The Order of St. Andrew, Archons of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, held its first ever nationwide call-in Town Hall meeting on Saturday, January 26, “on the very important issue of autocephaly (independence) of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and the prerogatives and responsibilities of the Ecumenical Patriarchate,” as the site of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America wrote when announcing the meeting.

The Archons are Patriarch Bartholomew’s PR arm and fundraisers and few expected anything new from this meeting—the right of the Ecumenical Patriarchate to intervene in any Church situation anywhere, any time would be asserted again with little real engagement of the serious issues involved in every aspect of the current Church crisis in Ukraine and Constantinople’s role in it.

In large part, this expectation was unfortunately met, though the Question and Answer session had some pleasant surprises thanks to one of the panelists who dared to raise real questions, which seemed to surprise Metropolitan Emmanuel of Gaul, a hierarch of the Patriarchate of Constantinople and panelist in the town hall meeting—who seemed to have expected unanimity from the panel.

Here we will present an overview of what was said in the town hall meeting, offering clarifying and correcting comments where necessary, and highlighting the important questions raised by Dr. Vera Shevzov.1

***

The meeting was opened by the Archons’ National Commander, Dr. Anthony J. Limberakis who explained that its purpose was to to clarify facts and discuss ideas, but more importantly, to have a spiritual exchange and to share sacred wisdom. The discussion was meant to be a manifestation of the Church’s identity as ecclesia—the assembly.

He also noted that the panelists are not polemicists, that the ecclesia was not meant to be a debating hall, but that difficult question could be discussed, speaking the truth in love. He urged all to remember the goal of strengthening and defending our unity in Christ that we are called to as Orthodox Christians.

Dr. Limberakis then introduced the moderator for the evening, Dr. George Demacopoulos, an Archon, historian, and Co-Director of the Orthodox Christian Studies Center at Fordham University (a Jesuit university).

Dr. Demacopoulos began by noting that there is much confusion and criticism surrounding the recent events in Ukraine and identified three distinct issues, each easily conflated and confused with the others, that need to be addressed:

-

Questions of the reconciliation of the Orthodox in Ukraine: This time last year, Dr. George noted, there were three separate groups in Ukraine, all three theologically Orthodox, but only one recognized by the Orthodox world. Thus, what is the process for healing this division?

-

The question of the possibility of an autocephalous Church in Ukraine: The broader Orthodox world recognizes fourteen Churches—some ancient, with jurisdictions that don’t adhere to modern political realities, and newer Churches whose territories more or less coincide with modern national borders. Some Ukrainians have wanted autocephaly for a long time, Dr. George notes, so what is the process for granting autocephaly?

-

The question of the reaction of the Moscow Patriarchate: Constantinople has not reciprocated the breaking of communion, thus this is not formally a schism, according to Dr. George. Nevertheless, it is a very serious matter pointing to a series of broader questions about how Constantinople’s actions are being received by the Orthodox world.

The point about a one-way break in communion needs to be addressed. It is true, of course, but it’s not as simple as it’s often portrayed by representatives of Constantinople (though it seems to me that Dr. George was simply stating the fact of the matter and not trying to make a point). We have heard statements that the Ecumenical Patriarchate is not threatened and does not threaten, that the Ecumenical Patriarchate will not punish or break communion with Churches for refusing to recognize the Ukrainian schismatics, and that the Moscow Patriarchate’s breaking of communion constitutes an abuse of the Eucharist. The latter has been stated by His Beatitude Archbishop Anastasios of Albania, but also by Constantinople hierarchs such as Archbishop Job (Getcha) and Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware).

The clear impression that is meant to be created here is that the Moscow Patriarchate is the aggressor in this situation, that it acts too rashly, while the Patriarchate of Constantinople humbly abides it—but this is disingenuous. If your older brother is continually abusive, stealing your toys and your snacks, and so on, it is not unreasonable for you, after a year of enduring such treatment, to finally tell your brother that you won’t play with him anymore until he changes his behavior. The older brother could emphasize that he hasn’t decided to stop playing with you, but does that matter when it is his behavior that forced you into such a decision?

Likewise, Constantinople has been grasping at the Russian Church’s territory for a century, but in the present situation, it finally crossed the line, invading Kiev—the very heart of the Church of Rus’. Is the Russian Church the aggressor because it finally responded to Constantinople’s provocations?2

The accusation that the Moscow Patriarchate is abusing the Eucharist through its decision to break communion also needs to be addressed.3 This view could perhaps have merit in the mouth of the Albanian primate, but coming from Constantinople it seems, again, disingenuous when you consider that Patriarch Bartholomew himself with his Patriarchate broke communion with His Beatitude Archbishop Christodoulos of Athens in 2004 for a far smaller offense—a dispute over whether the Church of Greece should send lists of candidates for bishops of the dioceses in the “new lands” to Constantinople for approval or simply for notification.

Before that, in 1993, His Beatitude Patriarch Diodoros of Jerusalem was condemned by a council of the Greek Churches and removed from the diptychs of the Patriarchate of Constantinople for his stand against ecumenism, and for allegedly interfering in Constantinople’s jurisdiction in Australia.

The issue of the ancient heart of the Russian Church is undeniably far weightier than either of these issues.

***

Dr. George then noted that he had no control over who would ask what questions when it came to Q and A time. This was to highlight that questions wouldn’t be ruled out due to any bias, but, unfortunately, it also led to some questions that were essentially a waste of everyone’s time.

He then explained that the two panelists besides Met. Emmanuel, Dr. Dcn. Nicholas Denysenko and Dr. Vera Shevzov, were invited as experts on Orthodoxy in modern Russia or Ukraine and that they were not representing the institutional Church, or any jurisdiction, or the Order of St. Andrew—the views expressed were their own.

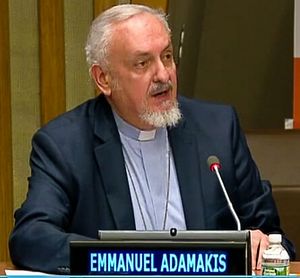

Opening remarks from Metropolitan Emmanuel of Gaul

Dr. George then introduced the panelists who then each offered their opening remarks, beginning with Met. Emmanuel of Gaul.

According to Dr. George, Met. Emmanuel “is, without any overstatement, one of the handful of people in the entire world today who is most qualified to speak on these issues,” because, “Among other things, Met. Emmanuel was appointed by His All-Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew to chair the reunification council in Kiev, serving as the Exarch of the Ecumenical Throne at that event. This council was the final step which preceded the tomos of autocephaly which was granted earlier this month. Met. Emmanuel is directly familiar with all respects of the process and we are honored to have him with us.”

Unfortunately, Met. Emmanuel did not offer any new or unique insights from his direct knowledge of all respects of the process. For those who have been following the development of this process since April, he did not offer any new information or explanations. (Dr. George’s description of Met. Emmanuel as one of a handful out of the whole world, of course begs the question: Who are the other people in the handful? Does this qualified handful according to Dr. George include Ukrainians from the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church?)

For instance, what happened at the “unification council?” Constantinople wanted former Metropolitan Simeon Shostatsky to win the primacy, as he came from the canonical Church and had a canonical episcopal consecration, but this did not happen—and there are reports of blackmail and political maneuvering to ensure that the KP’s man would win. How exactly did it come about that “Metropolitan” Epiphany Dumenko was elected as the primate and what is Constantinople’s honest reaction to this turn of events? Or he could have spoken about the Synodal deliberations that led to the decision to reinstate Philaret Denisenko, the schismatic former head of the “Kiev Patriarchate” (KP), or the Synodal deliberations that led to the decision to cancel the 1686 document that transferred the Kiev Metropolia to the Russian Church. These are serious issues that need to be illumined. There are many other such questions that could have been asked of Met. Emmanuel.

