St. Chad (Ceadda) was born in the early seventh century and reposed on March 2 (according to the old calendar), 672 or 673. Pious English people, especially ordinary folk, have deeply loved and venerated this saint for more than 1300 years as one of their protectors. His veneration is similar to that of Sts. Aidan and Cuthbert of Lindisfarne and Swithin of Winchester; he lived absolutely in the same spirit with them. Thirty-three ancient parish churches and several holy wells across England are dedicated to him, in addition to numerous modern Anglican and Catholic dedications. The name “Chad”, which is perhaps of old Welsh origin and means “battle”, remains a boy’s baptismal name both in the UK and the USA to this day. Who was this saint?

Most of the information on St. Chad’s life can be found in the work by the Venerable Bede of Jarrow, The History of the English Church and People, written in 731. St. Chad from time immemorial has been venerated as the apostle of Mercia, the largest of seven early English kingdoms, which was inhabited mostly by Angles. The Kingdom of Mercia (meaning “borderlands or marches”) existed from 527 till 879 and stretched from the North Sea shore in the east to the River Severn and the Welsh border in the west. During its domination it comprised (fully or partially) the territories of the present-day counties of Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Rutland, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Staffordshire, the present West Midlands, north Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Shropshire, Cheshire and parts of today’s Greater Manchester and Merseyside.

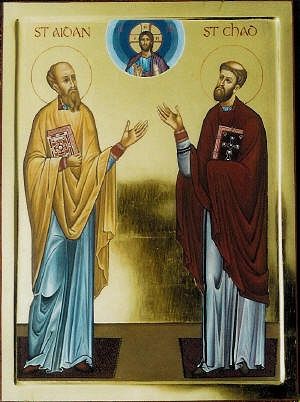

Chad was the youngest of four brothers, all of whom devoted their lives to the service of God. Their names were St. Cedd (who became a bishop and preached in Mercia and Essex; feast: October 26), St. Cynibil (a priest, feast: March 2), Caelin (a priest) and St. Chad who also became a bishop. They were born and brought up in the kingdom of Northumbria in the north of England. As a boy and adolescent Chad studied under St. Aidan, the apostle of Northumbria, in his most famous Lindisfarne (Holy Island) Monastery in the Irish tradition. Later, after Aidan’s death in 651, the young Chad together with other ascetics, among whom was St. Egbert,1 moved to study in Ireland, most probably at the great Rathmelsigy Monastery. There they lived the monastic life, persevered in prayer and fasting and were absorbed in the contemplation of the Holy Scriptures.

About the year 664 Chad returned to England and was ordained priest, while Egbert remained in Ireland. In the same year Chad’s eldest brother, St. Cedd, who had founded and ruled the monastery of the Mother of God in Lastingham in Northumbria (now a village in North Yorkshire), died of the plague and Chad succeeded him as abbot. As Abbot of Lastingham Chad became famous as a holy man, meek in his conduct, versed in the Holy Scriptures and zealous in putting the words of the Gospel to life. Nearly at the same time young St. Wilfrid (a great missionary and apostle of Sussex) was appointed bishop of Northumbria. However, as a result of the plague, there were almost no bishops in the whole of England to consecrate him. So Wilfrid travelled to Gaul for his consecration but delayed there for several years.

Time passed. King Oswiu, desperate for a bishop, sent Chad to Kent (to the very south), so that the Archbishop of Canterbury could arrange his consecration as a bishop for Northumbria. But reaching Canterbury, Chad learned that the holy Archbishop Deusdedit had reposed by that time and the new archbishop had not yet been appointed. From Kent Chad had to travel to the Kingdom of West Saxons where he was met by Bishop Wini who, together with two British bishops from Wales, performed his consecration. Chad returned to Northumbria and began to serve as the head of the diocese with the new center in York (then it bore the Roman name Eboracum).

