American fans of Monty Python will be familiar with the opening lines of William Blake’s poem, “Jerusalem” (and I apologize to my British readers for such an introduction). The poem was set to music in 1916 and became deeply popular in post-war Britain. The Labour Party adopted it as a theme for the election of 1946. It recalls the legend of Christ’s visit to England as a child (taken there by St. Joseph of Arimathea). Blake spins it out into a vision of the heaven to be built in the modern world:

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountain green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen?

And did the countenance divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among those dark satanic mills?

Bring me my bow of burning gold!

Bring me my arrows of desire!

Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire!

I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand,

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green and pleasant land.

King George V is said to have preferred it as a national anthem over “God Save the King.” It is, indeed, used as an anthem in a number of contemporary settings.

It has to be heard and understood in the context of its times. It was first published in 1808. Blake, interestingly, was an outspoken supporter of the French Revolution and a critic of the many darker elements of the industrial revolution that was, as yet, in its early days. That struggle is something of a theme that has continued through to our present day.

Though we often welcome the innovation and conveniences brought by industrialization and technological advances, we also lament the frequent tragedies found in their wake. The present environmental movement seems torn between a green world of naturalism and a super-technological world in which the digital age marries convenience to a tiny carbon footprint. The jury is still out on this latter possibility.

In Blake’s time, industrialization was new and often had the effect of displacing traditional workers. As a child, he lived near the Albion Flour Mills in Southwark, the first major factory in London. The factory could produce 6,000 bushels of flour per week and drove many traditional millers out of business. When the factory burned down in 1791, the independent millers rejoiced. Some have suggested Albion Flour as the origin of Blake’s reference to “Dark Satanic Mills.”

At the very time that industrialization was bringing prosperity to some, it created new forms of poverty among the “unskilled” (or “wrongly skilled”) poor. We live with the same thing today. The abandoned factories of the Rust Belt, where poverty and drug-addiction have replaced a once thriving industrial world, point to how intractable this aspect of modernity has become. Two-hundred years after Blake, our Dark Satanic Mills are generally off-shore. Their Jerusalem, our Satanic Mills.

The tremendous success of industrialization (for some) also created a deep, abiding confidence in the power of science and the careful application of human planning. As problems increased, so, too, did various plans and efforts to manage them. There grew up, as well, a sort of modern, industrialized eschatology. The Christian faith believes in the coming Kingdom of God. Already, various reformers and off-shoots of the Puritans had imagined themselves to be creating an earthly paradise. Their utopian visions became powerful engines of change and revolution. As the heads rolled in Paris, the crowds imagined them to be harbingers of a new world. They were – but not paradise.

A name deeply associated with the Christian adoption of this progressive thought is Walter Rauschenbusch (1861-1918). An American Baptist who taught and pastored in New York, he put forward works that would become foundational for the notion of the “social gospel.” The 19th century had seen something of a collapse in classical Christian doctrine in many of the mainline churches of Protestantism. The historical underpinnings of those doctrines had faced increasing skepticism. Rauschenbusch was not immune to this. He dismissed the notion of Christ’s death as an atonement for sin, seeing in it, rather, an example of suffering love whose power was to be found in its ability to encourage people to act in the same way.

He described six sins which Jesus “bore” on the Cross:

Religious bigotry, the combination of graft and political power, the corruption of justice, the mob spirit and mob action, militarism, and class contempt – every student of history will recognize that these sum up constitutional forces in the Kingdom of Evil. Jesus bore these sins in no legal or artificial sense, but in their impact on his own body and soul. He had not contributed to them, as we have, and yet they were laid on him. They were not only the sins of Caiaphas, Pilate, or Judas, but the social sin of all mankind, to which all who ever lived have contributed, and under which all who ever lived have suffered.

These “powers of evil” were embodied in social institutions. The work of the Kingdom of God consisted in resisting these institutions and reforming society.

Liberal Christianity adopted Rauschenbusch’s vision in a wide variety of ways. That his vision was largely political should be noted. Interestingly, he saw the Church as a problematic institution and preferred to speak, instead, of the “Kingdom of God,” by which he meant the political project opposed to the six sins.

It is, of course, an interesting approach to the faith and has been a well-spring for many of the Christian social movements of the past century. It is also a jettisoning of the ontological and spiritual content of the faith traditionally associated with classical Christianity (such as Orthodoxy). It is also the form of Christianity favored by the cultural elite of our time. It needs none of the messiness of doctrine, only the clarity of moral teaching. Indeed, it would be possible to practice such a Christianity believing Jesus to be merely human.

Another aspect of the modern social gospel (endemic, I think, to its so-called “demythologized” approach to the Scriptures) is its adherence to Utilitarianism as a moral principle. That principle is a results-oriented philosophy, described best as a moral model in which all efforts are managed towards a desired end. It presumes the control of outcomes.