Met. Emmanuel began his remarks by noting that the Holy Synod of Constantinople decided in April to look into the issue of granting autocephaly to the “Orthodox people of Ukraine.”

Here there is the question of what it means to give autocephaly to a people rather than a Church? What analogous examples can we find in Church history? Of course, it couldn’t be said in this situation that a tomos was being given to the Church, as the Ukrainian people are greatly divided. Thus the plan was to gather all the people into a new church, though as is quite clear, this plan was not successful.

Further, as Met. Emmanuel recalls, a delegation from Constantinople went around to all the autocephalous Churches to bring to their attention the decision to create an autocephalous church in Ukraine. Note that he first spoke of looking into the issue, and now he acknowledges that the decision had already been made. The matter was also discussed at the Synaxis on September 1, and, the Constantinople hierarch says, “Everything was done openly and clearly.”

However, this is simply not true. It was announced in April that Constantinople had received an appeal for autocephaly from Poroshenko, the Verkhovna Rada, and the schismatic Ukrainian hierarchs, but there was no announcement at that time that the decision had already been made to grant autocephaly. Accordingly, it was later announced that a delegation would visit the other Churches to discuss the matter. Nothing was said at the time of “informing” the other Churches of the decision already made. The bishops in the other Churches were flabbergasted to hear the news, as I was later told. It was only months later that Constantinople representatives would speak of having made the decision already in April.

Met. Emmanuel then notes that the division into three groups in Ukraine has existed for many years, and that we all know how and why Constantinople came to find a solution and heal the wounds of the schism. However, as we see thus far, Constantinople’s intervention in Ukraine has not healed the schism in Ukraine but has only reconfigured it. The division remains and is only becoming deeper and more embittered, as many hierarchs from around the Orthodox world have noted.

Given that the canonical Ukrainian Church’s stance against Constantinople’s interference has been clear along, it is curious that Constantinople continued to carry out its plan under the banner of healing the schism.

Further, Met. Emmanuel says that the Ecumenical Patriarchate is the Mother Church for Ukraine and thus was really interested in finding a solution and that politics or geopolitics did not play a role—it was about doing something for a divided people.

It must be noted that there are different meanings of the term “Mother Church.” Constantinople was the Church that baptized ancient Rus’, and thus is the historical Mother, but “Mother Church” is more commonly used by the other Churches to refer to the Local Church to which a body belongs—thus the Russian Orthodox Church would be the Mother Church of the autonomous Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Past Patriarchs of Constantinople themselves have acknowledged and abided by this use of the term “Mother Church.” When the Georgian Church turned to Constantinople for autocephaly in the early twentieth century, it was told to turn to its Mother Church in Russia. Later, in the 1960s, when the American Metropolia (later the Orthodox Church in America), turned to Constantinople, it also was told to turn to its Mother Church in Russia (though the EP got upset when they did just that). This usage of the term can also be found in the text “Autocephaly and the Way in Which it is to be Proclaimed,” from the Inter-Orthodox Preparatory Commission that met in Chambesy, Switzerland, on November 7-13, 1993.

It is also curious that Met. Emmanuel claims that politics played no role, when only a few seconds later he acknowledges that Constantinople was actually responding to an appeal from the Ukrainian government—President Poroshenko and the Verkhovna Rada. Metropolitan Makary, the former head of the schismatic “Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church” (UAOC) has acknowledged that the initiative to appeal to Constantinople began precisely with Poroshenko, not with the bishops. Poroshenko has made no secret of the fact that autocephaly is a part of his political plan. Further, Met. Makary has acknowledged that the “unification council” in December was able to come together thanks to the intervention of several foreign ambassadors.

Several hierarchs from around the Orthodox world have also lamented precisely the political nature of the autocephaly project, including His Beatitude Metropolitan Rostislav of the Czech Lands and Slovakia and His Eminence Metropolitan Seraphim of Piraeus.

It is telling that even someone as supportive of the new Ukrainian structure as Giacomo Sanfilippo can recognize that there’s far too much Poroshenko involved in what should be an ecclesiastical matter.

It would have been far more helpful if Met. Emmanuel had addressed these concerns directly, rather than simply stating a stance that many call into question.

Continuing, Met. Emmanuel notes that Constantinople received appeals from Philaret Denisenko six times concerning the canonical sanctions laid upon him by the Moscow Patriarchate. Thus, the Patriarchate couldn’t remain silent or pretend they didn’t know what was going on. The impression left is that if you ask enough times, you’ll get what you want.

Here it must be noted that it is widely disputed that the Patriarchate of Constantinople has the right to hear appeals regarding canonical sanctions placed by another Local Church thereby circumventing the Mother Church that had placed the sanctions. Moreover, Met. Seraphim of Piraeus makes an important point—that only a Local Synod or Ecumenical Council can undo the Moscow Patriarchate’s decision, “especially given that” Pat. Bartholomew had already made his decision on the matter when he acknowledged and accepted both the Russian Church’s “exclusive competence” to deal with Philaret Denisenko and the specific sanction imposed, which occurred both in 1992 when Philaret was defrocked and in 1997 when he was anathematized.

The timing here is important as well. Denisenko’s initial appeal came before Pat. Bartholomew’s 1992 letter to His Holiness Patriarch Alexei II of Moscow and All Russia. Philaret’s appeal to Constantinople and the other primates was published in the June 1992 issue of the “Kiev Patriarchate’s” Orthodox Herald, while Pat. Bartholomew’s first letter to Pat. Alexei came in August 1992, and thus it represents a rejection of Philaret’s appeal. Thus, Constantinople’s judgment was rendered at that time.

Further, in Pat. Bartholomew’s 1997 response letter to the anathematization of Philaret Denisenko, he writes: “We informed the hierarchy of our Ecumenical Throne of it and implored them to henceforth have no ecclesial communion with the persons mentioned”—but again, the impression is that this can all be undone if the offending party just appeals enough times—even without any trace of repentance.

Met. Emmanuel continues by recalling that Philaret and Makary were received into the Patriarchate of Constantinople on October 11, being considered bishops of Constantinople in Ukraine. Then their two groups, represented by clergy and laity, came together at the “unification council” on December 15 in Kiev to elect their primate, representing, in Met. Emmanuel’s words “the voice of all the people.”

It goes without saying that this is another blatant falsehood, given that only two of the ninety bishops of the much larger canonical Ukrainian Church attended the “council,” and as we have seen in the aftermath, the vast majority of the canonical Church’s clergy and faithful have remained its clergy and faithful. The Patriarchate of Constantinople had even received multiple petitions with hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian signatures against its interference in Ukraine.

Met. Emmauel would have done better to have addressed the cognitive dissonance between Constantinople’s claim of representing all the people and the obvious reality on the ground.

The hierarch of Gaul finishes his opening remarks noting that Epiphany Dumenko’s enthronement will be on February 3 in Kiev and that they hope more bishops and faithful from the canonical Church will move into the new structure following that event and that the new structure will be recognized by other autocephalous Churches.

The enthronement has taken place since then, and no Church other than Constantinople sent any representatives.

