The south of England is the warmest and sunniest part of the United Kingdom. Though mostly low-lying, it has some significant areas of rolling hills. Its main natural attractions are the coastline (bordering the English Channel that separates it from northern France) stretching hundreds of miles, the famous beautiful white cliffs of Kent, Dorset and Sussex—notably the “Seven Sisters” chalk cliffs—the Chilterns, the New Forest, the North and South Downs National Parks, the Thames Valley, along with historic castles, palaces, stately homes and gardens. The industries of the region are rich and highly developed, as is education, with the world-renowned Oxford University among its gems.

In the “Age of the Saints,” Kent was mainly inhabited by the Jutes, what is now East and West Sussex comprised the kingdom of Sussex (“of the South Saxons”), while the rest of the region mainly belonged to the kingdom of Wessex (“of the West Saxons”), which subsequently became dominant and annexed Sussex after the battle of Ellandun in 827. The southeast of England played an important role in the Christianization of England as this was the starting point of the mission of St. Augustine, sent by the holy Pope Gregory the Dialogist (the Great) from Rome. The first Christians had appeared in the south of England with the Romans1 and merchants in the first century A.D. But the development of the Orthodox faith did not begin until the early seventh century.

Though very far away from the north with its strong Celtic (Irish) influences, the Irish Orthodox tradition penetrated this part of the country as well. Among those that lived and labored here were such celebrated saints as Aldhelm of Sherborne; Alfred the Great; Alphege, Augustine, Dunstan and Theodore of Canterbury; Birinus of Dorchester; Botolph2; Eanswythe of Folkestone; Edith of Wilton; Edward the Martyr; Erconwald of London; Ethelwold and Swithin of Winchester; Frideswide of Oxford; Mildred of Thanet; and Wilfrid, “the Apostle of Sussex.” The region has a wealth of ancient holy shrines, such as Canterbury, Chichester, Oxford, Rochester, Salisbury, St. Paul’s and Southwark (both in London) and Winchester Cathedrals; Abingdon, Battle, Beaulieu, Christchurch, Cerne, Dorchester-on-Thames, Lacock, Malmesbury, Minster-in-Thanet, Reading, Romsey, Shaftesbury, Sherborne and Westminster (London) Abbeys. A number of Saxon churches are still intact. Let’s talk about several locally venerated early saints of the south.

Venerable Cuthburga and Cwenburga, Abbesses of Wemborne

Commemorated: August 31 / September 13

Detail of St. Cuthburga window at Wimborne Minster, Dorset (kindly provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wemborne Minster)

Detail of St. Cuthburga window at Wimborne Minster, Dorset (kindly provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wemborne Minster)

St. Cuthburga (Cuthburgh), who reposed in about 725 (718 is also given), is venerated as the foundress of the famous double monastery in Wemborne in what is now Dorset, which then was part of the kingdom of Wessex. This monastery served as an extremely important center that trained many missionaries who later travelled to the German lands to evangelize the local inhabitants and build monasteries. The most striking aspect of this story is that most of those heroic missionaries were saintly women, highly cultured and educated, and with brave spirits, who did not fear the pagans in Germany but would fell trees, build churches and monastery complexes, were in contact with local populaces, educating, instructing them in the faith and teaching them various skills. Some of those women wrote manuscripts, excelled in crafts and corresponded with the great enlighteners of the age, such as St. Boniface, the Apostle of Germany.

Her life is related in two manuscripts of the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. St. Cuthburga, the future first abbess of Wemborne, was a daughter of Cenred, a sub-king of Wessex, and a sister of the holy King Ina (Ine) of Wessex, a pious ruler who ruled from 688–726 and refounded and endowed Glastonbury Monastery, issued a Code of Laws and later abdicated and ended his days in Rome. St. Cuthburga was married to Aldfrith, King of Northumbria (ruled 685–704), who was noted for his learning, support for the Church and his peaceful reign. Dynastic marriages were important and common in that stage of English history. According to the most popular version, after several years of marriage, St. Cuthburga, who had always longed for the monastic life, separated from Aldfrith by mutual consent and became a nun at the double Monastery in Barking in Essex, founded by the Holy Hierarch Erconwald of London for his sister St. Ethelburgh, its first abbess.

