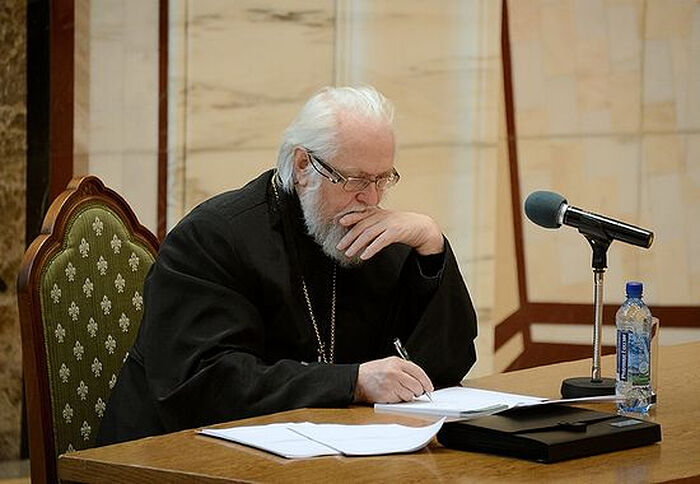

Archpriest Vladislav Tsypin, Deputy Chairman of the Moscow Diocesan Court, commented on the court’s decision in the case of Protodeacon Andrei Kurayev, who was banned from serving as a cleric of the Moscow City Diocese.

This interview also sheds light on the process of an ecclesiastical court in general.

—Father Vladislav, today there was a meeting of the Diocesan Court of Moscow on the appeal of Protodeacon Andrei Kuryaev. In connection with this case, public attention was again drawn to this church institution. The first question is what is the ecclesiastical court, what is its purpose and main task?

—The “Statute on the Church Court” says that “Church courts are designed to restore the broken order and structure of church life and are called to promote the observance of the sacred canons and other ordinances of the Orthodox Church.” We can add to this that the task of the court, in addition to establishing the truth in the case, is to exhort the guilty cleric in the hope of his repentance and correction. Obviously, it is easier for a person to rethink his behavior if he is not in the lens of cameras and the attention of journalists, who will not miss the opportunity to make a sensation out of this.

The ecclesiastical court is, in fact, a disciplinary collegium under the ruling bishop, who alone has full judicial power; he delegates part of his judicial powers to the diocesan court at his discretion. The church court has several tasks.

First of all—it is necessary to establish the fact of the ecclesiastical offense and its nature. Then—to find out whether the accused is guilty or not in cases where this guilt is not obvious (and sometimes it is obvious ... for example, when a cleric entered into a second marriage). Further—if the cleric is guilty, determine whether there is a reason for church “economy”, that is, the application of punishments provided for by the canons and other church legal acts not in the fullness of their severity. Finally, to determine what punishment the cleric is subject to for his actions. This is all the more necessary since not everything that a cleric can do today is provided for by the canons. For example, drug addiction—although it is extremely rare among the clergy, it happens ... It is obvious that the compilers of the canons did not encounter this misfortune of our time. In such cases, decisions can be made that have the character of a judicial precedent.

Having discussed all this, the court makes a decision, which is essentially a recommendation to the diocesan bishop—what must be done for the benefit of the Church and the spiritual benefit of the cleric whose case is being considered. After all, church punishments themselves have, in contrast to the secular system of criminal law, a completely different nature and a different goal.

—Which goal?

—The purpose of church discipline is to promote the eternal salvation of people. In particular, by the severity of punishment to help them realize the harmfulness of their path. In addition, in the event of defrocking, the goal is, firstly, to protect other members of the Church from an unworthy clergyman, and, secondly, to exclude the combination of priesthood and behavior unacceptable for a clergyman, which is harmful for the former cleric himself.

—Are there any other differences between secular and ecclesiastical courts?

—Both secular and ecclesiastical courts are called to establish the truth in the case, in this sense, both of them set the goal of restoring justice. It should be noted that the secularization of the state led to secularization and judicial proceedings. In ancient times, for example, any court was considered a sacred rite, now formal procedures dominate in a secular court. They are designed to minimize the factor of “unjust trial”, the desire of the accused to avoid punishment, the lawyer to earn money and other human factors that are inherent in the participants in the trial. Whether this made the court more perfect is a question. However, it cannot be said that secular justice has completely lost its religious dimension; references to the immaterial remain in it. For example, the institution of the oath of a judge in Russia and other countries is undoubtedly a relic of a sacred attitude towards justice. In some European countries, they still swear on the Bible in court.

The ecclesiastical court continues to be built on the full responsibility of the bishop for the clergy and flock of his diocese before God. In general, we can say that legal procedures are secondary in the scope of the church court, which, however, does not mean that they are unnecessary. The Church regards the bishop as the bearer of all hierarchical power in his diocese and entrusts him, in particular, with the fullness of the judicial power. It is the bishop who pronounces the verdict, assessing the actions of the clergyman and the measure of punishment for them.

