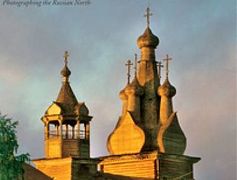

Prof. William Brumfield. Photo by Rusroads.com

Prof. William Brumfield. Photo by Rusroads.com

William Craft Brumfield is a professor of Slavic Studies at Tulane University, a Russian architecture historian, a specialist in local history, a photographer, and the organizer of the first exhibition of Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorsky’s (1863-1944) photographs at the Library of Congress in 1986. In Brumfield’s view, the exhibition helped many people rid themselves of negative stereotypes about Russia. The exhibition of Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs was held thanks to, among other things, the photographs and books on Russia by William himself. “It was a breakthrough!” Brumfield says with pleasure, “You could even say a furor. I love such furors!”

We spoke with the professor on the mastery of Prokudin-Gorsky’s, who offers through his photographs a portrait of the “serene and happy times of Russia’s past” that many Russians pine for today, thinking that Russia has lost its power for good. “You must not lose heart and become despondent,” the American slavist says, “but you should continue working peacefully and with love.”

“You haven’t lost Russia!”

Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorsky —William, we have before us these wonderful photographs taken by Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorsky during his travels across the Russian Empire. Looking at them, honestly, I have mixed feelings of delight mixed with resentment and bitterness at the same time. So much was lost and barbarously destroyed… We have lost our Russia!

Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorsky —William, we have before us these wonderful photographs taken by Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorsky during his travels across the Russian Empire. Looking at them, honestly, I have mixed feelings of delight mixed with resentment and bitterness at the same time. So much was lost and barbarously destroyed… We have lost our Russia!

—Please! You haven’t lost Russia! I should begin not with Sergei Mikhailovich but with the excellent film director and Orthodox Christian Stanislav Sergeevich Govorukhin, the author of the movie and book The Russia We Lost, who died not long ago. On the one hand, I respect Stanislav Sergeevich very much and wholeheartedly share his pain for his fatherland. On the other hand, on the basis of my own fifty years of experience of discovering Russia, I must disagree with his opinion and your sorrow. I believe there is no reason to be discouraged because it is too early to “bury” Russia; it is still a great country and civilization.

True, there are losses, and it’s really terrible and sad. There are many reasons. Prokudin-Gorsky of course believed in the empire, and he showed in his photographs how it developed, becoming more powerful year by year. He captured the whole of the great country in his lens, both its central regions and borderlands; for example, let us recall his images from Turkestan,[1] for example his Emir of Bukhara, inmates of a Turkestan prison, the joyless life of many peasants – he was an honest man and would portray the reality quite objectively. While believing in the empire, this master had no religious feelings for the earthly form of government. In my view, he was an impartial chronicler of that era. He both loved and esteemed his motherland and his fellow-countrymen, yet he, like St. Nestor the Chronicler before him, did not conceal the challenges facing Russia and its people. He shows them honestly. Only, instead of pen and parchment in hand, he had a camera—a result of his work as an engineer and inventor

Warm melancholy instead of black despondency

—What is the significance of Prokudin-Gorsky’s contribution to world culture, in your opinion?

—Prokudin-Gorsky is a great, significant phenomenon in world photography. He created a whole world, and technology enabled him to do so. He took the camera designed by Adolf Miethe, upgraded it, and then by use of color showed his contemporaries and progeny the times with all its charms and faults. As we remember, Prokudin-Gorsky’s project was aimed not only at capturing the monuments of antiquity, but also people of a wide range of ranks and social strata and nature and landscapes.

A view of the city of Tobolsk from the northwest side of the Dormition Cathedral

A view of the city of Tobolsk from the northwest side of the Dormition Cathedral

Truly, he created an empire, and people looking at his photographs see that period as an idyll—a bright idyll of the good past. In my view, it’s nostalgia: We look at these amazing colors and think, “Oh, how nice!”

Torzhok. The Transfiguration Cathedral (to the right) and the Church of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem

Torzhok. The Transfiguration Cathedral (to the right) and the Church of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem

Perhaps we look at old black-and-white photographs of our relatives or ourselves with the same feelings, remembering the “good old days.” Yes, nostalgia is an inherent part of our lives. It can also be said that if we have nostalgia—that is, a bright sadness for the “good old days”, when we see our old family photographs and those by Prokudin-Gorsky alike, it means that we perceive Russia in a familial manner. Therefore, the family bonds with “mother Russia” are still quite strong, and it gives me, I think, the right to say that all is far from lost.

—So, you mean to say that this master gives us the opportunity to feel proud of our fatherland and see an example just as we see our great-grandfathers, grandfathers, and fathers as our role models?

