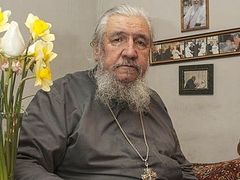

An Orthodox priest is a miracle, but few lives have been so miraculous as Fr. Pyotr’s. Deacon Andrey Radkevich had the chance to interview this amazing man before he died in 2005.

Archpriest Pyotr Bakhtin Once (it was the beginning of the present century) at the editor’s office of one of well-known magazine, I received an assignment to find a priest who fought in the Great Patriotic War [World War II]. I was to write a catchy and fascinating story for their Victory Day May issue.

Archpriest Pyotr Bakhtin Once (it was the beginning of the present century) at the editor’s office of one of well-known magazine, I received an assignment to find a priest who fought in the Great Patriotic War [World War II]. I was to write a catchy and fascinating story for their Victory Day May issue.

I had a tough time finding someone, even after making calls to dozens of churches and reaching out to numerous households. Only once did I get a call from a priestly family residing not far from Moscow—there was a priest, but he was in a feeble state of health and couldn’t be interviewed.

Another Moscow church (of the Deposition of the Robe on Shabolovka) had a rector, a war veteran, who even continued to serve despite his advanced age. However, he was driven to church from somewhere in the Moscow region to conduct services exclusively on the great feast days.

Therefore, I figured that the editorial staff must have miscalculated their options; even hypothetically, if this man was around twenty years old in 1945, he should have been in his late 80s today. How could one continue to serve at this age? It seemed next to impossible. Therefore, I thought I’d never find one.

At the same time, there was some kind of Providence in this assignment to find a priest before Victory Day, because one day, one of my acquaintances, in response to my requests and investigations, announced the name: “Fr. Pyotr Bakhtin”.

Finding Fr. Pyotr Bakhtin

I obtained his phone number, called Sergiev Posad where he resided and asked: “Father, did you fight in the war?”

He answered, “Yes, I did.”

The next day I went to see him at his house in Sergiev Posad where he shared the whole story of his life—truly and thoroughly wondrous at every twist.

I should preface it by saying that he was commemorated as dead in fourteen different funeral services over the course of his life.

Do you know anyone who was twice remembered as dead while still alive?

Or, knowing anyone who was remembered as dead once… while alive?

I think you’d have to look really hard to find one.

But Fr. Pyotr’s funeral was served fourteen times before he actually died, that is, while he was still alive.

His whole life was full to the brim with similar stories, each more amazing than the next.

Disenfranchisement of the “kulaks”—Russia’s wealthy peasant class

When he was a little boy, his family lived near the city of Orel. His father was a well-off, hard-working peasant. As soon the Communists issued a decree on the disenfranchisement of the population, all of them, including his mother, father, younger brothers and sisters were repressed. Just like the thousands of other unfortunate, long-suffering citizens of our country, they were loaded into freight train cars and, in the dead of winter, taken far away to the steppes of Karaganda.

Once there, an army of the repressed was discharged off the train in the middle of empty, wintry fields and steppes.

One hundred people went to fight in the war. Only one of them returned

What were they supposed eat, where were they to live, or how were they to keep themselves warm? They had absolutely nothing: no housing, no food, whatsoever. All they had all around there was an empty field and freezing, wintry weather. They had to dig out mud huts. Within the next few months, his father, as well as all of his brothers and sisters died from freezing weather and hunger. The only survivors left in their family were he and his mother.

After some time, they were able to settle down in Karaganda. Pyotr was drafted to fight in the Finnish war. One hundred people went from his town to fight in that war and then in Second World War. He was the only one who came back out of that hundred. Ninety-nine perished in the war.

A “Killed in Action” notice

During the World War II, Pyotr Bakhtin was in command of the Katyusha artillery battalion. At the Battle of Königsberg, he was seriously wounded and lost consciousness.

Once the battle was over, his military unit couldn’t locate him on the battlefield. They sent a “killed in action” notice to his mother: “Missing in action. Died a hero’s death.”

His mother, a devout Christian, held a funeral service in his memory at church.

A little while later, after he had undergone treatment at the hospital, he located his unit and his mother received another letter stating that her son was found alive.

Time went by and the whole ordeal had happened again: she received another “killed in action’ notice. She ordered another funeral service in his memory… Another letter followed soon saying that they made a mistake and “your son was found alive…”

Can you imagine the range and intensity of the feelings his mother’s heart had to endure? First, living through grief over losing her only son. Next, it turned out that she buried him far too early and he was alive all along. Before she had enough time to rejoice at having him back alive, she was told to bury him again—only to be told again later that he was alive… How can a person endure such an ordeal?