Nowadays Barking is a suburb of East London. St. Cuthburga was taught and nurtured at Barking by its second abbess St. Hildelith, who ruled both communities in Barking for many years and was esteemed for her wisdom and culture. Cuthburga’s saintly sister Cwenburga lived with her in Barking. Now well-prepared and experienced, after 705 St. Cuthburga left Barking with her sister and founded a double monastery in honor of the Mother of God in Wemborne, becoming its first superior. As was the case with other double monasteries, it was predominantly a convent and ruled by an abbess rather than an abbot. Her biographers describe St. Cuthburga as very austere to herself, but kind to others and assiduous in fasting, prayer and spiritual life. Few facts from St. Cuthburga’s abbacy survive, but we can judge it by its accomplishments, for Wemborne produced a host of saintly women, both abbesses and missionaries to foreign lands. Before her repose, St. Cuthburga fell seriously ill, and while the sisters were praying for her recovery, she revealed to them that it was the will of God for her to die. Her relics were buried on the north side of the presbytery, and was later transferred to the east end of the High Altar. Many miracles occurred at her tomb: The lame regained the ability to walk, sight was restored to the blind and hearing to the deaf. Her name can be found in a late Saxon litany.

St. Aldhelm of Sherborne addressed his De Laude Virginitatis (the prose De Virginitate), a Latin treatise on virginity, to the nuns of Barking (before 705), with St. Cuthburga among them. St. Cuthburga’s veneration was not limited to Wemborne: in the late medieval period she was venerated at Thelsford Priory in Warwickshire in central England, where a commissioner of Henry VIII during the Reformation came across a devotional image of the “Maiden Cuthburga” in 1538. It is unknown whether St. Cuthburga and Aldfrith had children, and some historians conjecture that King Osred of Northumbria (705-716), Aldfrith’s son, was born by the saint, though his mother may have been Aldfrith’s next wife. At least St. Cuthburga did not act as regent after Aldfrith’s death when his son was eight. Our saint had a brother named Ingild who was an ancestor of St. Alfred the Great. St. Cuthburga’s shrine was destroyed during the Reformation, and the same fate befell the silver reliquary with her head.

St. Cwenburga (Quenburgh, Coenburga), who reposed in about 735, was St. Cuthburga’s sister. Few facts about her life are known. She lived at Barking Monastery with St. Cuthburga and later left it to found Wemborne Monastery together with her. After St. Cuthburga’s repose, St. Cwenburga succeeded her as the second abbess. Ninth-century hagiographers wrote that there had been 500 nuns at Wemborne Monastery at that time and monastic life flourished. St. Cwenburga’s name can be found in two late Saxon litanies. The names of both holy sisters can be found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s entry for the year 718.

One of the successors of Sts. Cuthburga and Cwenburga was St. Tetta, an illustrious abbess of Wemborne († c. 772; feast: September 28), who at the request of St. Boniface of Fulda helped him in his apostolate in Germany by sending experienced nuns as helpers and future abbesses on the Continent. The fact that St. Boniface turned to an abbess and not to a bishop for help to strengthen the Church in central Europe speaks volumes!

Among those holy women missionaries let us mention:

—St. Agatha († c. 790; feast: December 12), a disciple of St. Lioba who assisted St. Boniface in his work in Germany

—St. Gunthildis († c. 748; feast: December 8) who became abbess of a convent in Thuringia in Germany

—St. Lioba (Liobgytha; † c. 781; feast: September 28)—her ninth-century Life is intact and very much worth reading. A relative and beloved disciple of St. Boniface, she moved with a group of thirty nuns to the German lands, where she became abbess of Tauberbischofsheim and supervised other monasteries. She was greatly esteemed for her love, wisdom and other exceptional qualities, and her activities played a significant role in the conversion of Germany. her advice was sought by both Church and State officials. Before her repose she retired to Schornsheim. Her main set of relics is in Fulda.

