“My mother took me alone to Liturgy on Holy Monday. It was a fine day, and I remember today, as though I saw it now, how the incense rose from the censer and softly floated upwards and, overhead in the cupola, mingled in rising waves with the sunlight that streamed in at the little window. I was stirred by the sight, and for the first time in my life I consciously received the seed of God’s word in my heart. A youth came out into the middle of the church carrying a big book, so large that at the time I fancied he could scarcely carry it. He laid it on the analogion, opened it, and began reading, and suddenly for the first time I understood something read in the church of God… And then the soft and sweet singing in the church: ‘Let my prayer arise,’ and again incense from the priest’s censer and the kneeling and the prayer.”1

Do these words touch our hearts, brothers and sisters? Perhaps, recalling our childhood, some of us can draw a similarly quiet, bright picture of the Church of God and Church prayers. Our great writer describes exactly what we saw and participated in today: the sun’s rays pouring through the narrow windows, the reader came out with a heavy book, and the wonderful hymn, “Let My Prayer Arise.” So touching and beautiful are these final days of waiting for the great joy of the Resurrection of Christ, so magnificently and reverently the Church honors the memory of the last earthly days of our Lord, and today, on Holy Tuesday, we mentally follow the Lord, conversing with His disciples. We are heading for the Holy City of Jerusalem, where terrible events will soon take place—the murder of the Benefactor of mankind; we are going to hear His final instructions.

In Jerusalem, the Lord goes to the Temple, and the spiritual leaders—the Pharisees and Sadducees, irreconcilable enemies in the fight for power over human souls—again address him with their insidious questions. They come to Him not together but in groups, first one, then the other. If they don’t manage to outdo Christ in debate, they think they will confuse Him with their multitude of questions. If they hadn’t previously managed to defeat the Lord by their cunning, then now they want to scare him with their numbers. Their anger and hatred, like a terrible leprosy, constantly inflames a clouded mind; like a leper claws at himself, his sores, trying to find at least some consolation from the pain of this excruciating itching, so they invent more and more questions to trap their Savior, to provoke Him to a reckless word and, seizing Him for it, to bring Him either to the courts of the secular power—the pagan Roman proconsuls, or to the spiritual courts—the Sanhedrin.

What joy and pleasure they expect to receive, seeing His sufferings and torments—truly satanic joy. But the Lord, knowing their guile, wisely answers the Pharisees that there is no sin in God’s chosen people giving to the Roman occupiers: Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's; and unto God the things that are God's. He answers the Sadducees, who did not believe in the resurrection of the dead, convicting them of deliberately concealing the words of Sacred Scripture, which they knew by heart: Have ye not read … what God spake unto him, saying, I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob? He is not the God of the dead, but the God of the living. After these answers, no one asks Christ any more cunning questions. They are accused of lies and deceit and shamefully leave.

Only His disciples and those listening remain with Christ, not asking any questions, but awaiting guidance. Addressing them, the Lord rebukes the leaders of Israel: Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees!—an expression of extreme sadness about the stiff-necked people. Christ does not need the appearance of righteousness, but righteousness itself; He does not need excessive pledges and podvigs, but mercy and faith. Having said this, He leaves the Temple, and the disciples come unto Him and show Him the magnificent Temple buildings: how powerful, large, and beautiful they are. Instead of praise, they hear that it will all be destroyed. Having ascended the Mount of Olives, the disciples alone, without any outsiders, ask about when the Temple will be destroyed, and the Lord speaks a terrible word about the signs of the approach of this time. Wars, famine, epidemics, earthquakes, false teachings, hatred, lawlessness abounding… And most importantly—love waxing cold.

