Introduction by Matfey Shaheen:

In this article by Doctor of Historical Sciences Yurij V. Danilets, a professor of the Ukrainian history department at the National University of Uzhhorod, we delve into the history of the Carpatho-Rusyns from what is today Eastern Slovakia, who were persecuted for their faith, and even accused of being agents of Moscow—all because they simply wanted to build an Orthodox Church; and for that, they suffered under Austro-Hungarian Uniate persecution.

These Rusyns were part of and influenced by the mass conversion to Orthodoxy which occurred in America under St. Alexis Toth, sparked by the sheer hatred the Catholic authorities had for them. Many of them came to America as Uniates, and due to discrimination against them by the Catholic Church, ironically, converted to Orthodoxy and ended up bringing the faith of their fathers back to their fatherland—from America of all places! Yet when they returned to their native Carpathian villages and wanted to build Orthodox Churches, they were arrested and prosecuted by the catholic authorities, and thought of as traitors establishing a “Moscow colony” and spreading Orthodoxy, which was considered “Russian propaganda.”

In light of the tragic events in Ukraine, their story is particularly relevant, as we sadly see the very same arguments levied against members of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church by violent nationalist schismatics today. That is, that those who are members of the Orthodox Church, or support the canonical church are somehow agents of Moscow, that the Orthodox Church is secretly a conductor of Moscow’s influence, and that faithful born and raised in Western Ukraine worship a foreign, “Moscow god”1. In modern Transcarpathia, priests have even received death threats. We pray that people will be aware of their suffering, and through the prayers of all the Carpatho-Rusyn Saints, the Love of Christ will prevail in Transcarpathia and peace will come to Ukraine.

Throughout its millennia-old history, Transcarpathia has repeatedly been enslaved to more powerful neighboring states, which oppressed and limited the rights of the population of this land. Such was the policy of the Austro-Hungarian and Czechoslovakian central authorities, primarily in economic and religious matters. This topic is complex and multifaceted. There are many examples of the repressive policies of Budapest and Prague regarding the Rusyns. This article will focus on one of the episodes in a long series of dramatic events caused by the actions of the Hungarian (Austro-Hungarian) authorities in Transcarpathia. It will also discuss the oppression of the Rusyns of the village of Becherov of the Sáros County or Šariš Župa2 (as it is called in Slovak), which is now located in the Bardejov District of Slovakia, whose inhabitants decided to return to Orthodoxy in the beginning of the twentieth century. Moreover, we will turn not only to printed materials, but also to archival sources.

The history of the revival of the Orthodox Church in Northeastern Hungary (which Transcarpathia was a part of), was of interest to many researchers; many articles have been published on the revival of Orthodoxy here, on the Marmarosh-Sigot trials, on the policy of Magyarization3 of the local population. However, not all publications had an archival basis, not all were impartial, because their authors handled the situation based on church affiliation or political convictions. There is still no special monograph on the history of the revival of the Orthodox movement in Eastern Slovakia at the beginning of the 20th century.

In Austro-Hungary, laws were in force (in 1868 and 1895), according to which all citizens of the empire were free to change their religious affiliation. But in practice, as the experience of the first years of the twentieth century showed, these laws were applied selectively. We will not dwell here on the reasons for the Orthodox movement among the Ruthenians in Austro-Hungary, but we will name the main ones pushing the Rusyns to leave the Union of Uzhhorod:

In Austro-Hungary, laws were in force (in 1868 and 1895), according to which all citizens of the empire were free to change their religious affiliation. But in practice, as the experience of the first years of the twentieth century showed, these laws were applied selectively. We will not dwell here on the reasons for the Orthodox movement among the Ruthenians in Austro-Hungary, but we will name the main ones pushing the Rusyns to leave the Union of Uzhhorod:

-

The policy of denationalization and Magyarization of the local population, carried out by the Hungarian authorities and the Greek Catholic hierarchy, the aim of which was the complete assimilation of the Rusyns, and their transformation into the faithful sons of the Austro-Hungarian Empire;

-

economic pressure from the Greek Catholic clergy and local landowners;

-

and the struggle for the preservation of the Eastern rite and the opposition to the Latinization of the Church.

