To St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco

Warm air bursts into the car window as the boundless expanse of the ocean passes by on one side, with the breathtaking views of the Sierra Nevada foothills on the other. At the stops we can smell the fragrance of the tender pink almond flowers that blossom this time of year. The Lord brought me to California in an absolutely miraculous way.

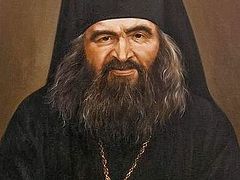

This is how it happened. I had finished a book dedicated to St. John of Shanghai the wonder-worker of San Francisco. In the process of my work on the book, St. John of Shanghai became ever closer and dearer to me, and the desire to venerate his relics, to visit the cathedral he built in San Francisco, the home where he brought his orphans from Shanghai grew ever stronger in me. I really want to meet some of his spiritual children from Shanghai before they depart to eternity—after all, they are no longer very young.

But a trip to San Francisco seemed practically impossible to me; I was also worried that my desire to write down the remembrances of his spiritual children were probably also senseless—certainly everyone who wanted to talk about Vladyka had already done so.

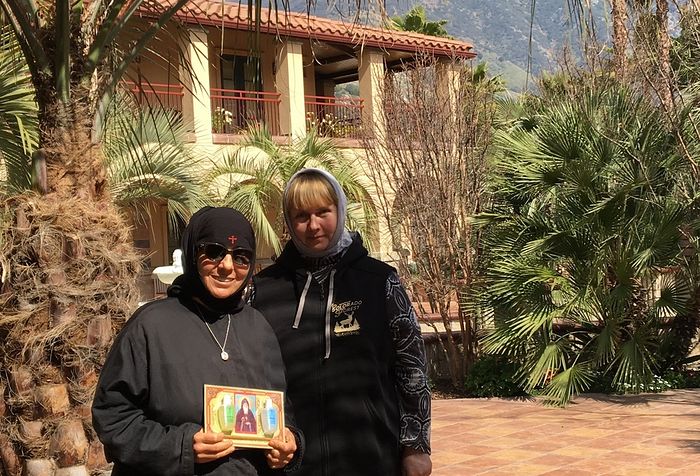

My dear travelling companions to Orthodox churches and monasteries of California, Natasha and Nastya.

My dear travelling companions to Orthodox churches and monasteries of California, Natasha and Nastya. But St. John of Shanghai showed me enormous mercy: Everything that seemed impossible became perfectly doable in one moment. I and my new friends Nastya and Natasha completed a large travel route in just a few days—from San Diego to the Convent of Life-giving Spring, founded by Elder Ephraim of Arizona not far from Dunlap, on the border of California and Nevada, and I was able to talk with Gerondissa Markella.

Then we arrived at San Francisco and prayed in the cathedral of the Mother of God “Joy of All Who Sorrow” and venerated the relics of St. John of Shanghai. We talked with Archpriest Peter Perekrestov, the cathedral’s sacristan, who has been serving for many years at Vladyka’s relics, has gathered a great deal of testimony and recollections about his holy life, and written an excellent book about the holy hierarch.

We also spent some time in the old cathedral, where Vladyka served while the new cathedral was being built, and met the rector, an American hieromonk, James (Corazza). He turned out to be a very warm and attentive pastor, and although the evening services had ended and the parishioners had dispersed, he despite being noticeably fatigued served a special travel moleben for me and my two companions, and even covered me with Vladyka’s mantle during the service.

The old cathedral in San Francisco, where St. John of Shanghai served until the new cathedral was finished.

The old cathedral in San Francisco, where St. John of Shanghai served until the new cathedral was finished.

I stood throughout the moleben on my knees by the analogion with the icon of St John of Shanghai, covered with his mantle, literally loosing the sense of time and space, as if I were not on earth but in Heaven.

We spent some time in the orphanage, where Fr. John led us on a tour and showed us the dining room, house church, and Vladyka’s cell. He even allowed us to sit in the armchair next to a full-size portrait of him.

I was also able to talk with several of Vladyka’s spiritual children. We were unexpectedly invited to the home of Benjamin Vasilievich Vorobiev from Pasadena—Vladyka John’s spiritual son. Benjamin Vasilievich had never before talked in detail about St. John, or his own family history.

