Anton Ovsyanikov is a very interesting modern artist from St. Petersburg. We talked with him about his creative work, faith, his numerous trips to Mt. Athos, and whether it is easy to be an artist in our days.

—A prominent preacher, Archpriest Andrei Tkachev, wrote the preface to your wonderful album. How did that come to pass?

—I know Fr. Andrei Tkachev personally. I read his first book about seven years ago and was stunned by his diction and style! Then I contacted him through the website, “Collection of Sermons by Archpriest Andrei Tkachev”, and requested his email address. I wrote him that I had a bunch of questions about what was going on in Ukraine. At that time he must have been not too busy, so he gave me a very detailed reply.

—What year was it?

—2014. Then we exchanged phone numbers. At that time he already served at the church at Bryusov Lane in Moscow. One day I attended a service at his church and we talked. And in 2015 he and his wife called on us for cakes in St. Petersburg. So we spent a couple of hours together. Later, before the publication of my album, I asked him as a master of the word to write the preface to it.

Nature is a limitless resource and an abundance of work for an artist

An Evening in a Village. 2006. Canvas, oil. 60x80. By Anton Ovsyanikov

An Evening in a Village. 2006. Canvas, oil. 60x80. By Anton Ovsyanikov

—Landscapes painted in a masterly style take a special place in your work. Why is it that nature interests you the most?

—It’s true, although I don’t only paint landscapes. Initially I thought that this choice was dictated by circumstances. When I studied at the art college (mostly in the time of perestroika: between 1988 and 1992), I began to paint various landscapes together with my father and brother. To be honest, they were in high demand, so I easily made my living from these paintings. Afterwards, when I studied at the Academy of Arts (1996—2002), I mostly continued landscape painting. At the same time, I noticed that I had a bent for still life. But as time went by I realized that I had chosen landscapes because of my childhood memories. In our childhood and youth my brother and I would spend most of our holidays at our grandparents’ in a village in Belarus and would spend the rest of vacation with our relatives in the Carpathian region in Western Ukraine. It was a real rural life with all its beauty and distinctive features.

Subsequently, that nostalgia or, rather, the fond memories of childhood and the nature of those places played an important role in my life. I have always perceived myself as a man of nature. It is rather difficult for me to live in a big city. I regard living in a big city as reality and a necessity. And I try to escape to nature with great pleasure when I have a chance. Not necessarily to make sketches but just to walk and to go fishing. For me nature is the echo of Paradise, the place that mankind has not spoiled yet.

There are fewer such places on earth. Ideally, nature without human violence, loud music and human noise is associated with silence and the sounds it produces itself: birdsong, the rushing of a river, the murmur of a brook, or the sound of the wind. As St. Paisios the Hagiorite said, silence is close to prayer.

I would even say that nature gives us more opportunities for communion with God, to hear ourselves, meditating on more vital and eternal things. In fact, nature is a limitless resource and, therefore, an abundance of work for an artist. Sometimes it seems that my predecessors have already painted everything, and I have made quite a lot of landscapes too. But every time I find a new place I marvel. I feel drawn there and have the desire to paint a new landscape. I do believe that this has to do with my childhood, the nostalgia for my childhood memories and that period. Not everybody has had such a happy childhood. Not everybody has lived in the country; many just spent their vacation either in summer cottages or Pioneer camps. As for me, I had the blessing of observing nature to the utmost in my childhood. After all, most of our memories (both good and bad) come from childhood. Everything is formed during that period. I thank God and my parents that I had a happy childhood.

My brother and I had no other alternative

A Summer Day. 2005. Canvas, oil. 30x55. By Anton Ovsyanikov

A Summer Day. 2005. Canvas, oil. 30x55. By Anton Ovsyanikov

—Please, tell us how you became an artist.

—I grew up with my brother. There is one year’s difference of age between us. He entered the Academy a little earlier than I did. We both were born in Western Ukraine, in the small town of Kolomyya in the Ivano-Frankovsk region; my mother also came from there. My reposed father was a Belarusian.

And in some sense my brother and I had no alternative. Our dad set himself the task of making artists out of us. And—forgive the immodesty—not mere artists, but big names in art, famous and prominent artists. That is why we could not have become musicians or athletes, for instance. We never prepared ourselves for the technical, or military (although I have to confess that in early childhood I dreamed of being a sailor as I liked the uniform very much), or any other sphere. As soon as we learned to sit up as babies, pencils were put in our hands. And dad taught us. He even invented a system of drawing and called it “a scrawling game”.

