St. Congar's sculpture in the Museum of Somerset, Taunton

St. Congar's sculpture in the Museum of Somerset, Taunton

Somerset is a large, picturesque, rural county in south-western England, facing the Bristol Channel: the Mendip Hills lie in the north and the Exmoor National Park in the west. It also has the rolling Blackdown Hills, the Quantock Hills, meadows and woods, along with a large expanse of flat land called the Somerset Levels. Now Somerset is mainly agricultural (dairy and fruit farming), and also has centers of the defense industry and quarrying. This county is noted for its Cheddar cheese and as a major producer of cider in England. Formerly, the weaving and clothing industries prospered.

Such prominent figures as the science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008), the novelist and author of Decline and Fall and Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh (1903–1966), are associated with Somerset. Its rugged moors and charming hills attracted such Romantic poets as William Wordsworth and Robert Southey. Before the English had invaded the whole of Somerset by 710, a host of Celtic saints—monastery builders, preachers, and hermits—had struggled here, and after Somerset had become part of Wessex many early English saints labored on its territory. Such great national saints as Dunstan and Alphege of Canterbury were born in Somerset. This county is home to a number of ancient shrines and sites visited by pilgrims, including the most significant one—Glastonbury. Let us recall two holy Celts who carried out their spiritual labors in this land: Sts. Congar and Decuman.

***

Venerable Congar of Congresbury

Commemorated: November 27/December 10

St. Congar's Church in Badgworth, Somerset (kindly provided by the parish church of Badgworth)

St. Congar's Church in Badgworth, Somerset (kindly provided by the parish church of Badgworth)

Our Holy Father Congar (Cyngar, Cungar, Docco) lived in the fifth to the early sixth century. His Life, composed in the twelfth century in the city of Wells, relates a mixture of events from the lives of several different saints, so ancient traditions are more credible. According to one version, he was born in Pembrokeshire in south-west Wales, and, according to another and less probable version—in the Celtic region of Devon in what is now southwestern England. Tradition holds that the future saint hailed from a royal family (he may have been a relative of the Holy King Geraint of Dumnonia) and his birthplace was Llanungar near St. Davids. We can assume that he was a highly Romanized Briton.

The young Congar, seeking the ascetic, life sailed across the Bristol Channel to what is now Somerset in England, where he founded an influential monastery in a place now called Congresbury (named after him), becoming its first abbot. As is the case with several other Celtic saints, the spot for building the principal monastery was shown to St. Congar by a wild boar.

Congar, one of the most venerated Celtic ascetics of Somerset, lived and served in Congresbury for many years: he always wore a hairshirt, led an exemplary Christian life in permanent fasting and prayer, and his diet consisted only of a small quantity of barley bread that he ate once a day. According to his biographer, “Every day St. Congar used to enter the cold water where he stayed until he recited the Lord’s Prayer three times. Thereupon he would walk back to church, where he spent time in vigils and prayers to God and the Creator of all things. A hermit’s life was particularly dear to his heart; in the ascetic life he imitated St. Paul—the first hermit, and St. Anthony the Great. His diet was so austere that he looked emaciated, and when you saw him for the first time, it seemed as if he had been stricken by fever.”

St. Congar was such an industrious man that in time he turned the once-marshy soil of the part of Somerset where he lived into fertile land. St. Congar performed many miracles in Somerset. For example, one day he thrust his staff into the ground at the churchyard and a huge yew tree sprang up on that spot immediately to provide him with shade, and it grew for many centuries afterwards. The holy man preached zealously across Somerset and also probably in Devon, gradually gathering many disciples around him. With time Congresbury Monastery developed into a flourishing center of monastic life with a large community.

