The current conflict between the Russian and Constantinopolitan Orthodox Churches has agitated everyone. Both believers and unbelievers, those leading an active Church life and those “with God in their souls,” have all become “specialists” in canon law and Church history overnight. It’s discouraging. It’s discouraging that the word “specialist” is placed in quotes here.

It’s discouraging that everyone started yelling in a chorus and blaming one another. It can’t but discourage any Christian who desires unity and peace for the universal Church.

Who’s right, who’s wrong? I have absolutely no desire to wander through the canonical labyrinths in search of the truth. A canon is spiritual, but it’s still a canon. And we well know what Russian folklore says about laws.1

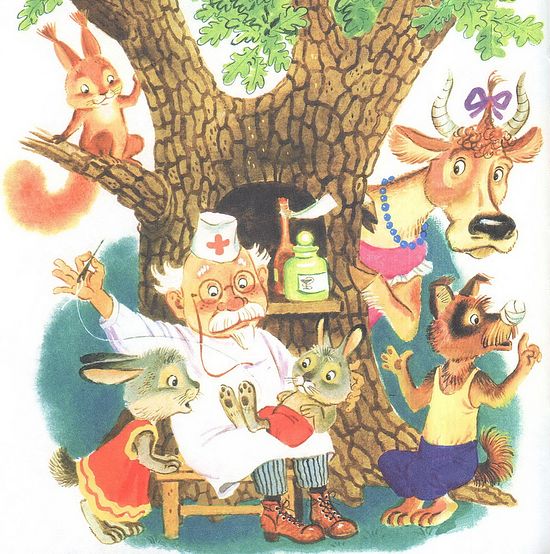

I just want to understand why some media outlets are comparing Patriarch Bartholomew of the Church of Constantinople with the good Dr. Aibolit who went to treat the Ukrainian hippos,2 and Patriarch Kirill and the entire Russian Orthodox Church with an evil doctor who interferes with the good.

To understand that Patriarch Bartholomew is by no means a good doctor, that he pursues completely specific materialistic goals, we must forget for a while about the current conflict and recall another. We must remember the Greek Orthodox Church.

Let’s try to at least briefly outline the problem. To do so, we’ll have to remember a little history. When Byzantium fell under the Turkish onslaught, the Patriarch of Constantinople became the head of all Orthodox Christians in the lands conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Therefore, he was able to extend his power to the other Local Churches that also came under the rule of the Turkish sultan. Thus, for example, the Bulgarian and Serbian Orthodox Churches lost their autocephaly.

In the nineteenth century, the Orthodox countries of southeastern Europe began to come out from under the authority of the Turks, and at the same time from the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

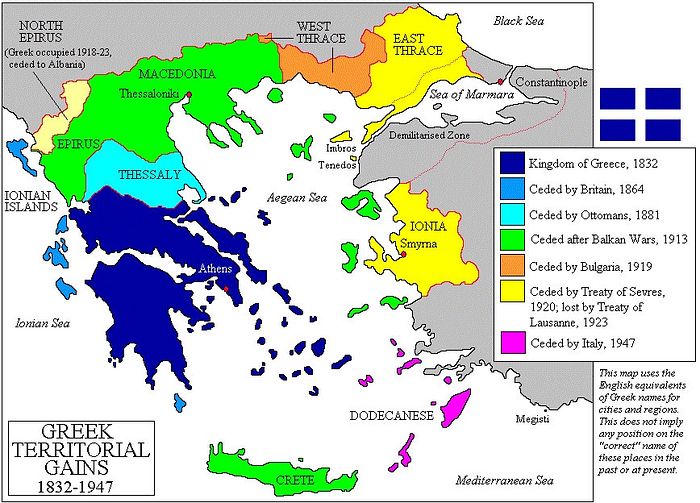

In 1821, southern Greece won its long-awaited independence. This independence was recognized by other states at the London Conference in 1830. However, at that time, only one-sixth of all Greeks (800,000 out of 6 million) lived in independent Greece and its territory was about half of its modern territory.

The Orthodox Greeks couldn’t be subject to the Patriarch of Constantinople anymore, located as he was on the territory of the hated Ottoman Empire, and in 1833, they unilaterally proclaimed their autocephaly. Constantinople recognized this act only after seventeen years. The tomos for granting autocephaly to the Greek Orthodox Church was signed in 1850. It seemed the Church situation was normalized. The Greek Orthodox Church lived and developed peacefully. Athens became the administrative center and the Archbishop of Athens the primate.

However, sixty years later, the political map of the world changed again. The Balkan Union (Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro) resolved to completely deprive the Ottoman Empire of its possessions, which it nearly completely managed to do. As a result of the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, the northern territories above the city of Larissa moved into Greece (highlighted in green in the above photo). Inasmuch as until that time these “new lands” were part of the Ottoman Empire and subordinated to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, after the change in the political situation, the question arose about their future canonical status. The Greek government and Church wanted the administration of these dioceses (more than thirty at that time!) to be carried out by the Archbishop of Athens.

For fifteen years, the Patriarchate of Constantinople did not make any decision on the status of the “new lands” until the Greek government included them in the Greek Church in 1928. Then Constantinople was forced to do something. On September 4 of the same year, the Patriarchate issued an act by which these territories were transferred to the administration of the Archbishop of Athens, formally belonging to Constantinople.

But at the same time, the Patriarchate of Constantinople put forward a number of demands, so everyone would clearly know “who’s the boss.” In particular, the document required that lists of candidates for the northern sees be approved in Constantinople.

