For all of us, becoming acquainted with the New Confessor Nicholas (Mogilevsky) is like finding treasure. On the twentieth anniversary of the uncovering of his relics, Hieromonk Yakov (Vorontsov), cleric of the Ascension Cathedral in Almaty, Secretary of the Commission for the Canonization of Saints in the Metropolitan District of Kazakhstan, speaks about this holy archpastor.

God hears those who hear others; or, the Gospel in action

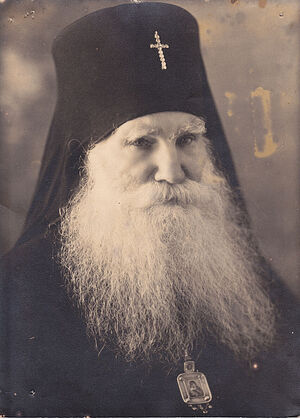

Archbishop Nicholas (Mogilevsky) I recall that from our childhood, like many other Almaty residents, we used to visit the central city cemetery to stand under the canopy between two graves and pray to our holy hierarchs of Kazakhstan: Metropolitan Nicholas (Mogilevsky) and Metropolitan Joseph (Chernov). We felt this Paschal, ineffable joy, especially when we celebrated the memorial service and sang together, as Vladyka Nicholas liked to do.

Archbishop Nicholas (Mogilevsky) I recall that from our childhood, like many other Almaty residents, we used to visit the central city cemetery to stand under the canopy between two graves and pray to our holy hierarchs of Kazakhstan: Metropolitan Nicholas (Mogilevsky) and Metropolitan Joseph (Chernov). We felt this Paschal, ineffable joy, especially when we celebrated the memorial service and sang together, as Vladyka Nicholas liked to do.

“Sing, my friends, sing! Always sing, whether you can or can’t. Listen attentively: everybody has an ear for music, even if it’s undeveloped. After all, you are not deaf and can hear a conversation. Likewise, you will hear singing if you begin to sing continually and listen to singing. If initially you have little progress, then sing softly, but persevere,” the hierarch would instruct and explain further: “As long as you sing, you pray more attentively. Note how hard it is to keep your mind from wandering during prayer when you are a beginner. But if you sing your prayer, it will be always with you. Once you stop singing, thoughts will fill your mind and it will ‘wander all over the place’. And it is impossible not to sing when your soul sings during the service!1”

The New Confessor Nicholas was canonized—that is, the Church recognized that the Lord revealed Himself in this world through His servant Nicholas. That is why even before his canonization we experienced such joy during memorial services at the cemetery, as in church…

Metropolitan Nicholas himself wanted to be buried on the territory of St. Nicholas Cathedral in Almaty. In the Soviet era, militant atheists desecrated this holy place in every way possible—it housed a museum of atheism, stables and various other establishments. All its frescoes, furnishings and decorations were destroyed. Metropolitan Nicholas worked to restore this cathedral (dedicated to his heavenly patron in monastic life) with great devotion and served in it for many years. When he was terminally ill, he requested to be buried there, but his application was denied by the authorized representative of the Council for Religious Affairs in Kazakhstan.

Archbishop Nicholas in Zhambyl. Far right: Fr. Savva Kotlyarov (the father of the future metropolitan of St. Petersburg and Ladoga); center: Glikeria Efimovna (the future metropolitan’s mother); right: the youth Vladimir, future Metropolitan of St. Petersburg

Archbishop Nicholas in Zhambyl. Far right: Fr. Savva Kotlyarov (the father of the future metropolitan of St. Petersburg and Ladoga); center: Glikeria Efimovna (the future metropolitan’s mother); right: the youth Vladimir, future Metropolitan of St. Petersburg

The authorities allotted him a plot at an ordinary cemetery and promised that afterwards they would give permission to erect a chapel over his grave (they didn’t keep their promise). It was not until many years later that a canopy was installed. And on September 8 twenty years ago, the saint’s wish came true—by the will of God his holy relics were uncovered and translated into St. Nicholas Cathedral, where they rest in a decorated shrine.

Almaty residents and guests (multitudes of pilgrims come here even from far away to venerate the holy archpastor) mostly visit two places associated with the new confessor’s memory: St. Nicholas Cathedral (where he served and where his relics are kept) and his former grave at the cemetery.

The holy hierarch hears everybody, as he did in his lifetime. His holiness is not limited to his confession of the faith—he was also a great man of prayer. The Lord bestowed upon him the gift of prayer for everything he had humbly endured for His sake, for following the narrow path of the Gospel commandments and guiding the clergy and laity.

