Why do we know so little about Anna the Mother of the Most Holy Theotokos, and why does the Church venerate her? Foma.ru correspondent Sergei Milov asked the linguist and Bible scholar, docent of the Institute of Eastern cultures and antiquities of the Russian State Humanitarian University, head of the Sts. Cyril and Methodius department of Bible studies of the Church Masters and Doctoral programs, Mikhail Georgievich Seleznev.

—Mikhail Georgievich, why doesn’t the Bible tell us anything about Righteous Anna?

—The fact is that the texts of early Christian literature take very little interest in general in the daily details of their heroes’ lives, their actions or their family relationships. The Gospels even speak very sparingly about the childhood of Jesus. The Gospel of St. Mark begins with the Lord’s Baptism, and the Gospel of St. John, after a prologue on the Logos, also goes straight to the Baptism. As for the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, there are stories from Jesus’s birth and childhood. However these stories were written not in order to inform us about some additional details of daily life, but for the sake of these texts’ symbolic weight. For example, Matthew presents Christ’s ancestry in order to connect the Old Testament story with the New Testament. The evangelists took little interest in the simple, ordinary details (for example, what Jesus looked like, the color of his eyes and hair).

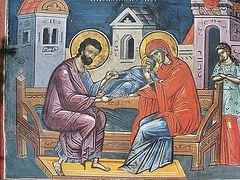

The meeting of Righteous Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gates. 16th c. The early Christians had the feeling that the end of the world was near, that it could come any day, and therefore historical details of everyday things were not important to them. What was important was that a new era, and new world was about to begin. This is what was in the center of attention of the first generation of Christians. The apostle Paul experienced his conversion in Damascus; people were still alive who had seen Christ. He could have gone to them and asked them about everything more particularly (as any of us would do if given the chance!). But the Lord’s appearance to him was enough for the apostle Paul; he did not go to the apostles who knew Christ in His earthly life to ask about this; he did not go and ask people made of “flesh and blood” to learn the details of Christ’s life (Gal. 1:15–17)… This was not important to him.

The meeting of Righteous Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gates. 16th c. The early Christians had the feeling that the end of the world was near, that it could come any day, and therefore historical details of everyday things were not important to them. What was important was that a new era, and new world was about to begin. This is what was in the center of attention of the first generation of Christians. The apostle Paul experienced his conversion in Damascus; people were still alive who had seen Christ. He could have gone to them and asked them about everything more particularly (as any of us would do if given the chance!). But the Lord’s appearance to him was enough for the apostle Paul; he did not go to the apostles who knew Christ in His earthly life to ask about this; he did not go and ask people made of “flesh and blood” to learn the details of Christ’s life (Gal. 1:15–17)… This was not important to him.

—And how should we relate to the fact that the information on the life of Righteous Anna is taken mainly from early Christian apocrypha?

—When decades and more had passed after Jesus’s life, the end of the world was no longer looked at as a close reality; it was postponed to an imprecise future. Then interest grew in the events with which Christianity began, to the tiniest details of how those people spoken of in the Gospels lived. But the era of Jesus Christ had by then had become the past, to which no one could return to ask eyewitnesses.

Although there are no longer any witnesses, the desire appears to fill out the Gospel, to decorate it, especially in the literature of the simple folk. That is how the tales of Jesus’s childhood and of the Virgin Mary’s childhood and her parents came about. From century to century these tales became more and more detailed, more elaborate.

Of course there is a core of truth in such tales, however it is not historical truth but symbolic truth, and we have to talk first of all about these legends in the moral and dogmatic sense. To speak about the historical realities are behind them is, I think, not always sensible. These are texts about something else; they are given to us for another reason.

—We know that the parents of the Most Holy Theotokos, Righteous Joachim and Anna, did not have any offspring for a long time. What relationship did people in ancient Israel have to families that had no children?

