Alexander Alexandrovich Lavdansky is a renowned modern Russian iconographer. A successful avant-garde artist whose paintings were actively sold and exhibited at 28 Malaya Gruzinskaya Street (Moscow), in the late 1970s he gave up secular painting and started studying iconography. And after surviving a fall from scaffolding, he decided to get baptized…

In his interview with Pravoslavie.ru, Alexander talks about his creative path of icon painting, what modern iconoclasm is, and explains how icons are always about the present.

Alexander Alexandrovich Lavdansky

Alexander Alexandrovich Lavdansky

“The aim of the dominant contemporary ideology is to destroy the image of God in man”

—Alexander Alexandrovich, is it true that your creative search in the sphere of secular painting eventually brought you to icons?

—You are basically right. In my work of the 1970s I didn’t really comply with the requirements of official art, but rather by late Gothic art and Northern Renaissance—that is, mainly Christian art. As I see it now, for me that was better than beginning with, say, Abstractionism or even Postmodernism. I remember that the theme of the apocalypse in art interested me most. The world was already changing dramatically, and the reference points I saw at the end of history led me to its beginning—to Christ. The knowledge of God’s appearance to people and His sacrifice for mankind filled all that was going on, and still goes on, with deep meaning.

—You related how, when you were on your faith journey and still unbaptized, you fell from scaffolding while working in a church with a team of restorers. After falling about sixteen feet down, you miraculously caught hold of the uncollapsed section of the scaffolding and survived. After that you were baptized. But what went on between that point and your conscious life in the Church?

—As for my creative work, I was immersed in iconography, studying it thoroughly. I continued to create some secular paintings too, but calmly, without “creative hysteria.” Peace came after the mentioned fall.

Everything was typical in my church life and I couldn’t avoid being a neophyte. I even wanted to live at a monastery, although I was married. I am indebted to my late spiritual father, who strictly forbade me to do so: “Everyone should serve God according to his calling.” In that period I walked away from secular painting—not because I was a religious neophyte but because I had lost interest in it. The realm of iconography was more “expressive” and meaningful to me. I like the theme of the veneration of icons. It involves both the creation and veneration of icons—the latter is sometimes confused with the concept of worship—it’s a conscious position of iconoclasts. In eighth-century Byzantium, iconoclasm was apparent to the naked eye; it still exists today, but, I would say, in deeper forms. Modern iconoclasts are not only trying to destroy icons, calling their veneration “idol-worship”, as before. Today the aim of dominant ideology is to destroy the image of man, the image of God in man… That is iconoclasm of the worst kind.

And we can oppose this by the veneration of icons and traditional art.

—Art in the broader sense, not only iconography?

—Yes. I have a friend who is a professor in the Sorbonne. He recounted how some fifteen years ago he dropped in at the French Academy of Fine Arts. The students there were studying, making plaster casts, painting still lifes and models. He was there again two years later and was terrified. There was emptiness; nobody cared about the image of the world created by God and of man created by God anymore. It was another example of modern iconoclasm.

“Above all, I care about tradition”

Alexander Lavdansky. Photo by Sasha Manovtseva —When it comes to icons (I mean, church art in general: painting icons, monumental frescos, mosaics), do believers who come to church understand the language of icons, theological nuances and so on? Or they don’t really need this: they have grasped the subject and that’s enough?

Alexander Lavdansky. Photo by Sasha Manovtseva —When it comes to icons (I mean, church art in general: painting icons, monumental frescos, mosaics), do believers who come to church understand the language of icons, theological nuances and so on? Or they don’t really need this: they have grasped the subject and that’s enough?

—Of course, the ability to “read” icons helps us understand many doctrinal elements better because icons are works of art, a type of philosophical thought and preaching at the same time. So we need to explain and show this to the faithful—I think it is a task of every parish.

Now we are painting frescos in the Church of St. Alexander Nevsky in Volgograd.1 This city was almost wiped off the face of the earth several times, and its restoration began after the Second World War. Recently they have lovingly reconstructed this church (originally built under Emperor Alexander III) in the Neo-Byzantine style.

Now they are working on the beautification of the church precincts, and splinters of shells, cartridges and human remains have been found. Some prayer beads have been discovered among human remains lately… And we are beginning to feel what we are doing more keenly, the importance of the appearance of a church and frescos in this place…

And now experts hope that we will do well and are ready to make guided tours around the church, explaining the frescos’ subjects and iconography to guests.