Many testify what a great consolation they receive at his shrine and how speedily help comes.

He who succeeded his executed predecessor

Though the hierarch was very meek by nature, he performed mighty apostolic labors in Kazakhstan. He shares the same reputation of Archbishop Zephaniah (Sokolsky; 1799–1877), the first local bishop who came here in the second half of the nineteenth century when there was no real diocese in Kazakhstan; true, there were some scattered parishes, but it was Vladyka who as a missionary built this diocese from scratch.

Just as Archbishop Zephaniah once taught the clergy he ordained how to sing, and would bring together the singers he chose from among the parishioners, Metropolitan Nicholas did the same. Born to the family of a priest where traditions of church singing were particularly revered, later in his native Ukraine as a parish school teacher he would teach children and youth how to sing, in order to distract them from pernicious influences and wantonness. Here in Kazakhstan he also taught people the troparia and kontakia of feasts, other Church hymns that then weren’t known by many, explaining their liturgical meaning, talking a lot with people, and thus discreetly catechizing them.

These were turbulent times, when atheists aimed to corrupt people morally. St. Nicholas’ immediate predecessor at this diocese, New Martyr Tikhon (Sharapov), had been executed by firing squad at the Zhanalyk Shooting Ground in 1937, after serving there for less than half a year. Such was the place to which St. Nicholas was appointed.

Then, the Diocese of Kazakhstan as such no longer existed and churches were closed. Of course, the faithful prayed at home, clergy would secretly serve the Liturgy, baptize, perform weddings and funeral services at their homes… But all of that was “in the catacombs”. How could someone legalize church life in that environment?...

How God saves many, acting through His true disciples

Vladyka’s health was undermined by prisons, exile, hunger, and cold—he had no roof over his head and lived on charity. Once he was so emaciated that he fainted. He would have died if a Tatar hadn’t picked him up. It took place in Chelkar, a town in Kazakhstan where he was sent after one of his arrests. He was thrown out of a train at night in his undergarments and a torn, quilted jacket. Local old women took pity on him, bringing him a pair of patched-up felt boots, a hat and a pair of old trousers. One of them sheltered him in a shed with a cow and a pig. The saint didn’t reveal to anyone that he was a bishop… Let’s recall that St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, a great universal saint, at one time literally lived in the streets without revealing his identity.

And in this situation the Lord Himself intervened, commanding a Muslim, an adherent of another religion, to nurse the man lying unconscious in the middle of the street back to health.

The amazing book, Metropolitan Nicholas’ biography cited above, contains the following dialogue in the hospital where the Tatar had taken the unconscious St. Nicholas and then returned to take him to his house:

“Why did you decide to take part in my life and show me so much compassion? After all, I’m a total stranger to you,” the metropolitan asked.

“We must help each other. God told me to help you and save your life.”

“How did God say it to you?”

“I don’t know how. When I was driving somewhere on business, God told me, ‘Take this old man. He must be saved.’”

Thus the Tatar took him to his house. After long efforts he even arranged for Vladyka’s spiritual daughter, Vera Afanasievna Fomushkina, to be transferred to him. She had been serving her term elsewhere for sending the imprisoned archpastor prosphora and church wine to celebrate the Liturgy. And she then revealed to the people of Chelkar that it was he who had lived by begging in the town.

Archimandrite Job (Gumerov) of Sretensky Monastery By the way, St. Nicholas was thrown out at the snow-covered small station of Chelkar in 1942, several days after a boy named Shamil had been born to a local Tatar family. His mother, Nagima Khasanovna, was totally emaciated by starvation, because the family would give everything they had to the [war] front. Afterwards that very boy was baptized into Orthodoxy with the name Afanasy, became a priest, and was later tonsured a hieromonk with the name Job at the Moscow Sretensky Monastery. Now he is known as Archimandrite Job (Gumerov). His two sons also chose the priesthood and his daughter chose charity work.

Archimandrite Job (Gumerov) of Sretensky Monastery By the way, St. Nicholas was thrown out at the snow-covered small station of Chelkar in 1942, several days after a boy named Shamil had been born to a local Tatar family. His mother, Nagima Khasanovna, was totally emaciated by starvation, because the family would give everything they had to the [war] front. Afterwards that very boy was baptized into Orthodoxy with the name Afanasy, became a priest, and was later tonsured a hieromonk with the name Job at the Moscow Sretensky Monastery. Now he is known as Archimandrite Job (Gumerov). His two sons also chose the priesthood and his daughter chose charity work.

