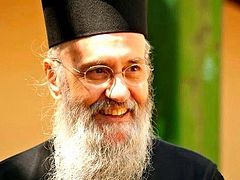

His Eminence Metropolitan Hierotheos (Vlachos) of Nafpaktos, who has written several articles on the current Ukrainian issue, most recently published his own proposal for how to move forward. On Tuesday we published a response from Dr. Demetrios Tselengidis of the University of Thessaloniki, and today we offer a response from our contributor Dionysius Redington.

***

Metropolitan Hierotheos (Vlachos) of Nafpaktos is a well-known Greek theological writer, associated particularly with the idea of the Church as a hospital for sinners. His book Orthodox Psychotherapy, while perhaps somewhat disappointing in its refusal to seriously contrast hesychastic wisdom with Western scientific methods (merely rejected out of hand), is nevertheless a true modern spiritual classic, and one of the best available summaries of the ascetical sciences. Many people have reportedly been led to repentance and spiritual awakening by reading it.

Metropolitan Hierotheos is generally regarded as a leading theological conservative. This reputation came to the fore during the recent Council of Crete, in which he bravely rejected some of the language advocated by the Ecumenical Patriarch and his associates. In particular, Metropolitan Hierotheos objected to calling non-Orthodox religious bodies “churches,” on the grounds that there is only one Church. While it could perhaps be argued that this was not the most pernicious instance of the Council’s occasional ecumenistic tendencies (and indeed was merely an attempt at politeness), the Metropolitan’s opposition to it demonstrated his willingness to take a stand for the Truth, even when this brought him into conflict with the Ecumenical Throne.

It was therefore a surprise to many that in the recent ecclesiastical conflict, supposedly over Ukrainian autocephaly though with origins in fact much deeper, Metropolitan Hierotheos has championed Constantinople’s position with an eloquence and fervor sadly rare on the other side.

In a recent article, the Metropolitan offers his suggestion for defusing the crisis, which he presents as solely a disagreement over the means of granting autocephaly. I will not repeat the specifics of his proposal here. Rather, I will suggest that it is founded upon two fallacies, one more serious than the other, and that these fallacies render the entire proposal moot.

The less serious fallacy is one by no means unique to Metropolitan Hierotheos or even to his side of the argument; it seems to have infected the entire mindset of the institutional Orthodox Church leadership since at least the early 1900s. This is the belief that a Council of the Church cannot actually decide anything in session, but must be convoked with a pre-arranged agenda to be endorsed, or one might say rubber-stamped, by the assembled hierarchs. The insistence by all parties on such a rigged Council is obviously the reason that the Church spent the entire twentieth century planning a Council which has not yet been held. (The Council of Crete was the closest attempt so far at an actual realization of it, but clearly an unsuccessful one.)

While it is true that some Church Councils, genuine as well as “robber,” came together with an agenda and overall conclusion fixed in advance, not infrequently by the imperial bureau of religion, it is equally clear that others involved real debate and controversy. Humanly speaking, they might have easily gone “either way.” The Creed was hammered out in the course of two Councils, and the final result was not identical to the initial proposals. A Council (ideally) is, to use the sort of scientific analogy favored by Metropolitan Hierotheos, an instrument for discovering God’s Truth. If it operates correctly, the hierarchs assembled (and all later Orthodox) will be able to perceive the Truth; if not—if, as it were, the lenses of the microscope are incorrectly focused, or even removed—then the Council is a Robber Council and the Truth remains hidden. To suggest that the conclusions of the Council must be agreed upon in advance—that “there has to be ... a proposal on which the majority of Orthodox Churches agree, and which, of course, the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Church of Moscow accept”—is absurd, as is the Metropolitan’s contention that “if there is no convergence of opinions beforehand on a specific proposal ... there is no reason for a Pan-Orthodox Council to take place.” On the contrary, the less agreement, the more urgent the need for a Council: Surely the Orthodox spiritual physician most needs a microscope when the pathogen is invisible to the naked eye!

This is then a fallacy, but it might still be worth discussing Metropolitan Hierotheos’ suggestions as a proposal to be placed on the agenda for discussion, rather than as a pre-approved consensus without which a Council may not occur. Unfortunately, they are completely beside the point, and any discussion of them appears to me essentially a waste of time. This is because they entirely mistake the nature of the pathology currently affecting the body of believers.

“Autocephaly and the means by which it is granted” may be, and no doubt is, a problematic subject, but it is not an urgent one at the moment. The crisis that has resulted in the interruption of communion between Moscow and Constantinople is not simply about who has the right to do what and whose authority ends at which geographical boundary.

