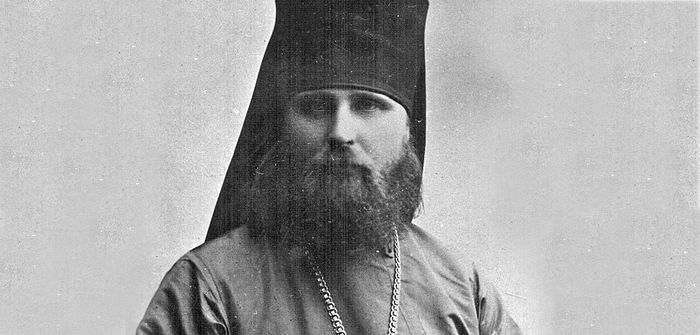

In honor of today's celebration of the centenary of the enthronement of St. Tikhon (Bellavin) as the first occupant of the renewed Russian patriarchal throne, we offer here the speech of Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitksy), given October 23, 1917 at the Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, in which he passionately argued for the restoration of the patriarchate to the Russian Orthodox Church, detailing the history and development of Church administration to make his case. As we know, the Council did decide to restore the patriarchate and elected St. Tikhon, who was enthroned this day in 1917 in the Dormition Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin.

Your Holiness, archpastors of the Russian Church, fathers and brothers!

We have already heard many speeches about the patriarchate. The majority of those who have spoken about the patriarchate here—both for and against—examined it from the point of view of its practicality and timeliness. Some laid upon the patriarchate perhaps exaggerated hopes of an ecclesiastical and even political character; others made haste to predict nearly complete disappointment for those who placed their hope upon the patriarchate. In the speeches, from either side, one and the same note was heard: Whether or not to restore the patriarchate depends upon what is more useful and more modern. For me, the question of the restoration of the patriarchate is completely different. We cannot not restore the patriarchate; we absolutely must restore it, because the patriarchate is the foundational law of the highest administration of every Local Church. This truth about the patriarchate is the foundation of my speech.

We have gathered here not to start a revolution in the Russian Orthodox Church. Our purpose is to free our Church administration from those wounds which appeared as the sad fruit of two centuries of captivity of the Russian Church by the state authorities. These wounds of our Church administration consist in its departure from strict compliance with the canonical system. This isn’t the Church of God’s first year on earth. Throughout entire centuries of its history, it established canonical norms for the higher administration of the Local Churches, and these norms were realized in defined Church law. We must understand the Church consciousness according to Church law and Church history, and determine what this Church consciousness demands of the higher administration of a Local Church.

The patriarchate had various forms in history; its historical forms changed depending upon conditions, place, and time. The higher administration of the Local Churches has also varied in its details, and Church law does not demand complete unanimity in this matter. But through all these historical variations, one immutable foundational rule has been preserved: At the head of the higher administration of every Local Church stands the first hierarch. This is the basic idea of the patriarchate. Let’s forget all the historical forms for a minute and ask: “What is a patriarchate?” It is, in essence, the leadership of the bishops of a Local Church by the first hierarch. This provision is the foundational principle of higher administration of every Local Church. We have heard confusion here: We don’t know what kind and with what authority the patriarch will be, and therefore we cannot yet desire the restoration of the patriarchate. To this confusion I answer: The patriarch will be how this Council makes him, and he will have the authority that the Council gives him. In this we are free; in defining the details of patriarchal administration we are free; but we cannot not restore the patriarchate—we have no right to this, if we do not want the suspect praise of the determined reformers of the Church, if we do not want to break with the age-old Tradition of the universal Church of Christ.

At the last meeting, Archpriest N. P. Dobronravov[1] said that the canons don’t say anything about the patriarchate. Prof. Titlinov[2] went further and declared that the idea of the patriarchal singular leadership is alien to the Orthodox Eastern Byzantine Tradition. When I heard these declarations, I must confess, my eyes opened wide with astonishment and bewilderment. So what is actually the Orthodox Church Tradition on the higher administration of Local Churches? Let us turn to history and the Church canons.

If we turn our minds to the earliest times in the historical life of the Church for the organization of the higher administration of Local Churches, we will find nothing. Why? Because there weren’t Local Churches yet then. Scattered throughout the whole world, the Churches, the dioceses and parishes are always located, of course, in close communion with one another, but in the first times they were independent in terms of administration, and not united in Local Churches of any defined ecclesial-administrative organization. Therefore, in vain we would look in the first two centuries for a defined model for the organization of the higher administration of the Local Russian Church. There is no such model. If someone decided now to restore the Church administration of the first two centuries, then he should demand the destruction of any higher Local Church administration and the provision of full independence for every diocese, headed by a bishop.

