This story by author Boris Shiryaev (1889–1959; emigrated to Italy in 1945) was taken from the collection of Paschal stories, “The Mystery of the Resurrection”, published by The Free Wanderer publishing house of the Pskov Caves Monastery.

Dedicated to the blessed memory of artist Mikhail Vasilyevich Nesterov, who told me on the day he received his verdict: “Don’t be afraid of the Solovki. Christ is close there.”

When the first breath of spring breaks up the covering ice, the White Sea is frightening. Breaking away from the hardened ice, ice-floes rush northwards as if in drunken joy, colliding and breaking up with a tremendous cracking noise, climbing on top of each other, piling into “hills” and crumbling up again. Only a rare helmsman will dare take a karbass [a wooden boat with two sails and three to ten oars.—Trans.]—an unwieldy yet strong Pomor wooden longboat—out to sea, save in extreme need. But no one will set off from the shore when the seemingly calm sea is covered with a gray mass of sludge—actually fine, dense ice. There is no escape from it! It grips the longboat firmly with its whitish paws and carries it to midnight, from whence there is no return.

On a dusky, foggy April day a handful of people were standing at an inconvenient moment on the jetty near the former St. Sabbatius’ Skete—now the arena of a group of fishermen consisting of the remaining Solovki Monastery brethren and convicts. There were monks, security officers, and fishermen from among convicts, and most of them were clerics. All were peering continually into the distance. The ice mass was creeping along the sea, cracking ominously.

“Their lives will be lost, they will perish,” said an old monk in a torn overcoat, pointing to a barely noticeable dot flickering in the icy haze. “You can’t get away from the sludge.”

“God is in control.”

“How did they get there?”

“Who knows? There are strong currents there, the sea is clear; so they went out, the fools, but the water seized them and drew them into the ice mass. It has swallowed them up and it won’t release them. It’s not the first time this has happened.”

Konev, the head of the Cheka1 post, tore the Zeiss binoculars from his eyes.

“There are four of them in the boat. Two rowers and two in uniform. Sukhov must be among them.”

“It must be him. He’s a brave hunter and avid for prey. Now the beluga white whales are running. They may weigh as much as 3,600 pounds. Everyone is proud of catching such a monster. So he’s taken a chance!”

“So you say they can’t escape?” The Cheka officer asked the monk.

“There has never been a time when someone came out of the icy mass on a longboat.”

Most of those standing made the sign of the cross. Someone whispered a prayer. And there, in the distance, a black dot flickered, now hiding in the ice, now reappearing for an instant. There was a desperate struggle between a group of men and the evil, cunning element, which was still overpowering them.

“Yes, you can’t get even away from the shore in such slush, let alone get away from the mass of ice,” said the Cheka officer, wiping the binocular lenses with a handkerchief. “It’s all up with Sukhov! Write off the regimental military commissar!”

“Well, as God wills,” a quiet voice, full of deep, inner strength, was heard.

Holy Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky) Everybody involuntarily turned to look at a short, stout fisherman with a gray, broad and thick beard.

Holy Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky) Everybody involuntarily turned to look at a short, stout fisherman with a gray, broad and thick beard.

“Who is going to join me for the glory of God, for the salvation of human souls?” the fisherman continued just as quietly and confidently, looking around the crowd and peering into everyone’s eyes. “You, Fr. Spyridon, you, Fr. Tikhon, and these two Solovki men... And it’ll be fine. Drag the karbass to the sea!”

“I won’t allow it!” the Cheka officer suddenly exploded. “Without the guards and permission of the administration I won’t let you out into the sea!”

“The administration is out there struggling with the ice; and we don’t refuse the guards. Get on the boat, comrade Konev!”

The Cheka officer shrank at once, went limp and walked away from the shore silently.

“Ready?”

“The longboat is on the water, Vladyka!”

“God be with you!”

Vladyka Hilarion stood at the helm, and the boat departed from the shore, slowly making its way through the frozen ice.

Dusk fell. It was followed by a cold, windy Solovki night, but no one left the jetty. Something unanimous and great welded these people together—everyone without distinction, even the Cheka officer with his binoculars. They spoke in a whisper and prayed to God in a whisper. They believed and doubted. Doubted and believed.

“Nobody is like God!”

“Without His will the ice won’t let go of them.”

They listened to the nocturnal sound of the sea attentively, their eyes boring through the darkness hanging over it. Still whispering, still praying.

But it was not until the sun dispersed the wall of fog that they saw the boat returning with nine—not four—people on it.