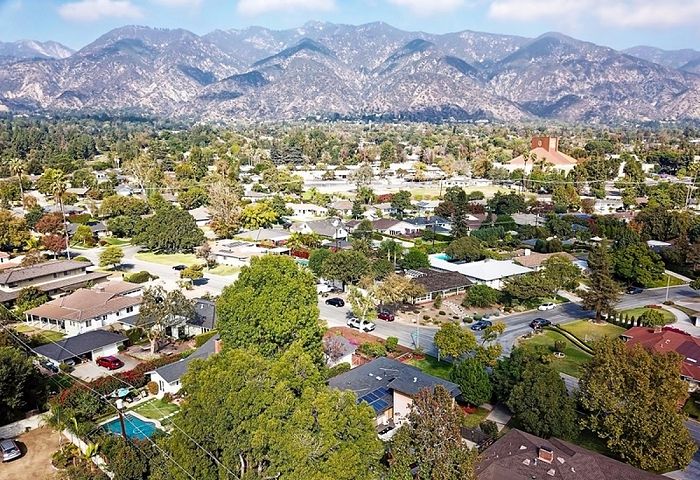

Nastya and I immediately set out for the Vorobievs. Pasadena is a quiet little town not far from Los Angeles. From our new acquaintances’ window we could see the mountains, and roses that blossomed outside. Benjamin Vasilievich’s charming wife, Elena Tigranovna, helped us very much—she had tried a long time ago to write down her husband’s memoirs, and when he grew tired of talking she told us much of it herself. At the conclusion of our meeting the Vorobievs fed us a delicious meal, and then they went outside to see us off.

Here is the story of Vladyka John’s spiritual son and alter server—Benjamin Vasilievich Vorobiev.

“My hands were still small, but I was already kneading dough with them.”

Benjamin Vasilievich’s mother, Evgenia Polycarpovna, was from Chita [in the Russian Far East]. Her family had moved to the Far East long ago, when the Russian Emperor was giving land away to settlers. Having received their portion, they began developing their household—gardening, orchard keeping, raising piglets and selling them at the Chinese Eastern Railway. They worked hard and enjoyed the beautiful nature of that region. They would hire workers to gather the harvest, and the mistress of the house would make dinner for them all herself.

Evgnia Polycarpovna often recalled how when she was little she was quickly made accustomed to working—she was taught to bake pies and kulich. She would sometimes show the children, “My hands were so small, but I was already kneading dough with them…” Later in Shanghai she would cook for the church. Papa worked more than everyone, and when he would return home exhausted he would ask his daughter to take the horse down to the river. That is how she learned to manage livestock.

A hard road

Evgenia grew up, got married, and had three children—in 1916 she had a son, Alexander, and in 1918 and 1920, she had her daughters Natalia and Nina. They lived in Siberia. Her husband, a White Army officer, died when the White Army retreated in the East. Along with the departing soldiers in 1922 civilians also moved—all those who could expect no mercy from the new regime. Evgenia, then still a young and beautiful woman, also did not wait around for the Reds to come—the widow of a White Army officer was not likely to find the conquerors condescending.

Evgenia harnessed the horse, sat her three children on the cart and set out upon the terrible road filled with dangers, along with the retreating White Army. This was less dangerous than trying to make it on their own; moreover among the Whites were military doctors who could give them medical help. Little Sashenka (Alexander) kept pestering his mother, “Klysa, klysa,” but she couldn’t for the life of her understand what he was trying to say. She only got it when she looked at the cart and saw an enormous rat—krysa in Russian—hiding under the straw.

The refugees wanted to reach China and they walked along the border of Manchuria headed for Harbin—a Russian city that was founded on Chinese land during the building of the Chinese Eastern Railway. An influenza epidemic was raging, and first her son fell ill, then little Ninochka.

One of the White Army officers who sympathized with the children and their mother came to their aid. This was Vasily Ivanovich Vorobiev, born in 1890, and a veteran of the First World War. With his help the fragile young woman was herself able not only to survive during this wartime, but also to save all three children and reach Harbin—the city of Russian railway workers.

The bitter fate of Russian Harbin

Having grown close in these terrible trials, Vasily and Evgenia never parted afterwards, and Vasily Ivanovich replaced the children’s father. They settled in Harbin, but would not live there for long. In 1935, the Soviet Union sold the Chinese Eastern Railway to the Chinese, and everything that the Russians had achieved in these lands under the tsar were lost.