“My tender-hearted mother may have given him alms, and he prayed for her and her family’s salvation” Fr. Job writes about His Eminence.2 “I am convinced that the saint’s presence, the celebration of the Divine Liturgy, and the combined prayers of other pious Orthodox Christians had a salutary effect not only on the worshippers but also on all the town residents. It is known that a righteous man upholds the city. So, reflecting on my journey to Orthodoxy and giving thanks to God, I regard St. Nicholas (Mogilevsky) as one of my patrons. At that time, Divine grace may have touched my child’s heart.”

After finding refuge, Vladyka Nicholas began to serve, baptize, hear confessions and give Communion at home. At the height of the Second World War, people didn’t know what had become of their loved ones or whether they would come back from the front; many received “fallen in action” notices. The archpastor consoled everybody. People kept flocking to him in their pain.

Wherever he was, he always served people. He did it even when he concealed his identity, as at the hospital where, once he got a little better, he would bring a bedpan to a fellow-patient, give some water to another, or straighten another’s bed. He always radiated peace, joy and affection. Everybody called him “good grandpa” at the hospital without fully understanding who was near them. We can draw some parallels between the ways of life and images of the New Confessor Nicholas (Mogilevsky) and St. Nicholas of Myra, his heavenly patron.

The experience of both holy hierarchs, St. Nicholas of Myra and St. Nicholas of Alma-Ata [an older, Soviet name for Almaty.—Trans.], indicates that if a person accepts the cross from God and bears it worthily, the Almighty won’t leave him. This invaluable lesson may be very useful in our extremely rebellious times.

Vladyka Nicholas at the “Immortal Regiment” march

Then, in 1945, St. Nicholas was appointed as the ruling hierarch of the Diocese of Kazakhstan and Alma-Ata, which had been previously vacant for eight years. And before that he had borne the cross of sorrows and hardships with the whole nation. Prior to his consecration he had set up a chapel in the house of a woman who had lost all her children in the war. He would hear confessions, talk and console people there.

So when we were preparing a photo exhibition on the occasion of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Great Victory this year, dedicated to clergy and the faithful who made a large contribution during WWII, we included Metropolitan Nicholas in it. He was serving the Proskomedia when the beginning of the war was announced.

Archbishop Nicholas in the center.

Archbishop Nicholas in the center.

He came out to people and said:

“God is not in might but in truth,” repeating the words of St. Alexander Nevsky, the 800th anniversary of whose birth we are marking this year.

Thus from the very beginning, the archpastor instilled in his flock faith in victory.

St. Nicholas was busy helping people his entire life. He was an absolutely approachable person. And when he was officially assigned to the large Diocese of Kazakhstan, he lost heart. The following note from his diaries survives:

“By Patriarchal decree I have been appointed to Alma-Ata with the title ‘of Kazakhstan and Alma-Ata.’, to the city of greenery and fruit, the beautiful capital of all Kazakhstan [it was the capital of Kazakhstan until 1997.—Trans.].

“The word ‘capital’ confused my weak spirit and I asked to be sent to a small Russian town, but it appears that God wishes to increase the weight of my archpastoral burden. May Thy will be done!”

Now even aksakals3 ask him to pray for their sons who are drug addicts

Thus the elder, who had already gone through a great deal, tirelessly travelled the length and breadth of the enormous Kazakhstan Diocese, even to its remotest areas, always willing to have a personal contact with everyone, always personally blessing each member of his flock. With time thousands of people flocked to his services. Of course, churches couldn’t accommodate everybody, so people often worshipped outside. And when he died, around 40,000 people arrived to pay their last tribute to him.

Even non-Christians would come to Vladyka, seeking his blessing, counsel and prayers. And he received everybody with love. Even now you can often see Muslims standing at his shrine. There are lots of temptations connected with drug traffic in Kazakstan, with a lot of poppies and hemp growing in the mountains. So local elders come to the saint as to their last refuge to ask him to intercede for their sons.

Metropolitan Nicholas and Archimandrite Isaaky (Vinogradov). Under Metropolitan Nicholas the diocese was revived from non-existence. I recall the words of Archimandrite Isaaky (Vinogradov), Metropolitan Nicholas’ co-laborer, close spiritual son and successor, which he spoke in his funeral speech:

Metropolitan Nicholas and Archimandrite Isaaky (Vinogradov). Under Metropolitan Nicholas the diocese was revived from non-existence. I recall the words of Archimandrite Isaaky (Vinogradov), Metropolitan Nicholas’ co-laborer, close spiritual son and successor, which he spoke in his funeral speech:

“The purity of his soul was like a beautiful pearl.”

In truth Vladyka Nicholas is treasure for all who discover him, if only through publications.