Father’s Portrait. 2002. Canvas, oil. 70x60. By Anton Ovsyanikov

Father’s Portrait. 2002. Canvas, oil. 70x60. By Anton Ovsyanikov

Later, when we grew up, we had success at national exhibitions and we would even send our drawings abroad. I recall that it was a punishment each time we were forbidden to draw and our felt-tip pens and slate pencils were taken away from us. Though at some point it seemed to me that we were working like carthorses, knowing no rest. Sometimes I wanted simple boyish activities, say, to go fishing.

Then, nevertheless, after the eighth grade at school I began to study at an art college. And after that I unexpectedly and providentially ended up in the army.

—Why providentially?

—Because in 1992 I was still very immature in my worldview. For example, I didn’t have a clear idea of what I was going to do after college.

—You served in the Russian (and not the Soviet) Army, didn’t you?

—Yes, I did. Though the uniform was still Soviet. I was planning to join an institute in order to dodge the draft (as was then the custom in Russia). But the Lord intervened. I was collecting the documents to apply to the Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia (in St. Petersburg) to the Department of Graphic Arts. I believed that the main thing was to enter a university, and I would think about the future later. I was getting ready for the history and literature exams. But one fine morning at eight o’clock, if not earlier, an bus with a district police officer and a warrant officer from the military registration and enlistment office turned up, and I was literally taken out of my bed, led away and put into the bus (where several other guys who wanted to escape the army like me were sitting) and taken to the military registration and enlistment office.

It was in the army that my first serious conversion took place

A Mountain Pass. 2011. Canvas, oil. 30x40. By Anton Ovsyanikov

A Mountain Pass. 2011. Canvas, oil. 30x40. By Anton Ovsyanikov

—You say it was providential?

—Yes, but then seemed to be disaster for me. Though I had received notices from the military registration and enlistment office before, I had simply ignored them and refused to sign anything. And now Divine providence intervened. But at first I took it as a disaster. I was a homebody. And overnight I found myself in the “kingdom” of foul language, rudeness, friction between people, etc. But this did me good.

—Why and how?

—Firstly, I became stronger inwardly. It was then that I experienced my first serious conversion to God. By that time my mother had been consciously going to Church. She gave me many spiritual books to read, notably on Optina Monastery and the Optina Elders. She gave me the New Testament too. I read it from cover to cover, though then it was just to familiarize myself with the book. I experienced some sorrows as well. I realized that one of the shortest ways (though not the only one) to prayer is through sorrows. Secondly, if I had joined the Herzen University, my creative career would have been very different—that is obvious. Glory be to God for all things!

—And what was next?

—After the army my spiritual life, unfortunately, ebbed away… After all, it is about making efforts and forcing yourself! Absolutely! In a word, I was “neither fish nor fowl” for almost two years until my trip to my relatives in the Carpathian region in 1995. Something was happening inside me but I couldn’t figure out what exactly it was. It may have been my search for God that had started from the army. My interest in spiritual literature (the literature that could be found at that time) revived. When we arrived to our relatives’, it started raining and kept on raining for a week! In this weather I couldn’t go up to the mountains for a barbecue or explore the area anyhow. So I spent my time indoors reading various spiritual books that my aunt possessed. As far as I understand, that was providential too. Meanwhile, my mother and her sisters travelled to Pochaev Lavra and returned with lots of impressions. St. Job’s cave, his incorrupt relics, the footprint of the Mother of God, Her miracle-working icon… And she started trying to persuade us (my brother, me, and our two cousins, brother and sister) to go there. It was interesting and frightening at the same time because it was such a holy place… We worried a lot and, of course, the enemy didn’t want this pilgrimage to take place. At length we arrived there, glory to God! That was unbelievable. We came the day before the feast of St. Job—September 10 according to the new calendar. Those three days were extremely eventful! Firstly, I prepared for my general confession, recalling all the sins I had committed from my childhood. Secondly, all of us managed to take Communion on the feast. Thirdly (and that was very important), I saw more demonically possessed people there than I have ever seen before or since! Real possessed people, and not pretenders or mentally ill. I recall how a woman standing before the Pochaev icon let forth a stream of oaths in male bass voice using obscene language: “I am from TV! I am the prince of television!” Clearly, she was not speaking herself—the demon that was in her at that moment was shouting… Or how a group of robust men were trying to make another woman bend down to venerate St. Job’s relics, while she was resisting, writhing and yelling… I observed a lot of similar things. So, before leaving Pochaev I realized that demonic powers really exist! That was not fiction at all.