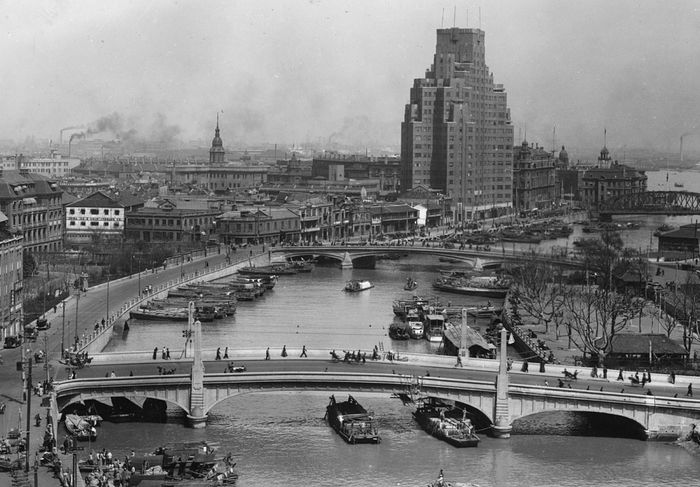

Then the great exodus of Russians from their beloved Harbin began. They moved further into the depths of China, mostly to the cosmopolitan city of Shanghai.

Shanghai

The Vorobevs again hit the road and finally ended up in Shanghai. In 1934 a fourth child was born—Benjamin Vasilievich, or Benya for short.

In those years, the port city of Shanghai with its foreign concessions and affiliates of companies known all over the world seemed to many to be the promised land. Here had appeared the latest inventions—electricity, trams, automobiles, and modern sewage systems.

England, France, the U.S.A, and Russia had received exterritorial rights in this city; that is, although their citizens lived in China they were not subject to the Chinese authorities or Chinese laws. After the Soviet Union declined its exterritorial rights, the situations for Russian emigrants in Shanghai became difficult—as Whites, they enjoyed the rights of free people, but they were people without any citizenship.

On the station square of Shanghai, local boys would watch for refugees and for a small sum would show them where the Orthodox church was located, where they could rent inexpensive living space, and where the pawn shops were. The owners of these shops would buy for cheap all the valuables of the Russian emigrants, which they would sell in order not to die from hunger.

The Vorobievs had no family valuables left, and so they had nothing to sell. But my mother had three sisters, and it turned out that they had left for Shanghai earlier, gotten married to non-Russians, and when Evgenia and her family had made their way to these relatives the latter helped them very much; they even bought their sister a two-story house. The Vorobievs rented out the lower floor, Vasily Ivanovich built an annex, and their life came together. True, this house had no heating and it was cold inside, and therefore the family would most often gather in the only warm room—the kitchen.

Vasily Ivanovich, like many Russian men, was a jack-of-all-trades—he could weld, fix things, and build. He knew how to do everything. He had worked all his life—he built bridges, fixed automobiles, learned to drive a car, and then became a bus driver.

Vladyka John of Shanghai

In 1934 (the year Benjamin Vorobiev was born), Bishop John (Maximovitch) of Shanghai, later of San Francisco, arrived in Shanghai. He labored many years for the unification and solidarity of the torn diocese, worked on the building of the cathedral in honor of the “Surety of Sinners” icon of the Most Holy Theotokos and the orphanage he founded dedicated to St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, the Voronezh wonderworker. People came day and night to Vladyka and he received them all with love. So, Bishop John certainly had enough to do…

The Vorobievs lived a twenty minutes walk away from the cathedral, and Benjamin’s mother, a deeply religious woman, would run to the church in all sorrows and joys. She would take her children with her, and Benya, you could say, grew up in the church. Bishop (from 1946, Archbishop) John of Shanghai served in the cathedral.