This point caused great criticism in the Greek Church, as it made the independence of the Greeks ephemeral. Then the Archbishop of Athens sent a letter to the Patriarch of Constantinople saying the given requirement was unacceptable for the Greek Church.

A correspondence ensued, resulting in the Patriarchate of Constantinople making yet further concessions. The hierarchs of the “new lands” were chosen by the Greek Church and the lists of candidates were delivered to Constantinople only for notification, but not for approval.

That’s how it was for more than seventy years. The situation seemed to suit everyone until Bartholomew became the Patriarch of Constantinople. Then everything started up again, as the Patriarch of Constantinople, in simple terms, decided to “trample” half of the Greek Church under him again.

In 2003, Patriarch Bartholomew sent a letter to Archbishop Christodoulos of Athens in which he demanded full compliance with the Act of 1928 in the election of a new metropolitan for the vacated See of Thessaloniki and to send him a list of candidates for approval. Otherwise, the Patriarch threated to revoke the Act of 1928 and extend his full authority over the “northern lands.” Sound familiar?

The old wound flared up again. The Synod of the Greek Church discussed the problem and decided to send the list as usual—for notification, but not for approval. In their letter, they reminded the Patriarch about the history of the agreement on the practice of selecting candidates.

A new correspondence ensued.

The result was the convening of the Synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. It decided the following: The interpretation of the Act of 1928 is exclusively within the competence of the Church of Constantinople, which issued the document. Changes to such documents, such as the Act of 1928, can be made only by a similar act, but not by correspondence, even between the heads of Churches. Therefore, the Patriarchate of Constantinople insisted on the unconditional observance of the Act of 1928 and the practice of approving the lists of candidates for bishops of the sees of the “new territories.” Otherwise, Constantinople threatened sanctions.

In March of the following year, the rebelling Greek Church sent a list to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, asking for the approval of three monks of the Holy Mountain, which is under Constantinople’s jurisdiction, as candidates. Constantinople refused and noted that it would refuse from then on until the Synod of the Greek Church complied in full with the norms of the Act of 1928.

However, the Greek Church dug in its heels. On April 26, 2004, the Bishops’ Council of the Greek Church selected candidates for the empty sees, not waiting for approval from Constantinople. The candidates were consecrated over the course of the next three days after the council.

The next day after the last consecration, the Patriarchate of Constantinople gathered an extended session of its Synod. It decided to consider the election of the metropolitans invalid and to cease Eucharistic and administrative communion with the Archbishop of Athens.

Having been excommunicated, the Greek Church resisted for a short time. Eucharistic communion was interrupted for less than a month. The Synod of the Greek Church expressed its willingness to follow the Act of 1928, and this decision was called “a sacrifice for the purpose of preserving Church peace.” In response, Patriarch Bartholomew restored Eucharistic communion with Archbishop Christodoulos and approved the elected metropolitans.

In the end, Patriarch Bartholomew achieved his goal: Nearly half the Greek Church became subject to him. There was a schism in the Greek Church.

There is a dual power in the Greek Church today. Of the eighty-one dioceses in Greece, thirty are the “new lands,” which are nominally under the omophorion of the Patriarch of Constantinople. The Dioceses of Crete and Dodecanese, as well as all the monasteries of Athos are under the direct jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople and not considered part of the Church of Greece. The permanent Synod of the Church of Greece has twelve metropolitans, six of whom are metropolitans of the “new lands,” that is, conduits for the will of Patriarch Bartholomew.

The conflict has still not ended. In 2014, Patriarch Bartholomew intervened in the election of the Metropolitan of Ioannina to put his protégé Archimandrite Amphilochios (Stergiou) on the throne. The same year, a representation of the Patriarch of Constantinople to the Greek Orthodox Church was opened in Athens without the consent of the hierarchs of the Greek Church, and the same Archimandrite Amphilochios, elevated to the rank of Metropolitan of Adrianople, was appointed its head.

Soon after that, the Patriarchate of Constantinople, also without the consent of the hierarchs of the Greek Church, began negotiations with the Greek authorities about legally granting the Patriarchal representation in Athens the status of “Exarchate.”

All of this was the unspoken reason for the absence of Archbishop Ieronymos II of Athens and All Greece at the meeting of the primates of the Local Orthodox Churches in Chambésy (Switzerland) in 2016. To be continued…

So, what do we see? Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople initiated a new round of the Church schism in Greece, which Greek hierarchs often emotionally write about (“Greek Metropolitan criticized the actions of the Patriarch of Constantinople,” “Relations between Constantinople and the Greek Church continue to heat up,” etc.).

It gives us an interesting picture. “Good Doctor Aibolit,” who runs to save the Ukrainian hippos, not only forgot about his own Greeks, but also tossed them a couple of viruses. It’s hard for me to understand how it’s possible to have specific problems of your own, and, without resolving them, but only aggravating them, to go solve the same problems in a “faraway land?” Or does the Gospel used in the Patriarchate of Constantinople not have the passage about the mote and the beam (Mt. 7:3-5)?

The most interesting thing in this story is that it is “widely known in narrow circles.” Some have banally forgotten about it in the heat of debate, others deliberately do not remember because it does not fit “the format.” They don’t remember because, knowing all of this background, like Bartholomew’s interference in the affairs of the Orthodox Church in the Czech Lands and Slovakia, in Estonia, and finally, the latest curveball of the Synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople regarding the Archdiocese of Russian Orthodox Churches in Western Europe, they somehow don’t especially believe in the altruistic zeal of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

![The canonical division of the Orthodox Church in Greece[3]](https://pravoslavie.ru/sas/image/103100/310015.p.jpg?mtime=1548412262)