According to Bede, in his new post Chad dedicated all his energies to maintaining the truth and purity of the Church through humility, moderation, and learning. He walked from cottage to cottage, from settlement to settlement, visiting many villages, towns and fortified localities in his diocese. Wherever he went, he preached the Gospel, travelling not on horseback but only on foot. In this he certainly imitated St. Aidan, both of whom evangelized after the example of the Apostles. He tried to teach the ways and customs of his brother Cedd, who was regarded as a saint, to the local population. The inhabitants of Yorkshire came to love this self-sacrificing and earnest bishop. At last, Wilfrid returned to England after four years of absence. Seeing that a new bishop had been appointed for his see, he humbly retired to Repton Monastery in Yorkshire which he had himself founded.

In 669 the new Archbishop of Canterbury came to England. This was the Greek St. Theodore, aged sixty-seven, who was destined to unite the English Church and reconcile it with the British Church in Wales. After his arrival Theodore set off travelling across the country, examining the dioceses and trying to put things in order where needed. Soon he learned that Chad had been consecrated “irregularly” because the two Welsh bishops, mentioned above, were not reconciled with the English Church and refused to comply with the decisions of the Synod of Whitby (663-664); for example, they still calculated Easter according to the lunar calendar, as opposed to the rest of the Christian world. Thus Chad was asked to leave his see and Wilfrid was appointed as Bishop of York instead. The holy man immediately retired to Lastingham and wrote a gentle answer to Theodore: “If you find my consecration wrong, I will gladly step down. Frankly, I always considered myself unworthy of it. And, being unworthy, I only agreed to accept this rank in obedience to the king’s order.” Receiving this meek answer and learning about the piety and ascetic life of Chad, Theodore decided that Chad must not refuse the episcopate; instead, he ought to be consecrated again in accordance with the canons.

In the year 669 the fourth bishop of Mercia, named Jaruman, passed away. At that time Mercia was ruled by King Wulfhere (658-675) who under the influence of his saintly wife, Queen Ermenhild, was converted to Orthodoxy and actively supported the Church. After the death of Jaruman, Wulfhere asked Theodore to send him a bishop and Theodore decided that Chad was the best match. So this gentle and humble man was entrusted with ruling a huge diocese comprising the whole of Mercia, which then was still mostly pagan. Knowing that Chad used to spread the Gospel on foot, Theodore provided him with a horse so that his journey to Mercia would not take too long. But the saint hesitated, being fully immersed in labors of piety; then Theodore lifted him and seated on the saddle with his own hands, urging the man of God to hasten to carry out this important ministry. As Bede wrote, Chad out of obedience accepted the rank of Bishop of the Mercians, and following the example of the Church Fathers of old times, he ruled his diocese in great holiness of life.

Although the first see of Mercia had been located in Repton in present-day Derbyshire, Chad chose the town of Lichfield in present-day Staffordshire as his see (Lichfield was probably named after a Roman settlement two miles away whose name meant “Greywood”) which was not far from the Mercian capital in Tamworth. Wulfhere granted Chad land for the establishment of a monastery “at the wood” in the province of Lindsey, corresponding to the county of Lincolnshire. Most researchers identify that place with the village of Barrow-upon-Humber in North Lincolnshire, where not long ago the remains of St. Chad’s monastery were excavated and a local street named after the saint; this village also has a Norman parish church of the Holy Trinity with some pre-Norman details. It is unknown for certain which rule Chad introduced at his monasteries during his ministry in Mercia; but what is certain is that he was under the strong influence of Irish monasticism and Lindisfarne with its Irish traditions.

The saint built a church in Lichfield and a small solitary hut for himself not far from it, where he could spend time alone or together with seven or eight of his disciples, studying the Scriptures and praying, when he had time between his missionary journeys. He also built a monastery near Lichfield. The saint of God ruled his diocese for only two years and a half, but during that time through the abundant grace of God he achieved so much in bringing people to Christ and evangelizing the area that he later became known as “the Apostle of Mercia”. Indeed, it is a miracle that a small, mild, modest and (by the end of his life) frail man over the span of two and a half years covered such a vast territory, without good roads or any transport, with numerous dense forests and marshlands, still with a large number of pagans and their dangerous customs, and succeeded in starting the enlightenment of the entire territory and erecting dozens of churches, chapels, crosses and holy wells in every part of the region! The Lord’s power is manifested in men’s weakness.