In his lifetime he was already regarded as a living saint. He was an embodiment of meekness and love. Sometimes it is hard for us to comprehend and put the Gospel principles into practice, but through the saints’ experience this “science” is revealed to us.

The metropolitan has been and still remains a peace-maker (cf. Mt. 5:9). Such was the time people were living in (but when has it ever been easy?)—they suffered much, and many became embittered. After their experience of prisons and camps, some became stronger spiritually (as did St. Nicholas); but not everyone has such inner strength, and some were broken. There was an atmosphere of rancor and suspicion. He had to settle issues, find an approach to everybody, and heal their souls.

The whole Diocese of Kazakhstan at one time defected to Renovationism; most priests who returned to the Church were from among the schismatics. Even Vladyka’s secretary, Archpriest Anatoly Sinitsyn, had earlier been a married Renovationist archbishop. Later he was received into Orthodoxy as a layman and afterwards ordained; but he was an extremely difficult man till the end of his life. The saint had a lot of trouble with him but was patient and didn’t spurn him.

The metropolitan rejoiced whenever he managed to reconcile people with God or each other. As long as everybody was under the holy archpastor’s prayerful protection, in his presence everything was smoothed over; but after his death through human weakness things got worse again.

Metropolitan Nicholas with clergy and flock in Alma-Ata, spring 1955. Probably the feast of Pentecost

Metropolitan Nicholas with clergy and flock in Alma-Ata, spring 1955. Probably the feast of Pentecost

Those who ward off dangers; or, it is not a matter of education or trendy scientific theories

The memory of Vladyka lives on, and people venerate and love him dearly. Almost every church in Kazakhstan has an icon of him, often with particles of his relics—although many people come specially to Almaty to venerate his main shrine. On his feast-day (as was the case in his lifetime) the church can’t accommodate the pilgrims—up to 15,000 people come. There are books and films dedicated to Metropolitan Nicholas; a medal and an order that bear his name were instituted…

The love of the people of Kazakhstan for their two saintly archpastors—Metropolitan Nicholas (Mogilevsky) and Metropolitan Joseph (Chernov; he hasn’t been canonized yet) is simple, like that of children, and based on trust. And both archpastors had the same love—accepting and not condescending—for their flock. It is not a matter of erudition or education, or of trendy scientific theories.

The people of Kazakhstan believe that from the time these two great archpastors arrived in this land sanctified it by their prayers, their Christian labors and faith in the Crucified Lord, we have had no catastrophic earthquakes or mud flows in our seismically active region. Before them, earthquakes posed a real danger.

On being princes not of this world

Since my childhood, Metropolitan Nicholas has been a great spiritual authority for me; although at the time he was not yet canonized. My first church obedience was connected with his memory—it was watching over the candle-stand of the Kozelshchansk icon of the Theotokos. Meanwhile, my friend Roman kept an eye on the candles in front of an icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker. These are two large icons on either side of the royal doors of the St. Nicholas Cathedral in Almaty. Eventually we both became monks, and Roman even received the monastic name “Nicholas” in honor of New Confessor Nicholas (Mogilevsky).

Recently Tatiana Klochkova, a senior parishioner of St. Nicholas Cathedral, told me how the Kozelshchansk icon of the Theotokos ended up at the cathedral. A family had moved to Almaty from the Penza region and brought this icon. It is a huge icon, which originally must have been in a church; churches across the country were being closed. Some took church items home, in many cases trying to preserve icons. But when one day their neighbor, an old woman, called on them, she saw this icon and told them that it had belonged to the Church, that a bishop had been appointed to our diocese, and that the church had been reopened but it had no icons.

“Give the icon to the church!”

But the family asked a very high price. When the old woman came to Vladyka and told him the price, he said:

“I won’t have such money till the end of my life!”

Used to wandering, he lived extremely modestly for the rest of his life. He would eat very little, and only simple food. He would sew himself cassocks from pieces of unbleached linen, thus imitating Sts. Sergius of Radonezh, Seraphim of Sarov and Nilus of Stolobny Island on Lake Seliger, in whose monastery he was tonsured. “I would feel uneasy conducting services for our venerable fathers while dressed in brocade. They served in humble vestments and attained great holiness!” And Vladyka’s flock mainly consisted of simple people and hard workers, and he thanked God when any of them brought a penny to church.

Metropolitan Nicholas often recalled his grandfather, who too was a priest and served in the same parish for sixty years, with no desire to move to more lucrative places. He instructed Vladyka’s father to serve for Christ’s sake and not for money:

“My son, never chase after money! When asked how much an individual service is, answer ‘a penny.’ And you will never be in need: people will appreciate your disinterestedness and support you.”

