On May 16, the festive opening of a memorial to Metropolitan Pitirim of Volokolamsk and Yurievsk, a man who is the personification of an entire epoch in the history of the Russian Church and Russian culture, was held in Volokolamsk. We spoke with Metropolitan Gabriel of Lovech, one of the most well-known hierarchs of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, who was a spiritual child, friend, and colleague of Metropolitan Pitirim, about the Russian hierarch’s outstanding ecclesiastical activities and the life of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church today.

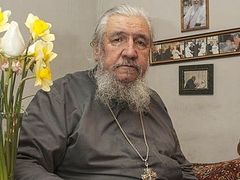

Metropolitan Pitirim of Volokolamsk and Yurievsk

Metropolitan Pitirim of Volokolamsk and Yurievsk

—Vladyka, tell us about how you came to the Church and how you met Metropolitan Pitirim.

—While in my first year at the Civil Engineering Institute, I was honored, by the grace of God, to meet an outstanding hierarch of the Bulgarian Church, Vladyka Parthenius (Stamatov) of Levki, who was truly a man of a highly spiritual, pure life, and very literate and intelligent.

I was a believer, but at the same time I was not very familiar with Church life, because we were inculcated at school with atheistic ideas and principles that have little in common with Christianity Vladyka Parthenius led me along the path of Church life, and I gradually began to notice its immeasurable beauty.

One of the most striking episodes of my time entering into the life of the Church was meeting Schema-Igumena Maria (Dokhtorova), which happened thanks to Vladyka Parthenius. Mother Maria lived at the Skete of St. Parasceva, not far from Sophia; she was an example of the true ascetic life. It was always warm and joyful with her. I was twenty-two then when I began to communicate with this ascetic, and she was seventy-seven. Soon the last nun of Mother’s convent reposed, and I decided to switch to correspondence courses at the institute so I could be near Mother and help her out. All of the spiritual treasures I acquired during those years were given me by Mother Maria.

Schema-Igumena Maria (Dokhtorova)

Schema-Igumena Maria (Dokhtorova)

One day, Mother and I were looking over the official Russian Church calendar, and when we came to the page with photographs of hierarchs, Mother found the photograph of Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechaev) of Volokolamsk and Yurievsk, and solemnly said: “This is one of the most ascetic monks in Russia.” I understood that it was no accident that she said this, because there were other ascetics at that time; but Mother emphasized precisely Vladyka Pitirim. I asked her: “Mother, when you are gone, should I go to Vladyka Pitirim, and he’ll be my elder?” To which she smiled and replied: “Yes, yes. You want me to die faster so can you go to Vladyka.” I thought that if Mother didn’t have to say this, she wouldn’t have said anything about Vladyka Pitirim, or she would’ve said I didn’t need to go to him; but apparently Mother wanted and knew that I needed to meet this outstanding hierarch and man of prayer.

Mother Maria departed from this world in 1978; so I, of course, was looking for a spiritual guide, and all my dreams were directed towards meeting and getting to know Metropolitan Pitirim. At that time, I wanted to go study in Russia, in the Moscow Theological Academy, although they told me I could write a PhD thesis there but not get a foundational theological education. So I finished the theological academy in Sophia via correspondence.

—When did you first come to Moscow?

—I went to Moscow three times on regular tourist trips when I was still studying in Bulgaria. I met Vladyka Pitirim there when I visited the Publishing Department of the Moscow Patriarchate. Vladyka and I found a common language, and we became friends. And when I graduated from the theological academy in Sophia, our Synod sent me to the Moscow Theological Academy as a professorial fellow to write a PhD thesis on the “Characteristic Features of the Nineteenth-Century Russian Ascetics of Piety.”

My stay at the Moscow Theological Academy gave me wonderful, happy years, where I could gather spiritual riches by reading and writing my paper. Reading and writing about the Russian ascetics was healing for my soul.

After writing and defending my thesis at the Moscow Theological Academy in 1986, I received the order from the Synod of the Bulgarian Church to become the rector of the Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos in Gonchary in Moscow—the representation church of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, where I remained until 1991. In 1991, they blessed me to return to Bulgaria and I was appointed as protosingel (secretary of a bishop or diocese) of His Holiness Patriarch Maxim.

—They say it was a difficult time for the Bulgarian Church.

