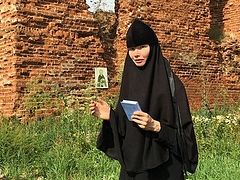

Abbess Elena (Zolotukhina) of the Spassky Convnet of the Voronezh Metropolia spoke with a correspondent of “Monastery Bulletin” about monasticism, her path to the monastery, and the difficulties faced by modern man seeking the monastic life.

—Mother Elena, the monastery in Kostomarovo was opened in 1997. When they appointed you as abbess, the first stage of restoration was already completed…

—Mother Elena, the monastery in Kostomarovo was opened in 1997. When they appointed you as abbess, the first stage of restoration was already completed…

—Yes, I arrived in 2007; the monastery was already active for ten years by then. Before me, the abbess was Igumenia Seraphima (Ivanova). She wasn’t able to manage the monastery because of her health, and with the blessing of Vladyka Sergei, Metropolitan of Voronezh and Borisoglebsky, they appointed me as abbess and transferred me from the Voronezh St. Alexei-Akatov Monastery. Of course, the most difficult stage of restoration went to Mother Seraphima, because it was a completely empty place at that time, with abandoned, dilapidated, and even desecrated cave churches.

You could say I simply continued to labor here with the sisters—with those who remained and those who came later. We are continuing to create a monastic community on this amazing, holy place, which attracts great attention with its extraordinary beauty. But I don’t think it would attract such attention if there weren’t an active monastery here, if there weren’t prayer, if the sisters weren’t trying to walk the path of salvation.

—They say that Spassky Monastery in Kostomarovo is an historical monastery. Why?

—Because no written evidence has been preserved, or, in any case, has been found yet, about the time of the monastery’s origin or its founders; we have only legends and hypotheses. More or less accurate information appears in the post-war period, when a community was organized in the caves, but it wasn’t a monastery, and its activity was soon terminated. But about how the caves were created, there is only conjecture. According to one hypothesis, there was an ancient monastery here, but according to other information, it appeared in the twelfth century, and a third version Is that the caves were dug by local peasants at the end of the nineteenth century…

We are of the opinion that, in fact, they started to make the caves in ancient times, and precisely as churches. This can be judged by analogy with the neighboring Divnogorie, Belogorie.1 They have documentary evidence there of the time of the emergence and existence of the monasteries, but to find out what was on the site of the Kostomarovo caves is a matter for the future.

—Are there many pilgrims to the monastery?

—In the summer we spend most of our energy enabling pilgrims to visit our cave churches; the sisters are busy in the church store and in the pilgrim’s trapeza. Since the cave churches are cold and damp, and there has to be someone on duty, when groups of pilgrims come we have to replace the sisters throughout the day. We have one small guesthouse on the territory of the monastery, which mainly houses clergy when it’s their turn to serve, as well as workers who come to help the monastery. There’s another hotel for pilgrimage groups outside the monastery, in Kostomarovo, a five minutes’ drive.

—Sometimes we hear that pilgrims disrupt the inner life of a monastery. What do you think about that?

—I don’t hear such complaints from the sisters. I’ll say this: No one interferes with us more than we do ourselves… There are monasteries that do bear a very heavy burden from pilgrims. Because the place is “exotic” here, we get completely different people, including many non-Church people, who don’t always understand where they are. Nevertheless, these people sacrifice something for the restoration of the monastery, and most importantly—they touch the sacred here. Therefore, the sisters really try to do everything so that pilgrims would feel the warmth of this place, so they wouldn’t go away empty.

We try to receive everyone with respect. Of course, we don’t get such a flow of people like at Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra or Diveyevo, but about 40,000 people visit us every year—mainly on weekends, feast days, and in the summer. It is a little hard then, but parishioners from the surrounding villages and the regional center come to help—we have such constant helpers… The Lord measures our strength and gives the opportunity to get some rest. There are basically no pilgrims in the winter.

—How is the spiritual life of the monastery arranged? Do the sisters have time for prayer in their cells? Do you hold talks with the sisters?

—Liturgy is served every day. There are three priests in the monastery, and the sisters go to confession mostly before Communion. If there is a need for an additional confession, they can choose a time and go to whichever priest is serving then, or to whomever they are more disposed. If they have some kind of questions for me, then I am also available. I believe there is time for the sisters to have cell prayer—we do everything according to our strength. The obediences are the usual, as everywhere.

We have talks, perhaps not as often as we would like, but we gather for conversations or to read together. We mainly read Patristic literature. Also, after the monastic conferences, we get acquainted with the most interesting reports concerning the pressing issues of our life. Of the most memorable, for example, was the presentation of Abbess Domnika (Korobeinikova) about how to bear obediences with love, or Vladyka Arseny of Svyatogorsk. A series of books from Archimandrite Aimilianos (Vafeidis) [of Simenopetra—Trans.] recently came out, which very deeply reveal the problems of monasticism; we discuss them after reading them, based on our inner life in the monastery. During meals, we don’t so much read hagiography as Patristic literature, in the hope that the sisters, hearing something useful for themselves, will want to take the book from the library and read more carefully.