That’s how Pyotr Bakhtin had two funerals out of 14 while alive, while the remaining twelve took place during peaceful times. We will have more on this below.

Defense of the high ground

Fr. Peter Bakhtin was decorated with several military orders and a score of medals. He said it wasn’t such an easy thing to earn an order during the Great Patriotic War.

One of his orders was awarded to him as commander of the Katyusha artillery battalion for a high ground defense operation. Together with his servicemen, he held their position until there was no ammunition was left to defend it. The fascists kept crawling up from all sides. That’s when he took the last recourse: He radioed his battalion’s position to other “Katyusha” units located above the battle and ordered an airstrike on himself.

The shells plowed up every millimeter of the high ground and nearby area. Almost all of the “Fritzes” were wiped out, but he and a handful of his comrades-in-arms survived.

Capturing a prisoner for interrogation

He received his second order for capturing one of the villages.

After the battle, he went to take a closer look at the village and saw a dig-in German “Tiger” tank. A non-runner, it was used as a pillbox for a machine gun position.

All of a sudden, he saw a gun-toting German soldier coming around the corner of a hut located next to the “Tiger.” Then came another, and another, and then a fourth one… Bakhtin counted fourteen armed Nazis. When they noticed him, for some reason, they got spooked and took off, even though they obviously had the numerical advantage.

He thought it was odd. Quite possibly they were still under the impression of the battle they had just lost, or went panicking. They could also have deduced that, in another second, a detached force of Russians with reinforcement would show up from around the corner in addition to this loner.

In any case, they took to their heels away from him. But instead of running in the opposite direction, sprinted after them.

I asked him, “Batiushka, how was it that you had no fear? At any moment one of them could have turned around, fired a shot, and you’d have been a goner.”

He explained, “By the end of the war, you no longer have any fear. You go to the battlefield, hear the bullets whizzing by, shells bursting everywhere, shrapnel spraying around, but all you think is, “Who cares, I’ll be killed anyway,”—and you don’t even stop to cower.

So, he rushed forward and overtook a young German straggler. His first thought was to finish him off. But the German started crying, pleading:

“Kinder, kinder!” and gesturing westwards.

Pyotr understood that he had a child back at home. He took pity on the fascist and delivered him alive to the command unit.

This German soldier wasn’t just a nobody but a treasure trove of classified information, who told the Russians about the location of fascist military units, heavy artillery, and gun posts.

Using his points, we sent the tanks forward, our planes took off, and the infantry launched an attack.

As a result, this particular sector of the front saw a truly successful offensive.

When one of the leaders of this offensive operation asked, “Who got the prisoner for interrogation?” he was told, “Bakhtin, the battalion commander.”

“Award him with the Star of the Hero of the Soviet Union!” ordered the commander-in-chief.

However, during the award document submission, it was discovered that Pyotr Bakhtin’s father was a “kulak.” Under the existing political realities, the Star of the Hero award could not be awarded to someone like him, so he received another order.

The last order

Pyotr Bakhtin was awarded his third order in the waning days of the war for the combat outside of Prague.

To protect his soldiers, he went scouting on his own to see where the Nazis located their machine-gun nests, permanent emplacements, log pillboxes, artillery, and defense works. In other words, he scouted for the aim-points that could be later hit by his battalion’s “Katyushas”.

As he was busy recording the aim-points on a temporary map, he was discovered and hit with machine gun and mortar fire. All he was able to do was to jump, roll down in one of the shell craters, and lose conscience from his wounds.

When Pyotr Bakhtin regained consciousness three days later and opened his eyes, he saw Czech doctor leaning over him. The doctor uttered:

“Well, thank God, you are alive. It wasn’t for nothing that I prayed to God for you.”

Bakhtin wondered aloud, “What God? I’m an atheist.”

“But I saw it—you have a cross pinned underneath your service shirt.”

“Ahh, that,” explained Pyotr. My mother gave it to me when I went off to war.

The doctor waved him off. “Oh well, here is the book, so try to figure it out yourself,” he said, holding out a Bible.

Fr. Pyotr Bakhtin confesses that ever since, the question of whether there is God or not remained the most important question of his life.

Going home

After the war was over, our military units were stationed in Europe, but no one was allowed to simply take his discharge and return home. They had to enter the Communist Party first.

He entered the Party and, in 1947, returned to his native Karaganda, to his mother.