All these reasons, as well as many others derived from them, sparked the revival of Orthodoxy in Northeastern Hungary.

By the end of the nineteenth century, many Rusyns went abroad to earn money, primarily to the United States, to Canada, and Latin American countries. In a foreign land, many new parishes, brotherhoods, and shelters were founded. In 1889, the Greek Catholic Priest Alexis Toth from the lands of Prešov came into sharp conflict with the Roman Catholic Archbishop John Ireland, administrator of the diocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. The cause of the conflict was the desire of the American Catholic bishops to transfer spiritual leadership of the Greek Catholics from Austro-Hungary to the Polish Catholic priests. This was done in order to finally Catholicize (Latinize—i.e. to leave the Greek rite and follow the Roman rite), the Rusyns immigrants, and force the Uniate priests to return to the Old World. The Pittsburgh bishop even declared that “a married priest is not simply bad—they can’t even be Catholic.”4

Father Alexis Toth The consequence of this conflict was that Father Alexis Toth, after a meeting with the flock, sent the trustee John Mlinar to San Francisco, to the Russian Orthodox Bishop Vladimir (Sokolovsky). “We shall not eternally bow before foreign bishops, let’s find a Russian one at last!”5 A parishioner said at a meeting St. Alexis called. To the amazement of Mlinar, however, Bishop Vladimir did not allow him to receive Holy Communion, explaining that he was a Catholic, and not Orthodox. This fact shocked Mlinar, and he wrote Father Alexis Toth a letter, in which he asked the question: “What Faith do we really have? They taught us—and you taught us—that we are Orthodox, and yet here, an Orthodox Bishop did not allow me to go to Communion—he sent me away to a Catholic Bishop. What is our faith? They told me that I am a Uniate! What kind of Uniate? This is the first I’ve heard about this in my life, and I consider myself an Orthodox Christian!”6

Father Alexis Toth The consequence of this conflict was that Father Alexis Toth, after a meeting with the flock, sent the trustee John Mlinar to San Francisco, to the Russian Orthodox Bishop Vladimir (Sokolovsky). “We shall not eternally bow before foreign bishops, let’s find a Russian one at last!”5 A parishioner said at a meeting St. Alexis called. To the amazement of Mlinar, however, Bishop Vladimir did not allow him to receive Holy Communion, explaining that he was a Catholic, and not Orthodox. This fact shocked Mlinar, and he wrote Father Alexis Toth a letter, in which he asked the question: “What Faith do we really have? They taught us—and you taught us—that we are Orthodox, and yet here, an Orthodox Bishop did not allow me to go to Communion—he sent me away to a Catholic Bishop. What is our faith? They told me that I am a Uniate! What kind of Uniate? This is the first I’ve heard about this in my life, and I consider myself an Orthodox Christian!”6

In February of 1891, Father Alexis Toth himself went to San Francisco, and asked the bishop to receive him together with his flock into the heart of the Orthodox Church. On March 25, 1891, Bishop Vladimir served the Divine Liturgy in Minneapolis, which marked the beginning of the history of Orthodoxy among the emigrants from Austro-Hungary.7

The Greek Catholic Bishops: Yuliy Firtsak of Mukachevo8 and Ján Vályi of Prešov9 on February 12, 1893, sent a message to the US entitled “To our beloved sons living in America”.

They expressed regret that they could not provide spiritual support for their emigrants, and suggested that believers perform rites and receive sacraments with the Roman Catholic priests (where there were no Greek Catholic pastors). In addition, the bishops strictly admonished the flock to stay away from Father Alexis Toth.10

We have brought up these facts here, for the reason that already by the end of the nineteenth, and beginning of the twentieth centuries, a significant portion of the emigrants returned to their homeland, bringing back Orthodoxy (ironically, the faith of their fathers) with them. Of the three centers where the Orthodox movement began in the early twentieth century, two of them—the villages of Becherov (Bardejov District of Slovakia) and Velyki Luchky (Mukachevo district, Transcarpathian Ukraine)—were directly connected with the movement of mass conversion to Orthodoxy in the United States.