Cape Kirillov. Anzersk Island. Solovki. 2010. 45x80. By Anton Ovsyanikov

Cape Kirillov. Anzersk Island. Solovki. 2010. 45x80. By Anton Ovsyanikov

If there is demonic power, there must be the opposite. And I sensed it ever stronger. For example, the grace in St. Job’s cave (where he saw the uncreated light) was absolutely evident! And you can’t be somewhere in between: you are either here or there. I definitely didn’t want to be with the spirits I had seen in those miserable people. But, at the same time, I hadn’t come to God completely, or was afraid to. I had to decide. And it dawned on me that I had already made the decision. It had begun there, at Pochaev Lavra. On returning to St. Petersburg I forced myself to attend Sunday services no matter how hard and unusual it was. And I continued reading spiritual literature avidly! I can say that my conversion period was vivid.

—Reverting to your work, what further influenced your choice of Realist genres of art, namely landscape and still life?

In the Open Air. Belarus. 2019 —Our Academy, or Institute, the full name of which is “Ilya Repin St. Petersburg State Academic Institute for Painting, Sculpture and Architecture at the Russian Academy of Arts”, is our oldest academy of arts; it was founded under Empress Elizabeth Petrovna (1741—1761) and built under Empress Catherine II (1762—1796). It is one of our country’s main art institutions (if not the principal one) with rich traditions, where many of our distinguished artists studied and taught.

In the Open Air. Belarus. 2019 —Our Academy, or Institute, the full name of which is “Ilya Repin St. Petersburg State Academic Institute for Painting, Sculpture and Architecture at the Russian Academy of Arts”, is our oldest academy of arts; it was founded under Empress Elizabeth Petrovna (1741—1761) and built under Empress Catherine II (1762—1796). It is one of our country’s main art institutions (if not the principal one) with rich traditions, where many of our distinguished artists studied and taught.

What influenced me there? Our Academy specializes in the school of Realism, which is based on a drawing. Therefore, if you join it, you should be ready to accept the tradition of the Realist school and carry it on. But this is only done in theory because very many depart from it even in the course of studying. And after graduation they get carried away… Though it is the artist’s personal choice.

However, even if someone graduates from our Academy of Arts and then takes another path, he has studied all the basics: surface anatomy, drawing, painting, and composition. For me it was a natural continuation of myself. And I realized that after “winning liberty” I wouldn’t be carried away by anything and daub “Black Squares” [an allusion to the iconic painting by Kazimir Malevich with the same name.—Trans.].

I like to portray the truth of life. It is in my nature. I have always been a truth-seeker in my life. Those who possess this quality don’t feel very comfortable. Sometimes you have to pay for this. But the truth of life, realism (with a capital “R”) in all senses, both in life and art, is close to my heart.

Besides, I had begun to integrate Church life a year before I entered the Academy. That is why six years of studying were in harmony with the first stage of my life in the Church. For me it resonated with the poem by Hieromonk Roman (Matyushin) on beauty:

So be a mirror of God

And reflect as you cleanse yourself.

Otherwise do not touch beauty,

He who does not create does not distort.

The Lord is our Creator. And we humans are called to synergy. So, if we create something that contradicts the Lord’s plan and His nature, there will always be something unhealthy in this. A real artist should move in synergy, follow God, see the world in all its different guises in the rays of God, trying to convey this beauty to others.

The period at the Academy was very hard and intense for me, the first two years in particular. Then I felt a little better. I couldn’t believe that on Sunday I had a chance to make up for lost sleep after the week’s work. I nevertheless went to church services, and later during the day I could find some time for rest. This was followed by the next working week.

Peace and being honest with myself and God are important to me

Anton Ovsyanikov at a personal exhibition at the Apartment Museum of Joseph Brodsky. December 2013.

Anton Ovsyanikov at a personal exhibition at the Apartment Museum of Joseph Brodsky. December 2013.