Chancel of St. Congar's Church in Badgworth, Somerset (kindly provided by the parish church of Badgworth)

Chancel of St. Congar's Church in Badgworth, Somerset (kindly provided by the parish church of Badgworth)

Some researchers suggest that St. Congar established a church or even a bishop’s see in Badgworth (or Badgeworth) in Somerset. As the years passed, St. Congar strove for a more solitary ascetic life. Thus, one day, following a vision of an angel, the holy abbot left his community in Congresbury, bid farewell to the weeping brethren and returned to his native Wales. Here he lived as a hermit on a mountain in Glamorgan for some time and may have founded a monastery in Llangennith in Gower Peninsula (some historians believe that this monastery was built by another saint with the same name who lived in Wales, but this version cannot be confirmed). It is believed that Maelgwn, King of Gwynedd, who had a preeminent position among the Welsh kings in the first half of the sixth century and was a great supporter of Christianity both inside and outside Wales, facilitated Congar’s activities in Wales. At a very advanced age, St. Congar together with his relative St. Cybi visited the holy sites on Aran Islands in Ireland and in the Lleyn Peninsula and Anglesey in Wales.

According to a popular tradition, St. Congar reposed during a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Residents of Brittany claimed that the holy man died in Morbihan (south Brittany) on his way back to Britain from Jerusalem. Whatever the truth, the saintly abbot and preacher was buried in the monastery church of Congresbury, where pilgrims went to his shrine throughout the Middle Ages. Alas, it is unknown whether St. Congar was ever consecrated bishop or not.

Our Holy Father Congar was widely venerated in Somerset (where his name was included in all the early calendars) and Wales. Churches that bear his name can be found even in Brittany (eight in all) and Cornwall; the saint probably lived as a hermit on the site of the Cornish village of Lanivet for some time, and churches with a holy well near Bodmin were probably dedicated to him.

St. Andrew's Church in Congresbury, Somerset (photo by Jaggery, Geograph.org.uk) Undoubtedly, the major center for the veneration of St. Congar is the village of Congresbury, where stands the imposing medieval church of St. Andrew. In Saxon times it was known as a minster—this word originally meant a large and important church. However, from about 450 on, the pagan Saxons began their expansion and conquest of Britain, gradually moving to the west. This most likely accounts for the fact that St. Congar had to leave Congresbury Monastery and move to Wales at some point.

St. Andrew's Church in Congresbury, Somerset (photo by Jaggery, Geograph.org.uk) Undoubtedly, the major center for the veneration of St. Congar is the village of Congresbury, where stands the imposing medieval church of St. Andrew. In Saxon times it was known as a minster—this word originally meant a large and important church. However, from about 450 on, the pagan Saxons began their expansion and conquest of Britain, gradually moving to the west. This most likely accounts for the fact that St. Congar had to leave Congresbury Monastery and move to Wales at some point.

After the Britons defeated the Saxons at the Battle of Badon Hill in c. 500, a period of peace followed. But the peace was short-lived: In 552 the Saxons seized Old Sarum, crushed the Britons at Dyrham in 577, and effectively gained control over the entire southern part of England except for some areas in the west. St. Congar had reposed by that time, and in all probability in the late sixth century his monks left Congresbury and scattered across the remaining parts of Celtic world, preaching the Good News, building monasteries, and telling stories about their founding abbot St. Congar. That is why other regions (Dumnonia and Wales) are rich in traditions associated with Congar—they were spread by his disciples.

Merle Chapel inside St. Andrew's Church in Congresbury, Som (from Newcreationchurches.org.uk) In 711, the holy King Ine of Wessex rebuilt the Congresbury church in stone and had it dedicated to the Holy Trinity. When the Welsh Bishop Asser of Sherborne, the author of the biography of St. Alfred the Great, was given the Congresbury Minster in the late ninth century, he wrote that the monastery was derelict. Later, when the Normans rebuilt the original church in the early thirteenth century, they rededicated it to the Apostle Andrew—the dedication it retains to this day. The shrine of St. Congar was kept in the niche of a wall of one of the church side-chapels that bore his name. Now it is called Merle Chapel (after Ann de Merle, who restored it in 1880 and was buried here in 1894), and there is an arched recess on its south wall marking the saint’s former shrine.

Merle Chapel inside St. Andrew's Church in Congresbury, Som (from Newcreationchurches.org.uk) In 711, the holy King Ine of Wessex rebuilt the Congresbury church in stone and had it dedicated to the Holy Trinity. When the Welsh Bishop Asser of Sherborne, the author of the biography of St. Alfred the Great, was given the Congresbury Minster in the late ninth century, he wrote that the monastery was derelict. Later, when the Normans rebuilt the original church in the early thirteenth century, they rededicated it to the Apostle Andrew—the dedication it retains to this day. The shrine of St. Congar was kept in the niche of a wall of one of the church side-chapels that bore his name. Now it is called Merle Chapel (after Ann de Merle, who restored it in 1880 and was buried here in 1894), and there is an arched recess on its south wall marking the saint’s former shrine.