Opening remarks from Dr. Dcn. Nicholas Denysenko4:

Dcn. Nicholas begins by immediately pinpointing four important issues:

-

The origins of the autocephaly movement in Ukraine

-

Defining the issue as a dispute between Moscow and Constantinople

-

The timing of the autocephaly

-

The crisis of representation in the court of the Church

Dcn. Nicholas notes that the autocephaly movement did not being in 1992 when Philaret left the Moscow Patriarchate but rather in 1917-1921, with its supporters seeking the Ukrainization of Church life, including the use of vernacular Ukrainian in the services and the restoration of ancient customs. As he notes, liturgical Ukrainian was originally more urgent than autocephaly, but the push for autocephaly became relentless when the Moscow and Kiev Council of 1917-1918 authorized the use of only Church Slavonic for the services.

Ukrainian identity, and especially the language, was, as he says, the primary feature of the autocephaly movement from the beginning, and indeed, for many of us reading this history and following the current news, it is hard to see anything other than Ukrainian identity here—the preoccupation with just not being Russian. It is hard to find Christ in the whole matter. (It also disregards the fact that if the opinion of all Ukrainians Orthodox were to be taken into consideration, those insistent upon the use of Ukrainian vernacular vs. Church Slavonic would, again, find themselves in the minority.)

The deacon then notes that the disputes were deeply polemical from the beginning and worsened during the German occupation in WW2. Thus, the enmity between the sides is not new but is something passed down. Therefore, he says, the only way to lasting peace is to overcome the scar tissue of mistrust and resentment embedded in the mentalities of the people of the two Churches.

Unfortunately, there is as yet no evidence that Constantinople’s actions have contributed or will contribute to this healing in any way, but quite the contrary.

Following on his first point, Dcn. Nicholas says it is therefore erroneous to view this as a crisis of Moscow vs. Constantinople, because it is primarily a dispute among Ukrainians. Dcn. Nicholas is, in one sense, entirely correct. It is the Ukrainian people who are suffering here, and they should remain in the foreground. Does a healthy Ukrainian Orthodox life require freedom from Moscow and the “Ukrainization of Church life?” Ukrainians themselves are divided here.

Unfortunately, it must be acknowledged that the Ecumenical Patriarchate has worked hard to frame this as an issue of the Russian Church not respecting, or even grasping at, the rights and privileges of the First Among Equals. Pat. Bartholomew himself has explicitly framed the issue as one of the Slavic Orthodox not respecting the Greek people’s special role in Orthodoxy. His supporters, whether official or unofficial, believe that Third Rome is an actual belief pushing the ecclesiology of the modern Moscow Patriarchate to desperately seek for primacy in the Orthodox world.

He has even said: ““We pray that the sister Churches which unjustly oppose the decisions and initiatives of the first throne of the Constantinople Church would finally begin to think logically and fairly, with great respect and gratitude to the Church of our Ecumenical Patriarchate.”

Thankfully, even Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware), a hierarch of Constantinople, recently acknowledged that Moscow does not question Constantinople’s primacy of honor, but rather, the dispute is about what that primacy means. However, in that sense, this is an issue much bigger than Ukraine, but one of ecclesiology that affects the entire Church. But all the evidence we have so far shows us that this is not a Russia vs. Constantinople issue, but an issue of the conciliarity promoted by the other Local Churches vs. the unilateralism being pushed by Constantinople. Pat. Bartholomew has yet to find a single supporting Church in this whole endeavor.

Moving on to his third point, Dcn. Nicohlas notes that the autocephalies of 1921 and 1942 did not take hold because of Soviet persecution. Then, when the UAOC attained legal status in 1989, it grew rapidly and steadily and especially in the KP, which originated within it. The canonical Church also grew steadily. The 2014 Maidan then led to even more rapid growth for the KP, becoming the point of no return for supporters of autocephaly, and it became clear that the movement is resilient. The schismatic groups had already taken autocephaly—the next step was the recognition of this after correcting the internal canonical deficiencies.

However, Dcn. Nicholas does not specify what he means by canonical deficiencies, and there has been no news of any canonical deficiencies being resolved. The schismatics were taken in as is, and have largely continued in their schismatic tendencies, especially those coming from the KP, with Philaret at the head.

The final step is then the unity of all Ukrainian Orthodox—first in the chalice and then administratively. However, it must again be said that it is hard to see how Constantinople’s intervention in Ukraine has facilitated either kind of unity.

Moving on to his final point, Dcn. Nicholas says Philaret, Makary, and their bishops have consistently claimed that they were canonical, and the rightful heirs to the ancient Kiev Metropolia. They may have claimed this (and indeed, Philaret has even stated that he did not leave the Church but the Church left him), but it is manifestly untrue. What does it mean to be canonical while in schism, without the recognition of even a single Local Church? No one recognized them as the canonical successors to the ancient Kiev Church. What canonicity is there outside the communion of the Church? Further, obviously two groups cannot both be the canonical heir to one Church.

These groups have also always claimed that the sanctions against them were politically motivated—a point which, Dcn. Nicholas says, is worthy of further discussion. I’m sorry, but it’s not worthy of further discussion. The Ukrainian schismatics and Constantinople can insist that Philaret was sanctioned simply for requesting autocephaly (and indeed, Met. Emmanuel will claim exactly this later in this meeting), but there is simply no evidence for this. The charges brought against Philaret by his own Ukrainian Church are publicly known and have nothing to do with requesting autocephaly.5 Rather, he was an abusive hierarch, he was married with children despite being a monk, and he broke an oath taken before the Cross and Gospel. He then willingly departed into schism and continued there. Makary and others were also sanctioned for departing into schism. The Body of Christ is one and will not suffer any rends. Where in this is politics? It is hard to fathom a more worthy reason for canonical sanctions.

Dcn. Nicholas concludes by noting that the vast majority of Orthodox people don’t know these Ukrainians because they’ve been so isolated and not represented in pan-Orthodox forums (a fact which, by the way reinforces that they were not canonical). He thus says that all parties in this dispute need representation.

Opening remarks from Dr. Vera Shevzov

Dr. Vera also called attention to the long history of the autocephaly movement in Ukraine and the diversity of the Ukrainian people, with modern Ukraine being made up of regions and peoples with very different histories and memories, including Orthodox memories. Western Ukraine only became Ukraine relatively recently, whereas Eastern Ukraine had been part of the Russian Empire. This history is reflected in a 2015 Pew poll that showed that 55% of Eastern Ukrainians believe Russia has an obligation to protect Orthodox Christians outside its borders, whereas 58% totally disagree in Western Ukraine.

However, Dr. Vera says this historical complexity is overshadowed by the more immediate soviet-atheist past that impacts ecclesiastical sensibilities on the ground in Ukraine today, with the people having gone through a civil war, two World Wars, famines, gulags, terror, death, etc.—this impact cannot be minimized.

Dr. Vera notes that it is painful for her to hear people say they understand the Ukrainians had a hard time, but they should get over it. This recent past must be prominent and on everybody’s mind all the time when considering the Ukrainian issue. If you don’t understand this, she says, then go and immerse yourself in the horrors of that time period.

While I cannot disagree with Dr. Vera, I do think it is worth here remembering that it was not only Ukrainians who suffered, and not only at the hands of Russians. Russians suffered too, as did all the peoples included in the USSR. Stalin was a Georgian, Khrushchev was a Ukrainian. Ukrainians were soviets as well, and the Holodomor did not affect only Ukrainians. What are the implications of all of this?

Further, Dr. Vera speaks of the soviet agenda to create a new, godless type of person—a policy that affected every aspect of life and that was further aggravated by especially Stalin’s policy of separating national and ethnic identities from religious identities. While national and ethnic identities were supported, they were drained of association with religion and were filled with new content. Textbooks call this secularization, but really it was cultural destruction.

