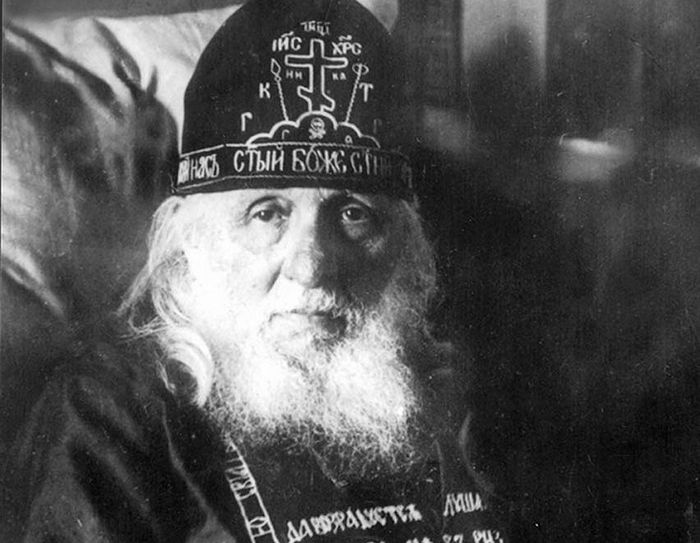

This description of Hieroschemamonk Alexiy (Soloviev, January 17, 1846–September 19/October 2, 1926) of St. Zosima Hermitage was written while the elder was still alive, by the distinguished Bishop Arseny (Zhadanovsky) of Serpukhov, the abbot of Chudov Monastery in the Moscow Kremlin. Bishop Arseny is also unofficially among the new martyrs and confessors of Russia, as he was executed at the Butovo firing range just south of Moscow for serving secret Liturgies. St. Alexiy was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000.

Bishop Arseny made it his duty to write about contemporary ascetics of piety. In his words, “In this age, there is a strange supplanting of religious understanding. Eccentricity is seen as the highest spiritual power, ordinary sentimentality as contrition and love, the effect of personal magnetism or even simply the influence of dark powers as clairvoyance, the gift of miracles, and the gift of consolation. The true bearers of the Holy Spirit remain somehow unnoticed” (from one of his religious brochures).

Hieroschemamonk Alexiy, in the world Feodor Alexeyevich Soloviev, was born in Moscow to a long line of priests. At the end of his studies in the Moscow Theological Seminary he was married and sent as a deacon to the Church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi, by the Moscow River. Widowed after two years, Fr. Alexiy began thinking about leaving the world and joining a monastery, but his close ones persuaded him not to abandon his son but to first raise him, and only then carry out his intentions. After intense prayer and consideration Fr. Alexiy agreed, and lived for the next twenty years in Moscow, impatiently waiting for his son to finish his education, which he received in the Higher Technical School.

The elder’s final place of service in Moscow was the great Dormition Cathedral, where he ended up as a priest for his outstanding bass voice. The ancient holy site in the Kremlin bore a preparatory significance for Fr. Alexiy’s entrance into monasticism.

The elder spoke of it thus:

“I would sometimes enter the cathedral at three o’clock in the morning to serve the Matins, and a reverent awe would seize me… Silence all around. Moscow is still sleeping… In the mysterious semi-darkness of the church, the entire history of Russia would arise before you… The miraculous protection of the Mother of God in her Vladimir icon during the years of calamity, the shadows pass by of Moscow’s holy hierarchs, the guardians of the Fatherland and pillars of Orthdoxy… And I wanted then to pray for Rus’ and all her faithful children, to dedicate myself wholly to God and never return again to this vain world.”

No sooner than his son had graduated from the institute, Fr. Alexiy left Moscow and hastened to ensconce himself in a monastery. It was his desire to find a solitary monastery, where the gossip of everday life would not penetrate and where monks truly saved their souls in labors, simplicity and prayer. In those days, such was considered the Skete of the Holy Paraclete.1 There did our holy elder direct his steps. Along the road he visited the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra to ask a blessing from the abbot, Archimandrite Paul. The latter, however, instead of the Paraclete offered him the St. Zosima Hermitage.2 Accepting it as God’s will, Fr. Alexiy entered that monastic community.

He spent his first years there as a novice: He sang on the cliros, went to the trapeza, taught the Law of God to the brothers, and took his turn with the hieromonks serving in church as the least of the priests. At times he even had to accept criticism from certain hotheaded monks, especially from the choirmaster.