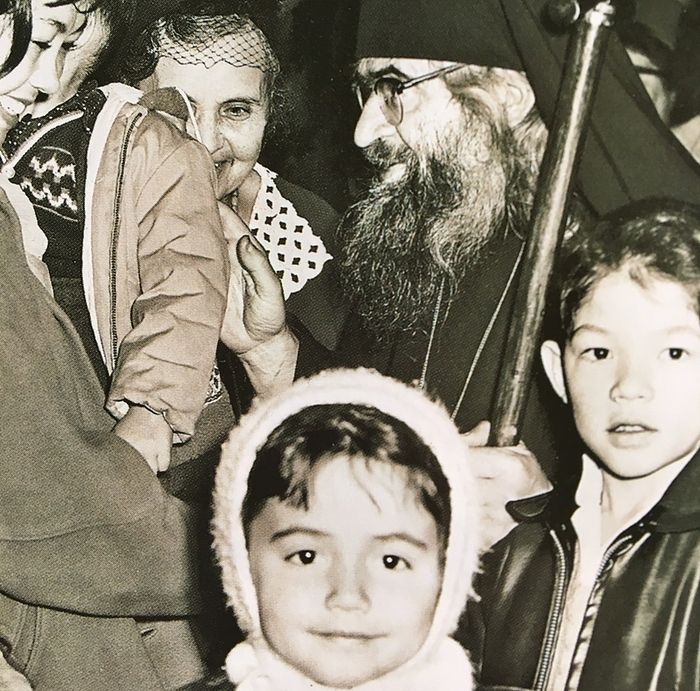

When Benya had grown some he began serving in the alter with Vladyka. He would come and put on a sticharion (the tunic worn by altar-servers) and try to be of use. But due to his young age he wasn’t able to serve very well. He would stand in the altar, walk around the church, go to Vladyka and stand there with him. It was very pleasant for his mother to see her son in church and not running the streets. Evgenia Polycarpovna was also a member of the women’s committee in the parish, and made food for the meetings.

The boy say how Vladyka respected his mother, and treated him with respect as well, and with a pure heart revealed to him all his thoughts and childish sins.

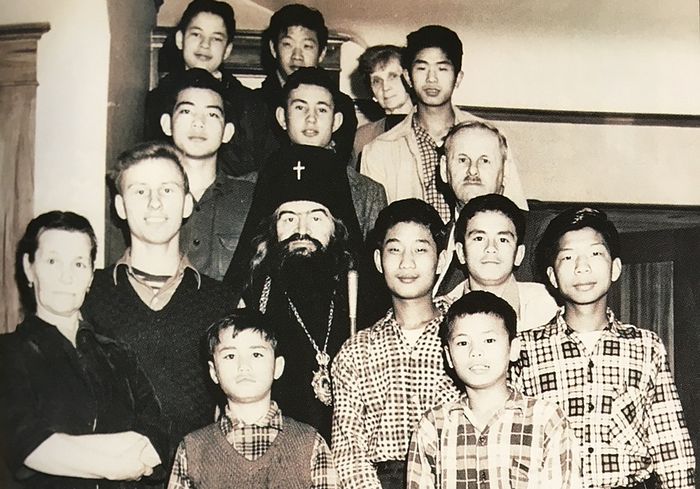

In one photograph is Vladyka John, Fr. Matthew, and Benya in the lower row in the center, the smallest of the toddlers, with flappy ears. Benya remembered well that across the street from the cathedral lived Boris Semeniuk; his mother, Olga Ivanovna prepared food for Vladyka and his alter servers. After services the boys always accompanied Vladyka to his cell. They knew that they would be given something tasty to eat there.

They ate, but Vladyka never hurried to sit down to table—he would stand off to the side and always give the children some kind of educational talk, explaining what feast day it was that day or some difficult ecclesiastical word. That is, it was not just lunch or dinner. The boys ran there to get something good to eat, but Vladyka would feed them with spiritual food.

After eating, the children would shout, “Thanks so much, Vladyka, we ate well!” This was a great joy for him.

Vladyka John’s trust in God

Once when Benya was still little he was standing in the cathedral and could feel that all the parishioners in the choir were particularly anxious that day. It was a great feast, there was to be a cross procession, but it was expected to rain. The sky darkened, a downpour was about to begin, and everyone was proposing to Vladyka that they put off the procession in order not to ruin the icons and vestments. In those difficult times they worried about every little thing, because all that they had in the church was obtained through great labors. And now the icons and vestments…

Finally the clergy and choir assembled in the center of the church, the parishioners took the banners and icons in their hands, and looked at one another with great anxiety. Only Vladyka John was calm; he had a concentrated, prayerful expression on his face, he did not betray the least concern, and did not answer the timid warnings. Already in those years he had such trust in God, and of course, clairvoyance.

They went out to the street with great tenseness and expectation, and began the procession. Only when they had finished the procession and returned to the church did the rain pour down with full force.

The occupation of Shanghai by the Japanese army

As early as 1937, after severe artillery preparation and aerial bombing, Japan, long coveting China’s nature resources, dropped its paratroopers around Shanghai. The Chinese army could not withstand the Japanese attack and the city was taken.

After occupying Shanghai the Japanese treated the Chinese very cruelly, but at first did not touch the foreign concessions, not wanting to complicate relations with England and France. From the White Russians they only demanded honor towards the Japanese. However the occupation’s relations with the Europeans became worse and worse.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked the American army base in Pearl Habor, and just a few hours after the attack the Japanese army based around Shanghai entered the International settlement. Very soon they interned the Europeans of those countries with which Japan was at war, making concentration camps for them.

