On Sunday, February 7, when the Church celebrated the memory of the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church, Archimandrite Antony (Guliashvili), a retired cleric of the Church of St. Alexander Nevsky in Tbilisi, who served at the altar of God for more than fifty years, departed to the Lord. In 2017, he spoke with Pravoslavie.ru about the peculiarities of faith in the Soviet era and in our modern times.

We had a more responsible approach to the faith during the Soviet times

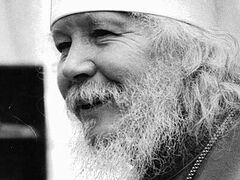

Archimandrite Antony Guliashvili —Fr. Antony, we would like to ask you about how the faithful of the Soviet era differed from the faithful today?

Archimandrite Antony Guliashvili —Fr. Antony, we would like to ask you about how the faithful of the Soviet era differed from the faithful today?

—We had a more responsible and serious approach to the faith during the Soviet era. The truly faithful people in the Soviet era would go pray in a distant place, for example, in a monastery somewhere so others wouldn’t see them, but they didn’t do it because they were afraid. In my opinion, they simply didn’t want to do any harm to those who called themselves atheists, because they had the task of catching and punishing the faithful. They preserved their Orthodoxy, going far off to the mountains, to a monastery to pray there, but they didn’t hide, because they knew there was no hiding from God. Now there are more passersby and people who just stop in than there are parishioners.

Of course, all this is just my opinion; and I think this despite the fact that I personally suffered then, in the Soviet times, what perhaps shouldn’t be called persecution, but rather a mild punishment, having spent seven months in a camp.

—Why were you sent to the camp?

—It’s a long story, but I’ll tell you briefly. One time, Vladyka Nestor (Tugai), under whom the Kiev Caves Lavra was closed in Soviet times, came to visit us in Batumi, where I started my ministry in the Church. Our ruling hierarch, now Patriarch Ilia II of Georgia, was in Rhodes, and I was chosen to meet our guest. I met him as appointed and as I could. And after Vladyka left for Kiev, he invited me to visit him, so I went there sometime in September. When I was there, I said, “Vladyka, bless me to go to Pochaev for the feast of the Pochaev Icon of the Mother of God.” He blessed, but asked that I return to Kiev in time for my name’s day—the feast of St. Alexander Nevsky. I was still Alexander then. I went to the Pochaev Lavra, took part in the Divine services, and then I got ready to go to the bus station to go back to Kiev. But there was a large cell of atheists-God-fighters in Pochaev. A heated argument, a polemic broke out at the bus station, and the head of this atheist cell spat on my cassock. I couldn’t tolerate it, so I hit him. This was the only time I ever hit someone—when he spit on my cassock.

The offender told me, “I’m going to come at you with everything I’ve got and put you in jail.” They asked me at the trial if I considered myself guilty. I said, “Of course I consider myself guilty, but not before you—before God. I gave the Lord an oath when I received the priesthood that I would never raise my hand against anyone. Then I committed this hooliganism.” In the end, I was sentenced as a hooligan.

The most interesting thing is that the penalty called for under this article ranged from a fine to a year in prison, and they gave me a year. The judge was a woman with the last name Konotop, and the prosecutor was also a woman—Rubleva. They told me at the end, “This year will make you think about taking off that sack.” I was in my riassa during the trial. But I told them the only thing I was thinking about was that no matter what they did, no matter how hard they tried, I would get out of there and remain a priest. That made them even angrier.

—So why do you think it was better in the Soviet era if they even put you in jail?

—Because the Lord helped us endure all of this. They held me for four months after the trial with one purpose—to reeducate me. The deputy chief of indoctrination Vlasenko was working on it. Then there happened a story that I recall with pride. One time I really needed to go to the infirmary, so I asked, and they had a guard take me. Suddenly he asked me, “Where are you from?” “From Georgia,” I said. “I served in Georgia,” he said. When you’re in a foreign land, every word about your homeland is pleasant to hear, and I opened up to him. I told him this deputy chief was tormenting me, that he wanted to completely reeducate me so I would give up my faith. How could I have known that he would report me to this same deputy?

The deputy chief summoned me that same night: “What are you doing?! Why are you slandering me?! Don’t you know what I can do with you for slandering a government employee?” He started yelling at me with all sorts of bad words. This was at night. I thought, “Lord, what should I do? Holy Hierarch Fr. Nicholas, help me; this is my first time in prison.” He was still swearing and raging at me, and I was talking with God in my head, as I could. Then a thought overtook me. I suddenly said, “I had a witness who saw you torturing me.” The deputy chief flashed like a rainbow. First his face turned white, then it turned into a red ball, then a pink ball. “What witness?” he shouted. He didn’t understand what other witness there could have been. He was enraged, trying to remember when he made the mistake of talking with me in front of witnesses. I was standing there, and my only hope was in God. Then I pointed to a small bust of Lenin that was standing on the safe, and I said, “You said he lives forever. So he is my witness.” You can’t even imagine what happened to him! He started to squirm, then he grabbed a bottle of ink and launched it at me.

