I can honestly tell you that I feel very bad when You are not around. There’s bread on the table, a friend here who has come to visit, and we have some freshly-brewed beer, too. A dry log is crackling in the fireplace, my youngest daughter is playing on the floor, and my sons are painting sailing boats with their water-colours. It is snowing softly outside my window. For goodness’ sake, what else can a man want for happiness? But, frankly, I can tell you that it feels sad when You are not around!

Have You ever seen the eyes of a pet dog? One who is well-fed, clean and loved by all? Of course, You have. You’ve seen everything. How sad those eyes are! Very intelligent but very sad. Such are the eyes of a smart person who’s got it all and who is loved by all but who does not feel Your presence by his side.

I’ve always known that You exist. It’s not even a belief. It’s a conviction, a certain kind of knowledge. Is it even possible for You not to exist? Still, it’s not enough for me to know that You exist. I want to feel You next to my bosom, like a warm sheepskin coat. I want to hear Your voice and to smell Your smell.

I went to the outskirts of town on many occasions and shouted, cried, prayed. (I know You remember that.) I asked You to come, to draw near, to enable me to feel your presence. You kept silent. You know how to be silent like no other. And I would return home deafened by my own screams, tired and fed up with my cries. Nothing came of my petitions, but then strange events, one after another, started to bother and disturb my weary, sleepy soul.

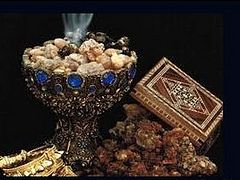

To begin with, on a typical winter day, three unusual-looking horsemen rode past our window. They wore tall hats of a strange style. In their frozen hands each of them held a little box. The muzzles of their horses were covered with frost, which indicated that these animals were used to a milder climate. I opened a window, and one of the riders whose face was concealed beneath a bushy beard turned towards me and said, quietly but distinctly, in Farsi: “U omad”, which means “He has come”.

They rode on. I followed them for a long time with my gaze, as all the while the snowy wind lashed my face. Who has come? Who were these strange men telling me about? How do they know that I understand a bit of Farsi?

“Do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself” (Mt 6.34). No, I did not forget about the three horsemen, whose tracks were quickly covered by a new blanket of snow. I decided to put this thought to the back of my mind and got busy with household chores. Several days passed like this. However, the surprise that I had experienced earlier returned once again, when in my own house those same words were spoken in my own language, not a foreign one.

Some old shepherds—the type who are good-natured, merry and full of good-hearted humour, always ready to laugh at themselves when we make fun of them—brought a new element of surprise into my home. We often laugh at their impoverished lives, their funny clothes and their flocks, which they love more than their own wives. They pay us back with the same token, however, calling us stick-in-the-muds or bedbugs who skulk behind the stove. They say they would not swap their piece of cheese and gulp of wine for all the delicacies in the world. Some of them even dare to predict that this simple shepherd’s meal of rusks with cheese and wine will eventually embellish the tables of the rich.

On this occasion, a certain manner of fright came over them. Their weather-beaten faces revealed a child-like alarm and genuine amazement.

“We remember,” they said, “that a shepherd once became king of Israel. We know that he was loved by God and protected by the angels. But as honest shepherds we give our honest word that we never ever thought that angels would appear to us!”

“Tell me exactly what happened,” I said, handing them each a cup of grog.

They told me how, as they were tending their flocks as usual, angels suddenly started to sing above their heads, making them almost die of fright. They said that the main point of the angels’ song was the birth of someone who would bring peace on earth, and in people’s hearts a striving for kindness.

We had one more glass of that strong, hot drink and then I asked them to tell me in more detail about what they had seen. Alas! These shepherds, I tell you… Have you ever had a conversation with shepherds? Have you ever drunk grog with them? Having got themselves tipsy, they quickly forgot all about the topic of our conversation and started to nod off. Those who work outside fall asleep quickly in the warmth.

Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni di Consolo). The Journey of the Magi

Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni di Consolo). The Journey of the Magi

They fell asleep, and I left the house. I knew where they usually went with their flocks and also where the event described by those horsemen with weather-beaten faces could have taken place. The hard, dry snow made a crunching noise beneath my feet, as I walked towards the shepherds’ pastures. Suddenly I felt an unusual, warm, soft light on my cheeks. It did not blind me, but it did warm my cheeks. The God to whom I had prayed so much before knows that it was beyond human strength to resist walking towards that light. I carried on and eventually noticed foot prints in the snow; I realised that I was not the first person to have followed this path.

I don’t remember exactly who was there besides me, and don’t want to get things wrong. They might have been old people or young people. Anyway, I passed through a small crowd, not recognising or even noticing anyone. The door creaked, and instantly I began to squint. No, it wasn’t because of the bright light. No. The lighting in the house was very poor indeed. Why I narrowed my eyes was because of the radiance that surrounded that Baby’s head, as it slept peacefully in its Mother’s arms. He looked like a simple, ordinary child. Just like a child who might cry when it has wind, or who would search for his mother’s nipple when hungry, and would go red in the face when about to cry. But I am no simpleton, am I? I do understand that no ox would breathe warm air through its nostrils to keep a Baby warm, if that Baby were not special. No stranger would travel such long distances to see any ordinary child. No shepherd, no matter how drunk, would invent improbable stories, alluding in his fantasies to God Himself. And what about that halo round His head? Did it not make clear, better than any words could, who had come and who had been born?

I stood still in a corner of the room, too scared to move lest I make the floorboards squeak. My eyes were focussed on the soft, warm depths of the glowing cradle and my thoughts began to race like mad.

“Is this really You?” I thought. “Have You really come? So strangely and unexpectedly? So helpless and weak, so tender and defenceless? When I previously begged You to come, I thought it had taken all my strength. But now that You are here, I feel even more exhausted than ever. Because You came so unexpectedly and without all that splendour…”

I stood and watched. Words were intertwining into chains and threads, and then unwinding again, leaving my thoughts empty and helpless. I had been expecting one thing but received another. I had encountered something I had never dreamt about. It was time to stop thinking. My knees bent by themselves, and I bowed down, touching the floor with my forehead. “You did the right thing,” I heard in my right ear after a minute. “There’s no need to ponder. You need to worship!”

I turned and saw a shining vision, just for a second. Perhaps it was one of those angels that had announced to the shepherds the birth of Our Lord from the Virgin. How well they speak! How concisely and precisely do angels talk! There’s no need to ponder over it. What you need to do is worship!

So I worshipped Him, and then got off my knees and stood up straight. The little Baby was still asleep. His Mother bent down towards Him and sang, quietly and softly. Not daring to turn my back on them, moving backwards, I went back outside, taking with me such an intense mixture of feelings that I could easily have imbued a thousand passers-by, and even sated them, with all the sweetness I felt at that moment.

The dry, hard snow crunched beneath my feet. It fell onto my eyelashes, sticking to my moustache and beard, and melting on the warm skin of my neck. “He came,” I thought, choking on streaming tears. “He came, though not how I had asked. But in His own way—humbly, in an unimaginable manner. How good He is! How …”

When I returned home, the shepherds had just begun to wake up. “Well,” they asked, “have you been to see Him?”

I kept silent. The snow on my eyelashes had melted, but the shepherds knew how to tell real tears from ordinary melted snow on the face. They could also tell the difference between tears of reverence and tears of hurt and resentment.

“Let’s have a drink!” said one of them. The sound of his voice rescued us from the silence that was hanging over us. We drank and sang for a long time, rejoicing until dawn. We were scared to utter any needless, unnecessary words, lest the rough sounds of human conversation should insult the mystery which had touched us all.

So He did come then! How interesting human life will be from now on! How complex and intricate! How strangely but happily will people now live!

I was happy beyond all measure. Neither the abundance of mulled wine nor the noise of the shepherds’ company prevented me from saying to myself over and over in the midst of this spontaneous feast, “You came! You really came! Thank You!”