—How do you feel as a representative of the Realist movement in painting? Are you on the fringes, or, to the contrary, part of a mainstream trend?

—The following words by Chesterton have crossed my mind: “A dead thing can go with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it.” I think the realm of contemporary art is very diverse. You can’t characterize it in a few words. But, of course, the school of Realism and Realist tendencies in the world of art of the past 100 years are just a shadow of what is going on there.

It is a complex question. I could reflect on this subject for hours. On the one hand, many still appreciate healthy realism in art. On the other hand, there is a aggressive minority that is trying to impose their worldview and way of life on the entire world. I know that if you bow to the mainstream, the movements, manners and subjects that are in demand, you will surely earn your bread and butter. You won’t have any financial problems. But peace and being honest with myself and with God are important to me above all. I realize that it is a thorny path. No one can guarantee you anything here. But I can’t do otherwise.

It is not to say that I am a rare bird, an outsider. Neither can I say that I am part of the mainstream. And what is presently going on in the world is a very long story. On the one hand, if we take modern people, a “clip consciousness” and the inability to comprehend long texts prevail here. Modern people have been writing and reading at the social media level at best for a long time. It is hard for them to grasp the meaning of serious works. In order to comprehend genuine art, including paintings, you need to cultivate taste in yourself so that you can understand that a painting speaks to you or its author speaks to you through it. On the other hand, many visitors wait for hours in lines at the Tretyakov Gallery to view paintings by Valentin Serov. Modern-day life is not easy to understand.

—There is a lot of light in your paintings, even where Russian nature is not depicted in bright colors. Do you do it intentionally or automatically? Or maybe my impression is wrong?

—I believe you are right and I am happy to hear that. It is done automatically. After all, there is inner light not only in sunny landscapes but also in those with a cloudy sky. But I don’t set myself this as a special task.

The Seacoast. Chalkidikí. Greece. 2008. Canvas, oil. 40x60. By Anton Ovsyanikov

The Seacoast. Chalkidikí. Greece. 2008. Canvas, oil. 40x60. By Anton Ovsyanikov

—Landscapes painted in Greece take a special place in your work. What attracted you to Greece so much?

—This country won my heart as far back as 1996, during my first stay on Mt. Athos. I have been under its spell ever since. Most of my trips to Greece are connected with Mt. Athos. I once attended Greek language courses in order to be able to speak with Athonite fathers. Greece opened up to me from a different perspective. My love for this country grew.

True, you can visit it as a tourist to enjoy this country as such—the sea, the sun, the mountains, and the blue sky. But I view Greece as the cradle of Orthodoxy. Russia embraced that faith through it. Though, for example, I have never been to Turkey (no offence meant). I don’t feel drawn to that country at all, though its landscapes are very similar to those in Greece and accommodation is cheaper. What interests me is the trinity of nature, culture and faith.

Thanks to my numerous trips to Mt. Athos I felt the desire to show more of it in my paintings. Though my Greek landscapes depict not only the Holy Mountain.

—Can you tell us more about your trips to Mt. Athos? What attracted you to Mt. Athos the most?

—In 1996, it was my first trip abroad. I just wanted to see the world and spend some time outside my native country. Then there was no internet, and I tried to find all I could about Mt. Athos from literature. I went there with my younger brother and our godfather (a monk of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra); we spent three weeks there, quite a long time for the first trip. It was important to me as a convert to see that Orthodoxy is not limited to Russia, that it is not exclusively the Russian faith.

After that trip my brother and I pined for Mt. Athos for a year and decided to take our father there. So the three of us made a trip to the Holy Mountain a year later. But Mt. Athos appealed to me so much that I wanted to visit the same places again. We even took boxes of paint (as we did during the first stay) with us and painted a little. But I found it hard to combine sketches and pilgrimage—I realized I had to either be a painter or a pilgrim, as one hindered the other. And afterwards other trips to Mt. Athos were arranged for me as if by themselves. For example, I cooperated with the Agion Oros (The Holy Mountain) publishing house and had joint projects with them.

After that I wanted to “recharge my batteries”, as it were. I remember that between 2008 and 2013 I didn’t visit Mt. Athos due to financial and other issues. But intuitively I felt an urge to visit the Holy Mountain again. Although the money was tight, I thought that if it was the will of God the funds would come, they would be sent to me. I began to pray—and the God-sent money appeared.

