The memoirs of Priest Pavel Chekhranov (1875-1961) evoke the images of outstanding hierarchs and priests while chronicling a tragic period of our country’s history. Fr. Pavel knew these future New Martyrs of Russia and shared with them the hardships of destiny. His memoirs were published by his son Vitaly Chekhranovwho fought in World War II. We offer our readers two fragments from these memoirs.

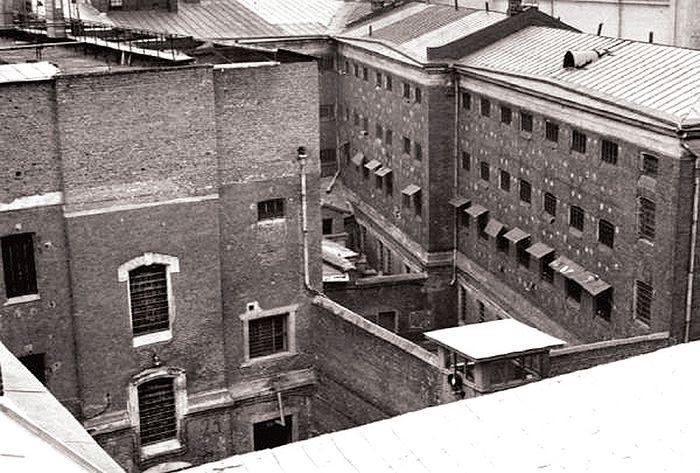

Pascha in Butyrka Prison, 1925.

The morning started with roll call. They gave us boiled water… At noon we had the usual herring soup for lunch and at 5 pm they served us wheat porridge and tea. After that, some inmates sang, while others talked. It was an early Pascha that year. The first day of Easter was celebrated: The doors were unlocked and kept wide open… In the morning, inmates from other cells came to give Paschal greetings and exchange triple kisses.

Herman, the bishop of Volokolamsk Monastery, came to our cell and told protodeacon Novochadov and me to stand in the middle of the hall. Then he said, “We are going to sing “Let God Arise!” A guard passed us by, carrying his keys. He was smiling and nodding, as if encouraging us to keep on singing. The bishop sang tenor, I sang alto, and the protodeacon sang bass. The words, “Let God arise… So let sinners perish before the presence of God…” rang out in the hall. All the inmates came up to the doors of their cells and listened to us until we finished: “And so let us cry aloud: Christ is risen from the dead!..”

We three became the heroes of the Butyrka prison for blessing it with our Paschal singing. Thanks are due to Bishop Herman and the guard for making it possible. Remember them, Lord, when thou comest into thy Kingdom!...

When I learned that there was a group of clergymen in the next cell, I asked the guard for a transfer. My request was satisfied. In that cell I met Archimandrite Alexy, abbot of Donskoy Monastery (later Archbishop of Novonikolayevsk and Yakutia), Dimitry, Archbishop of Kiev, and Priest Vasily Slavuchevsky.

The shot-caller of our cell was a criminal whose nickname was Tsygan (Gypsy). On Saturday he said to his cellmates, “Since we have clergymen, bishops and others in our cell, I think that out of respect for them we should ban all swearing, cursing and foul language.” Then he said to the bishop, “If you you’d like to perform services today and tomorrow, I’ll allow it in my cell.”

Pascha on Solovki, 1926

This was the most difficult Pascha of the four that I had celebrated during my imprisonment from 1923 to 1926.

The prison term that all members of our group suffered for the honor of our church and St. Nicolas parish was to expire on March 30.

However, in the morning we heard the most upsetting news: the prison term for Bishop Mitrophan and myself had been extended. We didn’t know why or for how long. It could be a week or ten weeks. “Ah,” I thought. “Once again, I have to suffer more than the others! It’s either because I’m the most sinful of all or because God loves me more than the others!”

After looking enviously as Fr. Alexy and six other priests were leaving, I was left to wait in agonizing suspense for the day when Anfilov1 would call me.

The camp was surrounded by ice, snow and barbed wire. On top of the watchtowers, the guards wearing sheepskin coats cursed this island as they watched over the “hardened criminals”: bishops, priests, protodeacons… I am sad. Still, I’m saying to myself, “Does anything happen in life by chance? Doesn’t God control this world and your life? Would He wish you anything bad? Wait and you will see that this extension is a blessing in disguise.”

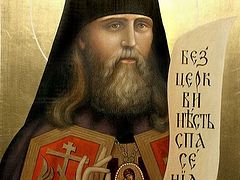

About two weeks have passed. My depressed thoughts were interrupted by a Georgian officer named Yashvili. He was an inmate too, but they assigned him the duties of a labor supervisor. “Today brought they Hilarion in with the new group of convicts!” he said to me. “Really!?” I exclaimed. “Yes, they are searching everybody now in the squad quarters…” I decided to go and see my dear archbishop, even though it was about 10 pm. They wouldn’t let anybody in until they finished searching the new arrivals. After a moment of consideration, I took a pack of papers, some blank inventory forms and pencils and went straight to the quarters, pretending that I was going on some official business.

There was hustle and bustle in the quarters, as they were rigorously searching the new arrivals. I looked around and saw Archbishop Hilarion (Troitsky) in a brown caftan sitting on the plank-bed. As soon as he saw me he ran up to me, crying “Father Pavel! Father Pavel!” We greeted each other with the kiss of peace. Unfortunately, the squad officers and camp warden assistant noticed our friendly meeting and insisted that I leave until the search was over, even though I showed them papers and pencils, trying to convince them that I was here on an official business.

