This homily was delivered at St. Tikhon’s Monastery in South Canaan, Pennsylvania on the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God, August 15, 2018. It was annotated and somewhat expanded for this publication.

O glorious Virgin Mother of God, how can I—indeed, how can anyone—speak about what has come to pass this day? What can I say, O Queen of Heaven, about this passing-over of your soul from death unto life, about this pascha of your body from the grave to the Heaven of Heavens? Where, most pure Lady, where can I find words that befit the mystery of your exodus from this world to the life of the age to come?

We find the answer to these questions, brothers and sisters, in the same way that we find the ultimate answer to every question: By fixing our gaze on the Lord Jesus Christ. We look to Christ. Let us look to the Son that we might better understand the mother.

Not long ago, dear friends, we beheld Christ on Mount Tabor, transfigured in glory and light, and we, with the apostles Peter, James, and John, saw Moses and Elijah speaking with him.[1] What were they talking about on that occasion? St. Luke tells us that they spoke about his exodus, which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem (Lk. 9:31). That is to say, they were speaking about Christ’s approaching death and resurrection. Christ’s “exodus”: Moses was the one who had led God’s people in the Exodus—their passing-over from slavery in Egypt to the blessed life of the Promised Land, whereas Christ, the true Pascha, had come to liberate us from slavery to the devil and all his works and bring us into the freedom of life in the Kingdom.

The prophet Elijah was the one who didn’t die but was taken up from the earth in a fiery chariot, to go dwell on high;[2] but Christ was the one who was to go down to death, who was to taste of this death of which Elijah himself had not yet tasted. And I think Christ may have spoken with Elijah about his coming resurrection from the dead and about his Ascension into Heaven. For indeed, Christ, with his human flesh and blood, was to ascend higher than Elijah had ascended. Elijah’s fiery chariot only took him so far: The Scriptures tell us that Elijah was taken only “as though” into Heaven.[3] But Christ ascended to the very pinnacle of Heaven. Christ, who in his Divine nature was never parted from the bosom of the Father, now, in his human nature, was to be seated on the throne of God (cf. Eph. 1:20–23).

And why? Why did Christ do all this? We know why from his own words: I go to prepare a place for you, so that where I am, you may be also (Jn. 14:2). A place for you. On a different occasion He gave a similar promise to His disciples when He said, To him who conquers, I will grant him to sit with me on my throne, as I myself conquered and sat down with my Father on his throne” (Rev. 3:21).

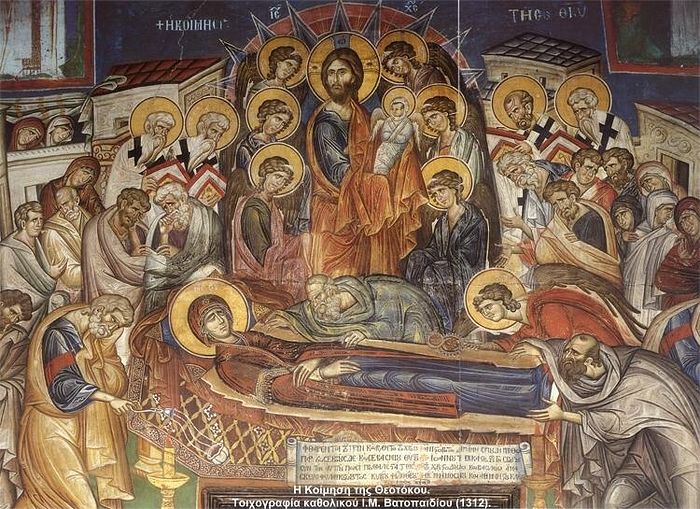

And today we see these promises fulfilled. Christ went and prepared a place for his mother, who was His closest and most perfect disciple,[4] and he has seated her with him on his throne—he has co-enthroned her with himself. She who had been the closest witness of his Passion and death (Jn. 19:25), has now herself passed through death to become the closest, and indeed the first, human witness of his surpassing glory and excellency.[5]

On Golgotha, that sword that Simeon had foretold (Lk. 2:35) passed through her soul, just as the spear passed through the side of her crucified Son (Jn. 19:35). And by the grace that came from the blood that was shed on Calvary, Christ has made a way for us to enter into the Holy of Holies. By his flesh that was pierced open for us as he hung on the Cross, Christ has opened for us the way into the very heart of God (cf. Heb. 10:20). By his flesh, Heaven is thrown open; by his blood, we who are flesh and blood are invited to take our place there on the throne of God.