And then everyone on the jetty—the monks, the convicts, the guards—everybody without distinction made the sign of the cross and knelt down.

“A true miracle! The Lord has saved them!”

“God has saved them!” said Vladyka Hilarion, pulling the exhausted Sukhov out of the longboat.

That year Pascha was late, in May, when the cool northern sun had already hung in the gray, pale sky for a long time. Spring set in; I was then at hard labor at the disposal of the Military Commissar of the Special Solovki Regiment—Sukhov. Once, when the buds of the thin Solovki birches were quietly and sweetly fragrant, I was walking with him past the crucifix into which he had fired two shots. Drops of spring rains and melting snow were accumulating in the wounds—the depressions from the buckshot—and flowing down in dark streams. The chest of the Crucified One was bleeding. Suddenly, unexpectedly for me, Sukhov pulled off his “budyonovka” pointed cloth helmet, stopped and—hastily and sweepingly—made the sign of the cross.

“Don’t say a word to anyone or I’ll leave you to rot in the punishment cell! What day is it today? Do you know? Holy Saturday…”

The image of the Crucified Christ (the Russian, “homespun” One, Who looked like a slave and seemed to have walked all over His land and our land, shot by a murderer who now bowed to Him) vaguely paled in the advancing whitish twilight.

It seemed to me that the light of an unearthly smile flickered on Christ’s pale face.

“God saved you!” I repeated the words of Vladyka Hilarion to myself. “He saved you both then and now!”

I couldn’t help but recall the only Matins allowed at the Solovki camp in a dilapidated cemetery church. I also remember what my casual companion doesn’t.

At that time I no longer worked on rafts, but was involved in a theater, a publishing house and a museum. It was at that last job that I got into the midst of preparation. Vladyka Hilarion obtained permission from Eihmans2 for all prisoners (and not only for the clergy) to celebrate.

I persuaded the head of the camp to give us the ancient banners, crosses and chalices from the museum for that night, but I forgot about the vestments.

It was too late to go and ask for a second time.

But we didn’t lose heart.

The famous burglar, our friend Volodya (Vladimir) Bedrut, was urgently sent to the museum.

Inexhaustible in his verbosity, Glubokovsky distracted the museum director Vaska (Vasily) Ivanov in the back room, while Bedrut was working with master keys, extracting ancient, precious vestments from chests and showcases, with the stole (epitrachelion) of Metropolitan Philaret (Kolychev) among them.

In the morning everything was returned to their places in the same manner.

(The Mystery of the Resurrection / by A. Chernova. Moscow: The Free Wanderer, 2019. 304 pages. ISBN 978-5-00152-005-4)

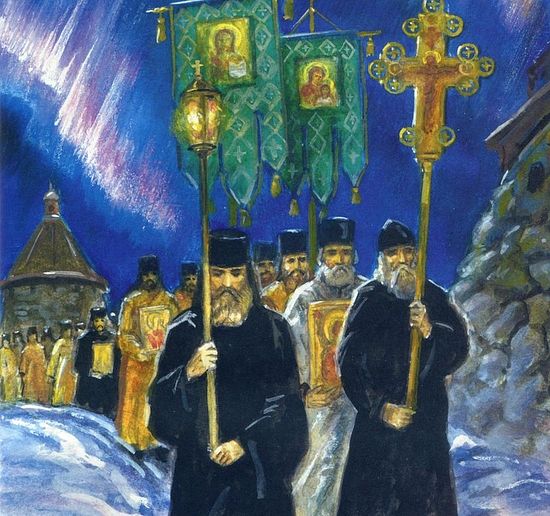

That Matins was unique. Dozens of bishops headed the procession.

Ancient lamps burned with the ineffable colors of the Holy Night, and banners with the faces of the Savior and His Most Pure Mother shone in their radiance.

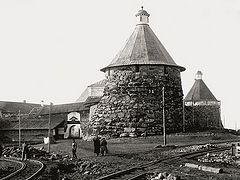

No bells rang: the last bell that had survived the destruction of the monastery in 1921 was removed in 1923. But long before midnight, endless rows of gray shadows had moved towards the dilapidated cemetery church along the kremlin (fortress) wall made of solid boulders and past the austere snow-covered towers.

Few managed to get into the church.

It couldn’t even accommodate the clergy. Over 500 of them were then languishing in prisons.

The whole cemetery was full of people, and some of the worshipers stood next to the trees of a local pine forest.