The Orthodox movement was heard about for the first time in the village of Becherov via reports from the American press. The newspaper “Svet” (Light), in the issue of April 8 (21), 1900, posted a letter from a resident of this village Vasyl Tutka. He said that a local priest, learning about the raising of funds in the United States for the construction of an Orthodox church, began to put pressure on local residents. The peasant quoted the priest: “Watch out! I’ll teach you to mess with the Moskal’11 faith! We’ll send soldiers to kick you out of the village and seize your land and homes!”12

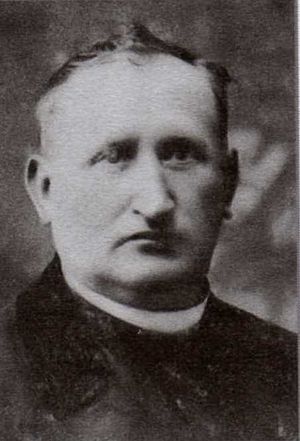

Priest Mikhail Artim On September 20, 1901, a letter came from Budapest from the Ministry of Cults and Public Education to Bishop Ján Vályi of Prešov. It stated: in connection with the fact that “a pan-Slavic trend with Orthodox overtones was uncovered in Becherov which spreads dissidence in the country,” it is necessary to investigate and establish: the number of people who converted to Orthodoxy in Becherov and its surrounding region, as well as what kind of coordination was noticed between persons planning to create an Orthodox community.13 Fulfilling the order of the ministry, the Bishop of Prešov ordered an investigation. Its representative, District Dean Ivan Kapishinsky and his assistants organized a general meeting of the villagers on October 17, 1901. Peasants were also invited to the meeting, who wanted to go convert, or had already converted to Orthodoxy (V. Tutko, V. Zbigley, P. Lazorik and others). Local priest Mikhail Artim said that the Orthodox movement in Becherov arose under the influence of emigrants from the United States. He said the desire to leave the Unia was only for financial reasons: supposedly the peasants, in the event of conversion to Orthodoxy, hoped for financial assistance from Russia. The priest brought the religious issue to the political plane. “If they convert to the Moscow faith and receive permission to build a church, then there will be a Moscow colony in Becherov as in there is in Minneapolis in America, and later the whole land will turn into Moskal’ territory.”14

Priest Mikhail Artim On September 20, 1901, a letter came from Budapest from the Ministry of Cults and Public Education to Bishop Ján Vályi of Prešov. It stated: in connection with the fact that “a pan-Slavic trend with Orthodox overtones was uncovered in Becherov which spreads dissidence in the country,” it is necessary to investigate and establish: the number of people who converted to Orthodoxy in Becherov and its surrounding region, as well as what kind of coordination was noticed between persons planning to create an Orthodox community.13 Fulfilling the order of the ministry, the Bishop of Prešov ordered an investigation. Its representative, District Dean Ivan Kapishinsky and his assistants organized a general meeting of the villagers on October 17, 1901. Peasants were also invited to the meeting, who wanted to go convert, or had already converted to Orthodoxy (V. Tutko, V. Zbigley, P. Lazorik and others). Local priest Mikhail Artim said that the Orthodox movement in Becherov arose under the influence of emigrants from the United States. He said the desire to leave the Unia was only for financial reasons: supposedly the peasants, in the event of conversion to Orthodoxy, hoped for financial assistance from Russia. The priest brought the religious issue to the political plane. “If they convert to the Moscow faith and receive permission to build a church, then there will be a Moscow colony in Becherov as in there is in Minneapolis in America, and later the whole land will turn into Moskal’ territory.”14

Peasants who were convicted of converting to Orthodoxy rejected these allegations. They stated that the reason for their conversion to the Orthodox faith was an acute conflict between their relatives and a local priest that arose more than three years ago. “Our women15 and fathers wrote letters to us when we were in America, in these letters they complained about the pastor.”16 Therefore, the emigrants, upon returning home, decided to build a separate church and transfer it to the jurisdiction of the Orthodox bishop in Budapest.17

In March of 1901, I. Banitsky and V. Tutko visited the Orthodox bishop, who gave them instructions on the legal transition to the Orthodox Church. However, when they returned home, the police searched them, confiscated their books, and arrested the owners themselves as “traitors to the Empire.”18