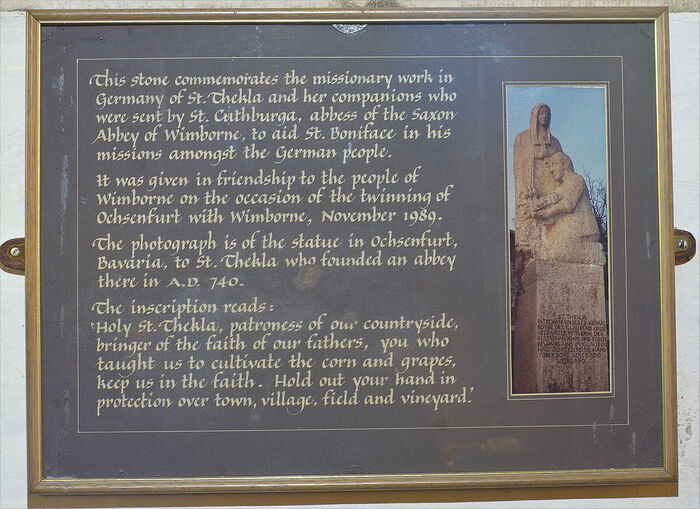

—St. Thecla († c. 790; feast: October 15) moved with her relative St. Lioba to Germany, where she became the first abbess of Ochsenfürt and then of Kitzingen in Bavaria. Her relics at Kitzingen were greatly venerated but scattered during the Peasants’ War in 1524-25.

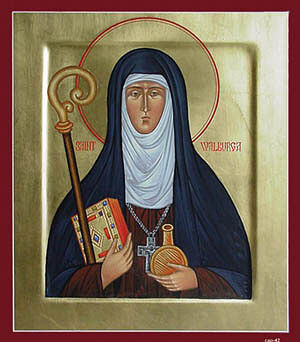

An icon of St. Walburga —St. Walburga (Walburgh; † c. 779; feast: February 25) was the sister of two great missionaries Sts. Willibald and Winibald and daughter of St. Richard of Wessex. She served as abbess of Heidenheim in Germany (the only known double monastery there). Known for her good nature, prudence, gentleness, skill in medicine and a high level of culture, she wrote St. Winibald’s Life and an account of his travels in the Holy Land in Latin after his repose. Her relics were translated to Eichstätt and they still exude myrrh with many reports of healing. Portions of her relics were translated to the Rhineland, Flanders and various places in France. Her name is associated with a number of folk customs, and artists would depict her for many centuries.

An icon of St. Walburga —St. Walburga (Walburgh; † c. 779; feast: February 25) was the sister of two great missionaries Sts. Willibald and Winibald and daughter of St. Richard of Wessex. She served as abbess of Heidenheim in Germany (the only known double monastery there). Known for her good nature, prudence, gentleness, skill in medicine and a high level of culture, she wrote St. Winibald’s Life and an account of his travels in the Holy Land in Latin after his repose. Her relics were translated to Eichstätt and they still exude myrrh with many reports of healing. Portions of her relics were translated to the Rhineland, Flanders and various places in France. Her name is associated with a number of folk customs, and artists would depict her for many centuries.

The Life of St. Lioba of Bischofsheim3, written in about 836 by Hieromonk Rudolf of Fulda, has the following description of Wemborne Monastery:

“In the island of Britain, which is inhabited by the English nation, there is a place called Wimbourne, which may be translated ‘Winestream’. It received this name from the clearness and sweetness of the water there. In olden times the kings of that nation had built two monasteries in the place, one for men, the other for women, both surrounded by strong and lofty walls and provided with all the necessities that prudence could devise. From the beginning of the foundation, the rule firmly laid down for both was that no entrance should be allowed to a person of the other sex. No woman was permitted to go into the men's community, nor was any man allowed into the women’s, except in the case of priests who had to celebrate Mass in their churches. Any woman who wished to renounce the world and enter the cloister did so on the understanding that she would never leave it. She could only come out if there was a reasonable cause and some great advantage accrued to the monastery. When it was necessary to conduct the business of the monastery and to send for something outside, the superior of the community spoke through a window and only from there did she make decisions and arrange what was needed. It was over this monastery, in succession to several other abbesses and spiritual mistresses, that a holy virgin named Tetta was placed in authority, a woman of noble family (for she was a sister of the king), but more noble in her conduct and good qualities. Over both the monasteries she ruled with consummate prudence and discretion. She gave instruction by deed rather than by words, and whenever she said that a certain course of action was harmful to the salvation of souls she showed by her own conduct that it was to be shunned. She maintained discipline with such circumspection that she would never allow her nuns to approach clerics. She was so anxious that the nuns, in whose company she always remained, should be cut off from the company of men that she denied entrance into the community not merely to laymen and clerics but even to bishops. There are many instances of the virtues of this woman which the virgin Lioba, her disciple, used to recall with pleasure when she told her reminiscences.”

