What is solitude? Perhaps it is when we do not open up our soul to other people. Or, on the contrary, it comes when we feel strongly that our soul is not needed by anybody. Sometimes both these possibilities may merge.

Or maybe it is just the awareness of our being? “I am”, and all we really know by our own experience is that we exist. “I exist. And existentially, in principle, I am alone.” This is what the French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus would have said. But an answer like this lacks something. To put it better, it lacks somebody.

We are continuing the search for an answer.

***

Solitude (loneliness) is suffering. Indeed, in solitude you find yourself face-to-face with your pain. And most people in the world will surely put solitude on the same level with suffering.

However there were people in our history who always sought solitude themselves. There were many such writers, painters and musicians. They fled the world in order to give it the fruits of their solitude afterwards. The great music that we admire and call “the work of a genius”; the paintings that attract millions of people; the books which amaze us with the profundity of thought—all these masterpieces come into being through creative solitude which is always accompanied by inward suffering of their authors.

Men of genius are those who seek isolation and suffer from it at the same time. All the others suffer from isolation too yet try to avoid it.

***

The human soul naturally wishes to open up to somebody else, to “share itself” and to be nurtured by another soul. But if we allow somebody to get too close to us, we start feeling uncomfortable because of an intrusion into “the holy of holies” (that is, our hearts) along with an inevitable sense of bitterness and misunderstanding.

This situation was described by the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) in his famous porcupine dilemma (also known as the hedgehog’s dilemma). When a group of these animals feel cold, they move close to one another to get warm, but soon they hurt each other with their sharp quills and so pull away. However, they begin to feel cold again and huddle together, this time finding a tolerable distance between them to avoid prickling each other. Likewise, people are brought closer together by the void in their hearts, and, hurting one another, they start to drift apart—but only to come together again, once loneliness becomes unbearable. Courtesy and the conventional norms of conduct are nothing but a “safe distance” from our solitude.

As a matter of fact, a huge number of “knock-down” aphorisms belong to Schopenhauer that are as true as they are sad. For example, “The social impulse does not rest directly upon the love of society, but upon the fear of solitude”1, or “A man can be himself only so long as he is alone”2.

Interestingly, with the development of megalopolises the odd phenomenon of “urban loneliness” became widespread. It appears that the larger the crowd bustling around you, the sharper the blade of the loneliness that pierces your heart. Why so? It is because you realize that all of them live their own lives and not your life. A huge number of “not-yous”, who aren’t the least bit interested in you, disturb your peace of mind in proportion to their quantity. The more “not-yous” surrounding you, the more lonely you feel.

But if there is someone in this faceless crowd who is thinking of you and looking forward to meeting with you, then you don’t feel unwanted and abandoned any more. However, somebody’s love is like a drug addiction. The more you use it the more you are dependent on it. And, on the other hand, you get used to this love and appreciate it less. You can overcome depression and loneliness only when you learn to love others and to be totally devoted to them. It was, is and will always be so. Any psychologist can tell you dozens of stories of how people were healed from inner crises through their service to others. And, true, at the Last Judgment we will be asked how we loved our neighbors, not how our neighbors loved us!

***

Solitude may become a school of self-knowledge and knowledge of God for those who like learning and are inclined to contemplation. If a person shuts himself off from the world and minimizes his contacts with others, then there are three possible outcomes:

-

He finds solitude unbearable and returns to the world;

-

He goes mad;

-

An intensive inner work in his soul begins.

In connection with this I recall a fine short story, “The Bet” by the Russian author Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (1860-1904). A wealthy banker and a poor young lawyer made a bet: If the lawyer would spend fifteen years in solitary confinement, then the banker would give him two million rubles. Thus, taking up his residence in an outbuilding in the banker’s garden, the young man went through three stages of development. During the first year of his voluntary confinement the lawyer felt lonely, read novels and detective stories, and played the piano. During the second year the music stopped and the man asked for volumes of classical literature to be brought to him. In the fifth year the recluse asked for wine and began to play the piano again; he read no books during that period. In the sixth year the lawyer decided to learn foreign languages very energetically, together with philosophy and history. When the first ten years had elapsed, the wise man would read only one book day and night—the Gospel. After that he demanded that books on theology and history of religions be given to him. Then the recluse spent the final two years of his isolation reading all sorts of books indiscriminately. Five hours before his time was up he left his place of confinement and thus broke off the bet. He left a note where he explained that he didn’t need that money any more. The years of solitude spent in self-education and self-knowledge brought him close to God and helped him find the purpose of life.