The protocol of the investigation of September 17 and the documents of November 11, 1901 show that the accusers did not recognize their membership in the Orthodox Church. The documents of the episcopal inspection were sent to state bodies, which gave their “proper” assessment. The prosecutor Janosh Paxi ordered the arrest of three peasants: A. Zbigley, V. Zbigley and V. Tutka, for anti-Catholic propaganda. The peasants’ homes were searched and periodicals from the USA were seized.19 On March 19, 1902, they were charged.20 However, after some time, the prosecutors failed to prove any guilt, and they were released.

We learn about the further development of the Orthodox movement from a letter marked “Secret” sent by the Ministry of Cults and Public Education on May 14, 1903 to Bishop Ján Vályi of Prešov. The ministerial official noted that at the end of December 1902 a message was received from a Becherov priest in Budapest, in which the latter said: “Military-aged men who were in America, absorb schismatic teachings and Pan-Slavism, and returning to their homeland, disseminate them, and also collect funds for Russian organizations in America.”21

From the investigation, it became known that Fedor Hryvna, a native of Becherov, was engaged in fundraising in the United States. He also allocated a plot of land for the construction of the future Orthodox church in his native village. “It follows from the report of the chief judge,” the letter states, “that F. Hryvna and several of his associates were in bad relations with their priest, and this also led to the spread of Russian propaganda.”22

Further, the author of the letter reported that the Minister of the Interior Kálmán Széll drew attention to a publication in the newspaper the “American Orthodox Herald”, published in New York, which posted messages on the decision of the Saint Petersburg Synod to support the Orthodox faith in America, and those persons who intend to return to their homeland and contribute to the construction of an Orthodox church in the village of Becherov. The ending of the aforementioned letter is extremely important. In particular, the official writes in it: “Noting that the majority of emigrants will return home, and if an Orthodox church will be built in Becherov, then later in other cities, especially in the east of our country, Orthodox churches will also be built. This is fraught with a threat not only religious, but also national-political. From the above it follows that the construction of an Orthodox church in the village of Becherov should be prevented by all legal methods, since Russian political pan-Slavism is leaking into the country on the pretext of a religious institution.”23

The bishop was encouraged to take measures to identify the initiators of the spread of “political pan-Slavism” in Becherov for its further eradication.

In early August 1903, a group of peasants from Becherov visited the Orthodox bishop in Budapest. The Bishop supported the idea of building an Orthodox church. The peasants, in the case of the establishment of the Orthodox community, were attached to the parish in Eger. In a letter dated August 29, 1903, they asked the bishop to send one of the most respected priests to Becherov for the peaceful settlement of affairs.24

Having studied all the necessary questions, the Bishop entrusted this task to the canon Cornelius Kowalicki, who held a “hearing” on September 10, 1903 in the village. During the investigation, the peasants admitted that they visited Orthodox churches in the United States, that they raised funds for the construction of a church in their homeland, and visited the Orthodox bishop in Budapest. They said that they wanted to go to Orthodoxy because of the local catholic priest Mikhail Artim: “Especially since he became a state deputy in parliament (1901-1905), on Sunday and holidays he is not at home, but if he accidentally is at home, he is engaged in private affairs of foreign people; sometimes it happens that on Sunday and holidays he preaches, but his sermon is not connected with faith and moral behavior, but is connected with state affairs and private events.”25

A result to all these events in Becherov is summarized in article 164 of 1904 newspaper Tserkovnye Vedomosti (Church News): “The suppression of Orthodoxy in the village of Becherov was accompanied by numerous arrests and processes aimed at accusing members of the movement of treason and pan-Slavic propaganda, but a most thorough investigation in this case did not reveal the slightest trace of treason or pan-Slavism.”

Sources that would testify to the further development of the Orthodox movement in the village of Becherov in the Austro-Hungarian period were not found. It is only known that several peasants who were persecuted by Austro-Hungarian soldiers returned again to the United States. Subsequently, when these lands became part of Czechoslovakia, a significant part of the village converted to Orthodoxy.