But it wasn’t long that the Local Churches of the Church of Christ went on without any organization. Christians, living in this or that province of the Roman Empire and thus or otherwise united in civil relations, of course, soon united in an ecclesial relation around the main city of the province—the metropolis. This process of organizing the Local Churches by provinces undoubtedly began already in the second century, and in the third century this process had already led to the formation of definite provincial Metropolitan Churches. This order of administration of these Local Churches had already unfolded, and for the First Ecumenical Council it was already “an ancient custom.” “Let the ancient customs in Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also. Likewise, in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges.”[3] Apostolic Canon 34 speaks of the administration of these ancient, first Local Churches. “The bishops of every nation (apparently people, living in this or that province, as the division of the Roman Empire into provinces had, among other things, an ethnographic foundation) must acknowledge him who is first among them and account him as their head, and do nothing of consequence without his consent; but each may do those things only which concern his own parish, and the country places which belong to it. But neither let him (who is the first) do anything without the consent of all; for so there will be unanimity, and God will be glorified through the Lord in the Holy Spirit.” Here are identified two principles of the higher administration of a Local Church: the council and the primate. Both councils and first hierarchs of Local Churches received a beginning already in the second century. Councils do not exclude the first hierarch, nor vice versa. On the contrary, according to the apostolic rule, a combination of the first hierarch and the council of a Local Church dictate Church unity, and in this unity is found the glorification of the All-Holy Trinity.

There is a whole series of canons for the administration of Local Metropolitan Churches defined by the councils of the fourth century: of Antioch (canons 16-20, and 9), and Sardica (Canon 14). All of these canons establish that at the head of the administration of a Local Church stands the synod and the metropolitan, with the particular rights belonging to him as the first hierarch. No one then thought the existence of a first hierarch was contrary to the principle of catholicity. On the contrary, the leading of a Local Church by the first hierarch-metropolitan was considered a necessary addition and the perfection of the catholicity of administration. In the canons of the Council of Antioch (16-18) there is the concept of a “full synod.” What is a “full synod?” “And that shall be [accounted] a full synod, in which the metropolitan is present,” answers canon 16 of the Council of Antioch. Thus, we see that in distant centuries, as soon as the first Local Churches began to form, they were headed by a first hierarch-metropolitan named for the main cities of the provinces-metropolises.

The organization of the Church did not end with the metropolitan Local Churches. It continued in accordance with the administrative divisions of the Roman Empire. The empire had large administrative regions—dioceses. The Local Churches, located within the same diocese, soon joined together so that the Church of the entire diocese became a Local Church. As soon as the union of the Churches of a diocese was completed, a new type of first hierarch was immediately established at the head of each Local Church over all the metropolitans. The Second Ecumenical Council speaks of such Local Churches in canons 2 and 6, calling first hierarchs bishops of a diocese and defining the limits of their Church realms. The Fourth Ecumenical Council calls the same first hierarchs exarchs of a diocese (canons 9 and 17), but the bishop of Constantinople is called an archbishop (canon 28).

Thus, with the new form of Local Churches, an unchanging law of the leadership of their higher administration by a first hierarch is preserved.

The next level of Church organization is the patriarchates, which were formed from the union of several dioceses in an ecclesiastical relationship. Thus, the Thracian, Asian, and Pontian Dioceses made up the Patriarchate of Constantinople. At the head of the patriarchates, of these Local Churches of the latest type, are the patriarchs. The Byzantine Empire never coincided with one Local Church; there were several separate Churches with patriarchs at the head within its boundaries. Afterwards, the Local Churches were created on the principle of, among other things, nationality. In moments of a rise of national strength and identity, people would organize for themselves an autocephalous Church and it would be headed by a first hierarch. So it went, for example, in Serbia in the fourteenth century under Stefan Dušan, when the autocephaly of the Serbian Church was declared and the Serbian patriarch was installed.

Our Russian Church was started as a metropolitanate of the Patriarchate of Constantinople; it became autocephalous from the middle of the fifteenth century, under the leadership of the metropolitan of Moscow, and became a patriarchate in 1589. At present, the Orthodox Church consists of sixteen autocephalous Churches, and all of these Churches—Greek, Slavic, Arabic, Romanian—have a first hierarch at the head—with various titles and various authority, but they all have first hierarchs. It is the same with the communities that have fallen away from the Church, such as the Armenians, the Jacobites, and others.

