View towards Portland. Photo: VisitEngland/South West Coast Path/Steve Luck

View towards Portland. Photo: VisitEngland/South West Coast Path/Steve Luck

Dorset, which lies on the English Channel, is one of the most beautiful counties of southern England. It is mainly hilly, but low-lying in the east and has glorious countryside throughout. It is famous for around 100 miles of golden sandy beaches; the Jurassic coast with abundant fossils and other archeological finds, which became the first natural world heritage site in England; a rich agricultural heritage (notably, in spring the county is covered with stunning yellow squares of rapeseed fields); picture postcard villages; such natural wonders as Chesil Beach, Durdle Door, Golden Cap, Lulworth Cove, and Pulpit Rock. The city of Poole has the largest natural harbor in the country, and the Isle of Portland (a rocky limestone peninsula on Dorset’s southern tip) has been quarried for its fine building stone for centuries.

For hundreds of years Dorset landscapes have inspired a host of writers, artists, and scientists. Thomas Hardy (1840—1928), a renowned novelist and poet, is perhaps the best known son of Dorset. Rural Dorset is the setting to most of his novels—he called his fictional country “Wessex”, which is fair as in the Anglo-Saxon period Dorset was part of the kingdom of Wessex. In addition, Dorset holds many different festivals and is home to some of the finest local produce in the country. In “the age of saints” numerous churches, monasteries, missionary centers and hermitages were founded in Dorset, and many saints lived and served in this region. Now let us speak of one of them, who was a native of Dorset.

***

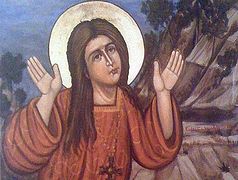

An icon of St. Wite of Dorset. It is sad that so little is known about St. Wite (Candida, Gwen, Blanche; her name means “white”), one of the most beloved and visited saints, venerated by modern Orthodox living in the UK. By irony, she is in a very select company of local early saints whose shrines and relics have remained undisturbed in their resting-places from before the Norman Conquest and that even survived the bloody Reformation1. In other words, their veneration has continued for over a millennium without interruption. And today numerous miracles still occur by the prayers of St. Wite of Dorset both near her relics and her holy well. Let us recall who she was.

An icon of St. Wite of Dorset. It is sad that so little is known about St. Wite (Candida, Gwen, Blanche; her name means “white”), one of the most beloved and visited saints, venerated by modern Orthodox living in the UK. By irony, she is in a very select company of local early saints whose shrines and relics have remained undisturbed in their resting-places from before the Norman Conquest and that even survived the bloody Reformation1. In other words, their veneration has continued for over a millennium without interruption. And today numerous miracles still occur by the prayers of St. Wite of Dorset both near her relics and her holy well. Let us recall who she was.

Unfortunately, we cannot say for certain when exactly this saint of God lived. According to a long-standing tradition, maintained for centuries in Dorset, St. Wite was a local righteous woman who lived in the ninth century in Charmouth, now a spot two miles away from the village of Whitchurch Canonicorum, where her relics have been kept. It is possible that she was an anchoress who served God in unceasing prayer and solitude, maintained fires as beacons on the cliffs to protect sailors, and was eventually martyred by the pagan Danes, who through the ninth century made regular raids on English monasteries2. Not only did these Vikings attack, plunder and burn down monasteries situated both near the sea coasts and inland, they would also lay waste to the surrounding countryside and put to death Christians and ascetics. St. Wite most probably fell victim to one such raid. Some scholars give the year 830 as the possible date of her martyrdom, though no early records of this saint survive.

However, some who speculate have put forward alternative versions about St. Wite’s origin and life. Some claim that she was not an Anglo-Saxon woman from Dorset, but the Welsh princess St. Gwen, who lived in the fifth century and became the mother of two Welsh saints. Others claim that she was the martyr St. Candida who was executed in Carthage in the fourth century; others—that her name is a corruption of the male name St. Albinus (Witta) of Buraburg, one of the companions of St. Boniface, the enlightener of Germany, whose relics were allegedly translated to England by King Athelstan in the 930s and enshrined in Dorset (it is known that Athelstan collected relics of many saints and arranged for them to be brought from the Continent to monasteries of south-western England). But it is obvious that the above versions are groundless and not based on any documents or traditions, and we think it would be much more reasonable to rely on the mainstream and local oral tradition of Dorset.