During the occupation the Japanese built five camps: four for civilians and one for prisoners of war. The Vorobievs fortunately did not have to worry about the camps—the Japanese did not bother “White” emigrants because they were people without Soviet citizenship. But Natalia Vorobieva, Benya’s older sister did end up in a camp—she had married a Scotsman, and both she and her husband were interned by the Japanese.

Even the Japanese felt the power of Vladyka John of Shanghai

Vladyka always attentively followed the progression of the church services, and if someone read something improperly he would correct him. One day Benya saw that two Japanese officers were standing in the church next to Vladyka; they were in dress uniform, tall—apparently from the northern islands where people are taller. The boy noticed that the Japanese were carefully looking at the icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker. Even to the boy it was clear why they had come to St. Nicholas—this icon, which had earlier self-renewed, was very revered in Shanghai, and even Chinese and Japanese people venerated it.

Later Benya learned that in Japan there was once a mission headed by St. Nicholas of Japan, and he thought, perhaps these Japanese were parishioners of that mission?

Vladyka walked around Shanghai, visited the sick, communed the dying, and saved homeless children. He knew where to go, which corner of the city needed his help. Even before people had come to Vladyka he would already knew why they had come.

Once Bishop John had decided to check whether one church was intact, but shooting was going on in that part of the city. A patrol of Japanese soldiers were standing on the bridge. Vladyka explained to them that he wanted to go there and return, and they permitted him, giving orders to let him through. There was artillery cross-firing, but Vladyka walked tranquilly to the place where he need to go; and when he returned and walked past the Japanese, the officer ordered the soldiers to salute him—even the Japanese could feel his power. And Vladyka fearlessly went to many places where no one could ever expect him to go.

Alexander

Alexander’s older brother first became a businessman, travelled to Chinese villages, sold some wares, and then found work on a small English ship—two Russian guards defended the ship from pirates. Russians were highly valued as guards in those years in China; they were known for there bravery. Wealthy Chinese did not trust their compatriots and hired Russian bodyguards, knowing that former White Army officers who had promised to protect them would carry out their service not out of fear but out of conscience.

Natalia

Natalia and her Scottish husband ended up in a camp, where conditions where very hard. The prisoners were disgustingly fed—rotten vegetables and spoiled meat—and by the end of the war the disgusting quality of the food worsened. Whenever the Europeans protested the Japanese would answer that they were being fed better than the inhabitants of Japan themselves.

The camp prisoners often suffered from tuberculosis, malaria, and pulmonary-cardio deficiency, as well as beriberi due to the poor nourishment and lack of vitamins.

Throughout their time in the camp, Natalia and her husband were only allowed to see their relatives once. Then papa gave them some food products and vodka in a tin, which he had reclosed to look like new. The vodka could be used as medicine and antiseptic.

After the war, Natalia and her husband left for Scotland.

Nina

Once in the evening, someone timidly knocked at the home of the Vorobievs. When they opened the door, at the threshold stood a soaking wet, shivering from cold, young Italian. When they let him in he told them his story. During the war years the Italians were divided between the Hitler supporters and the antifascists. After Mussolini’s overthrow the Japanese considered the Italians to be traitors and treated them with greater cruelty in the camps than they did the other Europeans.

This young Italian named Tito served on a steamship, and his crew preferred to sink their vessel but not surrender it to the Japanese. The sailors themselves swam to shore and hid wherever they could. That is how Tito turned up at the Vorobievs. He was in danger of execution, and the compassionate Russians who risked their own safety gave him refuge in their garage next to the house, where he lived to the end of the war.

As it turned out later, it was no accident that the Lord brought the young man to the Vorobievs. He and Benya’s sister Nina fell in love and went to Vladyka John for a blessing to be married. Vladyka blessed them under the condition that Nina remain Orthodox, their children be baptized in the Orthodox faith, and they be raised by their mother as Orthodox Christians. That is how Nina married Tito in the Church, and they later left for Italy.

On the ship, Nina gave birth to her first son. When the ship docked at the harbor, her Italian mother-in-law, when she saw not only her son alive and well but also her newborn grandson, was beside herself with happiness. She wept for joy, pressing the infant to her breast and showing him to everyone proudly.

