Few people in Russia know about St. George’s Monastery on Sinai. We saw only one group of Russian pilgrims in it over two weeks of our stay there. They called at this place just for half an hour on their way to St. Catherine’s Monastery, where you can see Russian pilgrims nearly every day. Sometimes several coaches with Russians arrive there simultaneously from Jerusalem and Sharm el Sheikh. By the way, an overwhelming majority of guests in dozens of hotels of Sharm el Sheikh are Russians. And all travel agencies offer them tours to St. Catherine’s Monastery, with the only difference that some set off in the morning, while others start their journey towards the evening to climb the mount in the nighttime and view the sunrise from the mountain where Moses received the Tables of the Law from God.

One shouldn’t be surprised to see a Russian iconostasis, because Russian tsars and private individuals sent not only generous donations to Mount Sinai but also icons in settings decorated with precious stones, icon lamps, and vestments. Around 100 priceless holy objects still survive, among them is the gilded reliquary in which the Greatmartyr Catherine’s relics rest. It was sent to Sinai by Ivan Alexeevich[1], Peter Alexeevich[2] and Sophia Alexeevna[3] who considered themselves as the monastery’s benefactors. Monks of Sinai more than once asked Russian rulers to take them under their royal patronage. It was an extremely difficult task not only because of the considerable distance between Russia and Sinai and strained relations between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, but also due to the opposition of patriarchs of Jerusalem who didn’t want Russia to have an increasing influence on their canonical territory. The earliest written evidence of the contacts between the monastery and Russia dates back to the early sixteenth century. There is a surviving decree, issued by Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich in 1585, that conferred the right of Sinai monks to come to Moscow for alms. It is known that the whole of the Orthodox East sought Russia’s support and protection immediately after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The monastery archives are yet to be studied thoroughly. Should research work be properly organized, very interesting and important discoveries certainly await us.

The Biblical name of El Tor, the administrative center of South Sinai where St. George’s Monastery is situated, is Elim. It was here that Moses with the Israelites stopped at an oasis which had twelve springs and seventy palm trees. All of those springs still exist, but the palms have considerably increased in number over time. Monks settled in this area in the first centuries A.D. Many arrived here, fleeing the persecution of Decius (Roman Emperor 249—251). They lived in caves, some even in the central desert many miles away from the sea-coast. Ascetics would gather on major Church festivals and Sundays for joint prayer at the Liturgy and then disperse. Later monasteries appeared on the sites where the Liturgy had been celebrated regularly: first St. Catherine’s Monastery, and then Raithu Monastery, which later became a lavra. Tall monastery walls and churches were built by the orders of Emperor Justinian (ruled 527—565). Earlier, nomadic peoples had repeatedly sacked their sketes and killed monks. In the fourth century A.D. invaders from the Libyan Desert murdered as many as thirty-nine monks. Despite the plundering and massacres, monks never left these places, and the thirty-nine martyrs of Sinai are venerated as saints. The site of their martyrdom is famous for many signs and miracles. Every year for the twelve great feasts the Bedouin who live nearby came to greet Archimandrite Arsenios, Abbot of St. George’s Monastery on Sinai. But these people who live in the desert have no calendar! How do they know the dates of the feasts? It turns out that at every Church feast the desert sand begins to move and whirl around and the Bedouin hear something like the sound of bells from underground. Voices and faint singing can be heard from inside Jebel Nakus (“the Bell Mountain”), and the smell of incense spreads all over the desert.

Raithu Lavra was famous for the fact that at its abbot’s request, St. John of Sinai wrote The Ladder for the monks’ edification, for which he was called St. John of the Ladder, or Climacus. The full title of this timeless work is The Ladder of Divine Ascent.

The Lavra was ransacked and destroyed in the eleventh century, but the monks built a new monastery at some distance from the previous one. It was named in honor of St. George, but it was eventually ravaged too. The current buildings of the monastery are unfinished, though the construction work began in the late nineteenth century. The name of the builder and abbot of the monastery was unknown for a long time until a miraculous story occurred in 1984. At that time work on the site of Raithu Lavra was in progress. Suddenly an excavator engine stalled and wouldn't start again. When the excavator operator got out and went up to the place above which the bucket had failed, he heard a voice asking for help. He seized a shovel, trying to dig up somebody who, as he thought, had just been accidentally buried under some sand. But to his amazement he found the remains of a coffin and the completely intact body of an elderly man in a monastic habit. He informed the monastery abbot about his find. Some time later the relics of an unknown saint were enshrined in the church’s left side-altar. Remarkably, not only his body, but even his eyes remained whole.