But how does God come to have flesh and blood? We are created, formed from the dust of the earth. He is uncreated, and there is no word or thought of man or angel that can suffice to express the boundlessness of his Godhead. Yet, as we heard in this morning’s Epistle reading from St. Paul, he did not view being equal with God as something he had to try to hold on to. Instead, he took upon himself the form of a slave (cf. Phil. 2:6–7).

And now we see him in his own person lifting up our clay into Heaven. How? How did the eternal God, who is by nature pure spirit, come to share in our flesh and blood? He did so by receiving it as a free gift from one of his own creatures. He partook of human nature by becoming the son of a woman he himself had created. He united himself to flesh and blood in the womb of her whom we celebrate today in glory, in the womb of Mary—Mary, whose holiness and purity makes even the angels, even the cherubim and seraphim, marvel in dumfounded silence.[6] It was her flesh, it was her blood, freely given to him, that opened for us the way into the holy place of God. It is the fruit of her womb that has entered for us beyond the veil to prepare for us a place and a throne. “He made thy body into a throne, and thy womb he made more spacious than the Heavens.”[7] God was enthroned in Mary, and now Mary is enthroned in God. Her womb contained Heaven. Now Heaven contains her.

And not just her soul; her body as well.[8] That particular body that had given birth to Life itself could not remain very long in the tomb of the dead.[9] One of the Church’s readings for today’s feast puts it like this—and I think this is worth quoting at some length:

Conforming in all things to Christ our Savior, the most holy Virgin followed all the paths trodden by Christ to spread sanctification throughout our nature. After following him in his Passion and seeing his Resurrection, she now had the experience of death. As soon as she was parted from the body, her most pure soul found itself united with divine Light; and her body, having lain a short time in the earth, was soon raised by the grace of the risen Christ.

This ‘spiritual body’ [1 Cor. 15:44] was received into heaven as the tabernacle of God-become-Man, as the throne of God. It is the most significant part of the Body of Christ, and has often been likened by the holy Fathers to the Church itself, the dwelling-place of God among men, the first-fruits of our future state.[10]

Note in particular that last phrase: “the first-fruits of our future state.” This is an important point. This special gift of bodily resurrection which the Holy Virgin received just three days after death is the same resurrection which your body and my body—and all those bodies buried outside in our cemetery and, indeed, throughout the whole world—will undergo at the Second Coming of Christ, at the last trumpet (cf. 1 Cor. 15:52).

So, our Lady has gone on ahead of us, both in soul and body, and by the translation of her most pure body from the grave to the throne of the Godhead, she has confirmed for us the Resurrection of her Son, as well as the future resurrection of us all.[11]

Meanwhile, she is not idle. In this in-between period between Christ’s first coming and His second coming, she has much work to do. And her work now, as the Queen of Heaven, is similar in character to what her work had been on earth. It’s not Martha’s work of outward productivity and business; it’s Mary’s work of inward attentiveness, the interior work of the heart.[12]

She kept all these things in her heart. St. Luke tells us this twice: Everything having to do with her Son was stored up in the spiritual treasure-house, in the interior sanctuary of Mary’s heart. And what that means, among other things, is that she carries in her heart all the members of the Body of her Son: every person who has been united to Christ, who has put on Christ: she is their Mother, because she is Christ’s Mother.[13] She is our Mother, because we are “in Christ” (cf. Rom. 12:5). And that means that she bears you and me in her heart as she stands in prayer to God. She’s praying for us; she’s interceding for us; and, indeed, we can boldly say that in Christ she is mediating for us.[14] And what is her prayer on our behalf? It is that now in this age we will live our lives in such a way that when the time comes for us to rise from the grave, when our soul is re-united with our body, it will be for us not a resurrection unto condemnation (Jn. 5:29), but instead a resurrection unto eternal and abundant life. Amen.

***

Fr. Herman is a member of the brotherhood of St. Tikhon's Monastery in South Canaan, Pennsylvania, and a liturgical editor for St. Tikhon's Monastery Press. Fr. Herman also lectures in Spirituality and Liturgics at St. Tikhon’s Seminary and taught liturgical music at St. Vladimir’s Seminary in New York for several years. His twelve-part video series that introduces the Typikon to chanters, choir directors, and readers can be found beginning here and here.