—Exactly. But also, he gives us an opportunity to reflect on the reasons for the tragedy of Russia in the twentieth century. In truth, the ensuing decades were the most terrible and full of trials, such as wars, revolutions, “dispossession of kulaks [peasants wealthy enough to own a farm and hire labor—Trans,]”, new wars, and “perestroika.” But it seems to me the country has outgrown, withstood, and survived them all. I can explain it only by the help of God. The people tackled these trials and tribulations by their heroism in wars, self-sacrifice, herculean labors, and outstanding cultural and scientific achievements, and we have no right to deny all of this.

Three Generations. A.P. Kalganov with his son and granddaughter. The latter two work in the workshops of the Zlatoust plant. Autumn 1909

Three Generations. A.P. Kalganov with his son and granddaughter. The latter two work in the workshops of the Zlatoust plant. Autumn 1909

—But the best sons of the country, the “cream of the crop” were annihilated at that time.

—Thank God, not everyone. We should bear in mind that each “social stratum” has its best and worst representatives, who are its pride and its shame. Do you want an example? Peter Ermakov (who, by the way, had graduated from an Orthodox parochial school), one of the executioners of the holy Royal Martyrs, used to brag that he had been actively involved in the Royal Family’s brutal execution. Isn’t it awful and loathsome?

—Definitely. But let us recall what the great military commander Marshal George Konstantinovich Zhukov said to Ermakov during his time in then-Sverdlovsk when he held out his hand to the marshal, intending to “share” his memories with him. Zhukov rebuffed him with disgust and said, “I don’t shake hands with butchers.”

—This story proves that I am right. As you can see, the “cream of the crop” survived.

Photography as a reason to pray

—As you say, in Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs you can feel not only a feeling of pride in your country but also concern. And many great people, holy bishops, writers, and so on, felt this concern too.

—If you take the Ermakovs, the Yurovskys, and others, Feodor Dostoevsky foresaw all of this so precisely. It is enough to read his truly prophetic novel Demons to see this. Dostoevsky was a contemporary of Prokudin-Gorsky, and I think both were unprejudiced chroniclers who suffered and prayed for Russia: The former expressed his thoughts on paper, the latter on photoplates. Perhaps it would be fair to say that both in the photographs of Sergei Mikhailovich and in the novels of Feodor Mikhailovich one can see an admiration for Russia and the soul of Russian people as well as a deep concern for it. The artistic devices of both of them are wonderful, yet they portrayed much more than “ceremonial,” “formal” things that enrapture bureaucrats and nobody else.

It is also interesting that Sergei Mikhailovich’s bright yet sorrowful look on Russia was, in my opinion, directed towards the future. If you look at his 1911 photograph depicting children at the dam near Belozersk, you will see an old, ramshackle church behind them. Perhaps he tried to imagine and called on us to think about what would become of these children. Perhaps there is a reason here for prayer for them and for Russia.

A group of children. Belozersk. 1909

A group of children. Belozersk. 1909

—But don’t we have a reason to pray now, a hundred years later?

—We do, but it’s already a hundred years later. Our prayer will probably be different. Famine, devastation, civil strife, war, persecutions—what became of these children, these pure souls? Who did they become? Did they languish in labor camps or stand guard in their watchtowers? Did they leave Russia or remain with their homeland? Did they write their names on Reichstag or develop satellites? Prokudin-Gorsky gives us the widest scope for reflection. And I concede that the master, like Govorukhin a hundred years later, spoke about the Russia that we lost, calling on his contemporaries not to forget the most essential part of Russia, namely Holy Rus’.

Breaking stereotypes in an American style

Boats on the bank of Lake Onega

Boats on the bank of Lake Onega

—Did Prokudin-Gorsky’s work have any influence on you as a photography?

—From a technical point of view it didn’t. I knew virtually nothing about him for many years. It was not until 1985 that I discovered this treasure he left behind. Not long before, my book, Gold in Azure: 1,000 Years of Russian Architecture, had been published. It was the first comprehensive study of Russian architecture in the West. It produced something like a furor: It turns out Russia is a country with ancient cultural traditions, and the stereotypes and labels pinned on it over the course of several centuries are simply incompatible. The stereotypes were broken. The Library of Congress invited me to organize the first exhibition of Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs.

A settler’s family. Grafovka Village. 1912

A settler’s family. Grafovka Village. 1912

Sergei Mikhailovich showed his photos on a screen by a special projector and also published some of his photographs during his lifetime. But there was no collection of color prints, so it was extremely difficult to print them and I had to work with black-and-white negatives. An incredibly hard work! I’ll tell you a little secret: We took the color of bark of trees as our reference point as it was the most natural color according to experts; after that we selected all the other colors.

The results were very interesting. It coincided with the preparation for my own exhibition dedicated to Russia. So our lives are intertwined with one another. I worked with Sergei Mikhailovich’s originals and organized the first exhibition of his photographs which opened in the fall of 1986. Then I wrote a small brochure, an article for a science journal, and thousands of Americans saw the masterpieces of this Russian master over the period of several years. I am certain that this impelled many of them to seek to better understand Russia.