Among Chad’s virtues enumerated by Bede are temperance, humility, self-denial, fervor in teaching, praying, voluntary poverty and, above all, the fear of God. Trumbert, a monk from Chad’s Monastery who subsequently became Bishop of Hexham and a mentor of Bede, told him much about the character of Chad. For example, whenever a strong wind started while Chad was reading in his hut, he would immediately call on the mercy of God and entreat Him to have pity on humankind. If the storm got more intense, he would close his book, prostrate himself and pray with more fervor. And if the wind turned into a thunderstorm with rainfall and lightning, which made the locals tremble with fear, he would go into his church and unceasingly recite psalms and prayers in quiet, until the skies cleared. When asked why he did so the saint used to reply: “The Lord disturbs the air, provokes the wind, sends thunder and lightning from heaven in order to call on us for the fear of God; to remind us of the Last Judgment; to make us suppress our pride; to crush our disobedience and lead our souls to that great and terrible day… So, with all due fear and love we must be mindful of His warnings through such signs in heaven… When it happens, we need to implore Him to have mercy on us, to confess all hidden sins and vices in our hearts and to cleanse our souls with all zeal.”

Chad blessed a holy well in Lichfield beside his hermitage-hut and he used its water for baptisms. According to tradition, he would also immerse himself in his well at nights for continual prayer, as did many other saints of the Isles. Its water was used for healing the sick of many physical and mental diseases. People from far and wide would flock to his modest hut and receive spiritual advice, consolation, instruction and healing. His strong and meek words always touched people’s hearts, and he kindled the desire for genuine Christian life in their souls. The saint healed many people during the epidemic of the plague, though he became a victim of this disease himself.

There were future prominent Church figures and saints among the disciples of Chad and among those who knew him, we should mention: St. Owen of Mercia (feast: March 4),2 St. Hibald of Lindsey (feast: December 14),3 and the holy passion-bearers brothers Wulfhad and Ruffin.4 Besides, it is known that Chad instructed the young St. Werburgh who later became the illustrious abbess of three Mercian convents and patroness of Chester.

Shortly before his repose, Chad contracted the plague, which was rife and rampant in the England of that era. Bede describes his death with this very moving account. Once St. Owen, mentioned above, was alone in Chad’s hut while all the other brethren had left, and the bishop himself was praying in the church. Suddenly Owen heard extraordinarily pure and joyful singing; it was moving in the air from the east and reached the church and penetrated it. Half an hour later the same sweet choir of voices reappeared—it “went out” of the church through the roof and slowly ascended to heaven. Astonished, Owen left the hut. At once Chad called upon him and the other monks to gather around him and informed them that the day of his repose was near. He invoked them to follow all monastic rules with undiminished diligence and constancy, to practice all that he had taught them both by word and deed, and to imitate the lives of the Fathers of olden times.

He said: “A beloved guest has visited me today in order to take me from this world. So, please, pray for me before my meeting with the Lord, and do not forget to prepare for your own departure to Him by fasting, prayer and good works, for we never know when we may die.” When the other monks had left, Owen asked Chad about the unusual singing he had heard. And Chad replied: “These were the holy angelic powers that descended from heaven to warn me that they would return in seven days to take my soul with them. But I beg you not to tell anyone before my death.” And his words came true. He caught the plague and got weaker every day. On the seventh day the holy man received Communion for the last time and his pure God-loving soul departed his body for eternal bliss. At the moment of his death St. Egbert in Ireland, many miles away, in a vision saw the soul of St. Cedd (who had reposed eight years before) ascending from Paradise with an assembly of angels and taking the soul of Chad with them in great glory.