Rudolf mentioned two miracles of St. Tetta. First, after the death of an imprudent prioress, who had provoked resentment towards herself in the sisterhood, the earth heaped over her grave sank and the ground subsided, showing that the Lord punished her. While some sisters started rejoicing, St. Tetta ordered them to forgive her, keep strict fast and pray for her repose for three days, and when on the third day they were all praying in church, the ground on the prioress’ grave miraculously rose, and St. Tetta saw in spirit that the prioress was forgiven by God. In another instance, the nun who took care of the chapel lost the church keys in the darkness and could not find them. St. Tetta knew that it was the work of the devil. Gathering in another building for Matins, she asked the nuns to join her in earnest prayer—and soon there appeared a dead fox by the chapel with the lost keys in its mouth.

Wemborne Monastery was not only a training ground for missionaries but also a burial place for royalty, and later, a house of secular canons. Sometime after St. Cwenburga’s death there were as many as three monastic communities in Wemborne. The monastery lasted till 1013, when it was destroyed by the Danes. In 1043, King Edward the Confessor founded a college of secular canons on the site of the monastery. In 1318 King Edward II made this church a royal peculiar or stavropegia, a prestigious status which meant that the church answered directly to the monarch and not to its diocese. The Minster choir used to wear scarlet robes until 1846.

Ethelred I, King of Wessex (865-871) and St. Alfred the Great’s older brother, was buried in the Wemborne Monastery church after he died, aged about twenty-six.

Wemborne Minster SE corner, Dorset (kindly provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wimborne Minster)

Wemborne Minster SE corner, Dorset (kindly provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wimborne Minster)

The market town of Wemborne Minster in Dorset has a population of just over 15,000. It stands at the confluence of the Rivers Stour and Allen and has many buildings dating from the fifteenth to seventeenth century. Its pride is the large ancient Anglican church known as “Wemborne Minster Church,” dedicated to St. Cuthburga. Built of multicolored stone, this church is one of the finest in southern England and retains some Saxon elements. Most of the current edifice was built by the Normans between 1120 and 1180 and restored in the Victorian era. It has two towers: the older central one and the later one at the west end. The Minster receives thousands of visitors every year. Among its internal features of interest to pilgrims let us mention:

The Saxon chest under the Courtenay window at Wimborne Minster, Dorset (provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wemborne Minster)

The Saxon chest under the Courtenay window at Wimborne Minster, Dorset (provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wemborne Minster)

a. A late Saxon reliquary chest carved from a single block of oak. It is empty, but formerly it housed relics. All the relics would have been removed and destroyed under Henry VIII. Before then the Minster had even kept a particle of the True Cross and tiny fragments of the Manger and the Holy Shroud.

St. Thecla Stone in the crypt of Wimborne Minster, Dorset (kindly provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wemborne Minster)

St. Thecla Stone in the crypt of Wimborne Minster, Dorset (kindly provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wemborne Minster)

b. A stone sculpture in the crypt, known as the “St. Thecla Stone,” depicting St. Thecla. The stone was presented to the Minster when representatives from Wemborne visited Ochsenfürt, Germany, for the signing of the Twinning (between the two towns) documents in November 1988. The stone was carved by an Ochsenfürt mason. There is a picture under the stone which shows a statue carved by the same mason. That stone is located in a vineyard in Ochsenfürt and is where her Abbey was situated.

Inscription of St. Thecla stone at Wimborne Minster (kindly provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wimborne Minster)

Inscription of St. Thecla stone at Wimborne Minster (kindly provided by Gordon Edgar, The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga, Wimborne Minster)

The inscription reads: “Holy St. Thecla, patroness of our countryside, bringer of the faith of our fathers, you who taught us to cultivate the corn and grapes, keep us in the faith. Hold out your hand in protection over town, village, field and vineyard.”