When I familiarized myself with Prokudin-Gorsky’s work, I realized that we are like-minded persons. It is important to look at the world and your homeland with kind eyes, to worry about it, to love it, and to oppose any slander.

—You must have endured a great deal of trouble for your aspiration.

—Oh yes! Many of my colleagues advised me with disgust: “Mind your own beeswax! Don’t get into photography and architecture if you’re such a slavist. And anyways, you know, Russia...” The academic world is very challenging. As the psalm says: Eyes have they, but they see not (Ps. 135:16). And now, with this latest political coolness, they’re singing the same old song again.

No sugariness, please!

A group of people standing by a natural spring at the health resort in Borjomi

A group of people standing by a natural spring at the health resort in Borjomi

—But let us return to the light. What feelings do our master’s photographs evoke when you look at them?

—His photographs are mystical in the good sense of the word. A joyous light is often seen in them! He showed a spiritual through color. Few people have such striking abilities. There are significant parallels with iconographers: You have to have a kind heart to paint a good icon. Sergei Mikhailovich is a unique photographer in the history of world photography. He is the only master to create a whole world.

A curved track near the Vyazovaya railway station. September 12, 1909

A curved track near the Vyazovaya railway station. September 12, 1909

—But it is not a fictitious world, invented by a “sickly sweet” imagination. It’s not just “smells and bells.”

—Certainly not. What you’ve mentioned is often a result of our own fantasies and personal interpretations. I repeat: Prokudin-Gorsky’s images are not some cheap prints, not bleeding-heart fantasies, but a reflection of that reality with all its pluses and minuses. As true works of art they make a viewer think not only about aesthetics… Take for exaple the photograph of the railway in the Ural Mountains of the Chelyabinsk region: a sense of silence, the power of nature, a lone railway line… A sense of silence, perhaps remoteness, but by no means gloom, loneliness or abandonment.

We live in the world that Prokudin-Gorsky saw and showed to us. He couldn’t care less about sentimentality. Take his photographs of peasants. They are bright people, but bereft of any idyll: You can see their poverty, misery, and even apprehension. And what about the images of the Austrian prisoners of war building canals in the Vologda region? They don’t care about “romanticism!”

Austrian prisoners of war by the barracks

Austrian prisoners of war by the barracks

I was happy to discover his works. By that time I had worked in Russia for many years, knowing many photographers, writers, and architects—the “cream of the crop” that was never totally destroyed.

—Prokudin-Gorsky was not the only good photographer of his time.

—Nevertheless, he was very unique. There were many English photographers who worked hard both in England and in British colonies trying to create an image of the “English world,” but unsuccessfully. Meanwhile, Prokudin-Gorsky succeeded in portraying the Russian world. Russia is one organism which cannot be divided into atoms. True, there are multiple ethnicities, languages, and cultures in it, and ideally all of them constitute a whole. I repeat: ideally.

For instance, take his images of Turkestan. These are amazing photographs of Russian settlers who moved there during the tenure of Pyotr Stolypin. By the way, Prokudin-Gorsky’s project was largely inspired by Pyotr Arkadievich who planned to purchase his photographs, but was assassinated in 1911.

Unfortunately, in 1916 there was an uprising in Turkestan that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of settlers and representatives of local ethnic groups.

And what about the starving inmates of a Bukhara prison and the triumphant Emir of Bukhara? Isn’t it an objective view of the time? So the master’s photographs are a very powerful and extensive documentary resource.

Dirt and exotic pearls

—From time to time I still meet people with cameras and video cameras in their hands traveling across Russia and trying to capture its “alcoholics, garbage dumps, and desolation.” Germans and Americans especially did this for some reason. Unfortunately, today most of them are Russians and Ukrainians… Can we advise such garbage dwellers to familiarize themselves with the works of Prokudin-Gorsky to learn from him the ability to view the world through a kind lens and not to judge everybody and everything?

—No. You can do it, but it will be casting pearls before swine. There’s no point. Those who want to see and have the ability to find good things and those who prefer to rummage in trash have absolutely different goals and desires.

—Your words are in keeping with the Gospel: A good man out of the good treasure of his heart bringeth forth that which is good; and an evil man out of the evil treasure of his heart bringeth forth that which is evil: for of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaketh (Lk. 6:45).

—Exactly! The same is true of cameras and video cameras, not only of mouths. You will see a legion of such individuals on TV and the internet. Let’s hope they’ll eventually come to their senses.

Self-portrait. Kivach Waterfall, Olonets Province

Self-portrait. Kivach Waterfall, Olonets Province

And, sadly, in an environment like this, Prokudin-Gorsky is exotic. I firmly believe that familiarity with Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs (not just a superficial glance) would be a great help to all who want to get to know Russia at least a little better and more sincerely—better than television, blogs, and newspapers. Bear in mind that nostalgia for the “good old days” should motivate us to work for the good of Russia and pray for it instead of plunging us into deep despondency.