—Mother, you raised the issue of monastic conferences. Are they useful, in your view, or do they just distract monastics from the rhythm of the monastic life?

—I think they’re very useful. Probably everything has its own time, but I think if we had had this chance earlier—to get together and discuss our common problems—we could have avoided significant mistakes. Communication is very important. In many cases it becomes clear that what’s bothering you isn’t just your personal difficulty, but is common to our monastic life and the arrangement of monasteries.

A good topic is traditions in modern conditions. We often hear that the ancient traditions are inapplicable to our times. But at the conferences, the participants share about how these traditions can be implemented now—it’s very important. What the Holy Fathers said in ancient times about monasticism is still the way for us. How we travel this path, crawling or lying down (but al least in the right direction), depends on us—because if we simply leave the path pointed to by the ancient Fathers, along which we move towards salvation, there will be only turmoil and confusion. Yes, of course, our powers are not commensurate with theirs, but we have the advantage: They have already expounded everything for us, pointed out the hidden pitfalls, what should be feared… I think it’s better to crawl along the correct path than to run at rapid fire pace in the wrong direction.

—Do the sisters who come to the monastery today differ from those who came, let’s say, twenty years ago? What is modern man in monasticism like in general?

—You know, I don’t see a big difference. Maybe they’re just physically weaker, unhealthier. The people coming to us are, as a rule, not so young, but are already developed personalities. The difficulty lies in the fact that you have to know yourself on this path. In the world, you live a scattered life, and external circumstances don’t allow you to see yourself as you are. A man in the world has the chance to change activities, a moment of some psychological relief: At work I’m alone, at home it’s a little different… In the monastery, you’re constantly in the same conditions, with the same people, and you don’t have this loophole. You can’t hide yourself here very long, even from yourself, and you start learning many interesting things about yourself. The first thing I hear from most of the sisters is, “Something happened to me; I wasn’t so bad before!” Yes, you were good, because in the world there is an opportunity somewhere to be good. But in the monastery, according to Metropolitan George of Nizhny Novgorod, “You can’t walk on tiptoes for long.” It’s so true. You can hold for a while, to create a good impression about yourself, but the monastery is a place where, on the contrary, you have to get rid of the masks, you have to quickly remove them from yourself, to see yourself as you really are; having seen yourself, to understand what you need to work on, what to repent of, what to rid yourself of, what to purify, and how to move towards Christ. For some it happens earlier, for others later, but in general, your inner essence (often hidden even from yourself) quite quickly begins to manifest itself.

—That is, on the one hand, you have an established person coming to the monastery, a fully mature person, sometimes even having some kind of position in society, and on the other hand, it turns out that, living in the world, he never learned anything about himself?

—That’s what happens most of the time.

—But there is such an opportunity in the monastery?

—Yes, if he properly understands what is happening with him. But quite often, people start to become despondent—they’re not used to seeing themselves as bad; they want to see themselves as good. It’s the flip side of pride. To stand before the Lord as you truly are, to finally embark on the true path, it’s important to see yourself correctly. It’s not for nothing that they say that the one who sees his sins is higher than he who sees angels. The monastery provides you with this opportunity. You have to humble yourself before the Lord, before others, and start from scratch, as it were: to begin to make an effort to deliver yourself from the old man, who sits very deeply within us.

—It would be useful not just for monastics…

—It’s good for everyone; it’s just that monastery conditions detect and reveal this quality faster. It therefore happens, by the way, that people come and they’re perplexed: We thought saints live here, but we found… No, the same kind of people live in the monastery, with the same human nature. Your nature doesn’t change because you believe in God—you only find support, and now you know that, relying on Christ, you can overcome this evil nature within yourself by the power of the grace of God. But it doesn’t mean that you were instantly transfigured and became different. On the contrary, the mental ailments that were veiled can escalate. After all, sometimes doctors aggravate an illness in order to identify it. It’s the same here. Therefore, someone who has embarked upon the path of salvation, not only a monk, but anybody has to understand that this will happen, first of all, by perception of his own sinfulness. As St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov) writes: When you truly see yourself perishing, then you will truly need the One Who will save you. Then your prayer to Christ becomes more powerful and your faith more alive.

—And you can also try to see yourself by going to a monastery on pilgrimage, joining in the spiritual life there?