You need to thank God. Enroll in the seminary

His mother tells him:

“Sonny, out of the one hundred men who left Karaganda for war, you are the only one who came back. You should thank God. Enroll in the seminary.”

So, he thought, “Where else would I get the best knowledge of God, whether He exists or not, if not at a seminary, isn’t that what they do there?

Resignation from the Party. His trial

He traveled to Sergiev Posad (called Zagorsk at the time) and to the seminary there from his native Karaganda.

He was told, “Well, but we can’t accept party members.”

He goes back to Karaganda and declares to the local party committee, “I want to turn in my party membership card.”

Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, 1960s

Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, 1960s

At first, the party bosses thought he was joking. It was such a rare case in those times when someone voluntarily left the Communist Party; it was like asking: “I want to be jailed and even executed.” However, when they realized how serious he was about it, they held a party bureau meeting. That meeting was attended by as many heads of the local party cells and party organizers as there were factories, mines, and other enterprises around Karaganda.

The trial commenced. One of them got up and spoke out: “What is this? We are fighting religion and he decides to go to the seminary to become a priest…

Another one got up and berated him: “He is against our party and Comrade Stalin. He throws his party card at us today, and tomorrow he will come and shoot us in the back.”

A third one same the same thing, and a fourth…

Bakhtin saw that he wouldn’t be allowed to leave this room and he’d be arrested on the spot.

“All I could do,” he recalled, “was to silently recite “O Virgin Theotokos, rejoice!...” (a short prayer to the Mother of God. – author’s note), rise, and say:

“Who on earth are you to lecture me? I am a soldier and a war veteran. Look at you and your jelly-bellies—my father with whom you reproach me was a “kulak”, but he died from hunger. Comrade Stalin studied at the seminary and Marshal Vasilevsky graduated from the Theological Academy, so I also want to know if there is God or not. We have no law prohibiting it.”

That’s when they ruled to officially record the following: “Developed schizophrenia, to be expelled from the party.”

It meant they couldn’t expel anyone from the party without a diagnosis of insanity as the best-case scenario, because an alternative solution for such a decision was either a jail or even execution.

First exam

So, here he was, traveling back to the seminary in Sergiev Posad for the entrance exams.

At his first exam, he was asked to read in Church Slavonic. In today’s terms, it doesn’t seem like too complicated of a task. It even sounds like an easy thing to do. But, in the context of those times, it was probably a truly hard question to answer.

You probably know that a scroll is used instead of missed letters in the Church Slavonic texts. A missed letter should be inserted according to the meaning of either the text or the dropped symbol. “Бог” (Russian for “God”.—Trans.) is written as “B~g”, or “Богородице” (“Theotokos”.—Trans.) as “B~tse”.

Fr. Pyotr says: “I was a soldier, so I read “[Bi:~Dgi:]” instead of “Бог” and “[Bi:~tse:]” instead of ‘Theotokos.’”

He was booted out of his first exam.

Second exam

On the second exam, he was asked, “What tones do you know?”

The question related to the Stichera and Troparion melody tones used in church practice. There are eight each. The church hymns are sung during the church services using those melodies.

He, of course, had never heard of them, either, so he tried to use his frontline ingenuity and resourcefulness.

He replied, “What GLAZZY (misspelled Russian for glazy, “eyes”, instead of “glassy”, tones.—Trans.) are you talking about? I’ve got two eyes! I have no idea, which one you want me to talk about.

That’s how he was booted out of his second exam.

As an experiment

Pyotr was terribly upset and kept thinking: “I’ve burned all my bridges back home, I was expelled from the party, and now I’ve been cast out here.”

Feeling hopelessly bitter, he came up to the bulletin announcing the list of names of the fortunate souls admitted to the seminary. But there, to his great surprise, he sees his name among those admitted, with an extra note added by a bishop beside his name: “To be admitted as an experiment.”

It was quite an interesting experiment, to say the least: He spent the next two years debating with his seminary instructors whether there was God or not!

What if someone tried to debate with the instructors on this topic at a theological college or seminary today! He could easily study for four or even five years and never find faith. What would come of it? An unbelieving priest?

However, at the time, he was admitted as an experiment.

Later on, Stalin (as Fr. Pyotr told me) was informed that eighteen front-line officers had entered the seminary.

Stalin uttered, “That’s okay. Let them go. It is a one-way road and there’s no return.”

In the years to come, most of those combat veterans were either jailed or executed. Only two of them, him and another priest, returned from the concentration camps alive.

Arrest

When he was halfway through his second year in the seminary, someone suggested to him, “Go to Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan and find out what is the true and right faith.