Anyway, Mt. Athos is worth visiting even without a knowledge of Greek. Many have already visited it, so it is not a wonder for them anymore. But when I visited it for the first time, many were stunned as if I had flown to the moon! And in our days it has turned into some sort of tourist business, and you can easily travel around Mt. Athos on a jeep; so you can make an “all-inclusive holiday” there.

—What did you gain from your knowledge of Greek?

—By learning Greek I reached a new level. Now I could communicate with the fathers and elders, and surely it was a miracle and the mercy of God, because few of our fellow-countrymen can easily get to an Athonite elder and speak in Greek with him. And true elders and true spiritual fathers still live on Mt. Athos. I must confess that three years ago I went through serious trials in life; they were so harsh that I think I survived only thanks to Mt. Athos and the prayers of Athonite fathers. If I had not gone there, I don’t know what would have become of me.

I still marvel that on Mt. Athos you receive answers to any questions instantly. True, the Lord is everywhere, and the Mother of God and the saints help us. But I have no doubt that there is the special grace of God on Mt. Athos. If you go there with reverence and pray that the Lord gives you the answer through someone, you are sure to receive it. You can often receive answers even without asking any questions.

I had very many various conversations with Athonite fathers and elders. For me Mt. Athos (not the least in difficult life circumstances) is like a breath of fresh air which provides you with vital energy for some time. You have your head above water for some time, but, unfortunately, the supply of energy doesn’t usually last for long. As you travel back you think that everything is going fine, you breathe regularly, you will live peacefully without worrying about anything and commend your life to God. But the world quickly takes you down from heaven to earth. A week or two will pass, and you will run out of this energy.

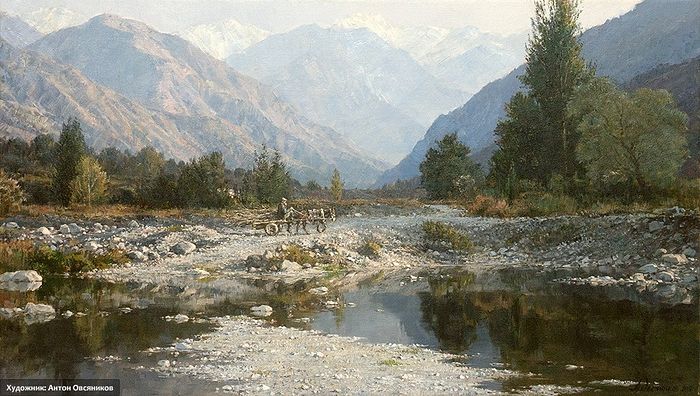

Ushkonyr Plateau. Kazakhstan. 2008. Canvas, oil. 45x80. By Anton Ovsyanikov

Ushkonyr Plateau. Kazakhstan. 2008. Canvas, oil. 45x80. By Anton Ovsyanikov

—How did you end up in Kazakhstan and how did it also captivate you in some sense?

—This was another interesting story. Through an artist from St. Petersburg, I got in touch with the art gallery in Almaty and worked with it for some time. Then they invited me along with several other artists to a creative trip and asked us to prepare an exhibition on a theme related to Kazakhstan. The gallery staff covered all our expenses. They showed us wonderful places for two weeks. We spent four days in northern Kazakhstan and ten days in Almaty and its surroundings. Those places were engraved on my heart. Perhaps this echoed my childhood memories of the mountains. As I said, I would spend some of my holidays in the Carpathian region of Western Ukraine. That is why the Kazakh mountains reminded me of something so dear to my heart. I adore such places: crystal clear rivers in the mountains, rocks, fir-trees or steppes. That was something dramatic and unexpected. I had been used to Russian and Greek nature; but in Kazakhstan I saw riders, dogs, yurts (nomad tents)—all of which reminded me of the paintings by Vasily Vereshchagin and his “Southern Series.” That is what I call life in nature, under the open sky, in the steppe. I depicted not only nature but also people and their everyday life.

I haven’t visited many places so far. If I had visited them all, they would have probably fascinated me like Kazakhstan or Greece. It is important for an artist to have new emotions and new impressions. When you get these emotions, you feel that something calls out in your soul, that there is some response. For example, I haven’t been to Thailand and Bali; but I see pictures of these places on the internet and realize that they, though beautiful, are not my type of countries. I don’t feel drawn to the tropics.