—Of course. And what’s more: The longer a pilgrim stays at a monastery, the more difficult it becomes to return to the world. But all the same, when he’s just a pilgrim, the Lord sends him great consolation so he would return to the world full of strength. But for a monk, a monastery is not a place of relaxation—it is his battlefield. Therefore, the monk perceives this life differently. He may be oblivious to the beauty around him, because he is immersed in himself, in a battle in which he usually sees himself defeated for the time being. It’s good for us proud modern people to see ourselves defeated. It’s not for nothing that Elder Silouan said that the Lord allows the proud to suffer from their weaknesses…

—But then, modern man isn’t just weak physically. When he sees his weakness, he often falls into despair, which he has no strength to get out of.

—Here it’s very important to trust God. If you don’t trust God, but trust more in your own strength, it will be truly difficult for you to get out. You just have to believe that the Lord will pull you out at any moment, as the apostle Peter who had begun to doubt and then sink. Not everyone endures the test of faith. I know, for example, people who received monasticism in the 90s and were really zealous at first, then time passed, and they gave up everything and left for the world. Perhaps it happened because they were seeking self-expression above all, even in faith. They didn’t seek God as daily bread, not salvation, but some kind of self-satisfaction. But, having become Christians, and especially coming to a monastery, we in fact enter a sphere where there is not only the Lord—there are also dark forces that begin to play on our weaknesses. We enter into a serious struggle, even if we ourselves don’t fully understand it. And here, in my opinion, the man who has a simpler and humbler soul always wins—not an intellectual, not a strongman with an iron will, but a simple, humble man. Therefore, our goal is to become as simple as possible before God and as humble as possible before men.

—Mother, what things would you advise to pay attention to for someone who is thinking about monasticism and choosing a monastery?

—I can speak about the experience of our monastery. The sisters whom we receive in the monastery, as a rule, first come here just to work for quite a while, to live, and then stay for a long time. At some point they felt that there was no longer any sense in returning to the world; they internally felt this was the place for them. We’re all on display, as we are, with our shortcomings, our weakness; we hide nothing. If someone lives in the monastery for a long time and goes to the obediences with the sisters, they know everything about everyone. And if a sister decides to stay, understanding that it’s not holy people living here, but normal people who are in a state of internal strife, realizing her own infirmities, and that she’s ready to go together with them towards salvation—and if I, the abbess, see that it’s possible to try her further on this path—then she stays with us as a novice.

It’s very easy to be charmed by our place, but this charm can play a cruel trick on someone. A monastery is not just a place; a monastery is first of all a monastic brotherhood or sisterhood.

—You said that people come to you in adulthood. But adults in our time, as a rule, have health problems. Can that be an obstacle to entering the monastery?

—It depends on the problems. Mental illness can be a serious obstacle, because monasticism is a path that requires a sober head. An unhealthy person simply won’t be able to assess everything correctly. They can come to stay, to labor for a while… People like that do come here, and they want to stay, but they don’t understand that monasticism is a very difficult path.

—And if the monastery doesn’t suit someone…

—I tell them right away. If I see that someone’s desire is not consistent with their understanding of the monastic life, with their capabilities, I tell them about it. But it’s possible I won’t see some problems immediately, and then it takes time.

—How long does it take now to get to the tonsure?

—I came to this monastery in 2007, and the first riassophore tonsure under me happened just this year. That is, twelve years passed. But, first, I came from another monastery. The way of life of our monasteries differ from one another. To begin with, I first had to properly understand myself in this place. And the sisters had to readjust. We all needed time. Some of the sisters, unfortunately, have left the monastery, and others have come. During this Great Lent we performed some riassophore tonsures over sisters who came in my time.

—Mother, what have you changed in the monastery?

—I haven’t changed much. Liturgy wasn’t served every day before me—it wasn’t possible then, but I came from a monastery where the experience of daily Liturgy originally existed, and I felt the difference very strongly. Liturgy is a great work, even if there are few of us and not all the sisters have the chance to go to Liturgy. When this Sacrament is celebrated, it affects the entire monastery. I would even say it affects the surrounding villages, and people start coming more. Here’s one example: On the feast of the Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God, we traditionally have a procession from the monastery through the village of Kostomarovo to the Don River, where there is a spring in honor of the Tikhvin Icon, and we serve a moleben there. As we were going through the village, I noticed that the people who a year or two ago just came out and stood by the road, watching us, were now joining the procession, walking towards the spring. That is, the liturgical life of the monastery is important for local residents too. And it’s very important for the inner life of the monastery.

I came from St. Alexei-Akatov Monastery in Voronezh, which was revived in 1990. At first, there were services there every day; sisters came who already had experience in the monastic life, albeit in the world. There were still old nuns there who had gone through the soviet period, being deeply faithful people. They didn’t have the practice of the monastery life, but they had the experience of prayer and the experience of standing in the faith. It’s also important that there was a men’s monastery there since 1620, and New Martyrs of Russia, the Hieromartyr Peter and others labored there. Of course, Kostomarovo is a great and holy place, but the monastery as such was not here for a long time, although, obviously, ascetics were laboring in the caves. We’re basically all starting over again.