If you want people to linger and peer at frescos and study their iconography, they shouldn’t arouse people’s aversion. If a painter works indifferently or thinks of something else during his work, he is sure to have poor results.

—When you are going to paint frescos for a church, how do you plan this program?

—Above all I care about tradition. We must not only love our neighbors who are near us but also those who lived before us and created this iconographic tradition.

It is important to understand what they meant. At the same time, it is important to look at the architecture of every particular church and so on. Take St. Alexander Nevsky’s Church, which was built in the Neo-Byzantine style in the nineteenth century and demolished in 1932. Its architectural style must have influenced its interior. But back then knowledge of Byzantine and Old Russian art was poorer than in our days. There was St. Petersburg Imperial Academy of Fine Arts with its Department of Church History, but ancient icons and frescoes weren’t fully discovered and restored. So they painted frescos in churches in the Academic style according to the dictates of time. Today, when it is possible to familiarize ourselves with genuine Byzantine art, we paint frescos in churches as their walls require, taking into account the way modern people understand this.

We could talk about styles for hours, but regardless of the style we paint or try to upgrade our skills in, what matters is that we never adapt to someone’s tastes, though we do listen to our customers’ opinions.

—If a church has already been covered with frescos in the Academic style and you need to paint icons for its iconostasis, is this diversity of styles permissible here?

—I have always tried to avoid this, but I didn’t worry when I couldn’t because it is also interesting in some aspects. One of my favorite monuments is Agios Ioanis Lampadistis Monastery in Cyprus. Its frescos are from the twelfth to the seventeenth centuries, and it is very beautiful despite various styles—one and the same place remarkably combines the wealth of styles of church art.

—Recurring to your journey of faith after Baptism: did you go through a period of coolness towards the Church?

—I did. And I am indebted to my spiritual father and my wife for going through it without serious losses. By her patience my wife literally dragged me out of this state of doubts regarding the importance of life in the Church. I didn’t want to go to church and didn’t know why it was necessary to attend services. She continued to go to services every Sunday without imposing anything on me and I was left with no option but to follow her. At that period I continued to paint icons and I think I did it poorly.

—You mentioned elsewhere that you learned icon painting by reading books by and listening to lectures of Olga Sigismundovna Popova [1938—2020; a famous Russian expert in Old Russian and Byzantine art.—Trans.]. What does studying by books mean? What was the main thing you understood about icons from Popova’s works?

—The way she selected materials was important to me. She saw Byzantine icons in the way only someone with a gift from God can see. Thus she enabled many others to see them in this light. Olga Sigismundovna didn’t teach any technique, but she spoke about the things that matter most. For example, she would dwell on light in Byzantine icons—the light which is the gleam of the uncreated light of Tabor—and how Byzantine masters conveyed it. This served as a guide in my path of icon painting.

Thanks to Olga Sigismundovna I understood that everything matters in icons. When I was a beginner, Palekh methods were widespread when you paint in a strict order: first mountains and architecture, then attire, and, lastly, the faces and flesh. First dark underpaint, and then proceed to bright colors. From her books I found that it was wrong, that you may start with whatever you like and that the most important thing is the wholeness of a finished icon. And the background on icons (which was almost destroyed by Palekh) is no less important than everything else. Sometimes, if you are painting an icon and your background isn’t golden, the background takes half the total time allotted for your work.

“I too painted poor icons; there is much to repent for”

At work —Many times I heard from iconographers that in the Soviet era their situation was very different from what they have today. Do you agree?

At work —Many times I heard from iconographers that in the Soviet era their situation was very different from what they have today. Do you agree?

—Yes, it was somewhat different in the 1970s and 1980s. Whenever someone decided to create icons and frescos in churches, it was clear that he was doing it because it was his vocation. For example, by the time I gave up secular painting I could make good money with it. And at that time you couldn’t earn much if you painted icons, and even painters found themselves in some cultural underground.

Today, there are many churches, new ones are being built, and church painters are able to make money (and that is good). However, many very specific individuals (who have little to do with icon painting) have appeared and they don’t care if they are going to paint on Church-related or secular subjects as long as they are paid for this work. It is very sad that such things happen, but I wouldn’t say that it is critical.

The Apostle Paul said: Notwithstanding, every way, whether in pretence, or in truth, Christ is preached; and I therein do rejoice, yea, and will rejoice (Phil. 1:18). We should be lenient towards them. If icons you paint aren’t very good, it’s still good. Above all, it isn’t good for the painter himself. But Christ is preached even in this way.