The High Altar and Ethelred I's brass at the Wemborne Minster Church, Dorset (photo from Wikipedia)

The High Altar and Ethelred I's brass at the Wemborne Minster Church, Dorset (photo from Wikipedia)

c. Ethelred I’s brass to the left of the High Altar.

The fourteenth-century astronomical clock at Wemborne Minster, Dorset (photo from Geograph.org.uk)

The fourteenth-century astronomical clock at Wemborne Minster, Dorset (photo from Geograph.org.uk)

d. The famous fourteenth-century astronomical clock where the earth is shown in the center of the solar system. Made by Monk Peter Lightfoot of Glastonbury, it is situated on the wall in the baptistery and was recently repainted. Similar clocks can be found in Exeter, Salisbury and Wells Cathedrals.

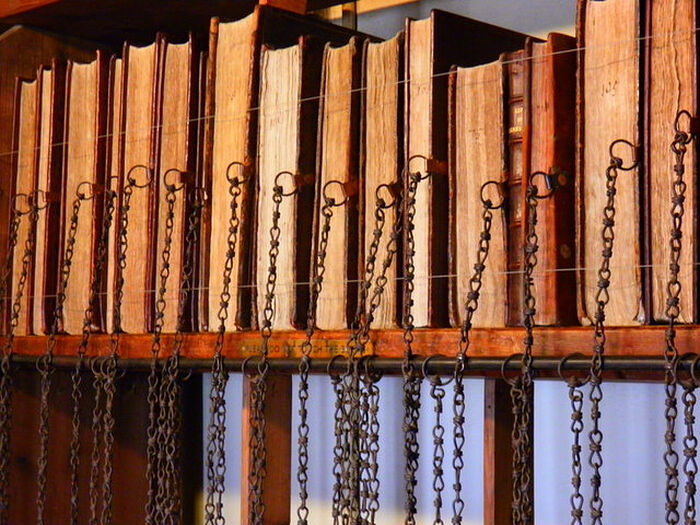

The Chained Library of the Wemborne Minster Church, Dorset (photo - Wikimedia Commons)

The Chained Library of the Wemborne Minster Church, Dorset (photo - Wikimedia Commons)

e. One of the four medieval “chained libraries” in existence in the world. It can be found above the choir vestry. It houses over 400 books, along with a collection of church music, and is the second largest in the country.

f. A twelfth-century stone corbel of the Prophet Moses with horns and a beard to the right of the High Altar.

g. A Victorian stained-glass window depicting St. Cuthburga in the Minster’s giftshop, formerly the Consistory Court which was an important location within the Minster and was not demolished.

The 'Quarter Jack' painted statue on the west tower of Wemborne Minster Church, Dorset (photo - Wikimedia Commons)

The 'Quarter Jack' painted statue on the west tower of Wemborne Minster Church, Dorset (photo - Wikimedia Commons)

h. The painted statue of a grenadier guard called “Quarter Jack,” set in the exterior of the later tower. It strikes the quarter-hours on a pair of small bells.

i. Medieval wall paintings in the north transept, the oldest of which is the thirteenth century.

Some believe that St. Cuthburga’s relics survived and lie somewhere under the floor. She had previously been buried under what is now the Choir near the steps up to the High Altar. When the wealthy Bankes family (the landowners who possessed much of east Dorset) wanted to have their burial vault constructed under the choir, the supposed grave of St. Cuthburga was “inconveniently in their way” and had to be moved (presumably underneath the crossing in front of the lectern and approximately where the pulpit was located). Even if the holy princess, queen, nun and abbess lies within this church, her grave is unmarked.

The town’s faithful commemorate St. Lioba annually at the end of September: the service alternates between the Minster Church and the RC church.

Thomas Hardy lived in Wemborne Minster for two years and it was there that he wrote his novels Two on a Tower and A Pair of Blue Eyes.