I recall Fr. Alexiy when he was still conducting his obedience on the cliros. His rare, velvety bass embellished the entire choir and gave the St. Zosima singing a certain special tone. Meanwhile our abba quickly progressed in monasticism and was soon appointed father-confessor of the monastery, and later as the elder of the brotherhood.

Fr. Alexiy’s special character traits were his sociability, accessibility, and attentiveness to all. Both old and young, educated and illiterate, all felt that Batiushka was never burdened by anyone, but would show a lively interest each one’s fate. More than that, he would take upon himself the sorrows of others, because in his conversations with them he would be tormented, thinking about how to help and relieve their suffering. Could that be why the elder has heart problems—from his co-suffering with the people who came to him?

Yes, Fr. Alexiy’s sympathy for those seeking his counsel is amazing. He can’t let a person go before that person has calmed down and spilled all that has collected in his soul. His striving to always benefit those who come to him causes unrest in him—it would suddenly seem to him that someone had remained displeased and not at peace. Then the elder would be tormented and pray that his words might not serve to harm that person in any way. So strong is Fr. Alexiy’s desire to save others.

Word of his experience in spiritual matters and unusual accessibility gradually spread far and wide. Muscovites especially began flocking to him. It came to the point where after receiving people non-stop without rest for whole days, he began to weaken and have heart attacks. These conditions, and then also his spirit’s inner demands made him withdraw temporarily into his cell. All who knew Fr. Alexiy at first had difficulty resigning themselves to this fact; many were perplexed as to why Batiushka, who had such a sociable character and was of such great moral benefit to people, would resolve himself to such a podvig.

One of his spiritual daughters related to us:

“Besides my personal sorrow over the wise elder’s departure from us, I was feeling some kind of burning pity for him. It seemed to me that reclusion would be hard for him. It’s true, I knew that solitude would unite him with Christ, to Whom he had given his heart and mind, but nevertheless, I thought that voluntary confinement did not correspond to Fr. Alexiy’s personality. At our farewell my heart wrenched with pain; I nearly murmured, not knowing against whom, and was even ready to think that it wasn’t the elder himself but someone else who was laying such an unbearable, cruel, and unnecessary cross upon him…”

Besides his gift of eldership, Fr. Alexiy had many remarkable qualities of soul. He was a man of his word, always scrupulously and eagerly carrying out his obediences and responsibilities. The entire order of his life is precisely governed by the Lavra’s administration, and he considered it impossible to violate it.

The elder’s usual answer to his spiritual children when they tried to extort something from him was, “This was not allowed to me by my instructions.” Here is another striking example of that same reliability.

In 1917 he was present at the Local Council in Moscow. It was October, and there was shooting in the streets. Peaceful civilians were staying home. But Fr. Alexiy was setting out from Chudov Monastery to the diocesan house3 for another session.

When we tried to talk him out of going, he said, “And what will the holy fathers say to me? The schemamonk didn’t come—he was afraid of death. I’ll be ashamed to receive the daily minutes recorded by the Council members.” So Fr. Alexiy goes, but he is sprayed with bullets, so that he is forced to return home. I remember that we all gave thanks to God Who miraculously saved our elder’s life.

Another no less outstanding trait of Fr. Alexiy’s spiritual countenance is love, which as we noticed came to the surface in his strong desire to save his neighbor. This same feeling made him pray so fervently for his spiritual children. He comes to the Liturgy an hour or more before the beginning in order to commemorate everyone he knows and remove a particle of the prosphora for them.4

The elder placed love higher than fasting and prayer.

One novice asked him, “Batiushka, what should I do? I live in my cell with a brother. At night I want to pray, but no matter how quietly I try to do it, he wakes up and in that way I disturb him. Should I continue with my prayer rule or would it be better not to disturb my cellmate’s sleep?”

“I would advise you,” said the elder, “not to disturb your brother, for love is higher than all.”

