Here in Appalachia, there are many thousands of people whose lives move in and out of chaos. Less than a paycheck away from a cascade of debt-borne disasters, personal behaviors add even greater danger. There’s no room for messing up. As a priest in the area, the stories come through the doors of the Church looking for assistance. Frequently, there’s a need to explain. Someone pulls a wad of receipts and medical bills from a purse and tearfully begins to relate the dominoes that have pushed them into begging.

There is good infrastructure in this part of the world (it could be better). There are agencies and social workers, as well as many generous and helpful people. No one is alone in all of this. But the most fundamental infrastructure is that of family – and it is the family that is collapsing under the weight of joblessness and drugs. In many areas, the most common family arrangement is that of grandparents raising children – the middle generation have been lost in the rising tide of drug-deaths and crime.

Chaos is always the greatest danger to human existence. Our creativity and adaptability also mean that we have greater opportunity to get things wrong. Most of our chaotic episodes come as the result of unintended consequences. Social and economic decisions in one place undermine fundamental structures in another. Drive through the Rust Belt, or the swath of former coal-mining communities and you’ll see what I mean. A war would have caused less damage.

It strikes me as interesting that we imagine war to be an answer to chaos. In the 60’s, the government created the “War on Poverty,” while we continue fighting the “War on Drugs” in what is now becoming its sixth decade. Neither, of course, has made much of a dent in its stated goals. “War” is a modern image of a form of progress. The 20th century witnessed the “War to End All Wars” (World War I) which, arguably, has been the source of all the wars following in what is now best described as the “Hundred Years’ and Counting War.” In point of fact, war is chaos. Chaos itself is never the solution to chaos, short of annihilation. This is the notion behind the phrase, “bomb them into the Stone Age.”

The great image of chaos in the Scriptures is water, especially large bodies of water. My Archbishop recently commented that the Hebrews had the same attitude towards large bodies of water as your cat. The waters are death:

Save me, O God; for the waters are come in unto my soul.

I sink in deep mire, where there is no standing:

I am come into deep waters, where the floods overflow me.

I am weary of my crying: my throat is dried: mine eyes fail while I wait for my God.

And

Thy throne is established of old: thou art from everlasting.

The floods have lifted up, O LORD, the floods have lifted up their voice;

the floods lift up their waves.

The LORD on high is mightier than the noise of many waters,

yea, than the mighty waves of the sea.

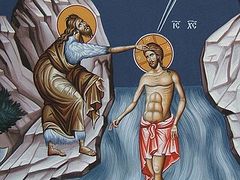

St. Paul echoes this imagery when he describes our Baptism as a “Baptism into the death” of Christ. I think that such imagery is largely lost on the average reader of the New Testament. Christ presents Himself to St. John the Baptist for Baptism. St. John hesitates. We assume that the issue revolves around Christ’s sinlessness. Why should He be baptized if He is without sin? St. John does not yet realize that these waters are those waters. Christ will later describe His ministry as “the sign of the Prophet Jonah.” Jonah was three days in the belly of the whale, and Christ is three days in the “belly” of the earth. But listen to Jonah’s description. His book relates a hymn sung from within that dark place:

“I called out to the LORD, out of my distress,

and he answered me;

out of the belly of Sheol I cried,

and you heard my voice.

For you cast me into the deep,

into the heart of the seas,

and the flood surrounded me;

all your waves and your billows passed over me.

Then I said, ‘I am driven away from your sight;

yet I shall again look upon your holy temple.’

The waters closed in over me to take my life;

the deep surrounded me;

weeds were wrapped about my head

at the roots of the mountains.

I went down to the land whose bars closed upon me forever;

yet you brought up my life from the pit,

O LORD my God.” (2:2-6)

This is a song, not from the belly of a whale, but from Sheol itself. This is a song from the chaos of death and hell. In His Baptism, Christ already enters (in a manner we cannot understand) the chaos from which He will bring us back. It is said that His submission to Baptism makes all Baptisms to be His. This is no longer the “Baptism of John.” This is something that Christ alone can give.

We cannot deliver the world from chaos through our own application of yet more chaos. Much of what modernity imagines itself to be building is not construction – it is destruction – a war on nature – of human nature above all.

“The thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy. I came that they may have life and have it abundantly. (John 10:10–11)

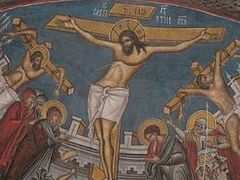

We do not heal, build, or make new through the instruments and chaos of war. Christ’s trampling down “death by death” is a paradoxical statement, in that His “death” is, in fact, eternal life. The same paradox is expressed in a Syriac description of Christ’s Baptism in which the Jordan River is said to have “burst into flames” as He entered it. When the Logos enters chaos, chaos never wins.

Modernity is a testament to the effectiveness of violence. It never changes hearts which are the seedbeds of all reality. The gospel of Jesus Christ rightly identifies chaos at its source and bravely goes into its yawning maw. It is there alone that death becomes life, order is re-forged, and the world emerges from the watery depths and becomes dry land once more.