Soon a group of pilgrims from Cairo visited the monastery. One woman refused to venerate the relics, saying that she had always been afraid of dead people. She returned to Cairo. The same night she saw an archimandrite in a dream who said to her that his name was Gregorios, that he was the builder of the church and abbot of the monastery, and that his name could be found on the facade of the church. The poor woman travelled back to the monastery early in the morning. She told the abbot about her vision, and they started looking for an inscription bearing his name together. After a thorough examination of all the walls they found nothing. Fr. Arsenios thought that these were fantasies of the woman in a state of exaltation. So he nearly forgot her until an earthquake struck the area. The plaster above the entrance door collapsed, exposing an inscription: “I, Abbot Gregorios, built this church in the year 1887.” Soon the sainthood of the man whose relics were enshrined at the monastery was confirmed by a miracle. The above-mentioned excavator operator had been childless after over ten years of marriage. He prayed all the time, entreating God to grand a child to him and his wife. When he learned that the name of the saint whose remains he had discovered was Gregorios, he began to pray to him. And a year later his wife gave birth to a healthy baby boy, though the doctors had insisted that she was barren.

On January 7, 1992, the workers who were building cells saw light in the church windows in the middle of the night and heard spiritual music. The church was locked. They looked through the windows and found that all the stasidia [wooden chairs in Greek churches.—Trans.] were occupied by boys aged ten to twelve, and an old priest in brilliant vestments was walking inside the church and censing.

Miraculous apparitions are a common occurrence in this monastery, but Archimandrite Arsenios still hesitates to make them public. The situation in Egypt has been very unstable. El Tor authorities sent an armored personnel carrier with soldiers to ensure the safety of Christians over the Paschal celebrations. The territory around the monastery that once belonged to it is now walled. Today there is a mosque with a tall minaret there. If you look from the gulf [most probably the Gulf of Aqaba.—Trans.], the monastery will be hidden, but you will see a minaret and another one a little further. During Muslim services the voice of the muezzin who shouts through a loudspeaker resounds through the area and can be heard miles away. This noise fully drowns out church services at the monastery. This mosque has the relics of St. Marina under its floor. This saint came to live at this monastery disguised as a monk (St. Marinus) and spent the rest of her life there. Myrrh streams from her holy relics abundantly, but appeals for their return to the Orthodox Church still remain unanswered.

Thus by the mercy of God I stayed at this wonderful holy place thanks to a sponsor, who gave me an opportunity to pray in this holy monastery through Holy Week, Pascha, and the patronal feast of the Greatmartyr George the Victorious so that after my return I could set to work editing his book with a pure soul. Before I arrived in El Tor my soul had had to endure many sorrows, though all had been arranged for my joy. We spent a few nights in one of the hotels of Sharm el Sheikh—an Egyptian resort town that has won the hearts of many of my fellow-countrymen. Though I had an opportunity to bathe in the warm sea and admire the coral and exotic fish, endlessly varied in color and shape, the environment didn’t make me happy at all. True, during Lent there is nothing to do in the places where everything is devoted to recreation and the entertainment industry. What annoyed me was that the service staff were even more numerous than the tourists. Several pairs of attentive hazel eyes were staring at me from under every palm tree and every corner. I was unable to take a single step without being called: “Hey, friend? How are you?” First I responded to this strange greeting, but then I began to ask them the same question in Arabic in return. The Arabs were naturally surprised with such a turnaround and talked about their state of affairs in Arabic at great length, but seeing that my knowledge of their language didn’t exceed their knowledge of Russian they stopped greeting me with the only phrase they had learned and greeted me with a nod or a movement. I concluded that the cordiality and width of the smile of these folks were in direct proportion to their expectation of tips. As a rule, most of them only knew this phrase. But some had learned Russian and made themselves understood in it fairly well. And even they pretended not to understand me when change was demanded of them or they were asked to do a service that they were too lazy to do. There were many British tourists at the hotel. They, old and young alike, were noisy and had a lot of tattoos. Aged women looked weird in particular. One of them had an ornamental design featuring sharp thorns that extended from her ankles to her neck. I couldn’t help but ask one attractive smiling young Englishman aged about twenty-five, whose entire body was covered with livid spots, depictions of horned demons, Chinese hieroglyphs and dragons: “What do your tattoos symbolize?” He answered gaily: “Nothing! These are just drawings.” He was looking at me in such a friendly way that I dared to remark, as if as a joke: “When your soul leaves your body, which is adorned so lavishly, then all the characters tattooed on it will be glad to meet it. I am afraid it won’t be particularly enthusiastic about that meeting.” The guy’s friends burst out laughing loudly, and the “adorned” fellow joined them. There was only one young woman in that company on whom I didn’t see any tattoos at first glance. Alas, it was too early for me to be glad for her because I spotted a blue spot with crimson specks above her indecent and miniscule bathing costume.