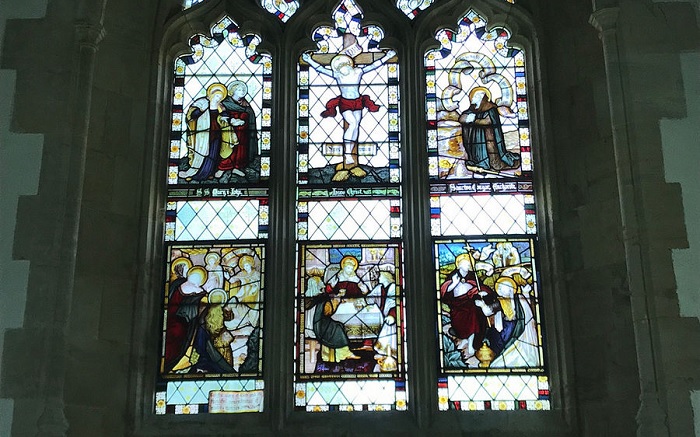

Alas, the influx of pilgrims to St. Congar’s relics after 1,000 years stopped forever under Henry VIII: his shrine was destroyed (its remains may have been built into the church’s east wall) and the relics lost forever. Currently the church reportedly has an icon of St. Congar, virtually the sole reminder of this great saint’s achievements inside this large ancient church. The current church was consecrated in 1215: it has features of the Early English and Perpendicular Gothic styles. Among the church’s treasures are the centuries-old double piscina (a stone basin for draining water used for Holy Communion) in the sanctuary, with a stained glass above it depicting the four patron-saints of the British Isles (St. George the patron of England, St. David the patron of Wales, St. Patrick the patron of Ireland, and St. Andrew the patron of Scotland); an East Window, with scenes from the Life of Apostle Andrew etc; and the screen—all that remains of the medieval and once brightly adorned Rood Screen, with carvings of a vine and the grapes, symbolizing Christ and His followers. The church tower is of the fifteenth century and is topped by a gilded weather-rooster (a common feature in English churches), which symbolizes the thrice-repeated denial by Peter.

The beech with remnants of St. Congar's yew tree in Congresbury, Som. Photo: Congresburyhistorygroup.co.uk Outside the church, in the churchyard grows an enormous and very old beech tree. It is notable for the fact that once it grew around the miraculous yew of St. Congar (mentioned above) and eventually overtook it. However, remnants of that mysterious yew can still be traced—they are literally imbedded in the beech trunk and can be distinguished by red bark. Thus a tiny bit of the fifth-century miracle of St. Congar physically survives to this day. On or close to St. Congar’s day the church and the village of Congresbury organize large-scale celebrations among the parishioners and residents. Next to the church there is the fine thirteenth-century priests’ house, which once accommodated clerics who entertained the pilgrims visiting St. Congar’s shrine.

The beech with remnants of St. Congar's yew tree in Congresbury, Som. Photo: Congresburyhistorygroup.co.uk Outside the church, in the churchyard grows an enormous and very old beech tree. It is notable for the fact that once it grew around the miraculous yew of St. Congar (mentioned above) and eventually overtook it. However, remnants of that mysterious yew can still be traced—they are literally imbedded in the beech trunk and can be distinguished by red bark. Thus a tiny bit of the fifth-century miracle of St. Congar physically survives to this day. On or close to St. Congar’s day the church and the village of Congresbury organize large-scale celebrations among the parishioners and residents. Next to the church there is the fine thirteenth-century priests’ house, which once accommodated clerics who entertained the pilgrims visiting St. Congar’s shrine.

Congresbury itself is situated some ten miles south of Bristol, and the River Yeo goes through it. There is an ancient hill called Cadbury Hill less than a mile from the village. Many artefacts can be found there as this is a hill fort where people lived in the Iron Age, namely the Dobuni tribe who inhabited the Cotswolds. The settlement was abandoned during the Roman occupation of Britain in the first century A.D.: there was certainly a Roman villa nearby and a pagan Roman temple was built at Henley Wood just to the north of the hill. Even before the collapse of the Roman Empire the pagan place was abandoned and Christian burials appeared on the hilltop over the pagan graves.