Pascha was approaching. There were many people in the camp. Logging operations were suspended because of the spring thaw, and more than a thousand convicts were sent back to the camp, even though the camp’s capacity was only 800 people. The recreation room was shut down and converted into a cell with plank beds. In other barracks, plank beds were placed in the halls and a third level was added to bunk beds. Even under such a difficult circumstances we wished that we could have a prayer service. “How can it be!” I thought. “It is difficult to walk through the crowd and talk, but how can we not sing “Christ is Risen!” on a Paschal night?

Only Archbishop Hilarion and Bishop Nektary agreed to perform the Paschal service in the unfinished bakery. The building had only doorways and window openings, but the doors and windows were not yet installed. Other bishops decided to perform the service on the third level just under the ceiling of their barrack, which was located next to the squad officers’ quarters. However, I was determined to sing the Paschal service outside of the barrack, so that we wouldn’t hear any foul language while we sang. We agreed to do it.

Holy Saturday came. People who returned from the logging operations were packed like sardines in the prison yard and barracks. In addition, we faced a new obstacle. The prison warden issued an order to the squad officers to prevent any attempts by inmates to have a church service and forbid any movement of inmates between the barracks. I heard this sad news from Bishops Mitrophan and Gabriel. However, I insistently told “my clergy” that we should try to hold the service in the bakery. Bishop Nektary agreed right away. Although Archbishop Hilarion agreed reluctantly, he still asked me to wake him up at midnight.

Sometime after 11, I came to wake up Archbishop Hilarion who was sleeping with his large body stretched out on a plank bed. I patted his boot and he sat up. “It’s time”, I whispered. The barrack was asleep. I got out. Walking in single file, we headed toward the unfinished bakery that was situated behind the barracks. We agreed to sneak in there one by one, rather than going all together. When we got inside, we chose the wall that would better hide us from the eyes of those who might be walking on the path. We pressed our backs to the wall. Archbishop Hilarion stood in the middle, Bishop Nektary was to the left and I was to the right. “Proceed”, said Bishop Nektary. “Should we start with the Morning Service?” asked Archbishop Hilarion. “No, let’s start from the Midnight Office, and do everything in order”, said Bishop Nektary. “Blessed is our God…”, said Archbishop Hilarion quietly.

We started singing the Midnight Office. “He Who in ancient times hid the pursuing tyrant beneath the waves of the sea…” we sang. Strangely, these words with their enchanting tune resounded in our hearts. “Is hidden beneath the earth…” Never before had we felt the tragedy of being persecuted by pharaoh so acutely. Surrounded by the white sea covered by white ice, we stood on the floor joists as if we were in the choir loft, fearful that the guards might spot us. Yet our hearts were full of joy, because we were performing the Paschal service despite the strict orders of the prison warden.

We sang the Midnight Office. Archbishop Hilarion gave his blessing to proceed with Matins. “Let God arise, and let His enemies be scattered,” whispered Archbishop Hilarion, staring into the darkness of the night. We sang, “Christ is Risen!” “Should I cry or laugh with joy?” I wondered. How we felt like singing those beautiful irmoi in full voice! But we had to be cautious and keep our voices low. We completed Matins. “Christ is Risen”, said Archbishop Hilarion and we exchanged triple kisses. Archbishop Hilarion pronounced the dismissal and returned to the barrack. Bishop Nektary wanted to perform the Hours and Typica, and so we did. I was the priest and Bishop Nektary the psalm reader. That was his decision, for as a true successor of the apostles he knew all the hymns and texts by heart.

The next day I invited Archbishop Hilarion for coffee to my barrack. “Have you tried coffee a la Vienna?” asked the Archbishop laughing, and told me how to prepare it. The next day, Bishop Nektary and I performed the service together, walking on the path. This day also seemed like a feast day for me just like the first time when we performed the service.

Archbishop Hilarion remembered that Paschal service too. His term of imprisonment had expired in December that year, so they had already moved him from Solovki to the mainland, because navigation was no longer possible. However, in December I received a letter from him: “The wheel of Fortune has turned back and they are transporting me back to Solovki island…”

Indeed, according to new orders from Moscow his prison term had been extended by three more years. “They sent be back for ‘re-training’”, Archbishop Hilarion joked. In May 1927, he wrote to me, “I remember last year’s Pascha. How different it was from this one! We had such a solemn service then!”

Yes, the Pascha of 1926 was unusual. While the three of us performed the service in an unfinished bakery, the city clergy in Rostov were also performing the Pascha service in the cathedral filled with electric light and accompanied by the marvelous singing of I.F. Kovalev’s choir.

Nevertheless, we consider that our Paschal service in Kem province with Archbishop Hilarion under the stars, in a bakery without windows or doors, without any mitres or brocade vestments, was dearer to God than the magnificent service in Rostov.

In the Europe which was created by the Second World War, divided into two blocks, each in need of a revolution that would end the abuses and injustices of capitalism and the privileges of a bureaucratic caste, collective faith does not exist, unfortunatelly.

In times when religious faith or hope predominates, the writer functions totally in unison with society, and expresses society's feelings, beliefs, and hopes in perfect harmony.

How inappropriate to call this planet Earth when it is quite clearly Ocean.

http://marius-rescript.blogspot.ro/2018/03/god-is-in-charge.html