“I didn’t want to leave the camp”

There were various people with me in the camp—political prisoners, petty thieves, and hooligans. And when I was released seven months later—I don’t know if you’ll believe me, but I said, “I don’t want to leave.” I had become such good friends with these people that I wanted to stay with them.

—Was this prison or a camp?

—A camp in Chernigov. My time there was a big lesson for me.

—A lesson in what?

—A lesson in how a man can become a beast. If I had broken down, they would have broken me for life. But the Lord helped me endure.

I think the other prisoners really respected and loved me. There were ninety-five of us in the barracks, and someone would receive a package almost every day. You could only put things like sprats in tomato sauce, dried bread, garlic, onion, and stuff like that in them. That’s it. So, someone got a package nearly every day, and they would give me something from it—onions or garlic or something like that. “Here, this is for you, Batiushka.” And five or ten minutes later, someone else would ask me, “Batiushka, do you have any onions or garlic?” So I would give him what I had just been given, and everyone was content, and everyone called me Batiushka.

A real priest is one who wants to heal human souls

Church of St. Alexander Nevsky in Tbilisi

Church of St. Alexander Nevsky in Tbilisi

—But still, those were times of a great lack of freedom. But now the Church has gained its freedom, and many more people are turning to the faith.

—Turning to the faith… And who should turn to faith? “A most troublesome time is coming; the enemy is rocking and trying to overturn the Church. Many completely unchurched and even unbelieving people have entered the ranks of the clergy and they are doing their work.” Fr. John (Krestiankin) said this twenty years ago. Since random people have even become clergy, what can be said of the laity?

If a doctor heals human bodies, then a priest should heal human souls in confession, giving a person a penance that he can bear and truly benefit from. To do this, he should psychologically study his spiritual children—what makes them tick, what they love and don’t love, what they can do and cannot do. What is a penance? It’s spiritual healing. In fulfilling a penance, a man heals his soul. And if he fulfills it and I then remove it, I remove this cross from him. But I have to know him. Let’s say he’s physically strong but in a difficult financial situation, and I give him a penance like this: “There is an elderly woman who lives there on the edge of the village. For what you’ve done, go chop wood for her and heat her stove all winter.”

And another person is financially secure, but such physical labor is not for him. So I say to him: “You know what, let’s make this agreement. Send a certain sum to this address for a year, or two, or maybe ten months, but without a return address. It’ll be good for you to help someone financially, and they’ll pray for you.”

But I have to really know this person and what he is capable of. Yes, a priest should be strict. St. Ephraim the Syrian says in his Spiritual Psalter: “When a spiritual guide punishes his student, he does not beat him out of hatred, but out of the desire to benefit him; and, because he loves him, he punishes him.” If you tell someone who has sinned a lot to do ten prostrations a day for a month, but he’s disabled and has bad legs, then what kind of result will there be? He’s a believer, and truly repents, and wants to be delivered from sin, and is afraid to violate the penance. But he’ll make these prostrations and curse me that I’m such a beast, giving a sick man such a penance. I’d rather give him a penance that he can fulfill with love and won’t be a physical burden to an invalid—for example, knowing that God will forgive him his sin for this penance. But it’s very difficult to be such a priest, of course.

“If you could only have seen how his face immediately brightened and his eyes lit up!”

I had this one case. I was twenty-six, serving as a priest in Batumi. At that time, our ruling hierarch was Vladyka Ilia, now the Patriarch of Georgia. I was hearing one young man’s confession. What sins does a guy his age have? He went out with some girls, and stole flowers from a flowerbed to give to these girls. And I looked him in the face and saw that his eyes were completely extinguished, that all hope of being a normal person and being saved was completely gone from them. I asked him how old he was—seventeen. A little while later, he came to me for confession again. My memory is very good in this regard, and I well remember the confessions I heard fifty years ago. And I asked him again how old he was that he managed to sin this way. “Seventeen, Batiushka,” he answered. I saw that he was answering listlessly, and basically, after this confession he could just go drown himself in the sea or hang himself. I could see the utter desperation in him. So I decided to “tell a lie for salvation.” “Listen,” I told him, “I was fourteen when I committed these kinds of sins.” If you could only have seen how his face immediately brightened and his eyes lit up! And what do you think? It’s fifty years now that he’s a monk laboring on Mt. Athos.