—Not only in ancient Israel but in the ancient Middle East in general, children were considered as God’s blessing. Childlessness was considered a great woe. Incidentally, in that very epoch we are talking about, right alongside with the ideals of family life in Israel was appearing a definite proto-monastic ideal. The members of the Qumran community partially practiced temperance and celibacy. That is, just on the threshold of the New Testament the relationship of the ancient Jews to marriage and children as a norm and the absence of children as a disaster (at least in some circles) was changing. The words of Jesus and Apostle Paul on celibacy were no longer completely unexpected to their listeners.

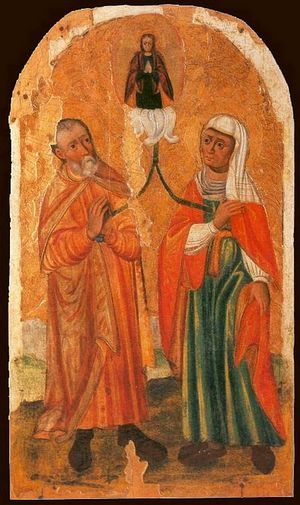

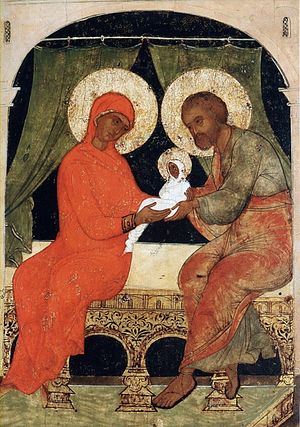

Righteous Joachim and Anna, with the child Theotokos. The ancient literary monument that relates the story of the parents of the Most Holy Theotokos, Sts. Joachim and Anna—the “Protoevangelos of James”, was written no earlier than the first half of the second century A.D. As researchers note, much of this is taken from Old Testament texts. The theme of barrenness in elderly couples, which is a sign for them of the absence of God’s mercy and a great woe, of their prayer to God, about how in old age a miracle happens and they have a child, is embodied in a whole series of Old Testament stories (Abraham and Sara, Isaac and Rebecca).

Righteous Joachim and Anna, with the child Theotokos. The ancient literary monument that relates the story of the parents of the Most Holy Theotokos, Sts. Joachim and Anna—the “Protoevangelos of James”, was written no earlier than the first half of the second century A.D. As researchers note, much of this is taken from Old Testament texts. The theme of barrenness in elderly couples, which is a sign for them of the absence of God’s mercy and a great woe, of their prayer to God, about how in old age a miracle happens and they have a child, is embodied in a whole series of Old Testament stories (Abraham and Sara, Isaac and Rebecca).

Especially close are the lines of the “Protoevangelos of James” to the story of Elkanah and Hannah (the parents of the prophet Samuel), which is found in the first chapter of 1 Kings (Seputagint). Thus did themes that played an important role for the Old Testament become relevant in the New Testament.

—We know that righteous Anna gave birth in old age. Can we call this an undoubted miracle of God?

—Tradition definitely recognizes this as a miracle, only in this case there is a hearkening back to the Old Testament; in this case the story of the conception of the Most Holy Theotokos obtains its moral sense—it becomes a lesson of patience and hope. It is once again shown to us that it is not a question of a concrete historical fact but of its symbolic meaning. If there is no miracle then there is no symbolic meaning either.

—For what does the Orthodox Church honor Righteous Anna for specifically?

—The Church honors all the forefathers (and naturally, their wives also) who have a relationship to the Savior’s ancestry. But the story of the parents of the Most Holy Virgin, as I have already said, bears an important meaning in and of itself. As in the case of the analogous Old Testament stories, there is the testing of faith. There is the testing of the family (and in part of Righteous Anna), which is experiencing grief because of its childlessness. However at the same time, faith, patience, and hope continue to live in the future parents of the Most Holy Mother of God. And a miracle happens. This very combination of themes—grief, hope, patience, prayer, and a miracle—bring us a specific moral lesson: “Those who have faith will not be put to shame”.