Depiction of St. Withburgh on the painted panel behind the High Altar of St. Nicholas Church, Dereham, Norfolk (kindly provided by the churchwarden of St. Nicholas Church)

Depiction of St. Withburgh on the painted panel behind the High Altar of St. Nicholas Church, Dereham, Norfolk (kindly provided by the churchwarden of St. Nicholas Church) St. Withburgh was the youngest daughter of the pious king Anna of East Anglia (ruled 635-653 or 654), who, according to tradition, had six holy children and was martyred by the pagan King Penda of Mercia. Although the Venerable Bede does not mention her, we know about St. Withburgh from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, early traditions and the Latin manuscript called Liber Eliensis (“the Book of Ely”), which is a chronicle compiled in the monastery in Ely at the beginning of the twelfth century and contains, among other things, brief Lives of several East Anglian female saints.

When Withburgh was a little girl, her father was murdered. Tradition holds that she was brought up by her nurse on her father’s estate in Holkham – a village on the north coast of Norfolk. The twelfth-century Life relates how Withburgh, who was educated there by her tutors, as a girl used to play with other children on the seashore. Once as they were playing, the young saint gathered up small pebbles mixed with sand in a pile, which miraculously began swelling until it turned into one solid mass. The saint made the sign of the cross, and the mass of pebbles and sand could not be scattered from that day on. The nurse then predicted that a holy church would be built on this spot, and this is exactly what happened. This story can be understood spiritually. A church was erected at Holkham in the eighth century on a man-made mound, dedicated to St. Withburgh, and its successor stands there to this day.

Withburgh led an austere ascetic life as an anchoress in Holkham for some years and in memory of her spiritual labors this place was renamed “Withburgstowe” (“the holy place of St. Withburgh”) for several centuries. Later she moved to the settlement, now called Dereham (formerly East Dereham) in central Norfolk where she remained for the rest of her life. The saint of God lived a holy life there and founded a convent, creating a community of nuns. It was written that by the time of her repose the nunnery building was not completed. From all appearances, the community arranged for the local population to be taught and cared for. Remarkably, the Mother of God appeared to Withburgh more than once during her solitary life. Thus she is in a very select company of early English saints who were found worthy of conversing with the Virgin Mary (another example is St. Egwin of Worcester, founder of Evesham Monastery).

It was related that at one time during building work the saint had nothing to feed her workers and nuns with except for dry bread. She began to pray fervently and the Mother of God appeared to her in a vision, commanding her to tell some sisters to go to a spring nearby. The next morning the sisters found two wild does (roe deer) there. The does let the sisters milk them and miraculously they provided plenty of milk. They would come to the same place every morning and were milked. So by miracle all the community and guests were supplied with milk for many years. The supplies of butter and cheese never ran out at the convent. Thus, Dereham is one of the holy places of England blessed by the appearance of the Mother of God. (It is less than fifteen miles away from the village of Walsingham, where, according to tradition, in 1061 the Mother of God appeared to a Norman noblewoman Richeldis de Faverches. This resulted in the foundation of one of the greatest shrines in England: a replica of the house of Nazareth, where the Archangel Gabriel brought Mary the Good Tidings that She was to become the Mother of the Savior of the world. A monastery and a wonderworking statue of Theotokos were also created there).

Depiction of St. Withburgh on the screen of St. Andrew's Church in Great Ryburgh, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Great Ryburgh church)

Depiction of St. Withburgh on the screen of St. Andrew's Church in Great Ryburgh, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Great Ryburgh church) Fifty-five years later, in 798, as was attested to by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the relics of Withburgh were exhumed and transferred to the same church. They were found incorrupt. Veneration for the saint grew and hundreds of believers from far and wide flocked to her shrine for healing and consolation. In the tenth century, England saw a period of revival of monastic life and piety. In that century Ely Monastery was reopened and the relics of St. Etheldreda (its founder in 673), her eldest sister St. Sexburga and niece St. Ermenilda (Ermengild) were eventually enshrined there. In 974, Brithnoth, Abbot of Ely, deemed it reasonable to move the relics of Etheldreda’s youngest sister Withburgh to Ely and place her body together with the former. According to tradition, this was done secretly at night and against the Dereham townsfolk’s will. They began to grieve their loss but on the same day a pure healing spring gushed forth in the former grave of St. Withburgh beside the church. It was regarded as a sign of consolation from the saint with whose bodily remains they had had to part. The holy well was dedicated to St. Withburgh and was for many centuries renowned for its curative properties, attracting crowds of pilgrims. Its waters have always remained pure and it has never run dry for the past 1,000 years regardless of the weather. And this miraculous well still exists.