Fr. Alexiy is capable of self-sacrifice. Once his dedicated and beloved spiritual son, Archimandrite S. I., fell ill with typhus. So, what did he do? The elder prayed, “If Fr. S’s illness is unto death, then bless me, Lord, to die in his place, and let him go on living here on earth and glorifying Thy name…”

Our abba’s pity even extends to the animals and insects; he considers it a sin to kill any living creature, and when for example a mouse is caught in a mouse trap he asks his cell attendant monk Makary not to kill it but to take it to the forest far away from their home and let it go…

Fr. Alexiy is a faithful son of the Orthodox Church. Just as a photographic plate receives everything exactly, so also does our elder, illumined by the Light of Christ, correctly and profoundly preserve the true faith with his mind and heart. Instead of testing Church views according to canons and books, it is enough for his spiritual children to ask the elder’s opinion, and they can always receive unerring explanations of one or another question.

We must note that every ascetic and spiritual orator has his own favorite themes, around which his thought and feelings turn. Our abba was always disturbed by contemporary unbelief and apostasy. He talks about these things continually, pointing out one or another side of this phenomenon. There was a time when he spoke a lot about Tolstoy and his followers, and then about Baptists, later about Theosophy, spiritualism, occultism, and other such things. In the moral sphere he gave much attention to the destructive harm that secret vices cause to young people.

Fr. Alexiy is also amazing for his humility. An enlightened and spiritually experienced man, he could have occupied a high position in the Church, but he was satisfied with the modest vocation of a monastery elder. Life in the desert community, reclusion, and instructions from the Lavra fully guarded him from any leadership positions and hierarchical elevations.

The same humility makes the abba say to each and everyone: “I know nothing; I’m sewn with hay.” He gets angry when people call him clairvoyant or consider him worthy.

Treating all those of higher rank than himself with respect, he also strives never to judge anyone and teaches his spiritual children to do the same. His humility is so strong that it seems that Fr. Alexiy is ready to ask forgiveness from everyone and would bow to the lowest person’s feet without a second thought. He addresses his cell attendant, Monk Makary, in the second-person formal, and asks him permission and as if advice in everything. In fact, sometimes the elder displays vainglory, only of a very particular kind, related more to the worthiness of other people than of his own. For example, he loves to glory in his distinguished spiritual children.

“After all, you know,” Batiushka shares with his interlocutor, “that N. is my spiritual son. What a son I have!”

Fr. Alexiy is, finally, an example to all of a monk who has conducted a very attentive spiritual life. He vigilantly watches the movements of his thoughts and feelings and gives an account of everything once a week at confession. True, the elder reads [his confession] according to the printed rule, but while most of us limit ourselves to a simple enumeration of sins, Fr. Alexiy after each named deed stops to indicate how guilty he is of it himself. That is why his confessions are always long. We happened to be Batiushka’s confessor for almost an entire year, when he was present in Moscow for the Council, and we received a great lesson from it.

Fr. Alexiy had to live through a seven-day confinement in the basement church of St. Hermogenes5 during [the shooting of the Kremlin, October 27–November 3, 1917].

Having received the monastic tonsure with the name Alexiy, in honor of the Metropolitan of Moscow, he had never visited [the relics of] his patron saint during twenty years of never leaving St. Zosima Hermitage, and now thanks to the Local Council, he was to share with the monks of Chudov Monastery the most difficult and dangerous moment of their life, when each was a hair’s breadth from death. The great abba’s presence with us lifted our spirits, brought us calmness, and routed all fear.

I receive what I deserve according to my deeds. Remember me, O Lord, in Thy Kingdom. O Lord, may Thy holy will be done on me a sinner, now and unto the ages. O Lord, I am Thy slave and the work of Thy hands, whether I want it or not, I am under Thy authority. Do with Thy creation according to Thy will and according to Thy great mercy. Glory to Thee, O Lord, for all the things that Thou hast brought upon me. Glory to Thee! Thy judgment upon me is just, I who deserve all temporary and eternal punishments. I thank Thee and glorify Thee, O Lord and God, for these small and insignificant sorrows that Thou dost allow upon me by Thy all-good and most wise Providence, by which Thou dost relieve me of my unknown passions, and lighten my answer at Thy Dread Judgment, and by which Thou dost redeem me from the eternal torments of hell.

O our Lord God, forgive us all our sins, voluntary and involuntary. May Thy holy will be done in everything for us sinners. Make us worthy to submit in all things, steadfastly and with peace of soul, to Thine all-good and most wise will and to fulfill it. Vouchsafe this also to our close ones and all Thy people, for Thou knowest all things that be unto our true benefit, O Thou Who art all-merciful and blessed unto the ages. Amen.