The hill fort had a new lease of life after the departure of the Romans from Britain in 410, and the place thrived for about three centuries. The inhabitants of the hill fort were wealthly and trade flourished. Many amphorae from the Mediterranean were found here with no fewer than sixty glass vessels that were produced locally. There was certainly a Christian community on this site from the sixth century on, and it is quite possible that St. Congar ministered to the Christians living in the hill fort or even built his main monastery on its top. Thus the settlement of neighboring Congresbury grew, and apart from the main monastery church there was a church of the Archangel Michael that must have been used for burials (according to Elizabeth Rees, An Essential Guide to Celtic Sites and Their Saints).

Stained glass above the altar of St. Congar's Church in Badgworth, Som (kindly provided by the parish church of Badgworth)

Stained glass above the altar of St. Congar's Church in Badgworth, Som (kindly provided by the parish church of Badgworth)

The fourteenth-century church in the village of Badgworth, mentioned above, in central Somerset near the town of Axbridge, is dedicated to St. Congar. Its oldest part is the north chapel, and it is a mixture of the Perpendicular and Decorated Gothic styles. The nave, tower and windows are of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. One of the gems is the chancel floor with its patterned design. The stained glass window above the altar is mainly dedicated to the life of Christ, but its right top panel is dedicated to the heavenly patron—St. Congar; it bears the inscription: “Sanctus Congar, Anchorite.” Some of the church fittings predate the current building and may have been preserved from the previous church. The font in the nave is from the thirteenth century, some benches with poppy heads are from the fifteenth century, and the pulpit is Jacobean. The church stands on the edge of the village, and a prominent view of it opens from the fields nearby (this information kindly provided by St. Congar’s parish, Badgworth).

The Museum of Somerset in Taunton, the county town of Somerset, has a sculpture of St. Congar. It was once housed in the church of Congresbury and was discovered and identified by the archeologist Michael Aston (1946—2013).

St. Congar's Church in Llangefni, Anglesey

St. Congar's Church in Llangefni, Anglesey

A beautiful church in the Welsh town of Llangefni on Anglesey is dedicated to our saint. Originally the town was called “Llangyngar”—that is, “church of St. Cyngar”. The church dates back to the nineteenth-century and stands at the entrance to the Dingle nature reserve just north of the town. The parish church in the small village of Hope in Flintshire in northeast Wales close to the English border is dedicated to St. Cynfarch (who lived in the fifth century) and St. Cyngar. Finally, the parish church in the village of Borth-y-Gest in the town of Porthmadog in the Welsh county Gwynedd is dedicated to St. Cyngar.

***

Venerable Martyr Decuman of Dunster

Commemorated: August 27/September 9

St. Decuman's Church in Rhoscrowther, Pembrokeshire

St. Decuman's Church in Rhoscrowther, Pembrokeshire

St. Decuman, whose Life was written as late as the fifteenth century in Wells Cathedral, was born in the sixth or seventh century to a noble family in what is now Pembrokeshire in south-western Wales. His supposed birthplace is the Welsh village of Rhoscrowther (the original name: Llandegeman, meaning “Decuman’s church”), and the local parish church is dedicated to him to this day. Deciding to abandon secular life, the young Decuman left South Wales and travelled to north Somerset. According to tradition, the man of God came to this region across the Bristol Channel on a raft, accompanied by a cow that supplied him with milk and was his faithful friend for many years. The ascetic settled on the site of today’s tiny village of Dunster near the Bristol Channel, close to the north-eastern edge of the high moorland of Exmoor (nowadays it is a National Park and mostly a grazing ground for ponies, sheep and red deer).