Tradition says that soon after her death St. Wite’s relics were translated to the chapel of the village of Whitchurch Canonicorum (the name means, “St. Wite’s church of the canons”—the first church on this spot was owned by the canons of Salisbury). This village sits at the south-west extremity of Dorset, between the towns of Bridport and Lyme Regis, in the valley of the River Char, in a very idyllic area, and its name in this form is first mentioned in 1262. The chapel (and, later, church) in the village was dedicated in her honor in Latin—St. Candida’s Church. In the late ninth century King Alfred the Great gave this church, which he may have founded, to his youngest son Aethelweard. Soon numerous pilgrims began to visit this shrine and many miracles were performed by the holy maiden, anchoress and martyr.

After the Norman Conquest, the church was given to the Abbey of St. Wandrille of Fontenelle in Normandy and in 1190 it was granted to the Bishop of Sarum (later called Salisbury). By the thirteenth century the parish of Whitchurch Canonicorum had become one of the largest in England, and the bishops of Salisbury demanded that its parish tithes be paid directly to them. The chronicler William of Worcester and John Gerard (the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries) both mentioned St. Wite’s relics, while Thomas More referred to the custom of offering her cakes and cheese on her feast-day, which was confined to her church—according to the Oxford Dictionary of Saints.

It is a real miracle that St. Wite’s relics were not destroyed and her shrine was not even touched during the Reformation and the Cromwellian atrocities, while nearly all the saints’ relics, shrines, icons, statues, carvings, stained glass and other images were barbarously destroyed, smashed or burned down. Perhaps her shrine looked so humble that it was mistaken for an ordinary tomb of little significance and spared.

St. Wite's shrine inside the Holy Cross and St. Candida's Church in Whitchurch Canonicorum, Dorset (photo kindly provided by the churchwarden of this church).

St. Wite's shrine inside the Holy Cross and St. Candida's Church in Whitchurch Canonicorum, Dorset (photo kindly provided by the churchwarden of this church).

Her precious relics rest to this day in the thirteenth-century stone shrine, set in the wall of the north transept of the Anglican parish church of the Holy Cross and St. Candida. Her tomb was rediscovered accidentally in 1900, when a crack appeared on this medieval structure. It was decided to repair the shrine which was believed to be empty. To the amazement of the vicar and congregation, a leaden coffin, on which was inscribed, “Hic requiescunt reliquie sancte Wite” (“Here lie the relics of St. Wite”), was found inside it and opened. The well-preserved bones of a small woman were discovered inside. Judging by her remains it was concluded that the woman lived in about the ninth century, was aged about forty, and led an ascetic life. As is the case with medieval reliquaries, the shrine still has three oval holes in its base (the actual shrine consists of two parts: the lower base with the openings, and the upper stone coffin which houses the leaden casket with the relics), where people can place their sick limbs in the hope of healing. Before the Reformation it was a popular custom to insert the hands or other parts of the body into these openings, or place handkerchiefs, bandages, notes or other personal articles belonging to the sick person on his behalf by someone else if the person in question was too weak to walk to the church, and then bring them back to him. Many believed that this helped. In addition, it was a custom in the Middle Ages to light a candle with the length equal to that of the cured body part after the healing. And nowadays this practice has been revived in some sense: hundreds of paper prayer requests, photographs, testimonies of healing and offerings of thanksgiving are left here by pilgrims from all over Britain and abroad. The faithful note a particular atmosphere of holiness and peace inside and around this church and find it a unique experience to stand at St. Wite’s shrine and pray to her just as thousands of medieval Christians did for centuries on the same site.

Parish Church of St. Candida and Holy Cross in Whitchurch Canonicorum, Dorset. Photo: Wikipedia.

Parish Church of St. Candida and Holy Cross in Whitchurch Canonicorum, Dorset. Photo: Wikipedia.

The Church of the Holy Cross and St. Candida stands in a very quiet, rural setting. Although it stands on a Saxon foundation, this unusually large church for a small settlement retains the features of the Norman (the arcade, the south aisle), the Early English and Perpendicular Gothic styles; its massive bell-tower, a local landmark, is seventy-five feet tall. The church has a chancel, a nave, two transepts, two aisles, the porch, and a vestry. The baptismal font in the shape of a chalice is Norman, and the rare carved pulpit is Jacobean. The tower walls have a number of ancient carved stone panels, one of which depicts a Viking longship and an axe—symbolizing St. Wite’s martyrdom at the hands of the marauding pirates. This magnificent church is nicknamed “the Cathedral of the Vale”—the “Vale” in this case is Marshwood Vale.

Orthodox, along with Catholics and Anglicans in England come and venerate St. Wite’s relics, and Whitchurch Canonicorum remains a popular pilgrimage destination for believers, not least Russian Orthodox.

