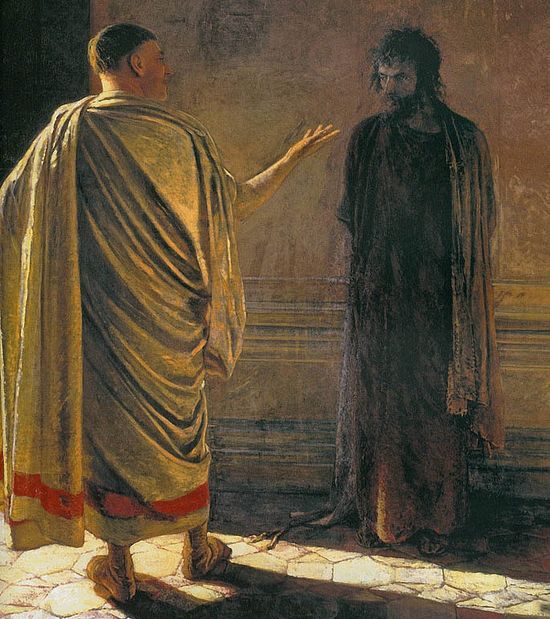

Nikolai Ge. What is truth? Christ and Pilate,1890. Photo: wikipedia

Nikolai Ge. What is truth? Christ and Pilate,1890. Photo: wikipedia

Some ten or so years ago, my wife and I were hunting for a long-ish audiobook to entertain us as we made a 10-hour drive. A novel was one possibility, but none came to mind. As it was, we chose a book named “Salt.” It was an account of the world in terms of salt – its use, its production, its vital importance to human life, and its place in the shaping of our history. I was skeptical as the trip began, but found myself intrigued as the hours rolled by and we journeyed across world history courtesy of everyone’s favorite condiment. Salt apparently belongs to something of a literary genre. The author of Salt has also given us Milk, Cod, Salmon, and Paper. I need to schedule more road trips.

What these fascinating books illustrate is that the story of the world, and civilization, can be told from any number of angles. Is the world really just the story of salt? Or, could the story of the world be told from the point-of-view of a single grain of sand? Doubtless, more would be said of the endless procession of ocean waves than is accounted for in our historical travails. As narrative creatures, we tend to dismiss the grain of sand as nothing more than background, a prop that supports the real action. A single grain’s story, however, would provide a great deal to consider. The silica and other elements that make up the average beach have an origin, no less complex than our own, though with fewer words and emotional tensions.

These exercises in historical perspectives are instructive for understanding the limits of all historical conversations. In history, we are always right to ask, “Who is telling the story? What’s this story about? From what point of view is it written?” If we were speaking of a “pure” history, then it would be the story of everything, about everything, told from everything’s point of view. Such, of course, is impossible. Choices must be made. When the choices are made, those questions will be answered more finitely and with greater precision. But what is then called “history” is not really about everything – but about a few things, and always with a point.

During a time of social upheaval, one of the most disturbing aspects of our lives is the turmoil within the public narrative. How do we speak about ourselves and others? How do we describe what is taking place. What is unfolding?

For the faithful, this disturbance should be revealing. The nature of the secular world is that it establishes the dominant narrative for the world. Without noticing, we quietly make the Christian story to be a sub-plot of this larger account. Our faith becomes what secularism tells us: a personal option that is, at most, a religious life-style. We feel powerless and worry that the voice of the Church is silent. Indeed, I hear this when various people suggest how the Church could make its voice more “effective.”

There is a “clash of narratives” as Christ stands before Pontius Pilate. Pilate imagines that the Roman Imperium is the true narrative and defining story of the world. He threatens Christ, “Don’t you know I have the power to kill you or to release you?” For Christ, the Roman Imperium is but a passing moment within the salvific providence of God. “You would have no power over me were it not given to you from above.”

This same clash of narratives occurs day-by-day in our own lives, though we rarely notice. We hear the dominant cultural narrative announce its importance and power. Our response is anxiety and concern flows from the fact that we believe its claims to be true. Imagine Pontius Pilate’s shock at being told that he would have “no power” over Jesus had it not been given to him by God (“from above”). It is Christ’s complete dismissal of the Roman narrative. The martyrs of the early Church lived in the same dismissal. Their faith was the full acceptance of the narrative we have received from God in Christ. Christ’s death and resurrection is the final word of God on the outcome of human history. In Christ, history comes to an end, and we won. That quiet assurance eventually led to the complete failure of Rome’s claims.

The danger resurfaces, however, as converted empires, and their secularized children, begin to assert new narratives that seek to replace the gospel of the Kingdom of God with the bastardized gospel of progress and human perfection.

There is always a danger within the political life of modernity that our participation will mark our capitulation to its narrative. As such, our vote (or other such actions) always borders dangerously on the pinch of incense offered to the emperor as worship, a thing rejected as idolatry by the early martyrs. I say, “borders,” because it need not be a capitulation. But, in order to refrain from that capitulation and blasphemous offering, there is a need to deconstruct our own vote.

So, what is the narrative that explains our vote? Do we imagine that history depends on such a thing, that the world is being constructed through politics? Again, in His dialog with Pilate, Christ said:

“If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would have been fighting, that I might not be delivered over to the Jews. But my kingdom is not from the world.” (John 18:36)

The ballot is certainly a “peaceful” way of joining battle (thank God!), but it, nevertheless, generally assumes the Hobbesian contract in which the world is a pitched battle for control. The nature of the American social contract is an agreement to allow the ballot box to replace the battlefield. Nevertheless, it presumes the supremacy of the ballot. That is its presumed narrative.

For the Christian, the narrative of the gospel of Christ is, always, the controlling structure of our life. That work of Christ, completed in His death and resurrection, are the sole source of peace and true meaning. We may vote, but the outcome rests in Christ, just as surely as the outcome of Pilate’s judgment was not truly in his own hands. None of this denies the actual historical reality of our actions. Rather, it affirms the historical reality of Christ’s actions and their lordship over every human reality. There may be an election whose outcome could be classified as “death.” It remains a fact that Christ “tramples down death by death.”

For too many, the Cross of Christ has disappeared into the historical past and become a “fact” about which we proclaim a doctrine, a religious belief. As for the present, we take up our swords (even the peaceful ones) and imagine ourselves as having been delivered into the wars of this world for good or ill. (Do your best!) However, the historical character of the Cross does not exhaust its content. The Cross is an event of the God/Man. It is the marriage of heaven and earth, both within time and utterly transcendent of time. It is an eternal moment while being truly historical. Its “cause-and-effect” is equally eternal and triumphant over every human cause. Every human cause is thus “judged” by the Cross. An election, like every act of the human will, stands before the Cross and has its meaning within the light of the Cross. It is only in that Light that we see light.

Christ’s words, “Be of good cheer. I have overcome the world,” remain true and triumphant. Today, this is the story by which we live. All of creation holds meaning only in its light. God forbid that we imagine this to be a religious conversation and not a conversation about the whole of life.

We all stand before Pilate. However, it is God’s story that rules the world.