As Bede writes, Chad was first buried in the church of the Mother of God in Lichfield that he had built. When St. Peter’s Cathedral was built in the city in about 700, his relics were translated and enshrined in it. The translation was accompanied by miracles that did not stop afterwards. For example, one lunatic who in his madness wandered from one place to another entered St. Peter’s Cathedral unnoticed and spent the night there. In the morning he appeared before people absolutely sound, and recounted his miraculous story of healing near St. Chad’s relics.

It was providential that Bede describes St. Chad’s shrine in detail because 1100 years after he had written these words his account helped in the designing of its replica for Birmingham Cathedral. Bede wrote that Chad’s reliquary was wooden and resembled a small house, with a hole in the side through which those who visited could insert their hands and take some of the dust; the dust was mixed with water, and this mixture was drunk by both the faithful and animals—and hundreds cases of healing were reported. Lichfield Diocese founded by Chad exists to this day—one of the oldest dioceses in England. During the reign of King Offa of Mercia (757-796) who had high ambitions and dreamed of ruling the whole of England and controlling its Church, there appeared the Archdiocese of Lichfield, as Offa’s attempt to create a “new Canterbury” right within his own kingdom. However, this archdiocese existed for just over ten years and was abolished after Offa’s death.

The relics of Chad were venerated in a succession of cathedrals in Lichfield until the Reformation. After the Norman Conquest the cathedral at Lichfield was first rebuilt by the Normans in the Norman style (1085-1140), and late in the twelfth century construction of the new, Gothic cathedral began on its site (continued from 1195 till 1340). Translations of the saint’s relics took place in 1148, 1296 and between 1360 and 1385—this time into a shrine with a marble structure, adorned with gold and precious stones. Chad’s relics finally ended up in the Cathedral’s splendid Lady Chapel. At a certain time his head-relic was separated from the main body and enshrined in a smaller reliquary inside a purpose-built chapel with a balcony on an upper story of the Cathedral, and it has been known as “St. Chad’s Head Chapel” ever since.

During the Reformation, the Bishop of Lichfield of that time appealed to Henry VIII, asking him to spare St. Chad’s shrine in their Cathedral. This was done but only for a few years; the reliquary was eventually desecrated by radical Protestants and a large part of the saint’s relics destroyed. However, some four long bones of Chad were secretly hidden and kept by recusant Catholic priests and their relatives down the centuries. During that time the holy relics even visited France, were preserved in Staffordshire, and after the Catholic Emancipation they were enshrined in the new Roman Catholic Cathedral in Birmingham in the nineteenth century, where their due veneration continues to this day.

The High Altar of Birmingham Catholic Cathedral containing the reliquary with St. Chad's relics (photo by James Bradley)

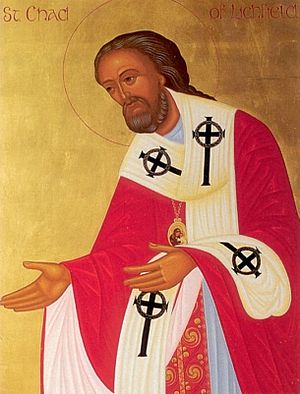

The High Altar of Birmingham Catholic Cathedral containing the reliquary with St. Chad's relics (photo by James Bradley) The liturgical and popular veneration of Chad was resumed, especially in the twentieth century, by Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Anglicans. Numerous Orthodox icons, Catholic and Anglican stained glass windows and statues are dedicated to this saint across the country, to say nothing of names of streets and ancient toponyms associated with him. There is a Russian Orthodox parish (the Diocese of Sourozh) in honor of Sts. Aidan and Chad in the city of Nottingham and a Greek Orthodox community (the Patriarchate of Constantinople) of the Ascension and St. Chad in the town of Rugby (Warwickshire). Such place-names as Chadkirk, Chadwick, Chadburn, Chaddesley, Chadsmoor, Chaddesden and many others were in most cases derived from our saint’s name. However, the place-name “Chadwell”, which is common in England, does not necessarily mean, “St. Chad’s well”—it may also mean “cold well” or be associated with some other person. An interesting example is Chadwell St. Mary in Essex, which until recently had a holy well, known as St. Chad’s, though it must have been a confusion as this saint never travelled to Essex; it was his brother, St. Cedd, who labored in this region.