However, there was a group of athletic young black men among the British tourists. Despite the black color of their bodies, the tattoos on their skin were quite distinct. Unlike their white compatriots with satanic symbols, these guys had covered their strong bodies with “Christian” symbols. The Ten Commandments and a large cross were tattooed on one of them, a scene from the fight between the Archangel Michael and satan was on another one, and a whole chapter from Genesis—on the third one (you would need to ask him to sit still for some twenty minutes to read it!). But the latter, like his friends, jumped into the water, did a somersault, and whooped. They chased each other, running, punching the air, and nudging one another.

Glory be to God, the atmosphere in the monastery was very different. We arrived on the eve of the feast of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem. This feast is called “Pussywillow Sunday” in Russia, but since there are no pussy-willows in Egypt, they use palm branches there. To be more precise, since there are no palms in Russia, we use pussy-willows, whose furry catkins indicate the awakening of nature after its long winter sleep.

An elderly Greek was sitting in the shade to the left of the church entrance, surrounded by children (as it turned out, they were his grandchildren). They were braiding decorations of palm leaves cut into thin ribbons—stars of various shapes with crosses inside them. In the same evening their handiwork was hung all over the church, and after the Paschal celebrations they were handed out to the parishioners with colored eggs.

The father-superior gave us a cordial welcome, but throughout my stay in the monastery I sensed his anxiety. Though he knew that I was going to write an article on my pilgrimage to Sinai, he obviously was not quite sure that my main principle “do no harm” was always observed. You can expect all sorts of unpleasant surprises from journalists and writers whom you’ve never met before. We had informed him about our visit beforehand, but this didn’t help. They were expecting a huge number of guests from Cairo and Greece for Holy Week, but the guest houses were still unfinished. So there was no space to accommodate us at the monastery. We reassured Fr. Arsenios and made for the opposite side of the gulf to my sponsor’s acquaintance. He was a Russian man named Maxim; he came from Sevastopol and owned a surf club. His club was situated on the territory of a hotel complex. We rented two bungalows—small plywood sheds covered with palm stems—left our stuff and went to the monastery for the Vigil. While waiting for a taxi, we walked around the hotel grounds, namely a palm and oleander park. In it one-storied units stood in a number of rows, divided by slanting concrete partitions into separate rooms. A plaster ten-foot Osiris in a short skirt towered above a large flowerbed with his hands at his sides. He held a crooked half-crutch affair in one hand—a symbol of his power. He had something resembling a bombshell on his head, with depictions of an owl, a hoopoe, a human palm, hieroglyphs, a short wavy line, and other ancient Egyptian sacred signs on each side. Not far from Osiris, a short pyramid stood in another flowerbed, and something noisy was going on behind it. Four young Arabs with loud cries bent over their comrade, who was violently striking the ground with a stick. Then an exultant shout rang out, everybody stood erect, and the long yellow-green body of a snake rose up above their heads. The young men headed for the hotel office, laughing and talking about their success, while we hurried towards the taxi.

Before the service we had some time to admire a small park that surrounded the church. The monastery grounds are rather small. There are buildings on all sides, and there are cells that await completion to the right of the church. There is a perfectly planned space between the church and other buildings, with tall palm trees, thujas, oleanders, pine trees, and roses twining around tall arches. There is a bed of cactuses, covered with abundant yellow flowers, behind the altar. There are bushes resembling our acacia along the north fence. There are two parallel paved footpaths in the middle of the park. One runs around the church, while the other one leads to the refectory and the living quarters. There is a tall concrete circle in front of the church—a future fountain. There are two faucets by the south wall beneath a fresco depicting St. George—they are believed to be a spring.