She then quoted a passage by Nobel Prize Winner Svetlana Alexievich from Second-hand Time, as a good illustration of the background to keep in mind here:

Communism had an insane plan: to remake the ‘old breed of man’, ancient Adam. And it really worked … Perhaps it was communism’s only achievement. Seventy-plus years in the Marxist-Leninist laboratory gave rise to a new man: Homo sovieticus. Some see him as a tragic figure, others call him a sovok. I feel like I know this person; we’re very familiar, we’ve lived side by side for a long time. I am this person. And so are my acquaintances, my closest friends, my parents. For a number of years, I travelled throughout the former Soviet Union – Homo sovieticus isn’t just Russian, he’s Belorussian, Turkmen, Ukrainian, Kazakh. Although we now all live in separate countries and speak different languages, you couldn’t mistake us for anyone else. We’re easy to spot! People who have come out of socialism are both like and unlike the rest of humanity – we have our own lexicon, our own conceptions of good and evil, our heroes and martyrs. We have a special relationship with death. How much can we value human life when we know that not long ago people had died by the millions?

This immediate history, Dr. Vera said, is more important than a 300-year-old document about jurisdiction which, in any case, presumably has a canonical statute of limitations for being disputed. The point about the statute of limitations is important and will be broached again later.

The direct relevance of this is a topic of real-life faith for real-life believers and therefore the future of Orthodoxy in the post-soviet areas and for Orthodoxy as a whole, she says. The danger is that with politics surrounding Church matters, such as we see in this Ukrainian case, believers are seeing the caricatures of soviet anti-religious propaganda coming true. They remember the posters as if it’s all being reenacted again and people become disillusioned and cynical and turn away rom the Church—“the genuine tragedy of the matter.”

She then refers to a recent op ed article that rhetorically wonders who cares about Christ when there is a war on canons, churches, and holy sites to carry out? Each believer must decide for himself who to listen to.

She says another factor that isn’t being considered is that the role that narratives from Orthodox in the diaspora play in Church matters in Ukraine. Following the fall of communism, these people lacking all meaning in their lives looked to their countrymen abroad who had preserved their faith, but diasporic narratives and histories are highly selective to preserve identity in a land where they are the minority. We should look to see what role our narratives have played from our diasporic communities.

The historical memory that forms the worldview of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Greek diaspora is very different from that of Ukrainians, which is different from that of Serbians, which is different from that of Russians, and so on. We don’t know one another’s stories, Dr. Vera says, or how we are depicted in one another’s stories. This strikes me as a particularly insightful point, though, unfortunately, it was not developed at all throughout the rest of the town hall. Of course, there simply wasn’t time to discuss everything that needs to be discussed.

Dr. Vera ends her opening remarks by noting that Ukraine has become a firing range, a proving ground for various personal vendettas for Orthodox personalities, international interest groups, and so on.

Question #1: Lifting canonically-imposed sanctions

Dr. George then opened up the discussion for panelists to ask questions of one another based on what was said in the opening remarks, and Dr. Shevzov asked the obvious and pivotal question of how someone whose canonical sanctions are recognized by the entire Church can suddenly have that reversed and be accepted back into the Church. What is the basis for such a reversal?

Met. Emmanuel offered a very disappointing, though expected, response, the content of which we discussed above. He says, yes, Philaret was anathematized, but was this a just judgment? “I do not think so.”

Recall that, as we detailed above, Pat. Bartholomew himself accepted both the defrocking and anathematization of Philaret Denisenko, even after receiving Philaret’s appeal, raising no questions about the justness of the Moscow Patriarchate’s judgment. Is the Ecumenical Patriarchate therefore confessing that Pat. Bartholomew’s own judgment failed him in 1992 and 1997?

Met. Emmanuel then repeats that Philaret sent six appeals—again, does persistence really change the nature of the case? Why was five times not enough but six was?

The hierarch then says, “You all know” that it is only the EP that has the canonical privilege to receive appeals. Again, no, not all know this, and it would have been useful to demonstrate this to be true rather than to simply assert it, especially considering that Met. Emmanuel undoubtedly knows that debate about it does in fact exist.

Met. Emmanuel then says that Constantinople saw that Philaret was not anathematized for any dogmatic reason, but only because he wanted autocephaly and to break from the Moscow Patriarchate. But schism is an ecclesiological matter, and ecclesiology is dogmatic. Philaret and those like him believed it was acceptable to be outside of the Church for thirty years and to lead their flocks through this desert. It is more than concerning that a hierarch of the Church would refer to leading millions of souls out of the Church as the “only reason.” What more is needed?

Constantinople shouldn’t be criticized for receiving Philaret, Met. Emmanuel asserts—they were trying to heal the schism and to heal wounds by accepting Philaret. It is truly hard to believe that Constantinople truly thought that putting Philaret front and center (his acceptance into the Patriarchate of Constantinople, along with Makary Maletich, was a specific point in the Holy Synod’s announcement of October 11) and receiving him back into the Church would heal any wounds.

However, Met. Emmanuel says, Constantinople did not thereby recognize the patriarchate of the Ukrainian church or the patriarchal status of Philaret—he was accepted as the former primate of Kiev. The EP also did not decide to give autocephaly to Philaret or any other group. Further, Constantinople should not be criticized for granting autocephaly to schismatics, since they ceased being schismatics as of October 11, when they were received into Constantinople’s jurisdiction.

This could not heal any wounds because Philaret was received back without even the slightest hint of repentance. He never acknowledged the error of leading millions of souls into the wilderness of schism, and he never acknowledged the error of letting a distorted form of Ukrainian nationalism (that is stridently anti-Russian) dictate his religious decisions.

His behavior since October and especially since the “unification council” in December proves beyond a shadow of doubt that Philaret has not repented—he still acts a schismatic. Despite being received as a former metropolitan, he has repeatedly insisted that he will always remain a patriarch. He was instructed by Constantinople not to wear his white patriarchal koukoulion to the “council,” and he didn’t, but he donned it again the very next day and has been wearing it ever since. He has openly declared that he will continue to rule the church, “together with” his protégé “Metropolitan” Epiphany Dumenko.

More recently it became clear that when parishes leave the canonical Church and are re-registered, they are, in fact, re-registered to Philaret’s “Kiev Patriarchate,” which has not ceased to legally exist despite Philaret signing an order to dissolve the structure on the morning of the “council.” He has even boldly declared that no new structure was created, but, in fact, the tomos was given precisely to the “Kiev Patriarchate.” This point will come up again later.

Constantinople may not have intended to give the tomos to the KP or to have a Patriarch in its Ukrainian church, but that is the reality on the ground, and it is a surprise to no one who has been paying attention.

Moreover, the Serbian and Polish Churches both explicitly continue to recognize them as schismatics, and the recent statement from the OCA says that the “unification council” created a new church out of two schismatic groups, meaning it does not acknowledge that Constantinople’s decision of October 11 normalized their situation.

Dcn. Nicholas then offered a response, saying we shouldn’t look so much at Philaret’s history, because if we look just at him, it causes problems based on the common knowledge of his personal history. This acknowledgement that Philaret is a problematic figure because of his personal life seems to at least implicitly acknowledge that the canonical sanctions against him are not based in his desire for autocephaly (or at least it logically leads to this conclusion), though Dcn. Nicholas does not state this.

We need to look, according to Dcn. Nicholas, more broadly at the dispute between autocephalists and the Moscow Patriarchate directly or with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate, and then we will see power moves on both sides, and a pattern that develops of one action taken, then a response to that action, which escalates into anathemas in Philaret’s case. This does not mean, however, that these sanctions are always wrong and need to be overturned, he says.