Wooden angels on the wagon roof of St. Decuman's Church in Watchet, Somerset (from Uksouthwest.net)

Wooden angels on the wagon roof of St. Decuman's Church in Watchet, Somerset (from Uksouthwest.net)

Our Holy Father Decuman became a preacher and began to heal the locals from various illnesses. In time the saint moved to what is now the small harbor town of Watchet on the coast of the Bristol Channel, where he led a strict ascetic life. Decuman prayed to God and sang psalms day and night, lived on herbs and roots, drank water, only allowing himself some milk on feasts and non-fast days. After many years of unceasing prayer the anchorite received the crown of martyrdom. According to the most popular version, he was slain by a malicious pagan, who beheaded him while the saint was standing in prayer. The medieval sources give 706 as the year of this tragedy, while it well may have happened much earlier—in the sixth century. According to legend, St. Decuman instantly took his severed head with his hands, washed it in a spring, and miraculously reconnected it with his neck! The local people who took pity on him helped the ascetic build the church, after which he died peacefully. Interestingly, the same late medieval legend (with some variations) is described in the Lives of a number of other beheaded Celtic saints.

The people of Somerset were so impressed by Decuman’s holy life and stricken by his martyrdom that they began to venerate him as a saint right after his death.

St. Decuman's Church in Watchet, Somerset

St. Decuman's Church in Watchet, Somerset

The church in Watchet stands to this day; though of course it was rebuilt more than once after St. Decuman’s martyrdom. It is dedicated to St. Decuman, the holy preacher and martyr, and his wonderworking relics rested here for many centuries. The current church dates back to the fifteenth century. It has a large and wide chancel (which predates the rest of the building), which was enlarged over its history and the saint’s relics were enshrined in it. The chancel floor notably contains some fine thirteenth-century tiles, which were created at the neighboring Cleeve Abbey—now it is the most complete and relatively unaltered medieval monastic complex in England. No trace of the martyr’s shrine survives, and almost the only reminder of the holy man at this church is his small statue in a niche on the south side of its bell-tower. Among the numerous internal gems let us mention the carved wooden rood screen, stretching the width of the church nave, with some traces of medieval paint, and the thirteenth-century carvings on the wagon roofs with figures of angels on them. The church stands on top of a hill overlooking Watchet, and it is believed that the original church stood on Daw Castle—the Iron Age hill fort on a sea cliff nearby—but it did not survive coastal erosion.

St. Decuman's Church interior, Watchet, Somerset

St. Decuman's Church interior, Watchet, Somerset

Below, on a steep slope of the hill, is the miracle-working St. Decuman’s well. According to one version, it appeared on the spot where his severed head fell (or, alternatively, it had existed before St. Decuman’s arrival, but it became holy by the touch of the saint’s blood). Its water used to flow downhill into two basins before going into the ground. A medieval document reads: “The fountain of St. Decuman is sweet, healthful and necessary to the inhabitants for drinking purposes.” Pilgrims went to this well till the sixteenth-century Reformation, and by the mercy of God this well was restored not long ago. Pilgrims again visit this holy and pure source, and cases of healing occur nowadays. The main pool is covered by a well-house, and the second pool runs down the slope. The well is set within a beautiful and secluded garden—an appropriate place to linger and pray in. St. Decuman has been venerated as the patron-saint of Watchet and of the historic parish of St. Decumans.

St. Decuman's well in Watchet, Somerset (photo by Sarah Charlesworth, Geograph.org.uk)

St. Decuman's well in Watchet, Somerset (photo by Sarah Charlesworth, Geograph.org.uk)

Remarkably, Watchet is associated with the great English poet and philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772—1834), author of lyrical ballads and such poems as “Christabel”. Coleridge, whose home was in a neighboring village, was inspired by the view of the harbor from St. Decuman’s Church and composed his famous poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”.

Outside Watchet, other major centers of veneration of St. Decuman were Muchelney and Wells in Somerset. This saint is still venerated in Somerset, South Wales and in several places in north Cornwall near Helstone. The existence of churches dedicated to St. Decuman in Somerset, Cornwall and Wales indicates that his disciples spread his veneration and were active in these regions, although it is not ruled out that St. Decuman himself made missionary journeys across the West Country.

St. Decuman's Church ruins in Killag, Wexford

St. Decuman's Church ruins in Killag, Wexford

St. Decuman is even venerated in the Irish county of Wexford—in the province of Leinster in the southeast Irish Republic. There used to be dedications to the saint in Killag, Killiane, and Ballyconnick; now all of them are in ruins.

Holy Fathers Congar and Decuman, pray to God for us!