The service didn’t begin for a long time. Everybody waited for the arrival of monks from St. Catherine’s Monastery with its abbot, Archbishop Damianos. At last the bell began to ring, and the people hurried to the church. Archimandrite Arsenios presided over the service with a few hieromonks concelebrating with him. They served in Greek, but Fr. Arsenios’s exclamations were in Arabic and Church Slavonic as well. It was a very beautiful service, and indeed Fr. Arsenios has a pleasant voice. Psaltis (cantor) Eleftherios came from Athens. He sang wonderfully, and Fr. Arsenios with other monks joined him every now and then. At this service two epitrachelia with an embroidered scene of the Annunciation and floral ornaments of striking beauty were hung by the Royal Doors. In the following days the epitrachelia were changed. At Pascha they adorned the deacon’s doors. The level of the embroiderer’s craftsmanship was astounding. Each of these epitrachelia could easily adorn not only a celebrating priest, but also any museum of Church art. It turned out that the author of these unique masterpieces was the father-superior Fr. Arsenios himself. He also made pieces of exquisite embroidery on several shrouds and palitsas [a clerical vestment.—Trans.]. Both he and the hieromonks who had come for the feast served in these palitsas.

There is no electricity in the Church of St. George the Victorious. They worship by candlelight. The Russian acolyte Andrei who often comes to this monastery lit candles on the choros with a long stick with a burning candle-end fixed to it. It is not an easy job. You need not just to light all the candles at the same time, but light according to an established rule: by groups (one at a time) in the form of a cross. He wandered around and around beneath the choros, taking several steps back to see if he had managed to light a candle; he resembled a billiard player with a cue in his hands, as if looking for the best ball to hit.

The hierarch didn’t serve at this Liturgy. The splendid carved seat under a wooden canopy remained vacant. But all the stasidia along with two rows of chairs in the center of the church were occupied. For most of the service the people listened while sitting. I appreciated an opportunity for “legalized” sitting at church because I felt quite poorly all those days and would hardly have been able to stand for three and a half hours. But after ten days of morning and evening services I was at risk of being tempted to sit down or lean against something at the first opportunity after returning to Russia.

Archbishop Damianos served next morning, the feast of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem. The meeting of the hierarch was not accompanied by ringing of the bells; he was met quietly and without ceremony, as if he were merely an elderly relative. He blessed everybody in the courtyard and slowly walked up the steep stairs with difficulty, supported by priests on both sides. He was vested in a tiny landing by the doorway. There were rows of chairs in front of him. His Eminence kissed the icons and the crucifix near the entrance, mounted the ambo, and blessed the worshippers. The priests’ choir burst forth with joy and magnificence, so all those present felt clearly that they were in the blessed Kingdom of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

Apart from several hymns, I have no knowledge of the Greek language. But this fact doesn’t prevent me from participating in their services with all my heart. You can just listen and look at the celebrating priests, while repeating Jesus Prayer or “Lord, have mercy” in your mind, and you don’t feel uncomfortable because you don’t understand their words. Without the head’s involvement, the soul feels that it is in the house of God and rejoices at this.

There are several differences between Greek and Russian services. And some peculiarities of the services of St. George’s Monastery are explained by the fact that its “community” consists only of Fr. Arsenios and Hierodeacon Dionysios, and the monastery’s church in effect has become the parish church for a handful of Orthodox families living in El Tor. These are Greeks, Egyptians, and Arabs. The Creed is only sung by child subdeacons and not by the whole congregation. First the Greek children in sticharia aged six to eleven come out, and they are followed by young Arabs of the same age.

His Eminence sat down on his bishop’s seat under the canopy and sang along with the celebrating priests and the psaltis joyfully. At certain points he was given a book and he did the prescribed readings alone. The archbishop’s eyesight is poor so he has to use a strong magnifying glass every time. Subdeacons on both sides provided him with light from lanterns. But it didn’t confuse the hierarch—he read joyously, and when he finished, he looked around at the priests and parishioners with his eyes that radiated love. And his joy spread to everybody. And nobody paid attention to his infirmity anymore. I had a chance to watch Archbishop Damianos for a few hours. During the service this joy turned into rapture now and then. And after the service, when by tradition the people proceeded from the church into a large parish hall for coffee, Archbishop Damianos’s facial expression changed. It became like that of a child. He turned his face towards those who addressed him and looked at everybody with love. He communicated with the people for over an hour, and the joyful expression didn’t leave his face for a single moment.