—Why is it that some places resonate with your soul and other places don’t?

—It’s difficult to explain. That’s an enigma, a mystery. I don’t know. Though I assume that if I were to see an Eastern market, an Asian bazaar or something like this, I would gladly depict them. I saw these in Vereshchagin’s paintings and on pictures taken in Tunisia: carpets, metal and copper pots and dishes, etc. That’s interesting.

Art is not spiritual life but the life of the emotions

Theophany. 2002. Canvas, oil. 125x200. By Anton Ovsyanikov

Theophany. 2002. Canvas, oil. 125x200. By Anton Ovsyanikov

—Is your religious faith reflected in your creative work anyhow? Do you see and realize any interconnection here?

—That’s a good question. Others have already asked me whether the faith helps me in my creative work or impedes my progress. Curiously enough, there can’t be a single answer. On the one hand, it certainly helps. I always pray before painting, make the sign of the cross, read the prayer to the Holy Spirit and ask for God’s blessing. I am aware that the Lord gives His help and inspiration. You don’t always have inspiration. When you have it, you understand that you did not paint alone, that someone helped you during the process. There is a parable song by the renowned Russian Orthodox singer and songwriter Svetlana Kopylova, A Brush in the Hands of God, about a talented artist who first believed that he was a man of genius but eventually came to understand that the talent was not his, and he, like every human being, was just a brush in God’s hands. This doesn’t apply to every artist, though.

On the other hand, there was Elder Sophrony (Sakharov). In his youth he pursued his artistic career. It was his great inspiration, he literally lived by art. Every time he went to sleep he would muse on the painting he was creating. And his journey to Orthodox faith was a thorny one. He used to say: “Art requires the whole person, so amateurism is not allowed here. Likewise, prayer requires the whole person. You have to choose.” He was a striking and somewhat radical person, so he chose prayer. Fr. Sophrony became a monk and ended up on Mt. Athos.

However, there are some people who combine both. And for some there can’t be half-measures: either one or the other. Fr. Sophrony chose prayer. Of course, I am not a person of high caliber like him. Meanwhile, I understand that for non-believers art can be a sort of surrogate—they call culture and art “spiritual life”, but they are not spiritual life at all! Let’s call a spade a spade: It is a life of the emotions in its different forms and qualities. The spiritual life is a life in the Spirit. Those who wholeheartedly devote themselves to art can succeed in it to a higher degree. Clearly, not all of them are Orthodox Christians; there are also Catholics, Protestants, agnostics, and so on. There were religious artists too. But when it comes to Orthodox artists, or, to be more exact, Church artists, then we should think and recollect whether they exist or have ever existed. If we take Russia, in the nineteenth century most of them were baptized and took Communion. As for their relations with God and the Church, this question has yet to be examined separately.

—Returning to my question: Does the faith help you or not?

—It does help me. I can’t imagine my work without faith. And my faith is reflected in my creative work. That is of primary importance. I am not speaking about the subjects. Take Mt. Athos: you can just depict it. But in order to depict the Holy Mountain with feeling, putting your heart into it, you need to love the place. But anyone who has developed professional skills can depict its architecture and landscapes. Why not? Here are Mt. Athos and its monasteries which are 1,000 years old. As for me, faith does help me.

What is an Orthodox artist? He doesn’t necessarily depict churches and monasteries. The 1990s saw a peasant-style period of Orthodox art. But Orthodoxy in creative art doesn’t necessarily presuppose ringing of bells. You may not say word about God, but your creative work will be genuinely Orthodox—it will be about God. I have a number of portraits of elders: I painted some for myself, some by request and some as gifts. You need to understand, love and feel the elder in question deeply. You must know his life well and not just depict his head, arms and legs. You may paint a cow walking towards the pond, and it will be depicted with great love because you represent the cow as a creation of God. And this painting will be more Orthodox than a peasant-style one.

But in some sense faith can also obstruct. Because you understand that the purpose of life is neither art nor creative work. True creative work is a part of your life. You need to set and rearrange the list of priorities. I hope that I have done it correctly and try to hold to this. Nothing has taken God’s place in my life since the day I entered the Church. There is a place for everything, and everything in its place. We should put God first, and all the rest is lower on the list. Creative activity has its place too. But if it becomes the top priority, everything turns upside down.

