A church in the name of St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco was recenly consecrated in Belgium. In honor of this joyous occasion, we remember the life of this saint who served there.

On October 23, a church was consecrated in the name of St. John (Maximovitch) of Shanghai and San Francisco in the Belgian city of Antwerp. The consecration was celebrated by Archbishop Simon of Brussels and Belgium. The event attracted public attention. The ceremony was attended by the representatives of various churches, city administration officials, and the Russian ambassador to Belgium, Alexander Tokovinin.

An icon of St. John was painted in Russia especially for the new church, in which a particle of his relics, brought from San Francisco, was mounted. It was there that the Holy Hierarch labored in the final years of his life. And there, in the Holy Virgin-Joy of All Who Sorrow Cathedral, they preserve his relics.

As Archbishop Simon said, the consecration of the church was already postponed several times due to the coronavirus pandemic, but then they decided that it couldn’t be put off anymore. According to Vladyka, the decision to consecrate the church in the name of St. John was made by the faithful themselves. A survey was conducted in the diocese about a year ago, and the absolute majority supported the idea of consecrating the altar in honor of St. John.

The choice of patron saint was no accident. Seventy years ago, in 1951, Vladyka John was appointed Archbishop of Paris and Western Europe, and in 1952—Archbishop of Brussels and Western Europe. That year he also became the rector of the Memorial Church of St. Job the Much-Suffering in Brussels, where he served for twelve years. Having his official residence in Versailles, near Paris, the Archbishop often traveled to Brussels and served in the Church of the Resurrection of Christ or in the memorial church. During his stays in Belgium, he would stay in an annex to the Church of St. Job, on the second floor, right under the bell tower. They still keep his episcopal staff on the solea in the church, bringing it out to the center of the church on his feast days.

The keeper of his memory

Dmitry Alexeevich Gering, civil engineer, Doctor of Theology

Dmitry Alexeevich Gering, civil engineer, Doctor of Theology

The living memory of Vladyka John is represented today by Dmitry Alexeevich Gering, a parishioner of the Church of St. Job and a civil engineer and Doctor of Theology. In his childhood in the 1950s, he served in the altar with Archbishop John whenever he would go to Belgium. Dmitry told us about the most memorable moments from his time with Vladyka.

Memorial Church of St. Job the Much-Suffering When the Archbishop first went to Belgium, he immediately noticed some abbreviations in the services. He himself served the Liturgy in full, without any abbreviations. The service was especially prolonged because during the Cherubic Hymn, Vladyka would commemorate all of his benefactors and donors. “Of course for us boys, it was hard to endure the longer services,” Dmitry recalls. “Vladyka wanted the acolytes to leave the church only once he had finished consuming the Holy Gifts. Not before.”

Memorial Church of St. Job the Much-Suffering When the Archbishop first went to Belgium, he immediately noticed some abbreviations in the services. He himself served the Liturgy in full, without any abbreviations. The service was especially prolonged because during the Cherubic Hymn, Vladyka would commemorate all of his benefactors and donors. “Of course for us boys, it was hard to endure the longer services,” Dmitry recalls. “Vladyka wanted the acolytes to leave the church only once he had finished consuming the Holy Gifts. Not before.”

At the All-Night Vigil in the Church of St. Job, during the Six Psalms, Vladyka John would rest on the chair that stood on the solea. “Sometimes you could see that Vladyka was nodding off a little. But if someone read something incorrectly or put the accent on the wrong spot, he would immediately raise his head,” says Dmitry with a smile.

He remembers Vladyka John as a very kind and hospitable man. “My father was the church warden. Vladyka John was close with him and came to our house quite often. Sometimes, when my father had some questions, he would go see Vladyka John and discuss them with him. Vladyka would always say to my father: ‘Sit, eat,’ although he himself ate only once a day.”

“He didn’t play bishop”

According to Dmitry, Vladyka John always acted very naturally. “He didn’t play bishop.” There was no “episcopal grandeur” in him.

He was a small, hunched, unattractive man. When he served—which he did every day if possible—he served as a priest, not according to the episcopal rite. He would have his phelonion on, but instead of his omophorion he wore a white woolen scarf with crosses, and instead of a miter—a cap with crosses. And when Vladyka John spoke, it was hard to understand him. He didn’t enunciate very well and he mixed Russian and Church Slavonic words.

Attitudes towards Archbishop John varied. Some respected him greatly, while others couldn’t understand his untidiness and his love for long services. They recall how Vladyka often went about barefoot or in sandals. Some didn’t like that. Many who didn’t know him personally even called him “John the Dirty.”