Fr. Arsenios introduced me to him, calling me “a church writer”. His Eminence seized my hand and spoke with fervor for a long time about how important it is to tell modern people about the Church and Christ, and about modern life of monasteries. “People think that Christianity belongs to the past, to the time when Christ lived on earth, when the Church was established, and when the first martyrs suffered and laid down their lives for their Divine Teacher. These people claim that now life is different. The world has seduced everybody into a whirlwind of fuss and vanities, entertainment, hard labor, wheeler-dealer finance, and the pursuit of lucre. So ever more people are walking away from Christ. And we need to remind them that Christ is not our past, but our present and that He is with us forever. And all the talk about progress (that pushes the Lord into the background) is empty and silly. Only what is conservative and what keeps the world and mankind from destruction is progressive. The salvation of the world is in observing the commandments of Christ and not in vulgar progress. The commandments are immutable and they won’t change till the end of time. And we must speak about this interestingly and with great talent. I bless you to write about the Church and the Truth of Christ!” His Eminence made the sign of the cross over me and didn’t let go of my hand for a long time, looking into my eyes affectionately.

Everybody was having fun. Those sitting next to each other at the table were talking cheerfully and rather noisily. All but one hieromonk, who was sitting next to Archbishop Damianos. It was clear that he was deeply immersed in prayer, and that neither the general conversation nor the noise disturbed him. He had an ascetic appearance with a thin face and a very long beard. He was sitting with his head hung low and his eyes closed. For all the contrast, he was an integral part of the gathering of monks and parishioners in the room. And it was not a mere pose, as if to say, “I am praying, while you are enjoying yourselves.” I was told that it was Hieromonk Justin—an American who had embraced Orthodoxy.

When everybody went out to the courtyard, I came up to him. Since he had heard our conversation with Archbishop Damianos, there was no need for me to introduce myself. Much to my surprise, he started talking readily, and when I asked him how he, an American, had ended up on faraway Sinai, he told me his story. He was born to a Protestant family, in which life was devoted to a strict observance of the commandments. He used to pray from his childhood, but one question kept tormenting him: “Why do people of my denomination only know of the Church in the first centuries and beginning from the reforms of Martin Luther?” After all, there was a long period of fifteen centuries between these points. So he set about studying Church history and finally discovered a wonderful world. The more closely he studied this realm, the stronger was his desire to visit the places where our Lord spent His life on earth and where the first monks performed their ascetic labors. As soon as he arrived on Sinai, ascended the holy mountain and attended a service at St. Catherine’s Monastery, he felt the real presence of God in this place. And he has never left this place ever since.

Fr. Justin and I had a short conversation. A monk approached us and said that the archbishop had asked Fr. Justin to come to him. And I started walking along the footpaths and looking at the parishioners who had broken up into groups attentively. One Greek, seeing that I was joining neither the Arabs nor his compatriots, came up and spoke to me in English: “We are so blessed to have such wonderful yet simple father-superior and archbishop! They find time and kind words for everyone.” Having nodded to my video camera, he continued: “His Eminence is a man of holy life. He is a great man of prayer, though he conceals his spiritual exploits. He is never bossy and never tries to look important. He is loving and considerate with everybody. He is a simple person and often ‘plays the fool’. As long as his eyesight allowed him, he liked to take pictures. He used to catch people during services. One day His Eminence was given the double candlestick and triple candlestick, while he was taking photos from the ambo. He took the double candlestick into his left hand, while holding the camera in his right. Thus he blessed the people with the double and his camera! Another time, he was serving in the church where the choros hung very low. When he was going around the church and censing, he accidentally caught his miter on the choros. Thus his miter was left on the choros. His Eminence, while still censing, returned, squatted, took aim at his miter, and put it back on his head without even using his hands to help! And he went on, without stopping his censing and singing. For all his simplicity, his archpastoral ministry is wonderful. And there are so many problems today.”