I hold that every man (the mission of the woman is to be a wife and a mother, in my opinion) should have his life’s work. However, if a man, for instance, can do nothing, considers himself a church person, has barely anything to live on, and prays day and night, then his place is at the monastery. Of course, this is a good and right path, too.

Moreover, art may become an idol that you worship, which contradicts the second commandment: Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image… (Exod. 20:4). That’s a problem. Meanwhile, in order to become a real artist and master you need to work very hard. I was told about the 10,000-hours concept: in order to become an expert in your field you need to practice a minimum of 10,000 hours in your sphere. This rule doesn’t really work in art: here you can never assert that now you can do everything and so you can sit down and relax. Permanent inner growth and critical thinking about yourself and your work are necessary. Sometimes you think that your painting has come out pretty good; but once you look at the great masters’ creative products, you see that they are beyond comparison. You must see the horizon and learn your entire life.

In order to be an honest artist and make a living by your trade you should be prepared for difficulties

The hay is delivered. A sketch. 2002. Canvas, oil. 40x60. By Anton Ovsyanikov

The hay is delivered. A sketch. 2002. Canvas, oil. 40x60. By Anton Ovsyanikov

—Is it possible to make your living and provide for a family by painting? Isn’t it a risky trade in terms of material well-being?

—From a perspective of material prosperity it is quite a risky occupation. Though, curiously enough, it allows you to sustain yourself and support your family. That is not easy yet possible. I sold my first painting when I was about fifteen, and I haven’t done anything other than paintings to earn my crust ever since. So, answering your question, I’ll say that it’s possible, adding that only with the help of God. It even allows you to maintain your family.

—Seven fat cows and seven gaunt ones (cf. Gen. 41).

—That’s a good comparison. It depends. If you live on your own, you may even live on bread and water, however you please. But if you have a family, you are responsible not only for yourself. Regarding this, when I am asked about children and whether they should study to be artists, I answer that you need to think very carefully. It is fine as an interest or a hobby, why not? But in order to be an honest artist and make a living by your trade you should be prepared for difficulties and not create illusions.

—Why?

—Art is not one of the necessities of life. Clearly, if someone has good savings, he can spend a considerable amount and afford to buy a work of art, a painting. You should be a fairly well-off for that. Or you should paint in the “for everybody” category by making cheap paintings of average quality and selling them on Nevsky Avenue or other tourist places. Whether it’s true art or not is another question. But you will make a living by your trade.

—And then you can earn more, right?

—Perhaps you’re right. But this situation is so complex that I am not sure. For example, the following question was discussed somewhere: Does the fact that people buy many of your paintings indicate that you are a good or a bad artist? How would you answer?

—It depends.

—Absolutely right. You may be neither good nor bad. Maybe they buy your creations because you are a honored artist. Or they are doing it because you are a hyped-up “naked emperor” [an allusion to the famous short tale The Emperor’s New Clothes by the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen.—Trans.].

—In that case your work is in demand because you satisfy bad tastes.

—Sure. Or no one is buying your paintings. Are you a bad or a good artist after that? It depends. It can be either. There can’t be a single answer. As for me, if it were impossible to make a living from it, I would have changed my job and left painting to being a mere hobby long ago. But with the present global crisis and other issues, I am aware that my colleagues (especially in Russia) are having a hard time. There are various art markets. Some artists target the Chinese market because the Chinese appreciate our Realist genres very much. For others the target market is America, for others it is Europe. These niches are very different and they don’t intersect. If your paintings are in high demand in China, it doesn’t mean that you will have the same demand in America. But you have to exist in this world with the hope that you will be able to live by your own labor for the rest of your life. I really hope so.

There are market trends, and there is the mainstream—and you have to choose. If you prefer market trends and have certain professional skills, you will do something technical with hardly any trouble. Okay, that’s your choice. But if you want to follow your path and not digress, get ready for sorrows. We live in a material world; and we need not only to earn our daily bread but also get clothes, take care of our health, buy canvases and paints, brushes and materials, frames etc. All of this costs money. I personally experienced various periods—there were times of material well-being when things were going fairly well and even fine, and times of slack when I was absolutely penniless and thank God there were people to borrow money from… An unstable income when you have no salary… Sometimes I am on the rocks for a month; another time someone buys my paintings so I can pay off my debts and last out till next month. But it is obvious that this path is not for everyone.