A gift from a saint

And Archbishop John was simple not only in his attire, but also in his speech. Dmitry recalls how Vladyka never forgot to send him and his brother greetings cards on their names’ days. Dmitry still has these cards. Vladyka would very carefully write his greetings on them, and would very carefully—so carefully that you could see how his hand must have been shaking—draw a cross on them. Dmitry and his brother, who were just boys then, also wrote to Archbishop John. “When we sent him cards for Pascha, we addressed him as: ‘Dear Vladyka.’ Nothing more—no ‘Your Eminence,’ and we would sign with, “We love you…” That’s how simply we were taught to address him,” Dmitry says.

Dmitry recalls how Vladyka John would give him and the other altar servers gifts on Pascha: Dmitry, as the oldest, would get five dollars, his brother—three dollars, and the rest—two dollars. It was the same money that Vladyka would receive from the donors for whom he prayed so long and tirelessly during the Cherubic Hymn.

With an icon in a packed tram

Vladyka John would stay here, on the second floor of the memorial church during his stays in Belgium.

Vladyka John would stay here, on the second floor of the memorial church during his stays in Belgium.

During his stays in Belgium, Archbishop John would often visit the sick in the hospitals, and not just his own parishioners, but also people whom he would learn about from someone. Dmitry recalls how when his brother was in the hospital in Holy Week, Vladyka wanted to visit him. He was always allowed in, at any time. He didn’t use a car; he didn’t have a driver. Rather, the Archbishop would ride the tram, in his cassock. “Imagine, in a packed tram, an old man, a little strange for the locals, with an icon!” says Dmitry.

During his stays in Belgium, Archbishop John would often visit the sick in the hospitals, and not just his own parishioners, but also people whom he would learn about from someone. Dmitry recalls how when his brother was in the hospital in Holy Week, Vladyka wanted to visit him. He was always allowed in, at any time. He didn’t use a car; he didn’t have a driver. Rather, the Archbishop would ride the tram, in his cassock. “Imagine, in a packed tram, an old man, a little strange for the locals, with an icon!” says Dmitry.

This icon was the Kursk Root Icon of the Mother of God. When Vladyka John traveled, for example, from one church to another, he would wear this icon in a case over his shoulders, recalls Dmitry. The Kursk Root Icon, found in the thirteenth century during the Tatar-Mongol invasion, became the patroness of the Russian diaspora at the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1920, it was taken out of Russia, and since then has been in Yugoslavia, Western Europe, and finally in the U.S., where it is still kept today. St. John ended his earthly life before this icon, in Seattle.

Can you bring galoshes into the altar?

As we have already said, Dmitry served with Vladyka in the altar as a child and would help him vest. He recalls that it was a difficult task. St. John was hunched over, and the altar servers also often got mixed up. However, despite their mistakes, the Archbishop would just smile slightly and show them how to do it correctly. He never scolded the boys, or anybody at all, according to Dmitry.

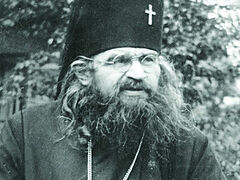

The best photo of St. John, according to Dmitry. From the personal archives of Fr. Leonid Grilikhes, the rector of the memorial church Vladyka John had a large, black wooden staff topped with a knob (as seen in the photo). As Dmitry recalls, it was very interesting for the altar servers to find out why this knob was necessary. Responding to their questioning, the Archbishop once joked: “You know, it’s drawn to the head of little boys like a magnet.”

The best photo of St. John, according to Dmitry. From the personal archives of Fr. Leonid Grilikhes, the rector of the memorial church Vladyka John had a large, black wooden staff topped with a knob (as seen in the photo). As Dmitry recalls, it was very interesting for the altar servers to find out why this knob was necessary. Responding to their questioning, the Archbishop once joked: “You know, it’s drawn to the head of little boys like a magnet.”

There’s another story connected with Vladyka John’s famous staff. According to the Church typikon, only the Patriarch can carry his staff into the altar. Dmitry tells us how one time, while he was serving with Archbishop John, the acolytes forgot about this rule and brought the staff into the altar. When Vladyka saw it, he, again, didn’t scold the boys, but simply said: “What, so next time you’re going to bring my galoshes into the altar?”

Remembering Vladyka John, Dmitry notes his piety, humility, and at the same time simplicity and special humor—“the humor of a holy man,” as Dmitry calls it.

For Dmitry Gering, Vladyka was and is one of the most extraordinary and radiant people he’s ever met in his life. Vladyka is smiling in what Dmitry considers the best photo of him.

St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco is remembered and loved throughout the world. At the recent Seventh World Congress of Compatriots in Moscow, people even called for St. John to be named the patron of the entire Russian diaspora. Archbishop Simon shares this idea. “I think it’s a good initiative,” he says. “It would unite all Orthodox Christians living in Western Europe. There are still people who knew and remember Vladyka.”