St. Rumwold (other forms of his name are Rumwald, Rumbold, Rumbald, Rumoalde) is a mystery-saint and a true wonder. In world Orthodox hagiography there are numerous examples of saints (not least in Russian hagiography) who were children and adolescents and have been greatly venerated over the centuries. But hardly any newly-born babies, who lived only for a few days (and were not martyred), are venerated as saints by the Church. One of these unique saints is the holy prince and infant Rumwold who lived in seventh-century England. Not only was Rumwold recognized as a saint, thanks to him many inhabitants of early and late medieval England came to believe in Christ, and his popular veneration was nearly nationwide. Nowadays this marvelous infant-saint is venerated by Anglicans, Catholics and Orthodox, including Russian Orthodox believers living in the UK. Let us recall his story.

Unfortunately, very few facts of St. Rumwold’s extremely short life survive. Though his name was included in some early English calendars, his first Life was composed in the scriptorium of Worcester monastery-cathedral in the eleventh century, that is, some 400 years after his death. Further in the Middle Ages new versions of his Life were composed which, however, are not very reliable. Nevertheless, all these hagiographies, coupled with oral traditions of pious Christians, are based on facts. The narrator of the medieval account of St. Rumwold’s story makes one serious mistake, saying that the saint’s parents came from pagan Northumbria and Christian Mercia respectively, whereas in reality it was the other way round. Our saint was born in about 650-653 (some sources give 662), when the kingdom of Northumbria in the north (at times divided into Deira and Bernicia) was already Orthodox, and Mercia in the center was still largely pagan, ruled for about thirty years by the ferocious King Penda.

No author gives the names of Rumwold’s parents but there is an indication that they were a Northumbrian prince and a Mercian princess. These marriages between members of royal families of early English kingdoms were widespread in that age and contributed to the establishment of Christianity and friendly relations. Most probably the holy infant was a son of either King Ethelwald of Deira (ruled 651-655, a son of the holy king-martyr Oswald) and one of King Penda’s daughters who was converted to Orthodoxy; or of King Alhfrith of Deira (ruled 655-664) and the holy Princess Cyneburgh—one of Penda’s daughters (who later became a nun, founded the double monastery in Castor in what is now Cambridgeshire, served as its abbess, and after her repose in about 680 was numbered among the saints and is still venerated locally).

The font in which St. Rumwold is believed to have been baptized, the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Kings Sutton, Northants (used by the kind permission of the Kings Sutton vicar)

The font in which St. Rumwold is believed to have been baptized, the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Kings Sutton, Northants (used by the kind permission of the Kings Sutton vicar) Whatever is the truth concerning the identity of Rumwold’s parents, what is certain is that he was born on their way from Northumbria to the royal residence in Mercia. The parents were probably going to visit King Penda himself. His mother was in labor when they were already in Mercia, so the royal couple had to stop en route in what is now the village of Kings Sutton—on the border of the counties Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire. It was there that the mother gave birth to Rumwold in a hastily erected tent. For some reason they had their infant immediately baptized—maybe for the fear of the baby’s ill health. It was done in a miraculously discovered bowl-shaped boulder. After that Rumwold was chrismated and given communion by priests named Widerin and Edwold. On the third day of his life the infant reposed. However, an extraordinary miracle occurred in his extremely short life. The holy infant began to speak!

At the very least, according to all the ancient sources and traditions, Rumwold exclaimed several times in a loud voice: “I am a Christian!” Later medieval authors give legendary accounts, adding that the boy within these three days also made a profession of the faith in the Triune God; asked for baptism and then—for Holy Communion; asked to give him the name “Rumwold”; preached an eloquent sermon on the Holy Trinity and the need for a devout Christian life; freely cited the Bible and the Athanasian Creed; predicted his imminent demise; and made directions regarding his burial—namely he asked to be buried first at Kings Sutton (then simply “Sutton”) for a year, next at the neighboring settlement of Brackley in what is now Northamptonshire, and, finally, in Buckingham (in Buckinghamshire)—forever. All of this was done according to his command. We may believe these details or not, but the mere fact that the infant began to speak and called himself a Christian demonstrates that he was filled with the grace of God and was Christ’s chosen one. And these words—“I am a Christian!” proved to be real preaching, a real “missionary act” for many generations. We can only marvel at the mysterious ways of God in the example with this saint.