Open Air near the Sea of Azov. 2017

Open Air near the Sea of Azov. 2017

—Do you get away to nature when you paint pictures?

—No, I don’t. We should distinguish between working in the open and working in the studio or the workshop. True, the Impressionists could create complete pictures right “in the wild”. But sketches are sketches, and paintings are paintings. I too go to countryside to do sketches from time to time. Since recently for me this has become a time for rest and “recharging my batteries”. I try to do it regularly, but sometimes I have too many cares and work to do. Sometimes it’s hard to activate my efforts, though I try my best. As for paintings, I paint them in my studio. Thank God, now I have a studio. Previously I either leased a room in a shared apartment or worked from home. Though I worked from home nearly throughout my career, it is not very convenient; an artist must have a workshop as it is a very important space. This is his world, his “kingdom”.

—What are you currently working on?

—It has already become my custom to paint landscapes. It’s a kind of repose. Besides, as a form of subsistence for two years now I have worked for an American gallery, making still lifes on the theme of the Wild West for them. They even sent me some specific items as American attributes. Thus I earn a living. Even so, I am not ready to do whatever they ask me to. We looked for an appropriate theme for me and finally decided in favor of an austere, cowboy-and-lumberjack style. When I was asked to create something with ballerina gloves, fans and watches, after much resistance I surrendered, but nothing worthwhile came of it (in my view). I kept saying to them that they shouldn’t have pressured me. That was not my theme, I don’t like it, I don’t live by it, that’s not my favorite subject.

By agreement with them now I paint what I like. For example, saddles, lassos, horseshoes, stirrups, ropes, etc. Simple, democratic things that I like and that are close to my heart. In this case, I believe, it is a good symbiosis because a painter should have a chance to make both ends meet, and that’s a good combination of the commercial and the inward without exerting pressure on the inward or making compromises. At present I mostly work on still lifes. Sometimes progress is fast, sometimes it is slow. At times for variety’s sake I need to do something for private satisfaction, for my spirit. Then I sit down and paint a landscape.

A Tranquil Evening. 2008. Canvas, oil. 60x105. By Anton Ovsyanikov

A Tranquil Evening. 2008. Canvas, oil. 60x105. By Anton Ovsyanikov

—How long does it take you to make a painting?

—From one day to a week or two depending on the size and complexity. On average it takes me three to five days to do a painting.

—Do you ever have non-working days?

—Yes, I do. As a Christian I observe Sunday and never work on that day. I am a free person and I don’t work at a factory with its shift schedules. I don’t work on the twelve great feasts either. During Great Lent I try to attend church services more often, especially on the first and final weeks of Lent. This concerns other important days of the liturgical cycle too. I’ve made it an unalterable rule to work six days and dedicate Sunday to my Lord. Occasionally I can have an extra non-working day or two, or more—that’s going in a dynamic rate. And, most importantly, there is no need to force me to work. I do possess this trait and I am indebted to my dad for this.

As a rule, the work of artists is such that they are not obliged to work their eight-hour shifts. As for painters, they hardly ever work eight hours a day. If I’m not mistaken, Isaac Levitan used to say that he worked only four hours a day. My working day is largely the same, or only slightly longer or shorter. But in that case you seemingly have a lot of spare time, so you must be free most of the day? Or is it like your working day finishes, you get home and don’t care about anything? There is “no cure” for being an artist! You think about your paintings permanently. For example, you notice something beautiful on your way, this triggers some mental process in you and you start thinking about your future painting. In addition, there are a lot of related things to do: stretch out the canvases, prime the board, go and buy new frames and materials or tidy up the studio, and so on.

I had a brilliant period of creativity with the Kazakhstan series when I put my heart into the creation of those paintings—I recall this now and again. I remember falling asleep with the future painting in my mind, thinking: “I wish I could nod off soon, my brain can’t relax and I can’t fall asleep.” And I would wake up with the thought that now I would have my breakfast and sit down at my easel straightaway. Or the day has ended, and you are already selecting some photos and sketches and thinking on your future painting. Sometimes I have to stop myself forcibly. So being an artist means having irregular working hours. There is no such thing as sitting through your working day in the office, coming home, not worrying about any problems, and proceeding to your personal life. For me my creative work is also my personal life.

You can view a picture gallery by Anton Ovsyanikov here: "Artist Anton Ovsyanikov. Selected Works."