The problem, in Dcn. Nicholas’ view, is the absence of a neutral power that can assess the matter in the court of the Church and really adjudicate the matter. Perhaps a pan-Orthodox council could take up this role? But Constantinople is stridently unwilling to call such a council. Or we can look to Canon 5 of the First Ecumenical Council that stipulates that a sanctioned cleric cannot be readmitted by a different bishop than the one that imposed the sanction. Further, if there is concern about the bishop’s motivations, then the local Synod of bishops can take the matter up. The canons do not see a need to bring in one bishop who claims to be able to intervene anywhere, anytime.

Question #2: Solving the issue by pan-Orthodox council?

Dr. George then moved on to the next question: How to respond to those who say the whole issue here is the sort of thing that can only be solved by a pan-Orthodox council?

Referring to “those who say” this gives the impression that it’s a few, or it’s a scattered opinion, but, in fact, this is the view expressed by every Synod or primate that has spoken on the matter, without exception. Even those who are very close to the EP, such as Abp. Anastasios of Albania, and even the Constantinople hierarch Met. Kallistos (Ware) have said that this issue requires a pan-Orthodox resolution.

Dr. George continues by saying it seems disingenuous for Moscow hierarchs to call for a pan-Orthodox council considering that they “refused” to attend the Crete council. This is an argument made by EP representatives and by supporters on social media continuously, but is there any substance to it?

First, we have to look at why Moscow did not go to the council. Those on the EP side of things will insist that Moscow wanted to sabotage the council because it longs for the position of primacy; though, again, there is no evidence for this. The MP was deeply involved in the planning of the council, right up to the last minute. The Russian Church only backed out after the Antiochian, Bulgarian, and Georgian Churches had backed out—each for their own reasons (though Pat. Bartholomew does not accept their stated reasons, instead openly believing that they backed out under Russian influence)—and it was already clear that the synodal focus of the council was already lost.

Moreover, we must remember that the MP had specifically proposed that the EP call an emergency pre-council meeting to address the concerns of the three Churches, and it was the EP that declined to do this, choosing instead to go on with the council without the three Churches. Then the Russian Church backed out. In light of the chronological facts, it was the Russian Church’s position that promoted synodality rather than that of the EP.

Further, is the EP and its supporters really making the argument that because the Russian Church did not go to one council it therefore can never see the need for a council ever again? Is the same true of the Georgian and Antiochian Churches, which have also called for a council here, and of the Bulgarian Church? Did the absence of four Churches at Crete really kill any future possibility for a council? That is effectively what is being argued here.

Dr. George continues: Although he thinks the MP seems disingenuous, if Crete was meant to be a recommitment to synodality, shouldn’t future councils be a welcome occurrence, that could address issues precisely like the Ukrainian situation we are presently facing?

Thus, he asks, what is the role of a future synod with respect to the continuation of the integration of the Church in Ukraine?

Unfortunately, Met. Emmanuel offers a very strange answer, saying that when the EP sent a delegation around to all the other Churches, “consulting and informing,” this was part of the synodal process. However, recall that he has already said that the delegations were sent to inform. They may have heard the Churches out, but there is no indication that there was any consultation, and how can there be any consultation when a decision has already been made? Pat. Bartholomew has been told many times by hierarchs from many Churches, often to his face, that his plans to create an autocephalous church in Ukraine would be disastrous; but what evidence is there that these warnings were ever taken into consideration or that they affected Constantinople’s course at all? There is none.

Met. Emmanuel also says that it was not the EP that closed the door to discussion, but how could this possibly be substantiated? Pat. Kirill traveled to Constantinople on August 31 to discuss the matter with Pat. Bartholomew. During that meeting, the Russian primate proposed holding a meeting of clergy and academics to discuss the history and documentation surrounding the transferring of the Kiev Metropolia to the Russian Church in 1686. It was Pat. Bartholomew who refused, saying that would delay the autocephaly process too much.

That means discussion was not welcome because a decision had already been made. And why the rush (this question will come up again later)? Can’t synodality include, if not true consultation, then at least taking the time to substantiate your arguments? Pat. Bartholomew was not wiling to do even this.

And, as we have said, Constantinople has received numerous appeals over the course of several months to call a pan-Orthodox council to discuss this matter, but obviously it has not done so. Following the “unification council,” Pat. Bartholomew wrote to all the Orthodox primates, asking them to accept the results of the “council.” His Beatitude Patriarch John X of Antioch responded by emphasizing that a synodal resolution was needed here. On January 1, Pat. Bartholomew specifically responded to Pat. John saying he would not call a council.

Who closed the door to discussion?

Met. Emmanuel also notes that until 2001 or 2002, there was a common commission with the MP dealing with the cases of the “so-called” schismatic bishops in Ukraine, he says. But it was the MP that pulled out. I do not know the history here so I cannot comment on that, but it is interesting, to say the least, that the metropolitan refers to them as being “so-called” schismatics as far as back as 2002, when even the Patriarchate of Constantinople itself considered them schismatic. What is he insinuating here?

He then notes that the topic of Ukraine came back up in the preparations for the Crete council at the Geneva synaxis of primates in January 2016, but no answer was found. So why look for a synod again, he asks, when there was no interest in coming and agreeing or disagreeing?

Again, it is not true to say that the Russian Church “refused” to go or had no interest in going. It was, in fact, very interested in going, but backed out for the reasons given above.

Should the Russian Church still have gone despite the obvious problems with the council? I think probably the Russian, Georgian, and Bulgarian Churches should have gone and raised their voices where necessary, but that does not mean they backed out to sabotage the EP or due to a lack of interest. Few will be convinced by misrepresenting the Russian Church’s positions and decisions. 6

Dealing with autocephaly as they did was the only way to move forward, Met. Emmanuel asserts. And it was done after careful study and after the appeal to the EP in April. Moreover, everyone agreed that the question of an autocephalous church in Ukraine was needed, he says, and now it’s a fact—there is a church, he asserts.

“Synodality” is not a mere word, he says. We really need to work together to not just be a federation of Churches but to show that the Orthodox Church is one Church.

This could not be more ironic or come off as more disingenuous.

Dr. Vera then offers her thoughts, based on her experience as an historian aware of the archival documents. She notes that Met. Onuphry has enormous authority and respect from his followers, and if he wasn’t ready for this autocephaly process, then it seems very rushed. Recall that Pat. Bartholomew was not willing to take the time to establish his position regarding the 1686 document.

Moreover, Makary Maletich, the head of the UAOC, spoke about how the Constantinople Exarchs were rushing them to organize the “unification council.” In the end, we know that the KP and UAOC were unable to work together and organize the “council,” so the EP took over the process.

Dr. Vera continues that Met. Onuphry has been closed out of the process and literally put on guard—the government is forcing his Church to be renamed (and since the town hall we have learned that the Church’s legal name was given to the schismatic church), his parishes are being forcefully taken and reregistered, and to the KP at that! There is great confusion on the ground, she says.

Dr. Vera is completely correct and what she said needed to be said. How could a council unify when the largest Church and the most authoritative pastor is shut out? True, the hierarchs of the UOC chose not to attend the “council,” but as Dr. Vera explained earlier, they were practically forced into that position by Constantinople’s misguided intervention.

No one could look at this process and see transparency, she says. The bishops of the other Churches are not happy about this. Something is making them pause—and what is that?

Again, this is a very important question, though several Churches have answered directly—they don’t like Constantinople’s disregard for synodality and they don’t accept unrepentant schismatic hierarchs who have no legitimate consecration.