Such is the witness of history. The forms of higher administration of the Local Churches change everywhere and always, the Local Churches themselves change, but the law of higher administration according to which they are headed by a first hierarch is preserved unchanged. The names and scope of power of the first hierarch varies, but the principle of a first hierarch in every Local Church is steadfast.

Our poor Russian Church with its synod is an unfortunate exception. The entire ecumenical Church of Christ before 1721 did not know a single Local Church managed collegially, without a first hierarch. The Russian Church was never without a first hierarch. Our patriarchate was destroyed by Peter I. What was it obstructing? The catholicity of the Church? But weren’t there especially many councils during the time of the patriarchs? No, the catholicity and the Church were not obstructed by the patriarchate. So what was it hurting? We have before us two great friends, two beauties of the seventeenth century—Patriarch Nikon and Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. To split up the friends, evil boyars would whisper to the tsar: “Nobody sees you, Tsar, because of the patriarch.” And Nikon, when he left the Moscow throne, wrote, among other things, “Let him, the tsar, without me receive wider acclaim.” Peter realized this thought of Nikon, destroying the patriarchate. “Let me, the tsar, receive wider acclaim without the patriarch.” The Moscow monarchy, transformed by Peter into an unlimited autocracy, was encumbered by the Russian patriarchate. In collision with the state powers, the Russian patriarchate waned in time, and the head of the Russian Church became an unknown-in-the-whole-Christian-Church collegium, in which the spirit of the monarch soon reigned, because the hussars assigned to it by the ober-procurator “commanded the host of hierarchs as a squadron in training.” The institution of the collegium was, in any case, a novelty in the Church of Christ, and this novelty was created according to a Dutch-German example and was not at all for the good of the Church.

Let us now ask: What is this constant, always and everywhere unchanging phenomenon in the Church of Christ, that at the head of the administration of a Local Church is the first hierarch? Is it really some error of all the ages, all the Local Churches, which we have been called to fix? Has everyone really been in error, and the truth has been revealed to us alone? Have all the Local Churches, establishing the primacy of first hierarchs, pushed Christ away from themselves, desiring that Christ not be among them but rather the patriarch, as the work of the institution of the patriarchate was presented in one of our previous meetings by Archpriest N. V. Tsvetkov?[4] Isn’t this too much of a proud and arrogant attitude towards the Tradition of the whole universal Church of Christ? Would it not be better for us to humbly bow to the fundamental law of the higher administration of a Local Church, as clear as this law is from history and the canons?

We heard the objection from the mouth of Professor Titlinov at the last meeting that the patriarchate is a Western, Papist idea. Nothing of the sort. The papacy wants to rule over the entire Church, but a patriarch is the head of a Local Church. Does anyone here really want the Moscow patriarch to subdue all sixteen Local Churches under his authority? For us, the idea of Papism can have no ground in the modern Orthodox Church. On the other hand, the pope runs the Church single-handedly, sine consensus ecclesiae—without the consent of the Church—but the Orthodox first hierarch of a Local Church does nothing without the consideration of all its bishops. Inasmuch as the 34th Apostolic Canon authoritatively demands a patriarchate in every Local Church, so it denounces the delusion of the papists. Polemics with the Latins should use, among other things, the 34th Apostolic Canon. There are no papist-heretics among us, but there are many Orthodox patriarchy supporters. Papism and the patriarchal system have nothing in common, and every mention of papism at our Orthodox Council is completely superfluous and unnecessary. It’s not a papist tendency that demands the restoration of the patriarchate, but an Orthodox ecclesiastical consciousness.

Let’s turn to 1917. Apparently, we have not come to this Council at the right time to talk about the patriarchate. The Pre-Conciliar Committee answered the question about the patriarchate very quickly and decisively: The patriarchate contradicts the principle of conciliarity, and therefore it’s not worth it to restore it. “The All-Russian Church-Society Herald” has printed satirical articles against the patriarchate in nearly every issue. Even one of the synodal institutions (the Publishing Council) published an unscrupulous leaflet under the title “Do We Need a Patriarch?” The flyer answers the question negatively, and the last synod, created by the last ober-procurator, according to custom, silently “took note of” this inexcusable mockery of the sacred idea of the patriarchate. Finally, we are dominated by a “revolutionary” ochlocracy, which can always make a denunciation of the imaginary counter-revolutionary nature of the patriarchate. And what? Despite all that, we are speaking about the patriarchate. The first major question we are discussing is the question of the patriarchate. In this Department of Higher Administration, we cannot help but to speak about the patriarchate first of all. We have not refrained from it here, at this general gathering of our Synod. My heart already joyfully experiences the pre-feast of the great ecclesial-national celebration of the restoration of the patriarchate. Those who in our gatherings take exception to the patriarchate themselves admitted last time that they are taking upon themselves a thankless task and are giving hopeless speeches. But why? Where does this come from? Does it not mean that Church consciousness, both in the 34th Apostolic Canon, and in the 1917 Moscow Council, speaks invariably the same: “The bishops of every nation, including the Russian, must acknowledge him who is first among them and account him as their head.”