None of this needs a God, nor a Savior. As such, it is ideally suited to a secularized Christianity. In large part, it provides a Christian slogan for otherwise secular ends. In Rauschenbusch’s time, the place of the institutional Church was strong, almost unassailable. Over time, the secularization of the Church, married to his vision of the gospel, has resulted in the death of the very institutions that gave it birth.

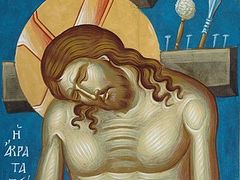

The rhetoric of “building the Kingdom,” made popular by Rauschenbusch, is a deep distortion of the phrase, despite its best intentions. Christ is far more than a good man who set an example, and more than a victim of social wrong-doing. The Christian story is far richer. The nature of sin is death, not mere social oppression. Death reigns over us and holds us in bondage to its movement away from God. It certainly manifests itself in various forms of evil-doing. But it also has a cosmic sway in the movement of all things towards death, destruction, and decay. Our problem is not our morality: it is ontological, rooted in our alienation from being, truth, and beauty – from God Himself. Broken communion leads to death. Immorality, in all its forms, is but a symptom.

However, God, in His mercy, entered into the fullness of our condition, our humanity, taking our brokenness on Himself:

Inasmuch then as the children have partaken of flesh and blood, He Himself likewise shared in the same, that through death He might destroy him who had the power of death, that is, the devil, and release those who through fear of death were all their lifetime subject to bondage. Hebrew 2:14-15

This is not the language of Christ as exemplar – it is Christ as atoning and deifying God/Man and Savior. The Kingdom of God as improvement, regardless of how well intended and managed, is still nothing more than a world of the walking dead. The Kingdom of God, as preached by Christ, is nothing less than resurrection from the dead.

We have been nurtured in a couple of centuries of Utilitarian rhetoric and thought. Nothing seems more normal to us than setting goals, making plans, and achieving results. It is not surprising that we might imagine God working in a similar manner. This is not the case.

Consider the story of the Patriarch Joseph. Betrayed by his brothers, sold into slavery, falsely accused by his master’s wife, thrown into prison, where he meets other prisoners and interprets dreams, thus coming to the attention of the Pharoah, whose dream he interprets and offers wise counsel, whereby he is made Regent over Egypt, saving his family from famine.

What people in their right mind would ever consider such a plan as a means to reach the goal of saving themselves from a famine they had no idea was coming? No one. Indeed, event after event in the story appear to be nothing but ongoing tragedies. Joseph himself would later say of these things: “You [my brothers] meant it to me for evil, but the Lord meant it to me for good.”

That is the inscrutable nature of providence – as illustrated repeatedly in the Scriptures. The mystery of God’s providence, the working of the Kingdom of God in our midst, is inscrutable.

“He has exalted the humble and meek and the rich He has sent away empty.”

In these latter days, the masters of machines and money have imagined themselves to be “building the Kingdom” (Blake’s Jerusalem) with plans, intentions, goals, and utopias. [Such language was the bread and butter of public speech in my time among the Episcopalians]. The plans generally seemed to involve the rich helping the humble and meek so they would no longer need to be humble and meek. With every success they became even greater strangers to God. Their Churches stand empty, their children having forgotten God and looked towards other dreams.

It is the nature of the humble and meek to be clueless about the management of worldly affairs. They are generally excluded from management decisions. It is instructive in this regard to consider the nature of Christ’s commandments: they tend to be small and direct. Give. Love. Forgive. Take no thought for tomorrow. Endure insults.

As is true in the story of Joseph, the work of providence is largely seen only in retrospect. Its daily work in our lives will, more often than not, find us unjustly imprisoned by the lies of a wicked employer, or nailed to a Cross while being mocked. St. Paul describes the providence of God:

“For I think that God has displayed us, the apostles, last, as men condemned to death; for we have been made a spectacle to the world, both to angels and to men.We are fools for Christ’s sake, but you are wise in Christ! We are weak, but you are strong! You are distinguished, but we are dishonored!To the present hour we both hunger and thirst, and we are poorly clothed, and beaten, and homeless.And we labor, working with our own hands. Being reviled, we bless; being persecuted, we endure; being defamed, we entreat. We have been made as the filth of the world, the offscouring of all things until now.” (1 Corinthians 4:9–13)

If we are to speak of “building up the Kingdom of God,” let it be restricted to that work within us of “acquiring the Holy Spirit.” And then, speak with humility. Again, St. Paul says this about such things:

“For I know of nothing against myself, yet I am not justified by this; but He who judges me is the Lord. Therefore judge nothing before the time, until the Lord comes, who will both bring to light the hidden things of darkness and reveal the counsels of the hearts. Then each one’s praise will come from God.”(1 Corinthians 4:4–5)

Our hearts long for “Jerusalem,” indeed. But the city we long for is not the project of William Blake’s dreams. It is ironic that Blake lived in a culture that had intentionally destroyed all of its monasteries, murdering many of its monks. And then it wondered where Jerusalem had gone.