Dn. Nicholas Denysenko then offered his thoughts, saying we need to distinguish between a council like Crete and a synaxis of primates, which are different exercises in synodality, though easily conflated.

We also need to remain committed to dialogue even when we disagree, he says, offering the example of His Beatitude Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev of All Ukraine, Met. Onuphry’s predecessor, who continued dialoguing with both the KP and the UAOC in 2008 when there was severe tension over President Yuschenko having invited Pat. Bartholomew to attend the 1,020th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus’ and to help resolve the schism. The dialogue collapsed a few years later and never started again, Dcn. Nicholas says. Met. Vladimir was invited to a synaxis of primates in Constantinople at the time of the controversy and appealed for a synodal solution at that time.

So the question we must ask and which Constantinople must answer then is—if the Ukrainian Church has been calling for a synodal solution to the schism there for at least a decade, why was it suddenly handled unilaterally?

Dcn. Nicholas continues: The appeal of Met. Vladimir and the Ukrainian government’s appeal to the Crete council is representative of all the people, in one way or another. We have already discussed how it is obvious that the appeal for autocephaly represents far from all the people.

In any case, this history shows the need for sustained dialogue, which would, of course, be a good thing, he says. What can we do to rekindle and sustain dialogue among Orthodox Christians in Ukraine who are caught up in the current mass confusion following the granting of the tomos, with churches being seized and renamed, laws touching upon Church life being passed, and so on? There is a place for pan-Orthodox participation to help resolve this issue, Dcn. Nicholas affirms, regardless of what we think about what was happened up to this point.

If even an ardent Ukrainian autocephalist can see the need for synodality, why is synodality being intentionally ignored? Recall that Pat. Bartholomew explicitly rejected Pat. John of Antioch’s call for a pan-Orthodox council.

Question #3: Ukrainian parishes abroad

Then questions from callers began. The tomos for the new Ukrainian “church” stipulates that it can have no parishes abroad, despite the fact that the KP had nearly 100 parishes in America (and there are more in other countries). Those parishes abroad are transferred to Constantinople. Many other Churches have parishes in the diaspora, so how is this limitation justified?

Met. Emmanuel responded that this issue was discussed with the bishops of the “Orthodox Church of Ukraine” and they did not negatively react. Constantinople is not trying to do anything new here, he says, but only that which is in the canons dealing with the diaspora.

On the one hand, I can agree with Constantinople here. Who can really complain about not adding yet another jurisdiction in the diaspora? However, there is much debate, of course, about the idea that the entire diaspora throughout the entire world should be under Constantinople. The famous canon referring to barbarian lands hardly refers to the entire world, despite Constantinople’s interpretation.

Further, it’s hard not to see this stipulation as a chance for Constantinople to take more parishes … which will send money to the Phanar.

And again, the KP even had parishes in other Orthodox countries, such as Greece, Moldova, and Russia—does Constantinople now have jurisdiction in their lands? And there are other canonical issues that could arise here—some of these parishes in America had broken away from canonical jurisdictions. One parish in Philadelphia recently split from the OCA just a year and a half ago. His Grace Bishop Mark of Philadelphia and Eastern Pennsylvania forbade his people from communing there, so what is the relationship now? The OCA is, of course, in communion with Constantinople, but is it that simple?

Question #4: External factors and pressure

The next caller asked for comments on the influence of external factors—Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the fighting in eastern Ukraine, and asked if the EP came under pressure from the U.S. or NATO, for example.

Met. Emmanuel responded that the annexation and war certainly play a role from the sociological point of view—without them it would have been easier for everyone to come closer. He also says that there was no pressure from outside on the EP in dealing with granting the autocephaly. I can’t say for sure of course, but suffice it to say that it has been widely believed for a long time that the EP takes directions from the U.S. State Department, and this is certainly not mere conjecture. The State Department has released several statements of support for the schismatics in Ukraine—why should the State Department care about an Orthodox issue? And recall that Makary Maletich acknowledged that several foreign ambassadors intervened in the autocephaly process. Moreover, since the granting of autocephaly, there has been pressure on the Local Churches from both governmental and non-governmental forces to recognize the Ukrainian schismatics. We have reported on such pressure on the Churches of Jerusalem, Georgia, and Greece.

The metropolitan then says that there was no pressure on the EP except for the pressure of caring about Ukraine as the Mother Church. Again, this is very hard to believe. For instance, it is well known that Pat. Bartholomew blames the Russian Church for the failure of the Crete council, as we have already discussed. The Patriarch openly said this to His Eminence Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev). Though the EP has spent the last century stealing territory from the Russian Church, it’s hard not to see the connection between such a major territory grab as Ukraine and the Patriarch’s bitterness about Crete.

Even Met. Kallistos (Ware) mentioned this as a factor in a recent interview.

Met. Emmanuel then comments “If we didn’t do it then, then when?” Constantinople didn’t act ten years ago, he says, “but we needed to act today.” He repeats that the EP didn’t act out of pressure but that it was clear that someone had to do something, and that someone is the Mother Church that gave autocephaly to the majority of Orthodox Churches—Moscow, Serbian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Georgian—so, he asks, why is it so strange to do it in Ukraine now under almost the same circumstances?

First, a few things need to be clarified. It’s debatable if Constantinople was always giving autocephaly or rather acknowledging that which already was. Orthodox Synaxis has an article to this effect regarding its recognition of the Georgian Church’s autocephaly in 1990. But the Georgian Church had declared its own autocephaly in 1917 which was later recognized by the Russian Church in 1943. The Church already administered itself independently. Further, it should be noted that the Georgian Church celebrated the 100th anniversary of the restoration of its autocephaly in 2017—that is, it counts its autocephaly from 1917—not from its granting by Moscow or by Constantinople.

And again with Georgia—the Church had actually received its autocephaly from Antioch in the fifth century. It was unjustly stripped of this autocephaly under the Russian Empire, declaring it again in 1917. But, from the ancient Church, we see that not only Constantinople can grant autocephaly. The Antiochian Church is the true Mother Church of the Georgian Church, and its ancient autocephaly is recognized in ancient canonical literature. This is a precedent that the EP seems unwilling to address or accept.

The example of the Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia is also instructive. It was granted full, unequivocal autocephaly from the Russian Church in 1951; though the EP, of course, did not recognize this. When the Church sought to normalize its relations with Constantinople in the 1990s, the EP instead granted a whole new tomos of autocephaly that severely limited the freedom that the Church had been enjoying—they became slaves, as one high-ranking clergyman of the Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia commented to OrthoChristian. Like the Georgian Church, the Czech-Slovak Church celebrated its autocephaly not from the time of the EP’s tomos, but from the actual beginning of their independent existence, when Moscow granted a tomos. They celebrated this anniversary for many years until Pat. Bartholomew threatened to rescind the Church’s autocephaly, thus forcing them to capitulate and cease acknowledging a great milestone in the Church’s history.

And as to Met. Emmanuel’s assertion that the situation now is the practically the same as with the other Churches—anyone, on whatever side of this question, can see that this is not true. When the Romanian Church was granted autocephaly, were there three competing groups, only one of which was recognized? Was the recognized Church pushed aside so that the schismatic groups could take its place? Did this happen with Bulgaria? Did this happen anywhere? No. No, the situation in Ukraine is not similar to any other autocephalies.

Met. Emmanuel then notes that the question of Kiev is also mentioned in the tomos given to Poland in 1924. Yes, the EP has used this anti-historical theory to its advantage and Russia’s disadvantage before. Even the EP hierarch Met. Kallistos (Ware) acknowledges in the aforementioned interview that the idea that Kiev has always been under Constantinople is nothing more than historical revisionism.