This is precisely what his grandfather, father and the archpastor himself did. Just as our Lord is the King not of this world (cf. Jn. 18:36) and His Heavenly Kingdom is within us (cf. Lk. 17:21), so Vladyka “reigned”. It is known that bishops are called “princes of the Church”; but this “principality” is not of this world—it is within us.

So when the old woman told the archpastor what an astronomical sum her neighbors were asking, he said:

“While I pray to God, please go to them every day and keep asking.”

In the end the family donated icon to church for free.

The fact is that the history of the Kozelshchansk icon is connected with Ukraine—the land where Vladyka Nicholas was born and then served and worked as inspector at the Poltava Theological Seminary. Beyond all doubt, this icon gave him great consolation in Kazakhstan, far from his homeland.

On how to pacify potential revolutionaries

Vladyka himself came from a very pious family. His grandfather and father were priests, and his mother was very religious. His grandmother, though she had little education, knew the Lives of many saints by heart and recounted them to her grandchildren so vividly that they imagined the saints’ ascetic labors and inner struggle very clearly. It was her living faith and not just dogmatic erudition. So his family instilled Gospel purity and simplicity in the future metropolitan from infancy.

Just imagine: he worked as the inspector at the Poltava Seminary. It is a managerial position, and young people don’t like people in such positions. It was just before the Russian Revolution, and everyone was stirred up. Moreover Ukraine has always been a difficult epicenter. There was a very tense atmosphere, with riots, threats and violence. The situation become so aggravated that once the seminary administration decided not to allow the students to go home for the Nativity. The enraged seminarians furtively slipped a note to the future metropolitan, reading, “Let us go home for the Nativity or you’ll bathe in your own blood!” But the saint wasn’t taken aback. He simply went to the classroom with that note and called the students out one after another, saying,

“Read it aloud.”

“I can’t, the text is illegible,” said the first one, blushing to the root of his hair. The other students did the same. Thus he brought them to repentance.

On top of that, the students took to playing cards. But the metropolitan through the keenness of his wit saw through students and could always expose their tricks. While they were playing cards, one of them would be on the lookout: “Once you see an outsider, start talking about the book you’re supposedly reading. That will be the signal.” But Vladyka came to them through the back door. The boys were shouting in their excitement, “I’ve got spades!!”—“And I’ve got clubs!!”

“And I’ve got diamonds,” Vladyka said, as if confidentially.

The card players turned around. It was like a scene in a silent movie. They were about to panic, thinking, “Now we’ll be expelled from the seminary!” But he didn’t give them away. At the same time, he had the striking ability to bring them to repentance. As a result the seminarians came to love him. But he was strict with them, for their own benefit.

Through the purity of his soul the hierarch from his youth possessed a wonderful quality: the ability to transform people around him. Everybody was drawn to such an archpastor. So, the saying we’ve all heard applies to him: “If all priests were like you, there would have been no need for the Revolution.”

What is more important than “academic tasks” for pastors and archpastors?

His archpastoral ministry coincided with the period of the explosion of all the human conflicts that flared up in social life from time to time. There was already a schism and a movement for the autocephaly in Ukraine back then, and later he had to deal with Renovationism in the Dioceses of Tula, Orel and Kazakhstan.

As a soldier of Christ he stood watch for Orthodoxy throughout his life! He stood for the unity of the Church of Christ and a life in the tradition of the Holy Fathers, as all the saints of Ukraine did!

An illustrative example is his graduate dissertation, “The Teaching of the Ascetics on the Passions”, which he wrote at the Moscow Theological Academy where he studied at the insistence of the Stolbny Monastery brethren. The reviewer was Bishop Theodore (Pozdeevsky), then rector of the academy. In it Bishop Theodore cites the author’s opinion on his research topic:

“We do not set ourselves academic tasks… Our goal is simpler and more specific: to learn for our edification from the ascetic fathers about such vital questions.”

And the reviewer writes further:

“The author stood by his statement and provided truly edifying reading for all who wish to learn from the Holy Fathers about how to struggle with the passions and gain salvation.”

And this is how Vladyka Nicholas lived his entire life: in the spirit of the Gospel and the Holy Fathers. He never philosophized; rather, as he instructed others:

“There is no salvation outside the Church. And there is no truth outside it; it is only in the Church that the Lord saves those who repent by His grace.”

Photos from the archive of the Commission for the Canonization of Saints of the Metropolitan District of Kazakhstan and Hieromonk Yakov (Vorontsov)’s personal archive