Saint Dicul of Bosham

Commemorated: April 18 / May 1

The Holy Trinity Church in Bosham, West Sussex (photo from Wikipedia)

The Holy Trinity Church in Bosham, West Sussex (photo from Wikipedia)

St. Dicul (Dicuill, Deicola) was Irish and lived in the second half of the seventh century. Though obscure, his legacy in West Sussex is still alive. He is one of the Irishmen who in the seventh century emigrated to England to preach Christ to its largely pagan kingdoms. While such Irish saints as Aidan of Lindisfarne and Fursey of Burgh Castle played a significant role in the conversion of the English, St. Dicul remained uninfluential and never attempted to organize a large-scale mission. Yet the glorious Saxon church in Bosham in West Sussex founded by him is a true gem visited by pilgrims.

The holy Abbot Dicul of Bosham with a tiny community of five or six monks was discovered by St. Wilfrid when he was evangelizing this kingdom—the last of the early English kingdoms to embrace Orthodoxy—between 681 and 686.4 St. Wilfrid built a church in Bosham too, but no trace of it survives. It was not surprising to find wandering Irish monks outside their homeland as self-imposed exile for Christ’s sake was an Irish ascetic tradition. Besides, the south of England served as an overland route for the Irish travelling to the Continent.

As for St. Dicul, some scholars believe that he first preached in Norfolk in East Anglia and was associated with the mission of St. Fursey, who founded a monastery at Burgh Castle in Norfolk. (The village of Dickleburgh in Norfolk may well be named after St. Dicul as he might briefly have lived there). After the pagan King Penda attacked East Anglia and St. Fursey with his companions had to move to the continent, St. Dicul may have travelled south to Sussex and founded Bosham Monastery in about 670. Among his companions at Bosham may have been the holy brothers Botolph and Adolph, who also had to flee from East Anglia for a time. The year and date of St. Dicul’s death are unknown. According to one version, his grave was at Delgany in County Wicklow in Ireland.

The name of St. Dicul occurs in several early martyrologies, which indicates the authenticity of this saint. Today the only place of his veneration is Bosham.

The chancel arch of the Holy Trinity Church in Bosham, West Sussex

The chancel arch of the Holy Trinity Church in Bosham, West Sussex

The Saxon church in the idyllic coastal village of Bosham (two miles away from Chichester at the foot of the South Downs National Park), founded by St. Dicul, is dedicated to the Holy Trinity and is used as an Anglican parish church. This imposing edifice is one of the most impressive early English churches of the UK. The original church and monastery founded by St. Dicul were wooden and smaller, and the present structure of rubble is mainly late Saxon, with many Norman additions.

The crypt chapel inside the Holy Trinity Church, Bosham, West Sussex (photo - Wikimedia Commons)

The crypt chapel inside the Holy Trinity Church, Bosham, West Sussex (photo - Wikimedia Commons)

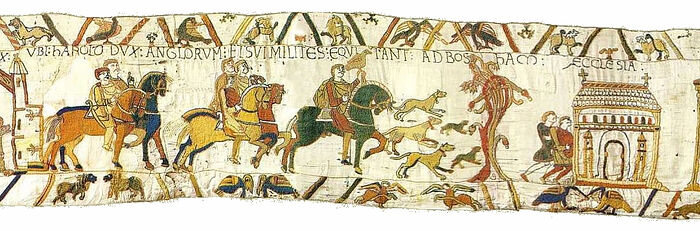

Inside the church an atmosphere of holiness still reigns. The early lofty and splendidly carved chancel arch is one of the most remarkable features. It appears (with the church itself) in the famous Bayeux Tapestry: an intact fine embroidered cloth, about 230 feet long, illustrating in seventy scenes events leading up to the Norman Conquest, woven between 1066 and 1077 in England for the Bishop of Bayeux in Normandy (kept at the Bayeux Museum in France, and there is a replica at Reading Museum in the UK). The chancel was built in three stages: Saxon, Norman and Early English Gothic. The intact fourteenth-century crypt with the memorial All Hallows’ Chapel above it is a place for prayer and meditation on the labors of the early pioneers of Orthodoxy Sts. Dicul and Wilfrid (they were proponents of the “Celtic” and the “Roman” traditions respectively, different but not conflicting). The font is of the late twelfth century. Of the four stages of the tower, three are Saxon and one is Norman. The church is famous for its musical traditions.