Vladyka John of Shanghai after the war

After the war a multitude of automobiles appeared in Shanghai. People would at times give Vladyka a car and he would travel to hospitals and prisons. Benya loved to ride with Vladyka in the automobile. The hospitals would let the boy in with Vladyka, but when Archbishop John would go to the prisons Benya would have to wait for him in the car.

Once the boy saw a cat in the hospital that he had also seen before, and he said to Vladyka, “That’s Vasya the cat!” Vladyka replied, “You mustn’t name give animals human names” [that is, the names of saints. Vasya is short for Vasily-Basil]. Benya remembered those words all his life.

Vladyka would make the rounds to all the sick; he knew with whom he should spend more time, whom he should bless, and for whom he should pray fervently.

Vladyka was by far not always given a car, and as he did before he would often walk to the hospitals, orphanages, and to sick people’s homes. Once Tito the Italian was driving rather far outside the city in an American company truck, in the direction of the airport. He saw Vladyka walking, alone, and so far from the city.

The Italian stopped his truck and offered Vladyka a ride. Vladyka stood and looked—such a tall truck, with high steps, and he was short of stature. How was he to climb in? Then the young, strong Tito carefully lifted Vladyka and placed him upon the truck step, and he sat in the cabin. When they arrived he jumped down himself.

Tito learned to his surprise and later told all the Vorobievs that on the outskirts of the city lived some completely impoverished Russians. They rented living space there because it was the least expensive. And Vladyka walked so far by foot, completely alone, and spiritually nourished these people. He himself knew who was sick and who needed to be visited, and for whom to pray.

A new danger

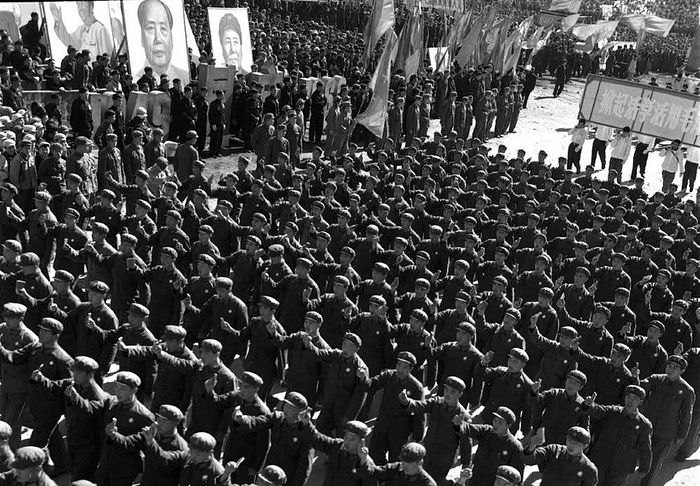

After the Japanese occupation the civil war began, and the six-million-strong Shanghai, the largest city in China, became the center of opposition between the Kuomintang—the nationalists under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek—and the communists of Mao Zedong.

The year 1949 was marked by the communist’s advance on Shanghai. A fearful atmosphere reigned everywhere, the police searched everyone they saw, people thronged the trains station ticket offices, and the trains departed packed to the gills; even a spot on the roof cost money.

Some Russians decided to return to the Soviet Union; they were assured that they would be able to choose a place to live in any city, but this was a lie—a large part of those who returned ended up in the camps.

In Shanghai there was an Association of Russian Emigration headed by the Enisei Cossak Gregory Kirillovich Bologov—a talented organizer and self-sacrificing, brave man. Vladyka John and Bologov spent much time trying to save the Russian refugees and the children’s home in Shanghai. Finally, with the help of the IRO (International Refugee Organization), which the refugees themselves jokingly called Aunt IRA, the Russians were given temporary shelter on the tiny Philippine island of Tubabao, three by four kilometers in size.

Father’s death and attack on his brother.

Of the Vorobiev family only his mother, Benya, and his brother’s wife with her little child set off for Tubabao. Nina had left with her Italian husband for Italy by then, and Natalia and her Scottish husband were in Scotland.

The death of their beloved father was a terrible blow. He had gone through the First World War and the Civil War, but he died at the hands of robbers. One day Benya returned home from school, and his mother was lying on the floor sobbing. The boy couldn’t understand what had happened, and his neighbors explained to him that his father had been killed. He was preparing for their departure to Tubabao and tried to exchange some possessions for cash, and was robbed and thrown into the river, where he was found later.

