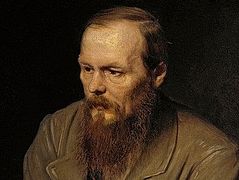

Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. Portrait by Vasili Perov, 1872. Photo: wikimedia.org

Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. Portrait by Vasili Perov, 1872. Photo: wikimedia.org

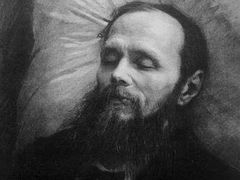

One reason it’s time to read or reread the immortal Dostoevsky is that 2021 is the “Year of Dostoevsky”. Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, the matchless Russian writer of the nineteenth century, was born on October 30 / November 11, 1821—which makes this year the 200th anniversary of his birth. And today is the 140th anniversary of his death.1

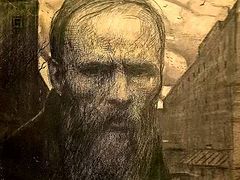

Dostoevsky as a military engineer. Photo: wikimedia.org We owe a great deal to Dostoevsky. It has often been considered that no other author has brought so many modern heterodox to Orthodoxy. Why this is true could be the subject of volumes. Even so, very little has been published specifically about Dostoevsky and the Orthodox Church. Perhaps this is because Dostoevsky was not a religious figure by any reckoning. He was a religious searcher who found his soul’s desire in Jesus Christ, in His true Church; and because he was such an abundantly gifted writer, and because his writing could not be separated in any way from his own deep convictions, his books lead us in a mysterious way to those deep convictions. That is why, even if you have read his books at some time in your life, such as in literature classes or in your youth, you will not find it unrewarding reread them again and again.

Dostoevsky as a military engineer. Photo: wikimedia.org We owe a great deal to Dostoevsky. It has often been considered that no other author has brought so many modern heterodox to Orthodoxy. Why this is true could be the subject of volumes. Even so, very little has been published specifically about Dostoevsky and the Orthodox Church. Perhaps this is because Dostoevsky was not a religious figure by any reckoning. He was a religious searcher who found his soul’s desire in Jesus Christ, in His true Church; and because he was such an abundantly gifted writer, and because his writing could not be separated in any way from his own deep convictions, his books lead us in a mysterious way to those deep convictions. That is why, even if you have read his books at some time in your life, such as in literature classes or in your youth, you will not find it unrewarding reread them again and again.

It has been said that “God is in the details”. It has also been said that “the devil is in the details”. I think that both sayings are correct, and that is why Dostoevsky should be reread. The details of all his characters, their mannerisms, their actions, their thoughts and words, even their names, all paint individual pictures of the human condition in relation to God and the devil—pictures that don’t fade with time, and are applicable in any culture. How clearly we can learn about the battle between good and evil—which in Dostoevsky’s words, takes place in the human heart—by carefully reading his novels!

It’s always tempting to think that world-famous authors whose content is deeply religious and humane had flawless lives marked by milestones of one success after another. Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky’s life, quite to the contrary, was turbulent and full of contradictions and failures. Although his father came from an ancient line of noblemen in Belorussia, he became a medical doctor in St. Petersburg, and the family was raised in on grounds of his father’s hospital in a lower-class neighborhood. As a boy, Feodor Mikhailovich was, in his parents’ words, hot-headed, stubborn, and cheeky; as a youth he was morose, introverted, and unsociable. At the same time, he was raised in a deeply religious environment, felt profound compassion for the sick and poor even at a tender age, and as a student he was known to defend newcomers and teachers from rougher classmates.

The Parents - Mikhail Andreyevich and Maria Fyodorovna Dostoevsky. Photo: wikimedia.org

The Parents - Mikhail Andreyevich and Maria Fyodorovna Dostoevsky. Photo: wikimedia.org

At night his parents read him Russian and Western literature, including Gothic and Romantic, but he learned to read and write using only the New Testament. He disliked hard sciences and math, but his writings would not have been as perfectly crafted without these courses so indispensable to his military engineering education.

Staged execution on Semonov Square. Photo: wikimedia.org

Staged execution on Semonov Square. Photo: wikimedia.org

Once he was freed from his military career and began to devote himself more to literature, his first works—literary translations—were unsuccessful. His compassion for humanity led him to socialist circles, which, as he would eventually understand, were in fact seething with anti-humanity. These attempts at social reform would also end in failure for him, and he nearly lost his life in front of a firing squad. His sentence was commuted at the last minute, and he was sent to Siberia for prison and then exile. In prison he was respected by all, but at the same time considered a dangerous revolutionary and kept in shackles and manacles for his entire sentence.

Anna Grigorevna Dostoevskaya (Snitkina). Photo: wikimedia.org His personal life was also full of contradictions. In exile he fell in love with a married woman, and married her after she became a widow, but his marriage was unhappy and tumultuous. His wife died of tuberculosis, but he would only know the joy and peace of a happy marriage after all his financial failures forced him to hire a secretary. This secretary became his second wife, who although not rich herself had to sell all her valuables to pay off his debts. She would soon have to endure a period when they were always on the brink of penury due to his gambling addiction. But after his death, his devoted Anna Grigorevna would write her own biography of her husband that exudes love and admiration from every page—without passing over the genius’s obvious weaknesses. She called him the “most chaste of men”, and a picture of him emerges as a combination of selflessness, compassion, and heart bottomless in its ability to love.

Anna Grigorevna Dostoevskaya (Snitkina). Photo: wikimedia.org His personal life was also full of contradictions. In exile he fell in love with a married woman, and married her after she became a widow, but his marriage was unhappy and tumultuous. His wife died of tuberculosis, but he would only know the joy and peace of a happy marriage after all his financial failures forced him to hire a secretary. This secretary became his second wife, who although not rich herself had to sell all her valuables to pay off his debts. She would soon have to endure a period when they were always on the brink of penury due to his gambling addiction. But after his death, his devoted Anna Grigorevna would write her own biography of her husband that exudes love and admiration from every page—without passing over the genius’s obvious weaknesses. She called him the “most chaste of men”, and a picture of him emerges as a combination of selflessness, compassion, and heart bottomless in its ability to love.

It is the combination of falls and risings, addictions later overcome, compassion for sinful mankind but intolerance of falsehood, terrible sorrows and supreme joys, rare genius and humble sensitivity, and most importantly, his deeply Orthodox Christian soul that brought us the great Dostoevsky. But neither can we forget that an underlying quality present in him from childhood was also key to producing the literary heritage that we have today: stubbornness. Through all his failures—and apparently, he took critical failure very hard as his epileptic fits were brought on by them—he never gave up his calling and forged ahead with novels that change people’s lives.

Let’s read them all if we can. And then let’s reread them. This is the year to do it.