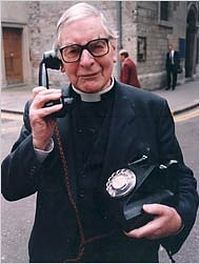

Many schools in England are named after St. Chad and an independent college of Durham University bears his name as well. There are a number of sayings that connect the weather, agriculture, and this saint’s feast-day (March 2 for Non-Orthodox Christians); this is the case with many saints. For example: “March 1, upon St. David’s Day put oats and barley in the clay,” “March 2, St. David and St. Chad, sow the peas good or bad”, “March 3, first comes David, then comes Chad, and then comes Winnold [St. Winwaloe of Brittany] as though he were mad”—the later is allusion to gales prevalent at this time. The most famous man with the name “Chad” among our contemporaries is Chad Varah (1911-2007), an Anglican priest and founder of “The Samaritans”—a British voluntary organization providing a telephone service for the suicidal and despairing. It was started by him in 1953 in the cellars of the London church of St. Stephen, Walbrook, with one telephone, and it now has over 200 branches throughout the country; it has saved the lives of many people, which is so close to the spirit of St. Chad. Now let us talk about great shrines associated with our saint.

The small, elegant and picturesque city of Lichfield is sixteen miles north of Birmingham. Its population is 32,000. Since the seventh century it has been considered a holy place due to the shrines associated with St. Chad, and thousands of pilgrims visit them annually. In the eighteenth century Lichfield, became a well-known center of culture, literature and science. It was home to such great figures as Elias Ashmole (1617-1692; an antiquary; he donated his huge collections, library and manuscripts to Oxford University, forming the nucleus of the Ashmolean Museum); Samuel Johnson (1709-1784; a lexicographer, writer, author of The Dictionary of the English Language and The Lives of English Poets); Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802; a scientist, physician, inventor and poet, grandfather of Charles Darwin); Anna Seward (1742-1809; a talented poet and botanist); and David Garrick (1717-1779; a playwright and actor).

The city is dominated by its ancient Anglican Cathedral of the Mother of God and St. Chad. It is an exclusive architectural gem and perhaps one of the most attractive English cathedrals. It is the only medieval cathedral in England with three spires (in honor of the Holy Trinity) which are nicknamed “the Ladies of the Vale”. The cathedral was built of sandstone. It was badly damaged during the English Civil War, being several times besieged by both the Royalists and Parliamentarians—a garrison and stables were once housed within the cathedral and as a result nearly all of its medieval statues, stained glass and most of the roof were destroyed. The interior was carefully restored in the Neo-Gothic style during the nineteenth century by the architects James Wyatt (1746-1813) and George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878).

The exterior is awesome. It has around 160 statues in total which project directly from the stonework rather than sit in special niches as elsewhere. Only a few are medieval—most are nineteenth and twentieth century replicas. The statues were cast by the sculptors Robert Bridgeman (1844-1918); Mary Grant (1831-1908); and, notably, Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, a daughter of Queen Victoria (1848-1939). The west front has as many as 113 statues: of the patriarchs, the prophets, some women of the Old Testament, all Archangels, Apostles, some early Church saints, several English saints (St. Chad thrice, St. Edith, St. Theodore, St. Werburgh, Alfred the Great), Old English kings and post-Conquest kings till Richard II, some bishops associated with Lichfield, and more. There are also statues on the north and south transepts, the chapter-house, the choir, the Lady Chapel, the Consistory Court.