In Ely (Cambridgeshire) veneration for St. Withburgh continued, though it never “eclipsed” that of Etheldreda. As was recorded in the Ely chronicles, the relics of St. Withburgh were opened in 1102 and moved to a new site within the Ely church, and four years later they were translated into the new church (now the huge Ely Cathedral) together with the relics of Sts. Etheldreda and other local saints. And whereas it was found that the relics of Sts. Sexburga and Ermenilda had been reduced to bones by that time, the relics of St. Etheldreda remained entire, while those of St. Withburgh remained not only intact, but also fresh and with flexible limbs! She looked as if she were alive. This account was recorded by Monk Robert of Ely after the translation.

We see that in this way the Lord showed his special favor to Withburgh (although this is not to diminish the importance of other saints), who had lived as an anchoress in seclusion for many years until her nineties, gaining the abundant grace of God. In England there were just a handful of records when saints’ relics remained absolutely incorrupt centuries after their repose. Unfortunately, the shrines with all the relics at Ely Monastery were destroyed by the “reformers” under Henry VIII in 1541. No traces of the relics survive; however, according to the present Ely Cathedral archivist, they do have now some fragments of the thirteenth century shrine base, and an intriguing shrine structure, which was once thought to have been St. Etheldreda’s but which, as the architectural historian John Maddison suggests, may have been the base of St. Withburga's shrine (John Maddison, Ely Cathedral Design and Meaning (2000), p. 81). And now let us talk about the holy places where the saintly princess and abbess Withburgh is remembered.

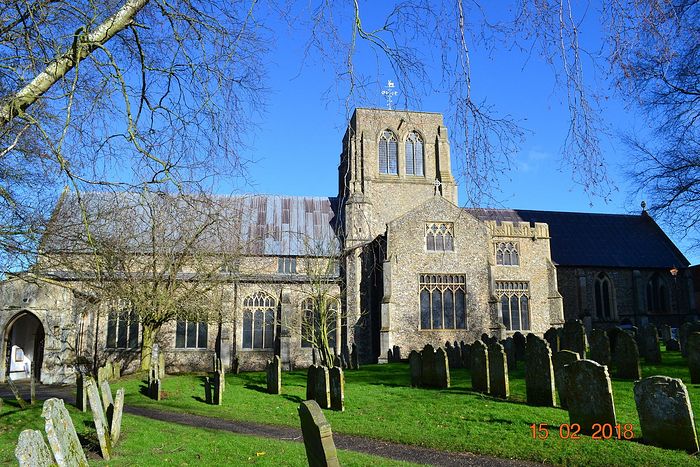

St. Nicholas Church and St. Withburga's well in Dereham, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Dereham church)

St. Nicholas Church and St. Withburga's well in Dereham, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Dereham church)

St. Withburga's well and a plate above it in Dereham, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Dereham church)

St. Withburga's well and a plate above it in Dereham, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Dereham church) The pretty market town of Dereham (until recently: East Dereham; the name possibly meaning “deer enclosure”) stands in the heart of Norfolk. The convent founded on this site by Withburgh existed until the late ninth-century Danish raids. In the 960s Ely Monastery helped restore the church at Dereham and, though St. Withburgh’s relics were moved to Ely, pilgrims continued to come in great numbers to the Dereham holy well through the Middle Ages. After the Reformation even the veneration of wells was prohibited. The well was half-forgotten, but in the late eighteenth century a bathhouse was built over it in the hope that the town would become a famous resort. However, the structure never became popular and in 1880 a local priest got permission to pull it down. After that the well was surrounded by iron railings to protect it. Since the 1950s St. Withburgh’s well has been kept clear permanently, although access to it is allowed only at particular times of the year. Flowers grow around the well. It is situated in the grounds on the west side of the town’s large St. Nicholas Church where Withburgh is commemorated in many ways. Each year on the first Sunday of July (closest to her feast-day) the congregation has a service in St. Nicholas Church that concludes with the Rector dipping a sprig of rosemary in the water from the well and sprinkling it among the worshippers. The present church dates back to the twelfth century, though it existed in Saxon times. In the late eighteenth century its tower was used as prison for holding French prisoners of war, one of whom, the officer Jean de Narde, is buried in this churchyard. Dereham was damaged during an air raid in the First World War, but the church was left unscathed.