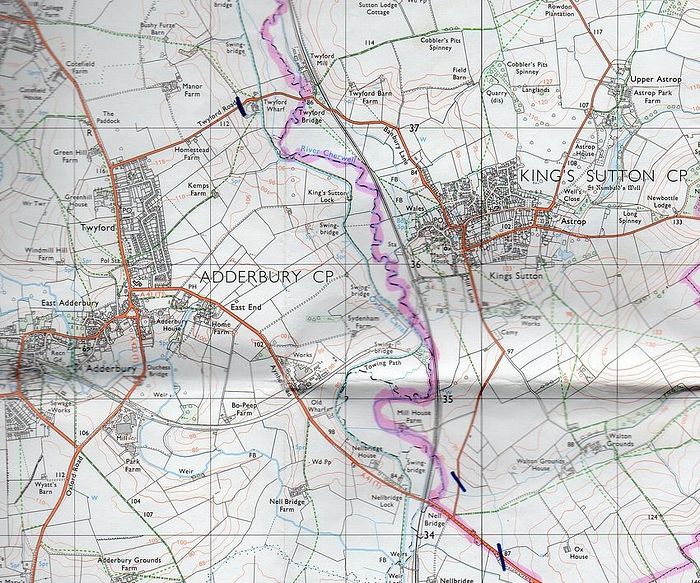

An older ordnance survey map of Kings Sutton and surroundings where St. Rumwold's well was still indicated (the image provided by the vicar of Kings Sutton)

An older ordnance survey map of Kings Sutton and surroundings where St. Rumwold's well was still indicated (the image provided by the vicar of Kings Sutton) On the third day after Rumwold’s death his parents buried him at Kings Sutton and erected a chapel above his grave. Afterwards holy wells with healing properties appeared in all three places of his burial in succession—Kings Sutton, Brackley and Buckingham. However, it was at Buckingham that his holy relics remained forever and were visited and venerated by thousands of pilgrims permanently until the Reformation. The relics of Rumwold were a source of numerous wonderful miracles. People used to come to the holy infant and ask for his intercessions: women (and couples) asked him for their success in labor, for the health and well-being of their children; they asked him to guide and help their children become genuine Christians. Women who experienced miscarriages sought consolation at his shrine, and those who killed their babies sincerely repented and asked for the Lord’s forgiveness. Even in our own times, some Orthodox believers venerate St. Rumwold as the patron saint of the millions of unborn children who were and are still killed by means of abortions. Some Orthodox in English-speaking countries and even Russia pray to St. Rumwold for their children.

Eventually the veneration of Rumwold spread to many regions outside Northamptonshire and Buckinghamshire, reaching Kent, Essex and Lincolnshire in the south-east and east, Dorset in the south-west, North Yorkshire and Durham in the north. Churches were dedicated to our saint in all these counties, and some of them still survive. English people, especially the common folk, were inspired by the story and example of St. Rumwold and their faith increased thanks to the witness of this little holy infant. And this continued for many generations in succession. His veneration was so great that a number of pre-Conquest monasteries in the English kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex bore his name, and his statue was preserved at the Catholic monastery of Boxley in Kent until the Reformation. There is evidence that the veneration of Rumwold even reached mainland Europe, where he was commemorated in Sweden and other countries. Due to his close link with Buckingham and the presence of his relics there, this saint became known as “St. Rumwold of Buckingham”.

It is also noteworthy that the merit of Rumwold’s widespread veneration and popularity across England partly belongs to St. Wilfrid, Bishop of Hexham and York and a great missionary. Over his some fifty years of missionary activities Wilfrid travelled much in the north, center and south of England and may easily have spread the information on the unique St. Rumwold who had lived shortly before him.