In 1121, the Bishop of Exeter set up a college in Bosham with the dean and secular canons, making it dependent on his diocese (though Bosham has always been in the Diocese of Chichester). For over 700 years after that, the church chancel was used as a chapel by the college, and its nave as a parish church, causing controversy. In 1840, the patronage of the whole church finally passed to the Diocese of Chichester.

King Harold and his retinue are riding to Bosham before his ill-fated journey to Normandy, a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry (photo from Wikipedia)

King Harold and his retinue are riding to Bosham before his ill-fated journey to Normandy, a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry (photo from Wikipedia)

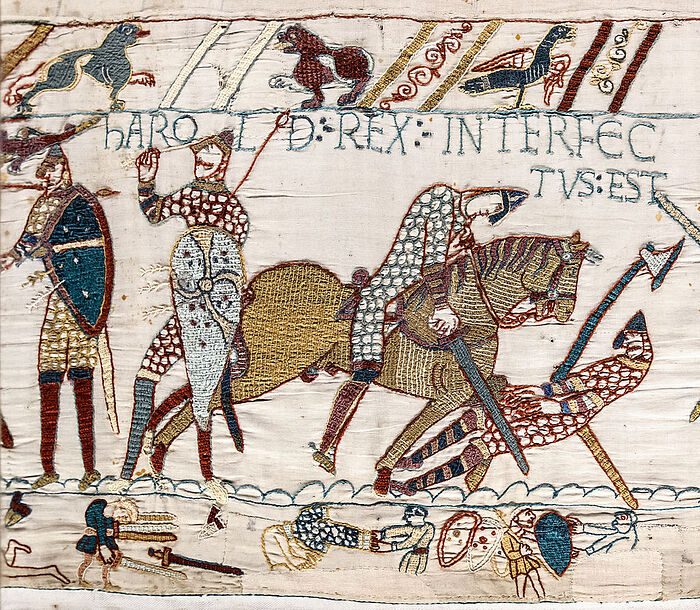

The Battle of Hastings shown on the Bayeux Tapestry (photo from Wikipedia)

The Battle of Hastings shown on the Bayeux Tapestry (photo from Wikipedia)

According to one version, Harold II Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon King of England, is buried in this church. However, this claim is disputed by Waltham Abbey in Essex. Harold ruled the country for nine months after Edward the Confessor’s death in the early 1066, but he was faced with two invasions during his short reign. He resisted his half-brother Tostig and the Norse king Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, but was killed by an arrow to the eye and his army was defeated by William I the Conqueror at the decisive Battle of Hastings (now in East Sussex). Interestingly, his daughter, Princess Gytha, soon moved to Kievan Rus’ and married Prince Vladimir II Monomakh, becoming a member of the Russian Rurikid Dynasty. Among their children were the holy Grand Prince Mstislav I of Kiev, Izyaslav, Svyatoslav, Grand Prince Yaropolk II of Kiev, Grand Prince Vyacheslav I of Kiev and possibly Grand Prince Yuri Dolgorukiy of Kiev—the founder of Moscow. This direct link of the pre-Norman (i.e. Orthodox) English Wessex Dynasty with the Rurikids is spiritually significant. Earl Godwin of Wessex, Harold’s father, in the first half of the eleventh century amassed his wealth mainly in Sussex, including the manor of Bosham, so the preservation of the Saxon church may be attributed to him.

King Harold's death depicted at the Bayeux Tapestry (photo from Wikipedia)

King Harold's death depicted at the Bayeux Tapestry (photo from Wikipedia)

Another tradition is connected with Bosham’s natural harbor. It may have been the scene where the converted Danish King Canute of England (ruled 1017–1035) sat on his throne in front of the sea and demonstrated to his fawning courtiers his inability to stop the rising tide, showing that God is mightier than anyone else.

Given that some parts of the Bosham church look Roman, and a number of Roman buildings and artefacts were found in the area, and the famous Roman palace at Fishbourne is very close, some suggest that the Holy Trinity Church is a former Roman basilica, but there is lack of archeological evidence to confirm this. Legend has it that the Roman Emperor Vespasian (69-79 A.D.) maintained a residence in Bosham, but again there is no evidence to support this theory.