Benya’s brother Alexander was also attacked; they hit him on the head, robbed him and threw him into the river. When he came to he understood that he was being carried downstream. Death was near, but a steamship was passing by, and when he called for help they saw him and took him in. He worked for an English steamship company and later turned up in Australia. Later he brought his wife and child there from Tubabao.

The island of Tubabao

About 6000 Russians came to Tubabao. Thus did this uninhabited tropical island become the last refuge of the Russian Far East emigration!

Benjamin Vasilievich very well remembers that trip to Tubabao—he was fifteen years old. The ship captain was a Greek; many Russians, especially the elderly, lay seasick on the cots, while the children and teenagers ran around on the deck.

The climate on the island was totally unsuited to Russians—all year it was exhaustingly hot—around forty-five degrees (Celsius). The climate was especially hard on the weak, sick, and elderly.

The frequent rainfalls were followed by the scorching rays of tropical sun, and at night a dank coolness would descend upon tent city. In this climate diseases of the skin flared up immediately—people were attacked by pimples, abscesses, and boils. More serious and mortally dangerous were such diseases as tropical dengue fever, gastroenteritis, dysentery, and even tuberculosis. Clothing was spoiled and covered with mold.

He immediate felt better

Once Benjamin fell seriously ill—so ill that he lay in bed, and we all know how hard it is to keep a fifteen-year-old boy in his bed.

Suddenly, to his mother’s great amazement, into the tent with quick steps came Vladyka John. And it was not so easy to find the Vorobievs—a huge number of tents without numbers or addresses. Furthermore his mother had not told anyone about Benya’s illness. Vladyka entered and asked right away, “Where is Benjamin?”

Then he walked over to the cot and blessed the sick boy. The Vorobievs were very happy and surprised, and they didn’t know how Vladyka had found them. After his blessing Benya immediately felt better and very quickly recovered.

“His prayers protect you from danger

The locals never rushed to settle on Tubabao—the frequent typhoons there were a serious danger. Once the Russian heard over the radio that a powerful typhoon was heading their way. People were very frightened, but they heard later that the typhoon passed them by.

The local people said, “That Russian priest walks around the island and prays for you. His prayers protect you from danger.”

Vladyka’s prayer

It also happened with the rain on Tubabao as it did once in Shanghai. Benya worked in the tent kitchen helping the cooks, opening tins, carrying things. He found out that it would soon be a feast day and there will be a cross procession. Now on Tubabao it rained very often—a huge dark cloud closes in, there is a downpour as if the heavens were opening, and in fifteen minutes it’s over and steam is rising from the ground.

So the cross procession is about to begin and Benya is all ears, attentively watching what is happening—will the Shanghai story repeat itself, or will the downpour soak the procession? Everyone is anxiously exchanging glances; by all reckoning the cloudburst should come any minute. People are praying, singing, and Vladyka is calmly praying, seemingly paying no attention at all to the ominous dark cloud.

And as soon as the procession ended and the people entered the church there began a torrential downpour, as if waiting for the prayer to end.

Benya’s adventures in the jungle

It was very difficult for the elderly on Tubabao, but of course easier for the youngsters. They walked in the jungle and swam in the ocean. Benya would take some bread, go to the Filipinos, treat the locals, and they would give him a boat to take out. What more does a fifteen-year-old boy need?! Adventure! You float away and there is wind out there, the current takes you away from the shore, and you have to figure out how to get back to the island!

Once Benya was running barefoot in the jungle when he saw a snake, not just slithering along the ground but with its head up vertical. The boy was frightened, but he and the snake parted ways peacefully.

There were lots of iguanas. If you just happen to see this monster lizard you can have a start. One family raised chickens; well, an iguana caught one hen—and that was the end of that hen!

Once again Benya was walking in the jungle and he saw a spot with some nice warm water, not too deep. He thought, I’ll just wet my feet in that water. No sooner had he stepped foot when something very much like a crocodile leapt out! Benya jumped out of the water and made tracks.

Benya’s adventures in the ocean

Benya really loved to swim. The water in the ocean is so warm and pleasant. Red corals, and you can stand on them as the beautiful little fish swim right up to you and nibble your feet. But you had to be careful with the corals—they are very sharp and you can cut yourself. Once Benya was swimming under the pontoon bridge and cut himself so badly on the coral that he had to be hospitalized.

Another incident. One girl caught Benya’s eye and he decided to dive into the water, swim over to her and grab her leg to scare her. The usual boyish trick. He dove in but made an awkward turn, then felt something wrong with his neck. He forgot all about the girl, climbed out as best he could and lay on the pontoon bridge. As it turned out, when he dove he turned his neck and damaged his neck vertebrae. He felt worse and worse, just lying there unable to move.