As I have already mentioned, at present in dioceses, in order to establish the guilt of a clergyman, the motives of his misdeeds, to study possible extenuating circumstances, there are collegiums, which are called diocesan courts. They are composed of five persons in the priesthood. However, they do not have the right to make a final decision, since, as emphasized in the Regulations on the Church Court: “The judicial power exercised in this case by the diocesan court derives from the canonical authority of the diocesan bishop, which the diocesan bishop delegates to the diocesan court” (Article 3.2). Therefore, the diocesan court is not in the full sense a court from the point of view of secular law, and the decision of this collegium of presbyters is not, in fact, a “sentence” in the strict sense of the word. In this decision, in addition to describing the essence of the case and the canonical assessment of the clergyman’s misconduct, a “recommendation of what is possible from the point of view of the ecclesiastical court of canonical interdiction (punishment) if it is necessary to bring the accused person to canonical responsibility “(Article 46.1). Thus, this is a kind of a recommendation jointly worked out by a group of pastors, on the basis of which the diocesan bishop has the opportunity to make his final decision.

Let me remind you that at the beginning of the twentieth century, there were lengthy discussions on the topic of whether the ecclesiastical court should receive the mechanisms that at that time were widespread and recognized in state legal proceedings. Proposals on this issue were submitted for consideration by the Local Council of 1917–1918, and the Council voted for this project. But then—and this is the only time in the annual history of the meetings of the Council—the bishops who participated in the Council and composed the Bishops’ Conference at it, who were otherwise more than loyal to the most “advanced” proposals in the field of church administration (for example, the participation of the laity in the election of bishops), vetoed this bill, since its implementation would mean a deviation from the very canonical foundations of the Church’s existence.

In different historical periods, the dividing line between secular and ecclesiastical courts passed in different ways. There were times, for example, when in the Russian Empire all marriage and family matters were within the jurisdiction of church courts. In both Europe and Russia, the bishop’s authority in church estates included the right to court in cases that we would now call civil and criminal.

Currently, due to the secularization of the state, one of the main differences between ecclesiastical and state courts is that the sanctions of ecclesiastical courts do not in the least affect the civil status and civil rights of the persons to whom they are applied, and these sanctions themselves cannot be coercive.

—And what does the closed nature of the church trial mean? Why is this needed?

—The closed nature of the trial is not something incredible even for a secular trial. The judicial system of almost any state provides for such a possibility... This concerns the secrets of personal life, state secrets and other issues. Thus, the public nature of judicial proceedings is not an absolute rule, even for secular courts.

If we draw a conditional analogy, then the form of the church court should be compared, rather, with an official audit in an organization, which is almost always closed. After all, it applies to relations that arise only in connection with the voluntary occupation of a position by a person in a particular organization and his consent to such a check. The alternative always exists: to sever ties with this organization and not participate in any checks. There is no such opportunity for a secular state court, civil or criminal. One cannot simply “refuse” participation in it without negative consequences for oneself. The strictest decision that an ecclesiastical court can make is to state that there is no connection between the defendant and the Church.

The closed nature of ecclesiastical legal proceedings is also due to the fact that in most cases, although not in all, the court considers the actions of both a clergyman and other persons related to private life, which much less often becomes the subject of consideration in a secular court. For example, adultery is not punishable according to the norms of secular law, but it is an offense from the point of view of canon law.

—Do prosecutors and lawyers participate in the church trial?

—The parties to the prosecution and defense in a secular court are engaged in the procedurally difficult task of proving the guilt of the defendant. In an ecclesiastical court, if we compare it with an internal audit procedure, competition between the participants in the process is not expected. Church judges and the defendant are not parties to the discussion or dispute.

If we take the case of Protodeacon Andrei Kuraev, then even from the point of view of secular law, all of his behavior can be qualified at least as unethical, not to mention compliance with the Gospel commandments and those rules and norms of behavior and attitude towards neighbors that a Christian must adhere to and a cleric of the Orthodox Church. By the way, Archpriest Georgy Breyev, who died last year and had a high spiritual authority among Muscovites and whose spiritual child Fr Andrei positioned himself to be from the very beginning of his church ministry, spoke about this publicly, with humility and love, to Kurayev at one time.

All of his abusive and insulting words addressed to his fellows, church institutions and the Church itself were of a public nature, and they do not require special evidence for the purposes of the church court. Now he is trying, referring to the concept of libel in criminal law, to determine whether the church court has proven his guilt of libel or not. But the ecclesiastical court does not have the obligation to prove libel in the order in which it is accepted in the criminal court, because it does not impose a comparable punishment related to the civil rights of the defendant, possible restriction of his freedom or material losses, but only states unethical behavior, which is expressed in the reckless, if not malicious, dissemination of unverified scandalous information.

But if one of the people about whom Kuraev is spreading information discrediting their honor goes to a civil court, then he himself will have to prove that his accusations are true.

Continuing with the in-house audit analogy, it is obvious that a person who wants to stay in touch with their organization will voluntarily take part in such a review. Fr Andrei has recently spoken a lot about his role as a kind of “resuscitator-reanimator” of the Church, about the benefits that his activities allegedly bring.