Silence reigned. Exhausted souls yearned for the blissful peace of prayer.

Ears pricked up and caught the sounds of singing coming from the open gate of the church, and, gaily playing in all colors, pillars of flashes from the Northern Lights roamed across the dark sky.

With a formidable command of a hierarch endowed with unearthly power, Vladyka Hilarion’s mighty exclamation thundered out:

“Let God arise, and let His enemies be scattered!”

Snowflakes fell from the branches of nearby pines, and on the top of the belfry the symbol of the Passion and Resurrection—the Holy Life-Giving Cross that we had erected on that day—flashed, glowing brightly.

A unique procession of the cross appeared from the wide-open gate of the dilapidated church, twinkling with multicolored lights.

There were seventeen bishops in vestments, surrounded by lamps and torches, along with more than 200 priests and the same number of monks, and the countless number of those whose hearts and thoughts were longing for Christ the Savior that wonderful, unforgettable night.

Shining banners created by Novgorod craftsmen solemnly floated out of the church doors; lamps (a gift from a Venetian doge to a faraway monastery) lit up with a magnificent multitude of colors; the sacred vestments and mantles, embroidered by the slender fingers of grand duchesses of Moscow, were freed from captivity and blossomed.

“Christ is Risen!”

Few heard the words of the Good News proclaimed within the church, but everyone felt them with their hearts, and a resounding wave swept through the silence of the snow: “Truly He is Risen!”

“Truly He is Risen!” resonated under the solemn, fiery vault of heaven crowned with the Northern Lights.

“Truly He is Risen!” echoed in the snowy silence of the age-old forest, spread beyond the indestructible kremlin (fortress) walls to those who couldn’t get out of them that Holy Night; those who, emaciated by suffering and illness, lay prostrate in their hospital beds; those who languished in the stinking dungeon of “Avvakum’s Crack”—the notorious Solovki punishment cell.

Those who were doomed to death in the deaf darkness of isolation wards made the sign of the Cross.

The swollen, whitened lips of those with scurvy whispered the words of the promised eternal life while bleeding.

Those whom death threatened every hour and minute walked with triumphant, jubilant singing about death that had been trampled down and vanquished.

Everyone sang... A jubilant chorus of “those in the tombs” glorified and affirmed their coming and inevitable Resurrection, invincible the powers of evil.

And the walls of the prison, built with blood-stained hands, collapsed.

Blood shed in the name of love gives eternal and joyful life.

Even if the body languishes in captivity, the spirit is free and eternal. There is no power in the world capable of extinguishing it!

You who hold us in chains are contemptible and powerless!

You won’t shackle the Spirit, and it will be resurrected to an eternal life of goodness and light!

“Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death...” Everyone sang—an old general who could barely move his legs, a giant Belarussian, those who didn’t remember the words of the prayer, and those who may even have reviled them. They proclaimed the inextinguishable Truth that night. “And upon those in the tombs bestowing life!”

The joy of hope poured into their exhausted hearts.

Suffering and captivity are temporary, not eternal. The life of Christ’s bright Spirit is everlasting.

We will die, but we will live again!

The great monastery—a stronghold of the Russian land—will rise from the ashes.

Rus’, crucified for the sins of the world, humiliated and profaned, will be resurrected.

Through suffering for its immeasurable fall, it will be cleansed and shine with the light of God’s righteousness. And it is not in vain, not by chance that the persecuted, the destitute, those erased from life from all over that great country have gathered.

Was it not here, to the holy ark of the Russian soul, that Russian people had carried their sorrow and hope for centuries?

Was it not by the hands of those who came by vow to this remote northern monastery to atone for their sins and glorify Sts. Zosimas and Sabbatius that these solid walls were erected? Wasn’t it there that rebellious Novgorod river pirates ran in search of peace and quiet, having seen the vanity of the world?

Come unto Me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest (Mt. 11:28).

They came and united in one striving and a brotherly kiss on that Holy night. The walls that had previously separated a St. Petersburg dignitary and a Kaluga peasant, a Rurikid prince and a renegade, collapsed. Sparks from the eternal and the luminous shone out in the smoldering ashes of human vanity, lies and blindness.

“Christ is Risen!”

That was the only Matins celebrated in the Solovki Labor Camp.

Later it was said that it was permitted because the OGPU wished to make a brilliant display of their “humanity” and “religious tolerance” before the West.

I will never forget it.

Solovki, 1925

An excerpt from the book, The Eternal Lamp