And someone always has an opportunity to turn to Christ, perhaps even through awareness of the fact that he used to paint icons without thinking what he did and without realizing his responsibility. I am no better in the sense that I too painted poor icons and have what to repent of.

“Icons are always modern, since Christ is the same yesterday, today and forever”

—Today some say: “Artists are looking back to Byzantium. It’s enough to try the patience of a saint!” What do you think of such statements?

—Such remarks seem strange to me. The reference point for our Church life and culture is Byzantium, and it was there that the most adequate language for visual representation of Christ and “things above” was found. Actually, the core of this language doesn’t change, but new works of art that match their age are created on the basis of it. Icons are always modern, since Christ is the same yesterday, today and forever (cf. Heb. 13:8). St. Andrei Rublev too painted using the language that had been found in Byzantium but was in keeping with his age; as a result he created great masterpieces. If he had embarked on his artistic search in the hope of “breaking with Byzantium” (clearly, this sounds absurd for that era, so I am saying this hypothetically), then there would have been no Rublev.

Now that some actively and deliberately strive to have “non-Byzantium”, no good comes of it.

—Which particular epoch inspired you on the journey in search of your art style?

—It depends. First old Russian icons, and then (after reading Popova’s books)—Byzantium itself. First the Palaiologos Dynasty, then I looked deeper—into the Macedonian period and the Komnenos Dynasty. Now I would describe my style as close to post-Byzantine art and Theophanes of Crete’s work. But what we are doing isn’t renovation: we are just trying to create modern icons while listening to tradition, so as a result we have some Middle Byzantine—Moscow style.

The sole purpose of this search for styles is to tell people standing in church about Christ, using art as an instrument.

—What can you say about icon painting in modern Russia in general?

—We, or, to be more precise, our descendants, will be able to see a general picture around 100 years later, while it is not very clear to us from inside. Yes, many things are inspiring. Some projects, such as, “After Icons”, appall me.

Recently, before my very eyes, Alexei Vronsky in Volgograd painted, “The Resurrection of Christ. The Harrowing of Hell.” This work has turned out awesome! He took Dionisius’ iconography and the traditional iconography of this subject and the result is with a deep meaning, concise content, and a theological and artistic sense.

—What do you feel about the fact that modern church art is not uniform, with numerous groups of artists who disagree with each other?

—It’s quite a normal phenomenon. Different opinions aren’t a bad thing; this has always existed and is normal development. The main thing is that one shouldn’t put his personal opinion above the Church and the Holy Fathers’ experience.

—If you need to paint an icon of a saint you know little about or whose iconography hasn’t fully developed yet (which is often the case with the New Martyrs), how do you arrange your work?

—First of all I read his Life, I study whatever I can find about him: reminiscences, letters etc; photographs of many new martyrs have survived, so I scrutinize them. I try to comprehend all of this in order to run my knowledge (including visual one) of this saint through the traditional language of icons. After all, human beings (though they are saints) of this world gaze at us from photographs, whereas on icons they are already with the Lord in Paradise…

In about 1978, at the very beginning of my journey, I met Archimandrite Gennady [the future Schema-Archimandrite Gregory (Davydov; 1911—1987), a great elder of Belgorod and the spiritual father of Elder Seraphim (Tyapochkin).—Trans.] and told him that I tried to paint icons. He answered me: “If someone—for instance, your customer, tells you that the saint on your icon is dissimilar to the prototype, don’t worry. Always keep in mind that the saint should be like Adam and there shouldn’t be falsity in his face and his figure. If they argue that your saint’s image bears no resemblance to the prototype, reply that he is in Paradise and we should look at him from this perspective!”

—Who else helped you on your way to icons?

—My spiritual father. Though he had little to do with art and never went deep into any details of icon painting, he always supported me. Whenever I faced any difficulties or couldn’t understand something, he would say: “Pray, I will pray for you too, and the Lord will enlighten us.” Every time the power of his faith cleared my mind instantly, as if I had received expert advice. I sensed his prayer even physically.

—Did the authorities hinder you from painting frescos for churches back in the 1970s and 1980s?