When they appointed me abbess, I naturally came with some experience of pastoral care and tried to speak with the sisters as I was used to, as I had been spoken to. My confessors were distinguished by extraordinary love and mercy. Mother Barbara (Sazhneva) (the abbess of St. Alexei-Akatov Monastery—Ed.) is a very direct person, very honest, but merciful and kind, and very sincere. Having her before me as an example, I can’t even do otherwise—to the best of my abilities and according to the peculiarities of my character. I understand that my human weaknesses greatly hinder me. But you can’t hide from yourself; you have to work on yourself. The abbess is in a rather difficult situation. She has to guide the sisters and work on herself; and if I want the sisters to improve, I know that I also have to improve myself. It often happens that you consider yourself not entitled to say something, but it’s necessary to say it… But on the other hand, this position is very humbling. If someone thinks the abbacy is a place to show power, he is mistaken: It’s a place of extreme humility, if you really want everything to be God’s way.

—You came from the soviet era. Were your family believers?

—I’ll say this: There were no atheists in my family. I’m a second-generation city dweller; my parents were born in the countryside and moved to the city at a young age. Therefore, all of my grandmothers were believers, although they didn’t have the opportunity to go to church as often as we do today. It was difficult to be a Church person at that time, but I never heard any godless words in my family. On the contrary, I even saw the fear of God from my mother. I remember, they taught us in kindergarten that there is no God, and so on, and then one time we went to see my grandmother, and she had an icon hanging. They sat me under this icon, and I said something that I had been taught… I remember my mother was sincerely frightened when she heard these words. And when I saw her fear, that the Lord could truly punish me, I got quiet, and I felt embarrassed. I truly came to faith in my student years.

—How did you know you wanted to go to a monastery?

—Everything was gradual. I started going to church, and there one hierodeacon started talking with me about monasticism by the relics of St. Mitrophan, but very delicately… Then the spiritual father of one monastery persistently began to call me. At first such things scared me, but then I began to think, and eventually I told everything to the priest I was going to for confession at that time. And he said, “You should go to the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra; there’s a confessor Fr. Kirill (Pavlov) there—he’s a holy man. He very carefully advises people about going to a monastery. It would be good if you consulted with him.” I decided to go with a friend during winter break—I was in my last year of school then. It was quite difficult to get to Fr. Kirill: After me, he didn’t receive anyone else, and left. He told me: “Go to a monastery, my dear. Go—you have a good monastery in Voronezh. Go…” With these words, all my doubts fell away, and I already felt the desire. I defended my thesis in June, and in August 1992, I went to the monastery. Then I also went to Zadonsk, to Archimandrite Nikon, now a metropolitan, and he immediately advised me to go to the Voronezh Monastery, repeating that I absolutely had to go to the monastery. This again confirmed my thought…

—And your parents? They weren’t against your monastic path?

—My mother died when I was twelve, and my father is a very wise man; of course, it was difficult for him, and for me too, because he was left alone—that was the main issue for me. But seeing my desire, in the end he said, “Well, go. The doors to the house are open; if it doesn’t turn out alright, you can always return.” And I left. I usually find it very difficult to get used to new groups. But when I arrived at the monastery, I didn’t even feel any transition, any process of adaptation. I immediately felt like it was my family. And the sister I went to see Fr. Kirill with—we went to the monastery on the same day. Now she’s a schemanun…

—What would you wish for people who aspire to monasticism today?

—I would like to wish that they simply give themselves over into the hands of God. As I said: Become as simple as possible before the face of God, trust in the Lord as much as possible, expect nothing from anyone, don’t think you’re going to meet holy people now, don’t think that if you go to a monastery then something special is going to happen… They have to understand that the monastic path will be full of joys, but it will also be full of its sorrows. If someone is ready to walk this path for the sake of Christ and for the sake of his salvation, with the desire to see first of all his own weaknesses, his shortcomings, and to give himself entirely in the hands of God, then I think it will work out for him. If he thinks that someone owes him something, and because the Lord said to love, people are now obliged to love him with all his sins (and by the world “love” is often meant permissiveness), and he will live as he wants, and nothing can be demanded from him… I call that spiritual blackmail.

—That is how consumer society educates people now, after all…

—Whatever society fosters, it’s an illusion. We must first of all understand that no one owes us anything. We are indebted before the Lord. The commandment of God isn’t addressed to someone else, but to you yourself, and you won’t answer for someone else. That is, we have to understand what’s most important. If someone who comes to a brotherhood or sisterhood doesn’t want to see himself as he truly is, to work on himself, then everything will be in vain, and sooner or later, everything will end tragically for such a person.