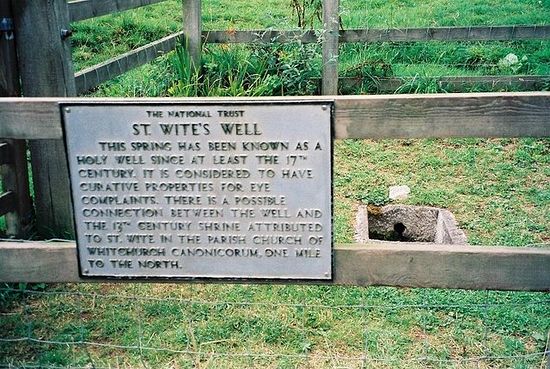

St. Wite's well in Morcombelake, Dorset. Photo: Wikipedia.

St. Wite's well in Morcombelake, Dorset. Photo: Wikipedia.

There is St. Wite’s holy well in Morcombelake in the vicinity of Whitchurch Canonicorum, which is also visited by pilgrims. This little holy well of pure water is a mile south of St. Wite’s shrine. It was first mentioned in a 1630 document claiming that the saint herself used to live and pray near this holy source. It can be found on a hillside surrounded by flower gardens. The water gathers in a small basin, and a path leads right to it. The area is enclosed to protect it from animals. St. Wite’s well is famous for healing eye diseases and other complaints. Orthodox pilgrims come to it, sprinkle themselves with its pure water, wash their faces, drink it and collect it for home use. Interestingly, wild periwinkles that bloom around it in plenty are often referred to as “St. Candida’s eyes”.

It is very important that miracles through St. Wite’s intercessions still occur nowadays, and there are many testimonies to them.

There is a modern Orthodox service to St. Wite in English.

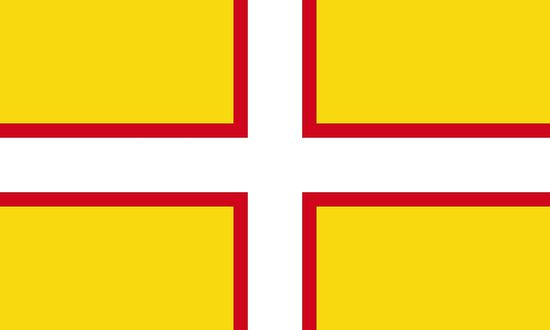

The Dorset Flag, or St. Wite's Cross.

The Dorset Flag, or St. Wite's Cross.

The flag of county Dorset, known as “St. Wite’s Cross”, is dedicated to this saint. It was adopted in 2008 and features a white and red cross against a gold background.

From the service to the Venerable Martyr Wite, Anchoress of Charmouth and Wonderworker of Dorset:

Troparion, in Tone II

Freely didst thou offer thy life unto Christ, O venerable martyr Wite; for, abandoning the world for His sake, thou didst withdraw to the wilds of Dorset, there to live the angelic life, quenching the fire of the passions with the dew of repentance. Wherefore, as thou didst suffer martyrdom for His sake, thy fame hath spread to all the ends of the earth, and thy holy relics pour forth healings in abundance upon those who ever honour thy memory with love.

Kontakion, in Tone I

Through the virtues and thy love for Christ, O Wite, thou didst transform thy womanhood into manliness, becoming a dwelling-place of God through ascetic struggles; and as a martyr thou art revealed as a fervent intercessor, illumining all with rays of the Spirit, O all-praised one. Wherefore, entreat Christ God, that He grant us the steadfast resolve to fend off all the assaults of the demons.

O ye Christian people, let us praise the martyr Wite, the anchoress of Charmouth, the glory of Dorset and adornment of all England, the boast of Christians and bane of the heathen. For the holiness of asceticism and martyrdom wherewith she was imbued overfloweth even now with the streams of her spring, filling lake and river, pouring down into the waters of the sea, girding England's shores with outpourings of protecting grace.

Holy Mother Wite of Dorset, pray to God for us!

Thank you for this extra information and your interesting OE journal contributions. You are right – sections of church walls and other ruins survive in Reculver, but the twin towers are the only objects of note today. I also know that the two columns and the cross shaft were brought to Canterbury Cathedral. The church gradually turned into ruins due to a number of factors – the encroaching sea, the coastal erosion, high tides, storms, and the abandonment of the village by many residents. I simply didn’t see any point in mentioning these details in a footnote to the article dedicated to St Wite of Dorset, who has a very different story.