Whether it was the advice of a clairvoyant or of a provocateur, we don’t know. But as soon as he landed and deplaned, he was met by plainclothesmen (NKVD in the 1930s and MGB in the 1950s) who demanded without giving any reason, “Remove that cross!”

They meant the cross his mother had given him as a blessing before he went off to war.

In response, he asked them, “Are you the ones who put it on me, that you can take it off of me?

He was immediately hit in the face and beaten up.

He was arrested, taken to a local jail, and thrown into a cell teeming with criminals. As soon as the door banged after him, one of the felons approached him, and drawing a knife, said viciously:

“We’re gonna cut you up. What party are you from?”

Pyotr replied, “I know no party, I was studying to be a priest…”

Archpriest Pyotr Bakhtin I am only guessing, but there was probably some kind of a code name or a test, as I was told later, in contemporary prisons. When a newcomer enters the cell, he is tested in the following manner: The criminals throw a face and hand towel under his feet. If he picks it up and hangs it, he is a newbie and will be beaten. When he wipes his feet on it, he is a regular, who’s been jailed before. He will be allowed a place of honor, such as a better berth. So, it was some kind of a test.

Archpriest Pyotr Bakhtin I am only guessing, but there was probably some kind of a code name or a test, as I was told later, in contemporary prisons. When a newcomer enters the cell, he is tested in the following manner: The criminals throw a face and hand towel under his feet. If he picks it up and hangs it, he is a newbie and will be beaten. When he wipes his feet on it, he is a regular, who’s been jailed before. He will be allowed a place of honor, such as a better berth. So, it was some kind of a test.

Or, it could be that the question they asked Fr. Pyotr, “What party are you from?” related to the prison transport party he had arrived on. It could also have referred to a political party.

Pyotr Bakhtin tells them, “What party? I know no party, I was studying to be a priest…”

They promised: “We’ll check that.”

In three days, the same criminal comes up and says, “You were right. You are a disciple of Jesus Christ. And He saved a crook…” (Meaning the “good thief” who was crucified on the right of Jesus Christ and received the name, “crook”, in criminal jargon).

There is room for both God and devil in any man’s heart

“He saved a crook and so you won’t have to work here. We’ll earn enough for you to get your chow.”

That is to say, that out gratitude for the divine goodness Christ showed to one of “them” two thousand years ago, they decided to repay Pyotr with the privilege of receiving food without having to work.

Later on in the camp, Pyotr came to believe that in any man, in any man’s heart, there is room for both God and the devil—no matter where he be, in a seminary, a prison full of criminals, or anywhere else.

His cross is retrieved—perhaps the only case in Gulag history

One of Pyotr Bakhtin’s inmates at the camp was either an NKGB or MGB (or whatever it was called then) officer. He was jailed for failing to comply with a “plan”—he didn’t put enough people to prison. As a former MGB agent he knew every letter of the law, and he helped Pyotr write about twenty letters to different government institutions asking them to retrieve his cross (the one he was imprisoned for in the first place). This correspondence reached the Kremlin. Unexpectedly, they received a telegram in response from the Kremlin regarding the cross: “It is a matter of your own conscience.”

When the local guards saw the cables Bakhtin had received from the Kremlin, they decided not to mess with him, to be safe and avoid any risks. What if it turns out that he has a toehold or a powerful patron of some kind inside the Kremlin? They took him to a safe room where his scanty valuables were held since their confiscation at the time of arrest: his frontline medals, orders, and the cross his mother had blessed him with before he went off to war.

When the cross was returned to him, tears ran from his eyes, and he still cherishes this story as a miracle—for that cross was the reason he was put in prison. It was probably the only time in GULAG history when an inmate was allowed to retrieve his cross.

The New Testament

More than that, he was even able to retrieve his New Testament. This was even more inconceivable. Again it was with the assistance of his fellow inmate, an MGB officer.

He said, “If you write: “Please return my New Testament book,” you obviously won’t get anything. But you should write: “Please return my textbook.” You studied to be a priest and you need your study books. This way, hopefully you will succeed.”

Sure enough, remembering that fateful telegram from the Kremlin, he saw no objections against this request as well—but he was told to stay away from evangelizing the inmates.

It was another truly exceptional case in the history of GULAG in the age of militant atheism, when so many were imprisoned for their faith in God, and many more executed. At the Butovo shooting range near Moscow alone, between 100,000 to 200,000 faithful were executed specifically for their faith. But how many more such places are there elsewhere in the country?

To be continued.