As you enter the Cathedral, you are impressed by its splendor, space, glory, the atmosphere of antiquity and geometric perfection. The choir, aisles, presbytery and central tower are in the Norman Transitional and Early English styles. The transepts date from the period between 1220 and 1240; the style is Early English. The octagonal chapter-house of c. 1250 has two stories, with an attractive central column and a number of pillars. The vestibule to the chapter-house is in line with the spirit of St. Chad—it has a remarkable feature, a place where on Holy Thursday the washing of feet took place. There are thirteen seats where the poor whose feet were washed would sit. The nave was built by 1285 in a style between Early English and Decorated. The west end provides a splendid view of the length of the church. The west front dates from early fourteenth century. The Lady Chapel was completed by 1340 in the Decorated style. It is one of the most beautiful parts of the cathedral. It was here that the famous Herkenrode Abbey’s sixteenth-century glass collection, depicting the life of Jesus, was taken from Belgium in order to save it from Napoleon. This glass, along with other stained glass and sculptures within the Cathedral, replaced those that had been lost in the Civil War.

Regarding the memory of St. Chad, this Cathedral has several surprises. Firstly, a new shrine in commemoration of this saint was made not long ago and was placed behind the high altar in the chancel. Secondly, the chancel has a number of fine tiled depictions of scenes from the saint’s life. Thirdly, the supposed position of the original saint’s shrine is marked by a plaque on the floor near the Lady Chapel. Fourthly, there is at least one Orthodox icon of St. Chad within the cathedral and candles are usually lit on either side of it. (The Cathedral has acquired other icons in recent years). Fifthly, the saint is commemorated liturgically in the Cathedral during services, and especially in the chapel where his head-relic was once kept—this chapel still preserves its old atmosphere of holiness.

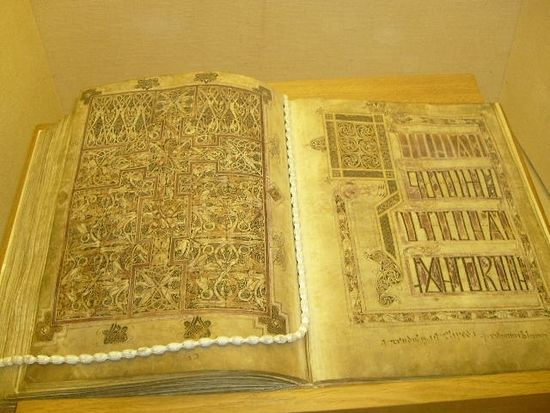

Sixthly, there is the precious eighth-century illuminated Gospel, known as St. Chad’s Gospel (also as St. Teilo’s Gospel or the Lichfield Gospel) on display in the chapter-house. Its origins are unknown. It is in a very similar style to the famous Lindisfarne Gospels. It was created either in Wales or Mercia early in the eighth century and for the past 1000 years has been kept in Lichfield; there was another volume of the Gospel with the same name which was, unfortunately, lost during the Civil War atrocities. This vellum manuscript is a masterpiece of early English art. It has 236 folios, which include the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and partially of Luke. Some of its marginalia are in Old Welsh, making this gem virtually the earliest example of surviving Welsh language writing. Who knows, perhaps this very Bible was read either by St. Chad or St. Teilo.

And, seventhly, a true miracle occurred in 2003 when archeologists excavated under the nave of the cathedral. They discovered a number of extremely interesting artefacts, more or less confirming that the heart of the first Saxon church on this site was here. The most remarkable find was an eighth or ninth century limestone panel depicting an angel. The angel’s carving was still of excellent quality. Although initially broken into three pieces, it has been carefully restored. The researchers presume that it was a panel which formerly adorned or was part of St. Chad’s shrine. It is believed that it is only half of the Annunciation panel: this fragment depicts the Archangel Gabriel and the other half (perhaps it is yet to be discovered) depicts the Mother of God. This wonderful relic has been called the “Lichfield Angel”: it has also been on display in the chapter-house and is considered to be one of the earliest and finest surviving stone sculptures of the Anglo-Saxon era.