I would like to address all those who for some reason consider it yet necessary to oppose the patriarchate. Fathers and brothers! Do not destroy the joy of our oneness-of-mind! Why are you taking this thankless task upon yourselves? Why are you offering hopeless speeches? After all, you are struggling against the consciousness of the Church. Beware, that you don’t find yourselves fighting against God (cf. Acts 5:39)! We have already transgressed in that we did not restore the patriarchate two months ago when we came to Moscow for the first time and met with one another in the Great Dormition Cathedral. Was there really anyone then not wounded to tears to see the empty patriarchal seat? Was it truly not a shame to see how the Metropolitan of Moscow stood the entire Dormition Vigil somewhere under scaffolding? Was it not bitter to see some dirty plank on the historical patriarchal spot, and not a patriarch? And when we venerated the holy relics of the wonderworkers of Moscow and first hierarchs of Russia, did we not hear then their rebuke for leaving their primatial chair widowed for 200 years?

In Jerusalem there is the Wailing Wall. Old Orthodox Jews go up to it and cry, shedding tears for their lost national freedom and for their former national glory. In Moscow, in the Dormition Cathedral, there is also a Russian wailing wall—the empty patriarchal chair. For 200 years, Orthodox Russians have come here to weep bitter tears for the ecclesiastical freedom destroyed by Peter and for our former ecclesiastical glory. What misery it will be if from henceforth and forevermore it remains our Russian wailing wall! May it not be so!

Moscow is called the heart of Russia. But where in Moscow does the Russian heart beat? At the exchange house? At merchants’ row? At Kuznets Bridge? It beats, of course, in the Kremlin. But where in the Kremlin? In the district court? Or in the soldiers’ barracks? No, in Dormition Cathedral. There, at the front right pillar should beat the Russian Orthodox heart. Peter’s eagle, arranged in a Western style of autocracy, has pecked out this Russian Orthodox heart. The sacrilegious hand of the impious Peter brought the Russian first hierarch down from his centuries-old place in the Dormition Cathedral. The Local Council of the Russian Church, by the authority given it by God, will again place the Moscow patriarch on his lawful and inherent place. And when His Holiness the patriarch goes to his historical sacred place in Dormition Cathedral under the ringing of Moscow bells, there will be great joy both on Earth and in Heaven.

Originally printed in Russian as “Why Is It Necessary to Restore the Patriarchate? Speech at the October 23 General Meeting of the Church Council by Professor of the Moscow Theological Academy Archimandrite Hilarion” in Theological Herald (Bogoslovsky Vestnik), 1917. X-XII.

***

The question of the restoration of the patriarchate evoked the most heated discussion at the Local Council. Formed on April 29, 1917, the Pre-Conciliar Committee rejected the proposal to restore the patriarchate. At the Council itself, the question of the restoration of the patriarchate was reopened on October 11 by a report of the Chairman of the Department of Higher Church Administration Bishop Mitrophan (Krasnopolsky) of Astrakhan. The question caused a fierce debate, and ninety-five people immediately signed up to speak on the topic. Archimandrite Hilarion gave his talk “Why Is It Necessary to Restore the Patriarchate?” at the Council’s general session on October 23.

The controversy surrounding the restoration of the patriarchate hit the Moscow Theological Academy as well. Having heard about it, Archimandrite Hilarion left the Council and went to the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, where he gave a three-hour lecture before the teachers and students on the topic, “Is It Necessary to Restore the Patriarchate to the Russian Church?” “Now is coming a time,” he said, “when the patriarchal crown will be not a ‘royal’ crown, but rather the crown of a martyr and confessor, who will selflessly guide the ship of the Church in its navigating the turbulent waves of the sea of life.” The lecture was met with thunderous applause, showing that the majority of those present fully shared the thoughts of the presenter. After that, Archimandrite Hilarion returned to the Council.

The question of the restoration of the patriarchate was put to a vote on October 28, and that same day the Council rendered the decision to restore the patriarchate.