It’s amazing how Dostoevsky’s presentiment predicted the Russian revolution.

An advertisement for the 2014 film, Demons

An advertisement for the 2014 film, Demons

Murder of the student Ivanov

In July 1871, St. Petersburg and all Russia were shocked. A court trial had been completed against the organizers and participants in the murder of a student of the Petrovsky (now Timiryazevsky) agricultural academy in Moscow, Ivan Ivanov. His corpse with traces of trauma and bullet wounds to the head was discovered by a security guard under the ice of a pond in the academy park on November 25, 1869.

During the court proceedings, horrifying circumstances came to light. Behind the crime was a terrorist group called “The People’s Revenge”, the goal of which was mass terror against government officials, the ruling classes, and their—according to the group’s ideology—abettors. Ivanov’s “guilt” before the organization consisted in insubordination to the group’s leader. The murderers received various sentences to hard labor, since the leader himself, Sergei Nechayev, had fled the country.

Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky became interested in this story as soon as the investigation had begun. He had learned about it before the court proceedings, not only from the newspapers but also from the brother of the wife of one of the academy’s students, who was personally acquainted with certain of those who were involved in the affair. What Dostoevsky read and heard inspired him to sit down and write a new novel—“Demons”. The beginning of the novel was published as soon as 1871 in the periodical, Russky Vestnik.

Communism: freedom only for the chosen, slavery for the rest

“One percent of the population will receive personal freedom and unlimited rights over the other ninety-nine percent. These are destined to lose their own personalities and became a kind of herd, and through unlimited submission they are to achieve rebirth and primordial innocence—although of course they will labor.”

This is the program for a communist paradise that was voiced by one of the characters in Demons, Peter Verkhovensky, at a meeting of the like-minded “progressive intelligentsia” in one provincial town. Strangely this “ideal” was not met with repugnance, because considering their “correct convictions”, each one there was counting on his own inclusion in that one percent, which would be granted the right to punish or pardon, and lead mankind to a “bright future”.

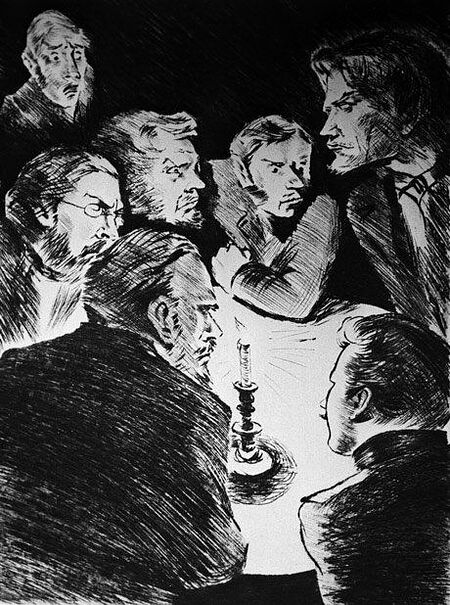

Illustration to Feodor Dostoevsky’s novel, Demons. “The Five”, 1935.

Illustration to Feodor Dostoevsky’s novel, Demons. “The Five”, 1935.

Both then and much later radical circles accused Dostoevsky of painting a caricature of revolutionaries, of taking for his model the most extreme and odious members of this milieux. However, as the Polish-American historian Adam Ulam notes concerning the above-quoted prophecy, “today this picture is no longer funny”. In fact, attempts to create a communist utopia in the twentieth century in Russia, China, Cambodia, and other countries unfailingly turned into the right of the privileged minority to limitlessly decide the lives and deaths of the vast majority for the sake of that majority’s imaginary happiness (that would come after several generations).

Through his great giftedness Dostoevsky saw into the future to which the demons of the revolution would lead Russia, with the allowance and approval of “liberal society”, against whose conformist position the book was mainly aimed.

Dostoevsky’s gloomy prophecy fell on deaf ears. It was precisely the intelligentsia, until 1917 exultant over the anarchist bombers and expropriators in their struggle against the “hated monarch”, that became the first victims of those demons that had clawed their way into a position of unlimited power.