Artefacts from the “Staffordshire Hoard” are exhibited at the chapter house as well. This hoard was found in a field near Lichfield in 2009 and contains the largest existing collection of early English golden and silver metalwork (some 3,500 items in all were found). There are plans to install a statue of St. Chad beside the Cathedral in the near future.

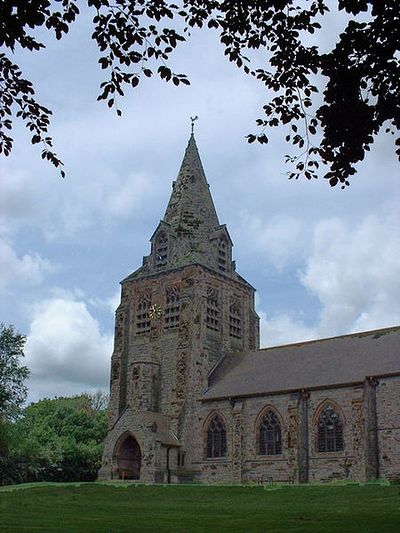

On the northeast of Lichfield, on St. Chad’s Road, stands the very ancient St. Chad’s parish church. It was here that the saint lived in his hut, baptized and prayed. The present church was built on the site of his small monastery in the twelfth century. A statue to its patron was erected on its south porch in the twentieth century. The holy well, the waters of which were used by the saint, survives within the graveyard of this church. It is still a popular pilgrimage destination for Christians of different traditions; the well is annually decorated in a ceremony known as “well-dressing”. A stone well house was built by the well in the 1830s when the pilgrimages resumed; it was demolished in the 1950s and replaced by a simple wooden structure.

Apart from this, there are also St. Michael’s Church, Christ Church and St. Mary’s Church in Lichfield. Notably, Protestant and Catholic martyrs of England are commemorated at St. Mary’s. Some of them were executed there on the market square, others were only linked to Lichfield. Among them was Edmund Gennings who was first disemboweled and then beheaded in London in 1591 at the age of twenty-four only for being a Catholic. One of the church plaques commemorates George Fox, the founder of the “Quaker” movement, who visited this town.

The Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of St. Chad stands in the center of the huge city of Birmingham. It was built early in the 1840s according to the design of Augustus Pugin—one of the first Catholic grand churches constructed after the repeal of the Penal Laws. It is here that for the past 170 years a portion of St. Chad’s holy relics has been venerated, especially on his feast-day, with prayers and processions. They are enshrined in a golden reliquary above the high altar, in a place of honor. The shrine was built in accordance with the description by Bede of the saint’s original shrine. St. Edward’s Chapel at the Cathedral has a set of stained glass images relating the long story of the wanderings of Chad’s relics between the Reformation and their arrival in Birmingham. In the late twentieth century, the relics were carbon-dated by Oxford University and appeared to be of the seventh century, the time of St. Chad. This bright and graceful Cathedral also has a sixteenth-century statue of St. Chad holding a model of Lichfield Cathedral, cozy side-chapels for quiet prayer, and other sights. In 1940, during the Second World War, one bomb went through the roof of this Cathedral, but bounced from the floor to central heating pipes, causing water to burst from the pipes and extinguish the fire. It was a miracle of St. Chad that the damage was not so serious.

Some parish churches are dedicated to St. Chad on the territory of his former first Diocese of Northumbria: the charming church in the village of Middlesmoor in North Yorkshire, also known as “the church in the dale,” in a very picturesque setting (there is an early inscribed preaching stone, “St. Ceadda’s cross,” inside the church, thought to have been erected there by the saint himself, along with a Saxon font); churches in Saddleworth and Rochdale in Greater Manchester (legends associated with these churches abound); in the hamlet of Sproxton in North Yorkshire (built under Elizabeth I) and so on.