And, the Polish Church was dissatisfied with the rupturing of its relationship with the Russian Church and sought a tomos from Russia in the 1950s. They received a tomos that granted full and complete independence.

Dcn. Nicholas then addressed the question of external factors saying we have to be open about the strong role of President Poroshenko in advocating for, promoting, and moving forward with the tomos of autocephaly in a way that surpassed his predecessors, as well as his rule at the actual council, making sure that it concluded successfully. He also noted the post-Tomos tour around Ukraine with a copy of the tomos being taken around for veneration.

The deacon is more willing to acknowledge the political pressure from the Ukrainian side than was Met. Emmanuel, and he is right to point to Poroshenko’s large and incredibly important role in the whole affair, of which we have already spoken. Had President Putin called and presided over such a council, there would be no end to the accusations of Sergianism, KGB collaboration, and so on.

There is the possibility of the emergence of a political religion here, Dcn. Nicholas says. I think if you read any speech from Poroshenko where he talks about the tomos, you’ll see that it’s already emerged; or if you watch Philaret Denisenko’s speech at an Atlantic Council event a few months ago, you’ll hear almost nothing about the Lord Jesus Christ, but a few hours about how Ukraine needs a tomos to protect itself from the arch-villain Putin.

Dcn. Nicholas says it’s also important to understand how Poroshenko is seen on all sides: Some see him as a hero delivering on a century-old desire, while others see him as an enemy attempting to humiliate them. When you consider that Poroshenko has openly announced that those of the canonical Ukrainian Church have no business in Ukraine and should get out, it’s not hard to see why they would see him as an enemy.

He then acknowledges that it is crossing into the realm of political religion—that what happened with the Church is being exploited for purely political purposes. The only corrective here is that what happened is not merely being exploited for politics, but that what happened was always political. It was naïve to ever think it wasn’t a political project. Nevertheless, it’s refreshing that Dcn. Nicholas is able to admit this much.

Dcn. Nicholas also says there is political pressure on the other side, in particular from Vadim Novinsky, who, as the deacon says, argues vociferously against autocephaly and is involved as a political supporter of the opposition. Considering that the Opposition Bloc has not been able to stop the appeal for autocephaly in April or the anti-Church bills that have been passed, it seems hard to speak of Novinsky as a force of political pressure—more like a voice crying in the wilderness.

Dcn. Nicholas then says that all these political streams and contention go to say that this present situation will go on for a while. But this begs the question: How then was this Ukrainian minority ready for a tomos of autocephaly? The canonical Church maintains that unity should come first and then a tomos.

No matter what happens in the March elections, Dcn. Nicholas says, we have to understand that Ukraine and other countries without separation of church and state are in a different situation—it’s hard to disentangle their respective roles, with politicians either blatantly interfering or using what’s happening in the Church for their own purposes. This could be a cause for soul-searching for us, he says—can we come up with proper principles for relations between church and state, and how can we help Ukrainians to deal with this in a fair and just manner?

Dr. Vera then steps in and, again, says exactly what needs to be said, concerning the language about “Mother Church.” She notes that in a 2015 Pew poll, large percentages across the nation, both eastern and western, said that they look to their local metropolitan, whoever that may be, as the highest authority with regard to the Orthodox faith. Only seventeen percent considered the Patriarch of Moscow as their spiritual leader, and only seven percent the EP.

This helps to show that the Ukrainian Church is not just a tool of the Russian Church.

She then raises the example of Georgian autocephaly that came up in 1917. Patriarch Germanos V of Constantinople told the Georgians “I do not and cannot know a self-contained Georgian Church” since at that point it had been under the Russian Church for more than 100 years. Autocephaly must come from the Mother Church, Pat. Germanos said—that is, in this case, the Mother Church. So why is Constantinople suddenly the Mother Church here with Ukraine, she asks, when the Russian Church was the Mother Church for hundreds of years, like it or not. How is the EP suddenly the Mother Church?

Dr. Vera’s questions are exactly on point, which is made obvious by Met. Emmanuel’s answer.

The metropolitan, essentially, was not sure what to say. “I’m really surprised by the argument you are making,” he says. But, the argument she makes is the same as that made by Ecumenical Patriarch Germanos himself. Was the EP wrong a century ago?

Look into history, he says—we know who is the Mother Church of Rus’—did the Russians baptize themselves?

But did Constantinople baptize itself? With Met. Emmanuel’s logic, the Church of Jerusalem must be confessed as the Mother Church.

As we have said, the Georgian Church eventually received recognition from the Russian Church, but according to Met. Emmanuel, they were not satisfied with the recognition, because they knew that Constantinople was the Mother Church. Desiring to normalize relations with Constantinople is not the same thing as desiring autocephaly from them, though. Recall what we have said about the Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia.

“So you’re saying the EP was not the Mother Church in Ukraine. Really? I’m Astonished. I don’t know any other word,” Met. Emmanuel says. But how can he be “astonished” when this is the view held by the entire Orthodox Church, and was even the view of the Ecumenical Patriarchate itself for most of the preceding 300 years? Even Pat. Bartholomew acknowledged in Ukraine in 2008 that Kiev was under the EP until it was annexed under Peter the Great—then it transferred to the Russian Church.

If Met. Emmanuel was truly surprised and astonished that Dr. Vera asked questions that people throughout the entire Orthodox Church are asking, then he revealed how out of touch he is. If he feigned surprise to make a point, then he only missed a chance to actually address real concerns, which was what the Town Hall was supposed to be about.

It is astonishing that he could be astonished by this.

Question #5: On the KGB/FSB

Then a woman called who, after a few minutes, started talking about secret societies and how the FSB is a satanic secret society, and Dr. George rightly put an end to her question and moved onto the next one. Of course, the KGB has not existed for thirty years, and people only discredit themselves right off the bat by making accusations of KGB activity today. This is where screening of questions would have proved beneficial, though I understand why they did not do that.

Question #6: The need for autocephaly; the orthodoxy of the KP and the UAOC

The next caller responded to Met. Emmanuel’s assertion that everyone saw the need for Ukrainian autocephaly (though I think it was not clear if he was saying everyone saw the need for autocephaly or everyone saw the need to address the question), noting that the Holy Synod of the canonical Ukrainian Church led by Met. Onuphry rejected the autocephaly process and asked Pat. Bartholomew not to interfere in their territory after he sent his Exarchs. So why did Constantinople proceed with the autocephaly?

She also observed that it seems to be taken as a given that the KP and UAOC are Orthodox in faith, but were their teachings examined?

Met. Emmanuel’s answer here was, to say the least, very strange, and did not actually answer the question at all. Instead of answering why the canonical Church’s position was not respected, he blamed the canonical Church for not participating in the process that was moving ahead whether they liked it or not.

Everyone in the UOC-MP received an invitation from Pat. Bartholomew to go to the “unification council,” he says. Met. Onuphry refused to meet with the Exarchs several times, though they asked for a meeting. But, they knew ahead of time that that would be the case. He stated soon after they were appointed that he would not meet with them, and those in touch with the situation in Ukraine already knew even before their appointment that such a situation would not be acceptable to Met. Onuphry.

Constantinople held a council because of the request of the Ukrainian people—not only the president but the majority of the Parliament, Met. Emmanuel says. Do we really need to point out that the Parliament is not the same thing as the people? Time and time again, polls showed that the majority of Ukrainian were not overwhelmingly interested in the autocephaly question, so the Parliament is not representative of the people here. And recall the hundreds of thousands of signatures sent to Constantinople against their interference. And if Parliament equals the people in the EP’s mind, why do the hierarchs of the largest Church not represent the people in the EP’s mind?