Painting of St. Withburgh on the fifteenth-century screen in the Lady Chapel of St. Nicholas Church, Dereham, Norfolk (kindly provided by the churchwarden of St. Nicholas Church)

Painting of St. Withburgh on the fifteenth-century screen in the Lady Chapel of St. Nicholas Church, Dereham, Norfolk (kindly provided by the churchwarden of St. Nicholas Church) Among the notable residents of Dereham was the poet William Cowper (1731-1800), who composed Olney Hymns, died and was buried at St. Nicholas’, where he is commemorated in stained glass. The temple boasts of three monuments commemorating St. Withburgh: a fine new sculpture depicting Withburgh, which was made by a nun who was a member of the congregation for many years; a painting of Withburgh on the fifteenth-century screen (in the Lady Chapel) which came from Oxborough Church; and a depiction of the saint on the painted panel behind the High Altar. This interesting church has a wealth of other gems. They include a 1480 “seven-sacrament font” containing carvings of the seven sacraments on all its sides, one of the few surviving early “eagle-lecterns” in the country (dating to the same time), a plaque in commemoration of many church rectors throughout the centuries on one of the church walls, and so on. Its chancel, the Lady Chapel, transepts with splendid ceiling artworks and numerous chapels are filled with many delights from antiquity and modern times. Most of the stained glass is from the Victorian era. St. Nicholas’ uniquely has two towers: a late medieval detached massive bell-tower and a newer lantern-tower in the church crossing providing the church with light. Even the temple’s 500-year-old porch is adorned with religious carvings and figures.

The tiny village of Holkham (the name possibly means “holy village” or “homestead in the hollow”) now consists of a few farmers’ cottages. The nearest town is Wells-next-Sea. The village sits on the territory of the picturesque eighteenth-century Palladian stately home called Holkham Hall (belonging to the Earl of Leicester, it covers 4,000 acres), surrounded by the Holkham national nature reserve, with a deer park (up to 3,000 deer grazing there) and a lake and a beach nearby. The huge flint church, standing on the site of its eighth-century predecessor, can be found at a distance from the village in a woodland clearing, high on a circular mound. It is the only church in the world dedicated to St. Withburgh and keeps her holy memory. Officially the temple is situated on the grounds of the estate, and in winter, services are held in the hall’s private chapel.

Saxon remains of an earlier church (burned down by the Danes) along with a Norman structure were discovered at the church’s west end during excavations. The Norman church was rebuilt on the same site in the thirteenth century in the Early English Gothic style, and the present bell-tower basically dates back to that period. The tower at one time was used as a dwelling and also a telegraph. In the fourteenth century, the temple was extended in the Decorated Gothic style, but by the 1700s it had fallen into disrepair. In 1767 Lady Margaret, the Countess Dowager of Leicester, initiated a large-scale repair program in the temple, which saved it from collapse and considerably beautified it.

View of the chancel of St. Withburgh's Church in Holkham, Norfolk (kindly provided by the Holkham parish)

View of the chancel of St. Withburgh's Church in Holkham, Norfolk (kindly provided by the Holkham parish) 100 years later, an extensive renovation (in fact a rebuilding) program was self-sacrificingly sponsored and supervised by Lady Juliana (1825-1870), the wife of the second Earl of Leicester. She is commemorated inside the church in a memorial; her grave was initially in the purposefully-built church mausoleum, but over thirty years later she was reburied in a special plot in the churchyard (her coffin was in perfect condition). The reconstruction was designed by the architect James Colling (1816-1905). In the 1990s, the seventh Earl of Leicester continued the tradition of restoring and redecorating St. Withburgh’s. The only memorial to our saint inside the Holkham church is the carvings on the end of the choir stalls that depict her holding a model of the church, with a doe at her feet (information taken from the booklet on Holkham church published by Maureen Marr and Richard Worsley in 2003, with the current churchwarden’s kind permission). The church retains many historic features including exquisite alabaster and marble monuments and the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth century windows. Other objects of special interest include the plentiful local Coke family memorials and twelfth-century coffin lids. The overall atmosphere inside is of a spacious, light, prayerful and warm church.

St. Withburga's new sculpture inside St. Nicholas Church in Dereham, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Dereham church)

St. Withburga's new sculpture inside St. Nicholas Church in Dereham, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Dereham church) In art St. Withburgh is usually depicted as a crowned abbess, often with two roe deer at her feet, sometimes with a church in her hand. She is represented on at least six Norfolk church screens and many stained glass windows. For example, she appears at Barnham Broom church holding a model of her church; at North Burlingham church holding a church and with deer at her feet; on Great Ryburgh church screen; on a fine stained glass at Fritton church (all of them in Norfolk); in St. Mary’s Church in Woolpit in Suffolk, where she is depicted on a fifteenth-century rood screen together with Sts. Etheldreda, Edmund and Felix.

Thus the memory of this holy virgin, solitary, visionary, royal princess and abbess is preserved in her native region, and we hope that her veneration will increase among the Orthodox.

Holy Mother Withburgh, pray to God for us!