And here is an example from the real life of a real and famous person—the last leader of the Zaporozhian Sech [a semi-autonomous polity in a region of what is now Ukraine that existed from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries] Petro Kalmyshevsky. When the Sech was abolished, the eighty-five-year-old Cossack was sent to prison in Solovki Monastery where he was to spend twenty-five years absolutely alone in a small one-man confinement cell. The prisoner was let out only three times a year: on the feasts of Nativity, Pascha and Transfiguration (the monastery’s patronal feast). When the Cossack was finally pardoned at the age of 110 he decided not to return to Ukraine and remained at the monastery. Kalmyshevsky lived for about three more years on Solovki, spending almost all his time in prayer, until his death. Now he is locally venerated as a saint in the Diocese of Zaporizhzhya (UOC-MP).

“A personality develops in solitude, in cold emptiness, where it becomes clear to a man that he is born alone and dies alone. In this emptiness he begins to pray. And then God fills this emptiness. The man begins to grasp his past life and eternity becomes evident,” writes a modern pastor Archpriest Andrei Tkachev3.

Solitude shows us who we are and gives us an opportunity to fill the “yawning abyss” of the human soul. Whether this vacuum is to be filled by God, or the “babble and rattle” of TV, or the escape from ourselves into the labyrinths of social media—the choice is in our hands. Our history knows examples that help us make a right decision.

***

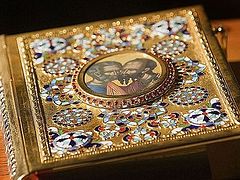

There is also a special kind of solitude—monasticism. In some sense, the words “solitude” and “monasticism” are related. The very word “monasticism” comes from the Greek “monos” meaning “alone”. This kind of voluntary solitude is also defined by the words: “I and God”, or rather, “God and I”. If monasticism is about this, then it is the only and genuine justification of solitude. But can a layman reflect on monasticism? It is like a splendid yet closed casket with a gem in it. You can only admire it, but you cannot “touch” and understand it as a layperson.

Meanwhile, St. Ignatius Brianchaninov wrote about “monks in tailcoats”, that is, laymen who lived according to the Gospel and knew about mental prayer and other podvigs [spiritual labors] not only from books, but also from their personal experience. St. Theophan the Recluse expressed very similar thoughts. The saint himself used to send letters from his seclusion addressed to a certain landowner, a layman, asking his advice concerning contemplative prayer. Later a remarkable preacher and pastor Archpriest Valentin Sventsitsky (1882-1931) developed the theme of “monks in tailcoats” into his own idea of a “monastery in the world”. Therefore, solitude filled by God is an ideal which can be achieved not only at a monastery, but also outside it. When the Lord comes to man, the latter is no longer alone.

***

We will never be able to avoid solitude completely, but we surely can find God in it, come out of our shell and move towards people. And most likely there is no other solution to this problem.

Do you want to free yourself from the solitude that has been tormenting you for years? Become everything at the very least for one person in the world. Serve him who needs your support. Try to understand that you can become happy by being useful to others.

A hospital, a prison, a nursing home, a children’s home—these are some of the places that will help you pass from words (and philosophizing) to deeds. In these institutions, solitude acquires new qualities. In any case, you will not be despondent and depressed any more as you will have no more time for sadness.

***

Solitude is inescapable. It is a constant companion of every individual in his life’s path. Loneliness is a common human experience and the normal feeling of a sinner who has fallen away from his Creator. Once a small branch has broken off the grapevine, it always feels its deficiency and littleness. Whether you are happy or completely unhappy in your life on earth, you will inevitably experience your natural solitude in the ontological sense as a personal uniqueness and personal pain until your death—the above-mentioned “I am”, “I exist”. The abyss of soul designed for the eternal God keeps reminding us of itself. Deep calleth unto deep at the noise of thy waterspouts (Ps. 42:7 according to KJV).

Solitude is vital. It gives self-knowledge and exposes the age-old pain of Adam who sinned and is still hiding from his Lord in the bushes of his loneliness. But we should come out of the bushes towards God and His creation. Yes, walking this path is maybe more painful than sitting in Adam’s bushes. But on this path the abyss of our soul will find Him Who can fill it and will meet those who have similar abysses. “Call upon the Creator from the abyss of your heart, and He will fill your ‘limited infinity’”—this is what solitude tells us.

It is for this meeting that the incessant voice of solitude sounds within us, and it is the purpose of our life on earth.