There was one more person in the yard who didn’t join any of the groups. He had a huge black beard and tousled hair. He was in shabby jeans and a checkered shirt that resembled a plain Soviet product. I took him for a Russian guy. It turned out that he was a Frenchman who had been wandering across the East and visiting Orthodox monasteries for the second month. Though he liked our services, he still hesitated and was unsure whether he was ready to become Orthodox.

Soon we were invited for the meal. I was seated next to Psaltis Eleftherios and his wife Mirophora. They are a marvelous couple. Quiet and meek, they speak in a low voice as if fearing to awaken somebody. Mirophora followed all services with a book. Her lips were moving silently and I understood that she was singing to herself with her husband. They both have been dreaming of visiting Russia for a long time, they know a lot about our saints and shrines. After the meal the archbishop left with the monks.

Next morning Eleftherios, Mirophora and I went to St. Catherine’s Monastery. We passed through St. Moses’s well, surrounded by palm trees. The well itself is in a round pavilion, with several pools near it, with tanned boys jumping in them with loud cries.

We couldn’t arrive before the beginning of the service because we were stopped at checkpoints about five times. Checkpoints can be found everywhere in Sinai, but on the road from El Tor they are in every corner. An officer came up to us at the first one and demanded to see our passports. But I hadn’t brought my passport with me. “What should I do?” I turned to my Greek friends and repeated the demand of the Arab soldier strictly. I gave him the couple’s documents, while praying hard to the Greatmartyrs Catherine and George to do something to prevent the officer from remembering my document. And guess what happened next? The soldier thumbed through the Greek papers, gave them back and allowed us to proceed. And the same story happened again nine times! When we told Fr. Arsenios this, he smiled: “You, dear writer, wanted to know about miracles… You should have been imprisoned ten times… And I would have pleaded for your pardon for a whole month. It is extremely difficult to talk around Arab soldiers.”

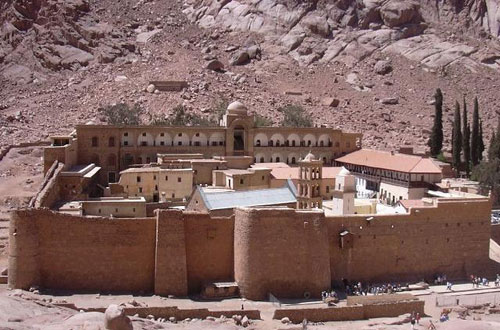

St. Catherine’s Monastery on Sinai

St. Catherine’s Monastery on Sinai

I had visited St. Catherine’s Monastery and watched the sunrise on Mount Sinai before then. But my Greek companions were travelling on Sinai for the first time. The museum was opened especially for us and I once again enjoyed viewing the fine exposition of ancient books, church vessels, and icons created before Iconoclasm. We were also shown the Burning Bush. There were two hours left before the beginning of the evening service, so we decided to examine the exterior of the monastery. Having walked along the solid monastery wall as far as the path leading to the summit of the mountain, we turned right and walked up the “Moses path” for a while. Some Bedouin boys tagged along after us. Trying to shout each other down, they offered camel services to us: “Camels, camels!” thinking that we were going to go up to the top. The camels were lying alone or in groups, hiding from the sun in the shadow of huge boulders. They were not easy to spot. Soon we wanted to cover ourselves from the scorching sun too. When the temperature is thirty-eight degrees Celsius in the shade and there is no shade, it is difficult to walk in the open. We hurried back and lingered in an olive grove right till the beginning of the service. Though we couldn’t stand through the service because we had to travel back to our monastery. We were led up to the place where God appeared to the Prophet Moses and were allowed to venerate St. Catherine’s relics. I couldn’t tear myself away from the icon of the Savior of Sinai, recalling how several years before a missionary had been speaking about Christ, placing a reproduction of this icon on the table. He spoke fast and confidently and when he had finished, a man came up to him and stood for a long time, examining the Savior’s image. Then he addressed the missionary: “I don’t believe in you very much. But if I happened to meet Him, I would believe in Him.”