Next to the pontoon some Filipinos were driving in a car, and the swimmers asked them to take the boy to the hospital. They took him to the doctors, who told him to lie still and not move.

A friend was diving with Benya, and he was mute. His friend left off swimming and went to the camp to Benya’s mother, showing her with hand signals that her son had hurt his neck. He showed her so graphically that Benya’s mother was frightened half to death, and ran off in a panic to the hospital.

But Benya lay in bed for a day or two and it all went away—he was young, and healed quickly.

Captives on a tropical island

The Russian refugees weakened from the heat and tropical diseases. The four months that the IRO had negotiated with the Philippine government had ended, but there wasn’t a country that was ready to take in the Russians. All told they lived around three years on the island instead of a few months.

The Australians gave visas, but only to young, strong men ready for hard physical labor. The French were only interested in Russians who had relatives or close friends in France. The Paraguayans recruited refugees from Tubabao for work on the plantations and jungles. A portion of the Russians also left the island for South America: to the Dominican Republic, Chili, and Surinam.

Vladyka John appeared before the Senate judicial committee in the U.S.A. and described the critical situations of the refugees. He also made the acquaintance of California senator William Noland and told him about the Russian refugees. The senator came to the island. Interesting—who did he expect to see on the formerly uninhabited island of Tubabao? Savages? But the Russians dressed in suits and met him like normal, civilized people. The senator talked with them and came to the conclusion that they are not communists but decent gentlemen. It was perfectly all right to invite them to America.

Prayer that opened all closed doors

The Americans agreed to give visas to anyone who could find a sponsor that was an American citizen and would guarantee that the new arrival would have work and a place to live. Most often it was impossible to find such a sponsor. Moreover the Americans decided that the Russian children who were born in China would be considered Chinese citizens. So Benya, like all the other young Russians, was considered a Chinese citizen, and the quota for the Chinese was already filled; he would have to wait eight years to receive a visa.

These Russians boys and girls had no money, no sponsors, but they had something much better than that—the fervent prayer of their spiritual guide, Vladyka John of Shanghai, who opened all closed doors.

This prayer achieved the impossible. In April of 1950, the U.S. Congress approved an amendment to the law on quotas for emigrants, allowing an extra-quota entry into the U.S. for Russians from Tubabao. But a little time had to pass before the amendment would come into force. And finally the Russian refugees found themselves in America.

Benya and his mother, Evgneia Polycarpovna, settled in San Francisco, next to the old cathedral.

So, that is how the Russian Diaspora turned out for the Vorobiev family: Nina with her family in Italy, Natalia and her family in Scottland, Alexander and his family in Australia, and Benjamin and his mother in California.

This was God’s Providence for the Russian refugees: They dispersed to all corners of the earth and brought with them the Orthodox faith.

How a mother’s prayer and Vladyka’s intercession saved Benya

Benya went to school; he knew English from his early years since he studied in the Joan d’Arc private school in Shanghai. Then the youth got a job, and his first job was completely unskilled: he worked as a busboy in a restaurant.

There was an amazing story about Benya. He saved his money and bought a motorcycle. Happy as a lark, he set out to visit his friend in Santa Barbara. This friend had offered him a job at a construction site, and Benya agreed to it, because they promised good wages while the restaurant pay was miserable.

He returned from his friend on wings, filled with impressions and hope, but very tired. His eyes began to close and for a minute he fell asleep. Then he heard his mother’s voice—his mother was talking with him. He couldn’t understand how his mother had gotten there. Wasn’t she supposed to be at home?

He came to himself, stopped his motorcycle, laid down on the grass in the dark, thinking that he was on the roadside, and fell asleep. When he woke up the next morning he discovered that at night he had gone off the road and was driving amidst the trees. This was a real miracle that he did not run into a tree and crash.

When he arrived home he learned that his mother didn’t sleep all night and was praying for him, turning for help in prayer to Vladyka John. Her mother’s prayers and Vladyka’s intercession had saved the young man.

Chief engineer for bridge construction in California

Benya went to work at the construction site, and then went to study engineering and construction. He was married and had a son, and his son also went to university. Now he has a growing daughter—Benjamin Vasilievich’s granddaughter.

But Benjamin Vasilievich himself became the chief engineer for the construction of bridges in the California Department of Transportation. And many of the bridges that we crossed from Los Angeles to San Diego and Mexico were built under his management.