—Yes, a schism was beginning at that time in the Bulgarian Church, and there was a serious confrontation in Sophia. No blood was spilled, of course, but Church property and funds were actively seized. The authorities were on the side of the schismatics. It was a very difficult time. We helped the Patriarch and fervently prayed for him.

In 1998, the Synod appointed me to be vicar bishop to His Holiness Patriarch Maxim, and I was soon consecrated at Rila Monastery. In 2000 Metropolitan Gregory of Lovech reposed, and after the elections I was appointed to that See. I arrived there on February 3, 2001.

Vladyka Pitirim and I saw each other often enough in Bulgaria while he was still alive. I always consulted with him and asked him about many things, and I always received succinct spiritual answers. I must say that Vladyka Pitirim was clairvoyant. He foretold many things to me, but tried to do it very carefully, not directly. Vladyka was a wise man, but very modest, always hiding his abilities and spirituality, but expressing Russian culture, intelligence, and beauty. He was very worried for Russia and grieved for the destruction of its moral foundations and traditions. Vladyka tried to help everyone who was in need, always sparing time for people. Not everyone understood him—only those who truly desired to receive his help and support. Metropolitan Pitirim was a true ascetic of faith and piety.

—Tell us about Vladyka Pitirim as a hierarch, about the services he celebrated. They say he was a very focused, responsible, aristocratic man.

—Vladyka Pitirim was an example for me in absolutely everything. He served quite often, and always very grandly and beautifully, with concentration, fully immersed in the meaning of the services and with zeal for fulfilling the Typikon. While on official trips, Vladyka always found an opportunity to serve the Liturgy. His reverent care and prayer for his flock were always evident.

Vladyka Pitirim took every opportunity to help people in need. For example, if we were on a train, he tried to talk with people on various topics, carefully switching to spiritual topics. Many people knew Vladyka Pitirim because of this and always warmly remembered him.

Vladyka was very delicate and polite when talking with people. He was well aware that you couldn’t immediately start talking about faith, about Confession, about Communion with everyone, but he tried just to speak warmly, carefully, without any pressure or attack, just to say something about the Church and how necessary it is to live in it.

He brought many people to faith—even members of the Communist Party I think, because according to him, there were believers there. Vladyka really loved to visit the parishes of his diocese, which were mostly rural and poor. Sometimes they didn’t have the proper conditions for celebrating a hierarchical service. It was impossible to get there by car. There were villages where the local elders said no bishop had been since the time of the Tsar. Vladyka would visit the village children, speak with them, and help them financially—especially schools, since that’s where children gain knowledge and are cultivated in culture. Once Vladyka bought some small horses for the children so they could ride them and enjoy their childhood. I remember how soldiers would approach him after the services, because they got such joy and inspiration from talking with Vladyka—especially in the difficult 1990s…

He paid no mind to fatigue, but tried to give everyone his time and attention. I have the warmest memories of him as a true hierarch, a monk, a true Russian man, in whom all the virtues of the Russian man were combined. Vladyka was a true representative of the old, pre-revolutionary Russia. For me, he was and will remain an example for the rest of my life.

—From 1986 to 1991, you served in Moscow as the rector of the Bulgarian representation church. How do you remember Moscow Church life in that rather difficult time?

—From my time at the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, I remember the piety and responsible attitude the people had towards the services. Many people would come early before the service to focus and take their spot. The majority of parishioners would stay at the church until the end, even for akathists. They prayed and attentively listened to the texts of the services. I observed the same at our representation church when I was the rector there. There were very few active churches at that time, and the people cherished the chance to gather for joint prayer. No one allowed themselves to condemn the priests, the monks. Even if the clergy made some kind of mistake or had some shortcomings, everyone treated them with understanding and kindness; with respect, gratitude, and reverence.

They really loved Bulgarians in Moscow at that time, and I could feel the love and respect of the Muscovites. There was respect and understanding, spiritual love and reverence between people. Many people would confess and commune, especially during the fasts. The faith of the people was truly confessional, because they had to endure hardships and oppressions of various kinds. They spared no time or effort for the sake of the Lord and communion with Him. After Perestroika the authorities’ attitude towards the Church improved, and they gradually started helping. More people started coming to church, although the life and well-being of society had deteriorated. Difficulties in the life of the state gradually appeared. But, by the grace of God, they started opening churches, which became a refuge and comfort for the people.