On our way back the story with passport control was repeated. When we were at a fair distance from the monastery, at a checkpoint we were told to turn around and go via Sharm el Sheikh. It meant we had to make a big detour of over sixty-two miles. It took our driver a long time to get permission to proceed. He called somebody several times and put the officer on the phone each time. I was worried to death there. A fifty-strong crowd, armed with kalashnikovs, was moving to and fro between an enormous armored personnel carrier with a large-caliber machine-gun on top and a guard box. There were some boys among the elderly soldiers. The submachine guns of some of them were being dragged along the ground. I didn’t want these people to drag me out of the vehicle and leave me in their company. In my mind I was crying from the bottom of my heart, imploring St. George the Victorious to save us. And I got added evidence that he is quick to help, that he as a former warrior knows those in military service well and has power over them. They let us go past. And I had forgotten that it was only a stone’s throw from the Israeli border. Although at the hotel we were given papers warning that there would be maneuvers for a few days and that the tourists shouldn’t be afraid when they saw combat aircraft in the sky and heard explosions. Glory be to God, a war didn’t break out.

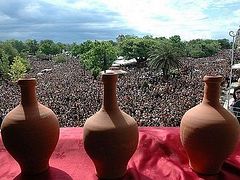

Holy Week flew by as one day. On Holy Wednesday a coach with pilgrims from Cairo came. On hearing the engine noise, Fr. Arsenios walked out of the church and, seeing the guests, he ran quickly down the porch stairs and spread out his arms (just as children imitate a plain in flight). He didn’t drop his arms for half an hour, embracing his new guests. These were his old friends and spiritual children who came there for Pascha every year—there were both Greeks and Orthodox Arabs among them. Later one of these Greeks told me that it was extremely difficult for him to stay in Cairo on great feasts, so he travelled to spend them there with Fr. Arsenios. He had a kind of “Sinai syndrome”: he couldn’t live without St. George’s Monastery. Now the church seemed very crowded, so they brought some extra chairs. People stood in the aisles and even on the porch, keeping the door open during services. Everybody was noisy and cheerful. We felt sad only on Holy and Great Friday. On other days we heard people laugh and talk loudly. But it is wrong to judge the people who have come to their beloved spiritual father. For them the anticipation of Pascha was a weeklong foretaste of a great joy. The same gentleman said: “How can we be sad knowing that the Savior triumphed over the world and death itself?” Fr. Arsenios was glad to have visitors and didn’t hide his joy. There were general talks after each meal. But even after these talks somebody “caught” the father-confessor to tell him about their problems, and the pastor expressed a heartfelt sympathy and gave them a piece of good advice. I don’t know if the father-superior managed to sleep at night, but he certainly had no chance to have a rest in the afternoon after long services. One gentleman (who would sleep during all services) did it for him. He would sit on his stasidion, with his head dropping on his arm that he would raise as if he were swimming freestyle. Nobody judged this “swimmer”, though he was pulled up every time he began snoring and nearly drowned out the service. The fact is that he worked in the nighttime, hence his day/night confusion. That week in the monastery was a period of respite that he needed and “spiritual nourishment” for him. But, when needed, he sang along with everybody else and was among the first to approach the Holy Chalice. And he kept vigil through the Paschal service. Greeks do not behave in church like Russians. Quite a lot of things are forbidden in Russian churches (and this is strictly observed by elderly women in particular), while there are no such bans in Greek churches. Greek women don’t wear headscarves at church services. They take Communion without confession. And no “keeping the doors of their lips” (cf. Ps. 141:3) after Communion—they talk cheerfully without a solemn and stern look on their faces. No Greek will say: “I have just taken Communion, so I cannot kiss you now!” On the contrary, they exchange kisses and have fun like children. I was especially amazed by the fact that having taken the antidoron, Greek parishioners shake off the crumbs by striking their palms against each other. In Russian churches some old women will lick off a crumb of antidoron from the floor after dropping it inadvertently. I didn’t see any special reverence for the bishop and the archimandrite either. Pastors and laity communicate as equals. And clergy themselves obviously don’t encourage “respect for rank”. When the priest greeted them with the words “Christos Anesti!” (“Christ Is Risen!”), they responded “Alithos Anesti!” (“In Truth He Is Risen!”) somewhat faintly and listlessly. They say that Fr. Arsenios suggests that his spiritual children go and attend the Paschal service in Russia someday and hear Russian people respond to the priest with thunderous rapture: “In Truth He Is Risen!” When once I started “reproaching” a Greek for the laxness of the Greek Orthodox, he replied that the Greek nation had come to know and love Christ 1,000 years earlier than Russians and the fact that it bothered me (in his view) indicated that the Greeks have a special “family” relationship with the Lord.

