This discussion of the word “prelest” was taken from a question and answer session with Professor Alexei Ilyich Osipov of the Moscow Theological Academy in Sergiev Posad.

* * *

What is prelest?1 It is lest [Russian for “flattery”] taken to the highest degree. We can flatter someone else, we can flatter ourselves; that is we not only can, but do flatter ourselves. What does it mean when we say, “I flatter myself?” It is not in the sense that I try convince myself that I am so good, that I am the best in the world. No, you don’t even need to convince me, I know that I am good. And it’s not at all important to me if someone criticizes me for something; that person is simply a fool, he simply doesn’t understand that I am good. That’s what it’s all about! Well, there are stupid people, it’s true. Who is stupid? The one who criticizes me. He doesn’t appreciate that I am the best in the world.

You know, it’s interesting—I really do see that I make mistakes, that sometimes I do things wrong; but nevertheless I feel that I am good. How interesting! I am good, and this feeling is invincible in me. That is the level on which I live.

But I decided to do more that even I do now; I, as a Christian, will begin to labor in asceticism. I will not just read morning prayers, but add 100, 200, 300 Jesus prayers. I’ll read the Psalter in the afternoon, an Akathist. I’ll start going to church more often, and so on. I’ll do much more.

And if I don’t understand what is going on at this point, then my “I”, which I so strongly feel is the best in the world, begins to rise like leavened dough. I begin to feel that I am not only good, but righteous, a saint. Moreover I can start having unusual dreams, even visions, and delightful states, etc.

Prelest is that state in which a person sees himself as a saint. Perfect. Worthy of God, worthy of all God’s gifts—that’s what prelest is.

This is why it’s called “prelest”—because flattery, self-flattery is essentially present in all of us. Here a person has, or so it seems to him, labored, and through his own labors has attained very much, acquired very much—and he falls into prelest.

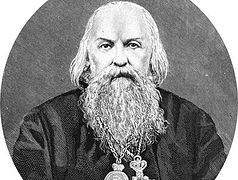

In this state, prelest is often joined with a very interesting state of the body. For example, St. Ignatius (Brianchininov) writes how once a monk came to visit him in St. Petersburg from Mt. Athos. It was winter, freezing cold, but the monk was dressed only in a cassock and sandals.

“Aren’t you cold?

“No, not in the least.”

And the monk barely ate anything. “Aren’t you hungry?”

“No, not in the least.”

St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov), a rare genius, used the Socratic method… Did you know that Socrates never tried to convince anyone? He always asked questions, but asked them in such a way that the other person could not find a way out. Shall we cite an example before going on about Brianchaninov? Socrates asked one sophist, “Hippios, I hear that you are a very smart man. Is that true?”

“I swear by the dog, Socrates, you are right.”

Swearing by the dog in those days was the highest possible oath! For some reason “dog” today is derogatory. But a dog is the most loyal being. Hippios was elated—Socrates was telling him that he is a smart man! And his disciples were all standing around.

“Well then, Hippios, here is why I am asking you.”

“Yes, Socrates, what do you want?”

“Tell me, Hippios, what is beauty?”

“Socrates, don’t you understand? Well, a beautiful horse… you know?”

“No, Hippios, I am not asking about horses.”

“Well, a beautiful woman…”

“Hippios, don’t you understand that the greatest beauty in the world for the goddess is the monkey? I am asking you, what is beauty?”

“Well, Socrates, you want something that I don’t understand…”

There was all-around laughter. Hippios the “sage” left in shame, ran away… Incidentally, that is why Socrates didn’t like all of those sophists.

So, Ignatius (Branchininov), using Socrates’s method, asked this Mt. Athos monk, “Hey, how did you attain to that? That would be great for me too; I would not need any clothing. I am always wearing a fur coat. And if I could just eat less… Ignatius (Brianchaninov) goes on about all this. The Athonite monk starts heatedly explaining to him how he had to pray, and what he needs to do: “Pray, place yourself before the Lord God, Christ Himself—you need to pray to him with fervor!”

“What should I pray about?”

“That the Lord would grant you this, or that…”

“But what about sins?”

“Well of course about sins… Oh, leave me alone…”

Then St. Ignatius said to the monk, “I of course don’t understand these questions, but you there on Mt. Athos know everything. This is St. Petersburg, you know, worldly life… But I read in St. Isaac the Syrian and Abba Dorotheus—you, know, those holy fathers—they write that we have to pray this way…” And he told him how. “I myself am in no condition to try to pray like that—I am the abbot of a monastery. But perhaps you can try?”

“Well, alright, I’ll try.”

About three weeks go by, or a month, and that monk again comes to visit St. Ignatius. And St. Ignatius says to him, “You will be staying in the guesthouse. I would advise you to stay on the first floor.”

“Why?”

“Well, just in case. What if angels suddenly come to carry you away?”

“You know, Fr. Archimandrite, that’s true! I’ve had those very visions when angels wanted to carry me away, straight to Mt. Athos…”

“Yes, that is why I’m telling you this. What if angels take you up and accidentally drop you somewhere along the way? It’s better that you stay on the first floor.”

A month later that monk again appears at St. Ignatius’s door in a rage. “What have you done to me?”

He arrived in a fur coat, felt boots, and said that he had begun getting cold and eating a lot. “I prayed like you taught me, and now I can’t do what I did before.” In general he was fit to be tied.

Well, you can see the fruits of prelest. It turns out that there is true prayer, and there is false prayer. That is apparently how it is. There is the right way, which leads a person to where he begins to see himself. And there is the opposite way, which tends to cover a person’s true self, and he no longer sees anything wrong with himself—no inadequacies, no mistakes; he sees only total holiness. That is prelest. It is often accompanied by sensations of a physical nature, as you can see by the above example.

There is a modern-day Athonite, Monk Charlampios, who suggested to a young man that he start right off with saying 14.5 thousand Jesus prayers loudly, quickly, and distinctly, so that “the demons would not jump through the words of the prayer.” His tongue hammered l away like a motor. And when this young man who had never done anything like this before had drummed away for four hours, he felt a sweetness in his mouth everywhere he went. His elder Charlampios was ecstatic. “Only four hours and you’ve already acquired grace! Others spend years, decades, and now everything’s alright with you—you need nothing more.” This is a false path.

Prelest is a state that brings a person to self-opinion, and to this state of prelest leads a false, wrong path—first of all prayer without understanding that the first sign of a healthy soul is when it sees its sinfulness, which naturally exists in us. And if I don’t see this, it means that I am blind.

That is what prelest is, if you want to know briefly. Again I would strongly advise you to have nearby, at least have on your bookshelf, the works of St. Ignatius (Brianchinov).2 His Patristic Writings, with passages from the holy fathers and even brief stories, are very interesting. Also his letters to various people, to military officers as well as poets and composers including M. I. Glinka are extraordinarily interesting. These readings are a must.