So, the metropolitan asks, why should we leave millions of people living in a divided world? “Is it not the task of the Orthodox Church to deal with wounds? This is why we interfered. We did not interfere by force—we did not push anybody.”

It’s quite appropriate that he used the word “interfere.” And this interference did absolutely nothing to overcome the division of the people. The people are still divided, and moreso than ever.

Met. Emmanuel then says they know other bishops wanted to go but were forced not to go, but that there was no force from outside making anybody go to the “council.” Everbody is free, he says.

How were bishops forced not to go? How did Simeon Shostatsky and Alexander Drabinko manage to overcome this force, and why were only they able? Eighty-two of eighty-three bishops voted at the Bishops’ Council to not attend the “unification council.” Were they forced to sign? Shostatsky didn’t sign, but how was he punished? He was not punished until he himself willingly left the Church. What could the canonical Church actually do to those who would have defected? They could suspend and/or defrock them, but Constantinople just received the defector bishops and declared any sanctions from the canonical Church to be non-existent anyways. So how were they forced not to go?

But to say there was no force from outside is clearly not true. We reported on several instances where bishops were pressured and even taken to Kiev under false pretenses to try to make them attend the “council!” One bishop even had to get the terrible “vociferous” Opposition Deputy Vadim Novinsky to help him escape from the Ukrainian Security Service. Another elderly and sick bishop was stopped in the airport on the day of the “council” so the border guards could try to convince him to go to the “council.” Nevermind that he was going abroad for treatment.

Dcn. Nicholas then notes that a delegation of four bishops from the canonical Ukrainian Church traveled to Constantinople for a meeting on June 23, after which there was a detailed report and video that illustrates they had knowledge of what was going to happen. Again, this does not answer the question of why their stance was not respected, why it was ignored. Further, Dcn. Nicholas’ characterization of what happened at the meeting is simply mistaken—whether intentionally or not, I do not know.

In fact, what the Ukrainian Church reported is that Pat. Bartholomew told the delegation he did not support the legitimizing of schisms in the Ukrainian Church and did not wish to intervene in the situation.7 His Eminence Metropolitan Anthony of Boryspil and Brovary, the chancellor of the UOC, stated after the meeting:

“They spoke about the impossibility of legalizing the schism several times, but that the question of treatment should be brought up… We see that the desire of the Patriarch of Constantinople, from the Church from which we received Baptism, is to help in this matter.”

However, the metropolitan added, “His Holiness Patriarch Bartholomew said that he does not wish to intervene in the situation.”

“No one knows how the issue can be resolved, as it is very complicated, but we must do everything to ensure that our brothers and compatriots who are in a split, returned to the bosom of the Orthodox Church,” the Ukrainian hierarch added. How could he come away saying the Patriarch does not want to interfere and no one knows yet how to resolve the problem if the Patriarch had in fact informed them of his plans?

But then again, Met. Emmanuel also told members of the Russian Department for External Church Relations in May that no one was receiving any autocephaly, so the Phanar was clearly not willing yet to reveal its true plans.

Dcn. Nicholas continues stating that in the last will and testament of Met. Vladimir, the predecessor to Met. Onuphry, he wrote that he is aware of the discussions between the KP and the EP about the possibility of restoring the ancient Kiev Metropolia and the KP receiving canonical recognition—thus there is evidence in print that this process was ongoing for some years. But again, the caller’s question was not whether or not the UOC-MP knew what was going on, but why their stance was ignored.

Dcn. Nicholas did, however, answer the caller’s second question. According to him, Met. Vladimir had had a dialogue for some years between the three churches and said he was very pleased with the changes in the UAOC in particular because of their explicit condemnation of ethnophyletism on the basis of the dialogue between the UOC and the UAOC. Met. Vladimir concluded that the existing differences were not doctrinal.

That may be true of the UAOC, but the KP is quite another matter, and it would be nearly impossible to argue that they are not driven by ethnophyletistic disdain for Russia.8 Philaret and Poroshenko are hardly able to speak about anything else.

Dr. Vera then jumped in to talk about what Met. Emmanuel said about Met. Onuphry being invited to the “council” but not attending. She noted that Met. Vladimir was “very, very cautious about Philaret, to put it mildly.” So what we ended up having, she says, was a council not with Met. Vladimir’s successor but with someone else.

She also shows that she is able to understand and sympathize with Met. Onuphry’s point of view—something which Met. Emmanuel seems unable or unwilling to do. Met. Onuphry is recognized as the canonical primate in Ukraine by his patriarchal brothers around the world, many of whom came to his enthronement (or sent representatives),9 and suddenly he’s being invited to a council on his own territory? “Where are these logistics coming from?” she asks. “We need major mediation here,” she adds, because the situation doesn’t make any sense.

Anyone would take this as an offense, she says. And Dr. Vera showed she is not afraid to call a spade a spade:

“This is offensive to him. You’re inviting him to a council on his territory? With people that were not even recognized as compared to who he was? This is not serious.”

Met. Emmanuel then responds, and the dialogue between him and Dr. Vera speaks for itself:

Met. Emmanuel: I think you’re forgetting that there was in 1686—are you aware about this…?

Dr. Vera: I’m aware of 1686, I’m sorry, as an historian…

Met. Emmanuel: Are you aware of the fact that this act was revoked by the Ecumenical Patriarchate? [Dr. Vera herself had already spoken about this document earlier].

Dr. Vera: Yes, I am, and I cannot help but laugh. I’m sorry, but I cannot help but take, as an historian…

Met. Emmanuel: You have the right to laugh at whatever you want.

Dr. Vera: But there are statutes of limitations in the canons. I cannot believe that there are not statutes of limitations, that if a bishop has some kind of dispute that this can be suddenly revoked 300 years later.

As the Bulgarian Metropolitans Gabriel of Lovech, John of Varna, and Daniil of Vidin emphasize in a statement from October, the 133rd canon of the local Council of Carthage in 419 allows for three years to resolve territorial claims, while the 17th canon of the Fourth Ecumenical Council and the identical 25th canon of the Sixth Ecumenical Council allow for thirty years.

At this point, Dr. George intervened because the conversation on this point was at an impasse. While what Dr. Vera was saying was very important and Met. Emmanuel’s inability to answer was very telling, Dr. Limberakis had said at the outset that the Town Hall was not meant to be a debate, so it’s understandable that he stepped in.

Last question: Were clergy being pressured to reveal confessions?

The last question was another waste of time. The caller says he heard last year that priests and bishops were being removed by the Russian hierarchy because they would not reveal the confessions of Ukrainian laity who were fighting in the Ukrainian conflict. He wonders if the panel has heard of it, if it’s true, and if so, if it had any influence on Pat. Bartholomew’s decision.

All the panelists respond that they had heard nothing like this.

While the question was a waste of time considering the myriad of serious questions that could have been asked, it does highlight the absurdity of rumors that fly around on this issue, especially concerning the myth of the Moscow Patriarchate running everything in Ukraine and of the Church being involved in the military conflict. The Ukrainian Church has complete administrative freedom in Ukraine and any bishop or priest being removed would come through a decision of the Ukrainian hierarchy. This is clearly stated in the Church’s foundational documents.10

As that was the last question, Dr. George then wrapped up the Town Hall with some concluding remarks. In the days after the meeting, the Archons put out news that their first-ever Town Hall was a resounding success, though that would be very hard to substantiate. Only Dr. Vera really saved the sinking ship and made it worth anyone’s time; though, unfortunately, her sober and serious questions were not adequately handled.