Sometimes there were intervals of five to six hours between services. Fr. Arsenios would sometimes begin the evening service at seven in the evening. I didn’t have a room in the monastery, so I would spend the periods between services in my bungalow at the sea coast. At times I bathed in the sea, from where a magnificent view of the city with tall minarets, the Coptic cathedral’s bell-tower and mountains in the background opened up. Alas, the heat haze distorted distant views of these. The monastery church was not visible due to the proximity of the mosque. Only one spot showed green: these were the crowns of palm and pine trees over the monastery wall.

Crows were cawing harshly and continually above my bungalow. I didn’t see any other birds there. Strangely enough, there were no white seagulls circling above the water and ships. Sometimes some grey, almost black, birds flew by. Soon my extremely poor knowledge of ornithology was exposed. It turned out that these were seagulls! Their black color was most probably explained by the hot sun: the birds get “sun-tanned”. Even people are black on the opposite side of the sea, some twenty-five miles away.

Sometimes I spoke with Russian surfers there. They, poor things, were suffering because of the calm weather. Their surf boards stood vacant. Our guys didn’t know what to do with themselves, so they lay down on a beach bed (some sixteen feet wide), smoking hookah and watching comedy TV shows from Kiev along with Kin Dza Dza—the favorite movie of the surf club’s owner. Sometimes they “did Ku” [“Ku” is a joking greeting, like “hi”, from the movie mentioned above.—Trans.]: bowed low jokingly, squatted and spread their arms. Though these chaps were nice, they were not interested in their “neighbor”—the great Orthodox monastery. Although on Pascha they did dye eggs and some of them came to the monastery to have them blessed. On Holy and Great Friday the strong wind rose, and our guys floated on boards and under sail around the gulf from the morning. One adroit surfer caught the air with his parachute and rose high up above the other surfers. Thus they had fun on the saddest day of Holy Week. And muezzins’ calls were unusually loud on that day too. And there was music blasting out from the joints on the seafront. Not only oriental music, but also hard rock (which I hadn’t expected in this Muslim region). The din flew far out over the water. It was as deafening at the distance of over a mile as it would have been a few yards away. It seemed as if hell were celebrating its victory—the death of the Son of God on the Cross—without suspecting His impending Resurrection.

Meanwhile, the solemn yet sad services of Holy and Great Friday were being held on the opposite side of the gulf. The Burial Service of the Holy Shroud was accompanied by such beautiful singing that many were standing with tears in their eyes. On the arrival of the pilgrims from Cairo they began to sing by turn in Greek and Arabic. Arab psaltises were no less skillful singers than their Greek counterparts. I had never heard any Orthodox services in Arabic before. They are as beautiful as Greek services. And the Arabic language is transformed in Orthodox chants. It is different from everyday language of the street. It seemed to me that it is softer and “bolder” than Greek. But it is just my personal impression, and many won’t share it. Whenever the right choir finished a verse in Greek and the left choir immediately took up the last note, while it was still in the air, and vigorously continued singing in Arabic and then Greek words were heard again, it seemed as if the powerful waves of Divine sounds were coming down on the noise of the sea of life, calming it down, transforming and taking it high up to the heavens. The singing of the Paschal service was especially beautiful and majestic. And Fr. Arsenios was even more inspired than usual, crying out “Christ Is Risen!” in three languages. The Orthodox people—local Orthodox along with those who had come from Cairo and Russia—felt the Paschal joy. And I, sinful as I am, suddenly felt homesick for Russia and remembered Afanasy Nikitin [a great Russian traveler and explorer who stayed in India between 1466 and 1472.—Trans.], who travelled to a faraway land but grieved at being unable to live as a Christian and had nowhere to take Communion amid the people who, though kind and beautiful, belonged to another faith. As for me, I was among people who took Communion through Holy Week at every Liturgy. All but four Russian pilgrims would receive Communion in the church. We partook of the Holy Body and Blood of Christ on Holy Thursday and on Pascha. Nevertheless, I missed that grace-filled joy that I have always experienced in Russia. No matter how many times they say that the heavenly fatherland shouldn’t be overshadowed by our earthly one, I most probably won’t be able to grasp this great truth. That is why I have decided not to leave Russia on the days of Orthodox feasts.