St. Chad's Church in Sproxton, North Yorkshire

St. Chad's Church in Sproxton, North Yorkshire

Yet the majority of his churches can be found in the Midland counties: in the village of Bishop’s Tachbrook in Warwickshire; in the village of Tushingham in Cheshire, which has a parish church and an old chapel of St. Chad; one of the churches in the town of Shrewsbury in Shropshire is dedicated to St. Chad5—the first church in this town was built by him (the present circular church was built in 1792 in place of the previous one that had collapsed due to old age in 1788; it is one of the most famous and beautiful churches of this saint, having an Orthodox icon of Sts. Aidan and Chad in the chapel dedicated to St. Aidan); in the village of Farndon in Cheshire on the River Dee; in the town of Winsford in Cheshire (St. Chad preached on this spot and baptized in a local forest well; the church has a Saxon stone); in the town of Kirkby in Merseyside (the first church here was Saxon; its font is Norman, and it has interesting carvings); and two parish churches in the industrial city of Wolverhampton near Birmingham.

There is also a church in the village of Harpswell in Lincolnshire (built in 1042; one of the few English churches to preserve a Saxon tower. It also has medieval glass, ornate oak pews and a Norman font); a parish church of St. Chad in the Early English style and an Anglican primary school in Dunholme in Lincolnshire; in the village of Welbourn in Lincolnshire (the church is Norman; people believed if they hung a carving of a sore body part on its south door then the ailment would be cured); a very ancient church in the old isolated village of Church Wilne in Draycott parish in Derbyshire (the saint preached and had a holy well nearby; a local reservoir is named after him); churches in the villages of Stockton (with a fifteenth-century tower), Montford and Boningale (from the twelfth century; it has a portion of a medieval cross at churchyard) in the charming Shropshire countryside; parish churches in the following Staffordshire locations—Hopwas, Burton-on-Trent (one of numerous churches of this town), Freehay, Bagnall, Longsdon, Pattingham (from the early thirteenth century; it stands on the site of a Saxon church and its churchyard has an early English cross shaft), Slindon and the town of Stafford (this extremely interesting twelfth-century church has over 100 carved figures; it was restored in the nineteenth century by George Gilbert Scott) and many others. A large number of St. Chad’s churches across Midlands are concentrated in peaceful rural locations, reminding us of and drawing us closer to the spirit of this holy man.

Anglican churches dedicated to St. Chad can be found in the town of Holt on the River Dee in county Wrexham, Wales; in Toronto, Canada; and in Chelsea, Australia.

London once had a famous St. Chad’s well in St. Chad’s Place near King’s Cross. Indeed, London had no fewer than twenty holy wells in ancient times, most of which were connected with the River Fleet. St. Chad’s well was extremely popular for healing many diseases, and due to this the saint was proclaimed as the patron of sacred wells and springs. There are several surviving holy wells of St. Chad in England, though some of them are called simply “Chad well” and it is not evident that all of them are named after our saint. They can be found in Lastingham (two other wells there are dedicated to St. Cedd and St. Owen); in Chadkirk in Greater Manchester near the town of Stockport (people used to bring small figures of sore body parts to this well); in Twyning near the town of Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire; in Chadwell Heath in Essex (in fact it is a replica of the original well); near the village of Bedhampton in Hampshire; near the tiny town of Clun in Shropshire; at Tinedale Farm in Lancashire; in the town of Midsomer Norton in Somerset; in Hammer (formerly Chadhill) over the Welsh border and others.

Holy Hierarch Chad, pray to God for us!

All reliable information on St Chad of Lichfield can be found in St Bede’s work, Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, in book III chapter XVIII and in book IV chapter III. Besides, there are a number of early and later traditions related to him, including oral ones. St Bede’s book is available online on the internet. There are dozens of places associated with St Chad in England, and I know that Lichfield Cathedral published a book on him some years ago (I am sure there are many other publications, including those of academics), though the original source is St Bede alone.