—In the 1980s we worked in Ukraine, and local financial entities flatly refused to give us permission to paint frescos in churches. They just prohibited this without explaining anything. But we painted them all the same, and whenever supervisors came to us we hid in the bushes. The priest would welcome a supervisor, give him something to eat and drink—and the situation would get quieter and we could finish our work.

“For me the Church is life”

—If we compare contemporary Church life with that of the Soviet era, what do you think is lacking now and what makes you happy?

—In the USSR the situation was very different: whenever you went to church, there was hardly room to turn around in it because there were very few churches. And it was hard to go inside churches with children. But, in my view, there was more zeal. Today, there are plenty of open churches, they aren’t packed, but it seems there is less zeal. However, I don’t try to follow “the order of the day”. My spiritual father kept saying to me: “Take care to control yourself, take watch over yourself! That is the most important thing.” And he suffered a lot of persecution: he was imprisoned, driven away from the Lavra…

—In the USSR intellectuals would often go to church to express their protest, thinking: “If the Soviet Government bans this, then it must be good.” But now that the Soviet Union no longer exists, some of them have left the Church. Why did you stay?

—True, such things did take place. But I didn’t join the Church as a dissenter to voice some protest; I came there because I had found “the one thing needful” regardless of times and powers that be. So for me your question is identical to this one: “Why do you live?” Church is life for me. It is not about politics—it is about salvation; these are two different “classes” in terms of semantics and importance.

Icon of the Holy Theotokos, “Joy of All Who Sorrow”

Icon of the Holy Theotokos, “Joy of All Who Sorrow”

An icon from the Convent of St. Stephen of Makhra (the Vladimir region)

An icon from the Convent of St. Stephen of Makhra (the Vladimir region)

The iconostasis of the Holy Trinity Church at Khokhly, Moscow, designed by Alexander Lavdansk.

The iconostasis of the Holy Trinity Church at Khokhly, Moscow, designed by Alexander Lavdansk.

Christ Washing the Disciples’ Feet. Fresco in the lower Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Kulishki, Moscow

Christ Washing the Disciples’ Feet. Fresco in the lower Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Kulishki, Moscow

Venerable Stephen of Makhra and Sergius of Radonezh

Venerable Stephen of Makhra and Sergius of Radonezh

Frescos of the Kinovar Studio, founded by A. Lavdansky

Frescos of the Kinovar Studio, founded by A. Lavdansky

Frescos of the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Kulishki

Frescos of the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Kulishki

Frescos of the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Kulishki

Frescos of the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Kulishki

Frescos of the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Kulishki

Frescos of the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Kulishki

The Synaxis of the New Martyrs of the Russian Church

The Synaxis of the New Martyrs of the Russian Church

The Meeting of the Vladimir icon of the Most Holy Theotokos

The Meeting of the Vladimir icon of the Most Holy Theotokos

The Feodorovskaya icon of the Mother of God

The Feodorovskaya icon of the Mother of God

Frescos of St. Nicholas Church (village Ozeretskoye, the Moscow region)

Frescos of St. Nicholas Church (village Ozeretskoye, the Moscow region)

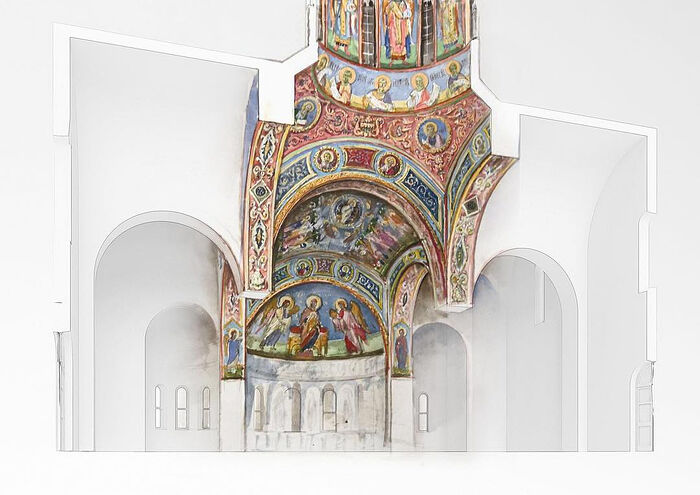

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

St. Antipas Church at Kolymazhny Courtyard, Moscow

Design of the iconostasis of the Church of Holy Theotokos. Designer: Alexander Lavdansky; Moscow, 2019

Design of the iconostasis of the Church of Holy Theotokos. Designer: Alexander Lavdansky; Moscow, 2019