old Christian tradition of “well-dressing”—decoration of wells, springs and other water sources on special days of the year with designs made of flowers, leaves, petals and other natural objects. The tradition has been revived in this rural heart of England over the past decades, and the number of towns that practice it has doubled. As for Alcmund’s well in Derby, the tradition of dressing it resumed in the 1870s and thrived until the 1990s when it again faded due to frequent cases of vandalism. The well itself, according to tradition, appeared through the prayers of St. Alcmund: When the procession with his relics was moving from Shrewsbury to Derby, its participants stopped here for a short rest, and a spring immediately gushed forth to slake the travelers’ thirst. The place has been considered holy since then. In the Middle Ages pilgrims coming to Derby would first stop at this well to have a sip of the water and ask for St. Alcmund’s blessing, and then they would proceed to his major church. It can be added that the local busy street of Derby was named “St. Alcmund’s Way” not long ago—a very poor form of atonement before the saint.

There is a southern residential suburb (formerly a peaceful village) of Duffield near Derby. It was here that the procession carrying Alcmund’s relics made another stop en route. A chapel in honor of St. Alcmund was erected in memory of this event. Though the chapel is long gone, there is still an active fourteenth-century parish church of St. Alcmund in this settlement, on the bank of the River Derwent.

Our saint is venerated outside Derby, too. In Shropshire, churches in the towns of Shrewsbury and Whitchurch are dedicated to Alcmund. St. Alcmund’s is one of a number of historic churches of Shrewsbury—one of the finest towns of England. The first church was built in 912, and since then replacement churches have always stood on the highest point of the town where the Saxon market used to be held.

The prominent spire of St. Alcmund’s dates back to the fifteenth century. It is fifty-six meters (183.7 feet) tall, and together with some other buildings creates the unique skyline of the town, which was praised by the local poet Alfred Housman (1859-1936). After the collapse of the historic St. Chad’s Church of Shrewsbury in 1788, the local parishioners took fright and decided to rebuild St. Alcmund’s too, except for its tower and spire. So the present splendid church in the pseudo-Gothic style is just over 200 years old. It houses a set of famous historic stained glass windows and has a welcoming atmosphere. The town of Whitchurch derives its name from the white stone of the early church of St. Alcmund. The first church on this site dates back to 912. The medieval structure stood for many years, but after the collapse of its tower the whole building was rebuilt in 1713.

Outside these two counties, churches dedicated to Alcmund can be found in Aymestrey (north-west Herefordshire, just to the south of Shropshire; the other church patron is St. John the Baptist) and Blyborough (in Lincolnshire). It is obvious that all these Mercian dedications first appeared in the early tenth century through the efforts of Aelthelflaed, Lady of Mercia (870-918; the elder daughter of St. Alfred the Great), who for some time ruled Mercia, and promoted and venerated saints—all the more so because the two Shropshire churches and the Herefordshire church form a line between Gloucester and Chester and were built in fortified towns.

Finally, the village of Lilleshall, the first resting-place of Alcmund, still exists, sitting between the Shropshire towns of Telford and Newport. This place is holy. It has two ancient shrines and is closely associated with two early saints. The shrines in question are the Norman Church of Archangel Michael and All Angels in the very village, and the well-preserved ruins of the Augustinian Abbey, which was founded in 1148 just outside the settlement. The two saints in question are St. Alcmund, whose remains rested here from the year 800, and St. Chad, Apostle of the Mercians, who preached in this settlement, baptized its population and erected the first church. However, it is not known for certain where exactly in this village stood the first church, built by Chad, and where exactly Alcmund’s relics lay. It would be logical to suggest that it was on the site or beside the present Norman church.

In art, our saint is depicted as a prince or a king (he may have briefly ruled Northumbria following his return from Scotland) with a crown or a sword. Alcmund the Passion-Bearer should be distinguished from another saint with the same name: Holy Hierarch Alcmund, the seventh bishop of Hexham in Northumbria, who reposed in 781 and is commemorated on September 7/20.

Holy Hermit Bertram of Ilam and Holy Passion-Bearer Alcmund, pray to God for us!