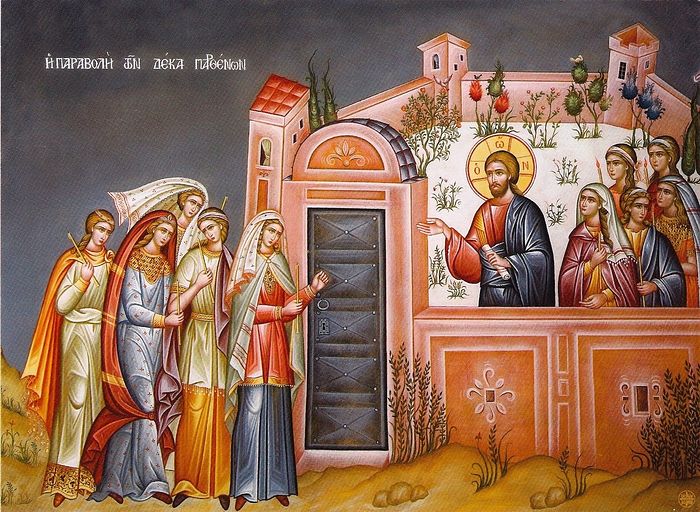

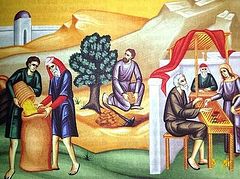

After this, Christ tells two well-known parables: of the ten virgins and of the talents. If we recall the contents of the sticheras that we sang at today’s service, we will see that they reflect neither the insidious questions of the Pharisees and Sadducees, nor the threatening omens of the end of the world, but reveal these two parables. Their common purpose is to induce towards vigilance and attention. And we hear the word of Christ: Watch! Very little time remains until the Wedding feast to which we are invited, and we must soon give an answer for our use of our talents. The virgins are you and I, that is, the Church; the sleep while awaiting the Bridegroom is death; the oil in the lamps is the virtues; and those who sell are all those who are in need of our help. The talents, spoken of in another parable, are our abilities, given us for our own good and the good of others. But how can we, who are truly fools because of our worldly cares and passions, and unfaithful slaves, acquire oil and multiply our talents?

It turns out there are common means of achieving these two goals: “Receive His gift with fear; make it gain interest for Him; distribute to the needy, and make the Lord thy friend” (Sticheron on “Lord, I have cried unto Thee...” at the Presanctified Liturgy). Mercy is the universal key that opens the door of the joyous Wedding feast to us and makes us good servants of God. What is mercy? It is the mother of love—the love that distinguishes a Christian, surpassing all signs and serving as the sign of the disciples of Christ. And who are the merciful? Are they those who distribute money to the poor and feed them? No, this alone does not make one merciful—it must be heartfelt mercy. And merciful are those who are impoverished out of love for Christ, Who was impoverished for our sake, but, remembering the poor, widows, orphans, and the sick, and having nothing to give them, suffer from pity for them and weep like Job, who says of himself: Did not I weep for him that was in trouble? (Job 30:25). When they have something, they help those in need with sincere kindness, and when they have nothing, they give them persuasive instructions about what contributes to the salvation of the soul, obeying the word of him who said: I received gratuitously, I give away liberally (Wisdom 7:13). Such are the truly merciful, who are blessed by the Lord Jesus Christ. By such mercy as on a ladder they ascend to perfect spiritual purity, says St. Symeon the New Theologian.

If yesterday was permeated with the memory of the Joseph’s resisting the temptation of Potiphar’s wife, then today, mercy is presented to us as a prerequisite for salvation. “For he who accomplishes a single virtue, even if it be the greatest, while overlooking the others—and in particular, almsgiving—will not enter with Christ into eternal rest,” we read in today’s Synaxarion. With this in mind, let us concentrate, brothers and sisters, on these days of the forefeast; let us be attentive and sober and cleanse our souls with repentance and Communion of the Holy Mysteries of Christ; let us clothe ourselves in a garment of light and spiritual joy; let us take the precious lamps of our souls, let us fill them with mercy and the other virtues and patiently, driving away sinful sleep and carnal enervation, let us await the call: Behold, the bridegroom cometh; go ye out to meet him.