I personally do not care who makes or blesses the Chrism used in my parish, or whether my country (the world’s most powerful empire, as it happens) has an autocephalous Church. What is it to me whether the leader of my local church be a fellow citizen, or the nominal pastor of a dying Greek neighborhood in Turkey, or the spiritual leader of an apparently hostile country whose nuclear missiles are pointed at my home? I care only whether he be an Orthodox Christian who (whatever his personal failings, personal political views, and eccentric personal theologoumena) proclaims as dogma the Gospel of Jesus Christ and that alone. If any Ukrainians, on either side of the autocephaly issue, feel otherwise, so much the worse for them.

The issue at stake in the present crisis is most emphatically not the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarch, nor the alleged imperialist scheming of the “Muscovites,” nor the “right” of Ukrainians to have a national Church. The issue is the extraordinary neo-papist claim of Patriarch Bartholomew that he is “first without equals.” It is the Phanar’s contention that the Orthodox Church “cannot exist” without the Ecumenical Patriarchate. It is the view that the primacy of the Primus in a group of Orthodox bishops reflects the monarchy of God the Father.

Are these mere theologoumena?[1] Clearly, no Council has discussed them, either because they are novelties or because no-one has drawn any practical conclusions from them. The sole meaningful task of any proposed Church Council must be to decide whether these propositions of Patriarch Bartholomew and his circle—I think Archbishop Elpidophoros of America is more their author than is the Patriarch himself—are true, false, or merely acceptable opinions.

If they are true, then the Patriarch’s actions are entirely justified, because he and his predecessors hold, and have held since sometime in the Middle Ages, the powers claimed by the Roman Pope (and more). If they are false, then the urgent issue is for the Patriarch to admit in public that he was in error, and to repent, after which the matter of Ukrainian autocephaly can be discussed along the lines proposed by Metropolitan Hierotheos. Finally, if the Council determines that “primus sine paribus” theology is neither dogma nor heresy, Ukraine will be only one of many places where Constantinople’s self-image will clash with that of other Local Churches with a different view, and resolutions will be slow in coming.

Lest this response be seen as somehow unduly pro-Russian, I will mention another of Metropolitan Hierotheos’s remarks: “[F]rom time to time various ecclesiastical illnesses appear, which I would describe as dysfunctions of the synodical and hierarchal regime of the Church, such as the theory of the Third Rome, which aim to overturn the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils.” Although I disagree with this assessment of the Third Rome theory, I do agree that this should probably be explicitly on the agenda of any Council. Clearly any attempt to limit extraordinary jurisdictional claims by Constantinople must not be made in the interest of advancing extraordinary claims from other Sees.

Metropolitan Hierotheos also makes some “practical” suggestions to be implemented before any Council, such as resuming communion and adding prayers for Patriarch Kirill in Constantinopolitan churches and for Patriarch Bartholomew in Russian ones. These would be sensible in the context of a mere territorial or even legal dispute, since, as the Metropolitan observes, “[t]he sacrament of the Divine Eucharist, which is a sacrament of unity, and the sacrament of Confession, cannot be used to exert pressure on other Churches, particularly on matters of secondary importance.” Unfortunately, it is not clear that we are dealing with a matter of “secondary importance;” it seems quite possible that “primus sine paribus” is a true heresy (or, I suppose, that its rejection is a true heresy). If the Ecumenical Patriarch wishes to make an irenic gesture which would make possible the resumption of communion, he should declare explicitly that, until a Council decides on the matter, the claims on which he bases his interference in Ukraine are simply theologoumena, and not binding upon believers.

Metropolitan Hierotheos quotes at some length from the highly rhetorical concluding section of St. Basil the Great’s On the Holy Spirit, written in the decade before the Second Ecumenical Council. The significance of this quotation in the context is unclear. The Second Council addressed various administrative issues and established Constantinople as second to Rome in the Orthodox world, but its main theological point was the condemnation of Macedonianism,[2] a serious heresy and the target of St. Basil’s treatise. One can imagine St. Basil making proposals similar to those of Metropolitan Hierotheos in an attempt to end the Meletian Schism,[3] but one cannot imagine him compromising with the Pneumatomachi. It is the latter case which the present situation more closely resembles.

Holy Basil the Great and Amphilochius of Iconium, pray to God for an end to the present schism, for the Patriarchs of Constantinople and Moscow, for the Metropolitan of Nafpaktos, and for us all!