As a result of all this, a number of towns and villages in England were named after St. Rumwold; streets in a number of English towns bear the name “St. Rumbold’s Street” to this day (among them are Lincoln and Buckingham); the towns of Shaftesbury in Dorset and Wallingford in Oxfordshire have a “St. Rumbold’s Road”; there is a “Rumbold Lane” in Wainfleet in Skegness, Lincolnshire; and in some regions of south England “Rumwold” and its variations are still widespread surnames. This celebrated saint was one of the heavenly patrons of the seaside Kent town of Folkestone, and his name was invoked by local fishermen until relatively recently.

The veneration of Rumwold in Buckingham—the main center—continued until the Reformation, when the veneration of saints officially ceased. His shrine was either destroyed or hidden within the town church which was dedicated to the holy Apostles Peter and Paul. The church itself literally collapsed in the 1770s due to its age, and a replacement church was built by 1780 nearby on the top of a hill called Castle Hill. The magnificent new church which stands there to this day is dedicated to Sts. Peter and Paul, like the original. Only some pews and other minor artefacts from the original church survive and are kept at the new one. However, the memory of the town’s patron-saint lives on in Buckingham. A memorial was recently erected in the old churchyard a few steps away from the current church marking the approximate site of the saint’s shrine. A plaque on the memorial reads: “Near this spot within the old church of Buckingham was the tomb and shrine of the infant saint Rumbold, who lived and died c. 650 A.D.”. A depiction of the holy infant is carved in the form of a cherub (one of his emblems) on a wall of the Old Manor Elizabethan-era building of Buckingham.

The Old Gaol Museum in Buckingham, which was formerly a prison, has a section dedicated to St. Rumwold and his well. An association to promote information about him and to preserve his memory and sites associated with him, called The St. Rumwold Group, was set up in Buckinghamshire several years ago. The ancient holy well of St. Rumwold just to the south-west of Buckingham near the disused railway line, that used to heal blindness and many other diseases in the past, only partly survives. There were attempts to restore its stone structure at the beginning of this century but due to repeated acts of vandalism it is in a rather ruinous condition today and dry most of the year. However, the site is now a scheduled monument. Rumwold is portrayed on the metal plaque at the well’s gate as a cherub. Remains of the old conduit house attached to the well were found during the restoration work and are preserved.

The town of Buckingham itself (the name meaning “Meadow of the people of Bucca”) is quaint. It stands in north Buckinghamshire near the River Great Ouse and has a population of about 12,000 people. It was the county town of Buckinghamshire from the tenth till the eighteenth century, when Aylesbury took over this role. Notably, the great and prolific English Gothic Revival architect Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878) who, among other things, restored many English churches and cathedrals, was born in the village of Gawcott just one and a half miles from Buckingham.

The village of Kings Sutton in south Northamptonshire, situated in the valley of the River Cherwell twelve miles west of Buckingham and near the picturesque town of Banbury (in neighboring Oxfordshire), is still visited by Orthodox and other pilgrims as the birthplace of the holy infant. Its name means “the King’s South Estate”. The exact place of his birth is in Walton on the village outskirts which is now a field. The village parish church is dedicated to the holy apostles Peter and Paul. Its main treasure is the huge late Saxon or early Norman font. Perhaps the present font incorporates the original structure where the infant-saint was baptized, but it was enlarged with time. This relic was discovered in the 1920s underneath a mound in the churchyard. The local parish commemorates the holy infant every year with a mass on November 3 (his feast-day according to the old calendar). The church sticks to the “High Church” tradition of Anglicanism.