It seems that everything is clear—you have been summoned to the court and are ready to hear what the case has become? However, Kurayev did not appear at the hearing, citing poor health, Moscow traffic jams, a pandemic, which caused the court hearings to be postponed four times. At the same time, we had the opportunity to observe how Fr Andrei flirted with the readers of his blog, asking them whether to go to court or not. By the way, after one of the invitations to the court, he intimately asked the court clerk where the session would take place, how to get to the courtroom. This is quite convincing evidence, albeit extremely sad, that Fr Andrei was initially interested not so much in establishing the truth, preserving the holy dignity, but in attracting as much media attention to himself as possible. Actually, all his recent activities, although portrayed by him as helping the Church in overcoming her problems, boils down to attracting such attention...

—Kuryaev has repeatedly referred to the injustice of not being given time to prepare his “defense”. But, if the person summoned to the meeting of the church court asks for time to prepare his answers, put by the court, can the consideration of his case be postponed?

—I also read his statement that he would not know even at the trial what he was accused of, since he was not allowed to bring a computer with him. The court had at its disposal a printout of all of his statements, which were then recorded in the court’s decision in the form of links to Internet pages. These printouts are still in the court case. And, of course, all these texts would have been shown to Kurayev if he had arrived at the meeting. As for the order of the court’s actions, Fr Andrei himself admitted in his reply to the chairman of the court to the first summons that the diocesan court acted in full accordance with the Regulations on the Church Court. He did not like the situation itself. One way or another, Kurayev filed a petition for a reconsideration of the case, already having the opportunity to fully examine the verdict that was transmitted to him and published. He published all objections in the public arena before being considered by the court, which indicates that he addresses them, first of all, again not to the court, but to journalists and subscribers of his blog.

As for the question of principle—whether the participant in the proceedings can be given time to prepare well-founded facts to answer the judges’ questions—of course, such time can be given.

—How would you comment on today’s decision of the Church Court in the Kurayev case?

—Protodeacon Andrei Kuraev accompanies his petition for reconsideration with a report in which he sets out the formal reasons why, in his opinion, his case should be admitted for reconsideration, as well as a long note in which he writes why, in his opinion, the court’s decision must be changed. All this was published by him.

As for the formal reasons for the revision, listed by Kuraev, some of them are completely untenable, others, perhaps, are a reason for discussion, but not within the framework of the current Regulation on the Church Court.

The “debatable” claim concerns the procedure for familiarizing the accused with the case materials. This has already been discussed above. One way or another, as I have already mentioned, Kurayev previously admitted that in this matter the diocesan court acted in accordance with the Regulations on the Church Court.

For example, Kurayev’s claim that his case was investigated for more than one month is untenable. Kurayev quotes the following article of the Regulations on the Court: “The decision of the diocesan court on the case must be made no later than one month from the date the diocesan bishop issues an order to transfer the case to the diocesan court.” But the fact is that this article has a continuation: “If a more thorough investigation of the case is necessary, the diocesan bishop may extend this period at the reasoned request of the chairman of the diocesan court.” It was within the framework of this clause that the ecclesiastical court acted.

Or another example: Kurayev makes a claim that he was not familiarized with the names of the applicants in his case. But according to the Regulation, a church court case can be initiated without the presence of applicants, on the basis of “a report of a committed church offense received from other sources.” That is, a bishop who has learned from open or closed sources about a possible violation by the cleric has the right to send this information to the church court.

The appeal of Protodeacon Andrei Kurayev is full of such omissions and reservations.

As for the substantive objections, it is especially strange to read that Kurayev considers himself entitled to call the Church a harlot (he uses an obscene word). Nobody cancelled administrative responsibility for swearing in public places, and if we are talking about the use of this word in relation to the Church, then we can talk about “insulting the feelings of believers.” And in general, outside of any legal logic: how can a person remain in the holy dignity, who in this way names the religious community in which he was baptized and ordained?

Or, for example, Kurayev did not understand why he was accused of spreading rumours that cast a shadow on the reputation of the bishops. It seems to Fr Andrei that various disgusting rumours, not supported by anything meaningful, can be publicly disseminated with impunity, and then let the accused vindicate themselves. But Kurayev cannot but understand that the aftertaste will remain in any case... Moreover, even in the case of the former Bishop Flavian, who was defrocked at the end of December (and, by the way, how does Kurayev know that it was exactly on that charge which he had raised against him?)—the court, unlike Kurayev, operated not with rumours and gossip, but with facts and evidence. For this, there is a church court, a church investigation, so that people do not suffer from false accusations. And this, by the way, is another reason why church courts are closed.

In general, following the consideration of the appeal of Protodeacon Andrei Kurayev, the diocesan court, having asked him some clarifying questions, came to the conclusion that there were no reasons for changing the previous decision. This decision was handed to him, published and submitted for approval to His Holiness the Patriarch as the diocesan bishop of the city of Moscow, of which Kuraev is a member. However, given that the Patriarch is at the same time the person to whom a person convicted by a diocesan court can appeal to the Supreme Church-wide Court, I believe that the issue of approving our decision will be relevant after the ten-day period for filing an appeal established by the Court Regulations expires. from the date of delivery of the decision of the diocesan court to the defendant.