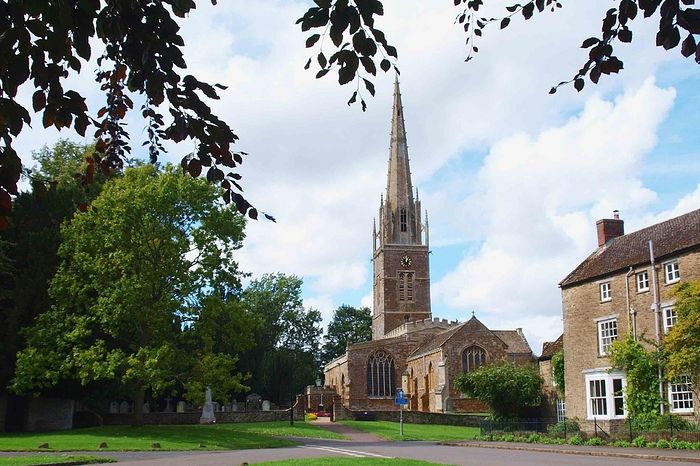

The Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Kings Sutton, Northants (photo used with the kind permission of the vicar of Kings Sutton)

The Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Kings Sutton, Northants (photo used with the kind permission of the vicar of Kings Sutton) The earliest part of the Sts. Peter and Paul’s Church is its Norman chancel. The present building was constructed between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. Several parts of it are medieval and are Decorated Gothic and Perpendicular Gothic in style. It boasts a number of fine stained glass windows and other artworks inside. Its other gem is its ancient tower with its high spire which makes the whole steeple 198 feet tall. In general, the county of Northamptonshire is famous for its churches with tall towers and spires. This unique feature was observed by the great expert Sir Nikolaus Pevsner (1902–1983)—a German-born British art historian, best known for The Buildings of England, a county-by-county guide to British architecture in 46 volumes. Pevsner referred to the Kings Sutton’s spire as to “one of the finest in this county”.

Face on tower, the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Kings Sutton, Northants (photo used with the kind permission of the vicar of Kings Sutton)

Face on tower, the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Kings Sutton, Northants (photo used with the kind permission of the vicar of Kings Sutton)

The St. Rumwold’s holy well near Kings Sutton, situated in the spot called Astrop, still survives. It had been in neglect for some time until it was rediscovered in the eighteenth century when a sort of a “spa” was set up there which enjoyed huge popularity. It was in the grounds of the large house called Astrop House. However, in the 1860s this well was abandoned (now it is on a private land and is difficult of access) and its source piped close to the road. The “replacement” holy well still exists, though for most of the time it is dry. The village of Kings Sutton is also famous for its ample musical and literary links.

The following Anglican parish churches are currently dedicated to St. Rumwold the Infant in England: a fourteenth-century church half a mile from the tiny hamlet of Bonnington in Kent, standing on the banks of the Royal Military Canal; a nineteenth-century parish church in the small Dorset village of Pentridge where, notably, direct ancestors of the poet Robert Browning (1812-1889) are commemorated; a Norman church in the village of Romaldkirk (“Rumwold’s Church”) in county Durham—nicknamed “the Cathedral of the Dales” - whose walls preserve some sections of the pre-Norman period and among whose relics are a twelfth-century font and a series of fourteenth-century windows; a church dating to 1725 in the Northamptonshire village of Stoke Doyle near the picturesque town of Oundle and close to the River Nene (the original church was pre-Norman); a thirteenth-century church in the hamlet of Strixton in Northamptonshire which preserves a fifteenth-century screen and other artefacts. The former Church of St. Rumwold in the beautiful city of Lincoln is now used as a college. In the 2000s it erected a monument to commemorate its patron-saint.

St. Rumwold of Buckingham should be distinguished from another saint with the same name (Rumbold or Rumoldus), an English missionary in Brabant and Holland and martyr who lived a century later (+ c. 775; feast: June 24) and to whom the ancient Catholic cathedral in the Belgian city of Mechelen is dedicated. In art St. Rumwold is depicted as an angel, as a preaching new-born infant-saint or in the midst of his miracle. An Orthodox service to St. Rumwold in English was composed at the beginning of this century.

Holy Infant Rumwold, pray to God for us!