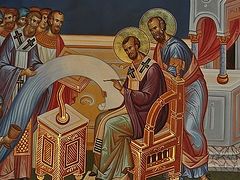

Illustration for the tale, “The Dead Princess”

Illustration for the tale, “The Dead Princess”

How can we help our children learn not just to read, but to love reading? How can we bring true literature, and not just books with letters, into our lives and homes? This is a relevant matter, and every year in our fast, “high-tech” age it seems to get more difficult. Let’s try and look at these questions a little closer and from a practical point of view. Let’s see how Alexander Pushkin1—the “sun of Russian poetry”—can enter the life of a family and how children and teenagers can make friends with him in such a way that it would be interesting for their parents. Of course, everything said below is from very personal experience, and I don’t want to say that it’s a universal approach. Literature is an intimate thing, as indeed is the life of every family. Such stories ripen for a long time, grow slowly and bring forth different fruit.

Pushkin and children

There are some children’s books that adults are not interested in reading at all, and considering a boring duty. Someone said that parents should read to their children—it’s part of the culture, it develops children, and “we are supposed to do it”. A tired, unhappy father after a hard day’s work is forced to read a silly story about some ridiculous piglet to his three-year-old toddler—for the fourth time in a day, for the 230th time in the last six months. The child sees that his parents are sick and tired of it.

If “reading aloud to a child” is a parent’s boring duty, will a child have a chance of truly loving books? Will the culture of reading become his culture? Why not? There are always such chances. But in order for them to be real, reading alone is of course not enough. It seems to me that the ideal option is when the parent himself really wants to read a particular book. This reading can be perceived as, “I am a good mother, reading aloud to my child.” In this case, reading to children can be part of the ritual of “putting them to bed”. It can be a form of communication between parents and children, a form of spending free time together. But at the same time, it will also be a break for parents—a rest, and not a burden. And the child will not just see the book and hear some sounds. First of all, he will understand an important idea: Reading books is interesting and great, and grown-ups love it.

We all have our book preferences. Parents are often interested in books that are designed specifically for little ones. For example, when I read Suteyev’s2 fairy tales to my first child, I recalled my own childhood, with the same stories and illustrations. All this was a joy for me. But the same author day after day, year after year for almost twenty years on end will bore even his fans.

But there are books that seem to be interesting to read always, at any age, and in almost limitless quantities. For example, children’s books that are simultaneously oriented to adults: Lewis Carroll, C. S. Lewis, and Tolkien. But Pushkin’s fairy tales are above all these, and valid for all times.

It seems clear why the writings of Alexander Pushkin are useful and almost obligatory for children to read. These are not just twisted plots—this is genuine poetry, this is the Russian literary language.3 If a particular fairy tale strikes a child’s fancy, he will ask to read it again and again—this is how vocabulary culture and literary tastes are formed, even for a three-year-old. Little children can easily, automatically memorize fragments of a fairy tale, and so they become familiar with genuine Russian literature.

But actually I would like to talk about why and how it can be interesting for parents to re-read these fairy tales.

Deep convictions

When my eldest child was three, he was very fond of Pushkin’s fairy tale, “The Dead Princess and the Seven Knights”. Its title sounds precarious, especially from a toddler:

“Mom, read me the ‘Dead Princess’!”

“We read it twice yesterday. Let’s read “Tsar Saltan”.”

“No, I want ‘The Dead Princess’!”

I read it over and again. The younger child was falling asleep, while this one, already sleepy, whispered the words, repeating after me:

Tsarevitch Yelisei,

Having Prayed earnestly to God,

Is setting out his journey…

When I was just about to pretend that I had lost the children’s favorite book, fortunately for me, the time had come for my next hermeneutics term paper on literary criticism. What material should I prepare my work on? It dawned on me that I should use Pushkin’s fairy tales—at least some benefit would come from this endless reading. I picked up a pencil, and each time while reading to the children I marked the fragments of the tale I needed in the book margins. And it turned that out I had to read and re-read these, checking the correctness of my assumptions and conclusions, finding key themes and analyzing them... More and more layers opened up to me, amazing connections with Pushkin’s other works. Different social movements and the Gospel were revealed. It turned out to be extremely interesting.

Over time, as the children were growing up, my husband and I discussed these extremely important things with them. Sometimes the answer to a child’s question or a conversation on a specific topic can lead to literature, and indeed to Pushkin’s fairy tales, as a clear illustration.

For example, the theme of envy.

It is in his fairy tales that Pushkin with surprising subtlety and accuracy shows how jealousy destroys relationships between people, families, and states, and kills a jealous man’s soul. The evil stepmother decides to kill the princess because she was “full of black jealousy.” The weaver and the cook also resorted to killing their sister and nephew because “they are jealous of the king’s wife.” Pushkin vividly and clearly shows how jealousy is born and how it works. It is possible and necessary to develop a theme and draw it out in depth; both parents and children can master all this while reading Pushkin’s tales. Even very young children can be told about jealousy, as well as many other things from the example of these tales.

Or another topic: marriage.

This is a prevailing theme in Pushkin’s writings, especially in the mature period of our great poet’s creative work. It is a truly Christian and Orthodox theme. What is important and interesting is that in “Tsar Saltan” and “The Dead Princess”, Pushkin talks about marriage in a way that it can and should be discussed, even with young children. Here is a tiny episode. The seven knights ask the princess to choose one of them as her husband. And the princess replies:

I’ve no choice—my hand is promised!

You’re all equal in my eyes,

All so valiant and wise,

And I love you all, dear brothers!

But my heart is to another

Pledged for evermore. One day

I shall wed Prince Yelisei!4

This theme is the same in Eugene Onegin, but in a different way:

But I am given to another

And will be faithful to him forever.

The idea of fidelity, that marriage and even the promise of marriage is sacred, precious, and forever, is something I think we can teach even to small children. When they become adults, it may be too late...

But in Pushkin’s fairy tales there are many other very important themes that constitute the foundation of our entire Russian Orthodox civilization. For instance, the theme of the king/tsar and the kingdom. Highlighting key words and making a detailed, step-by-step analysis allows us to see such non-trivial aspects of this theme that we will want to read these fairy tales to our children over and again—not just to put them to bed, but also because we ourselves are interested. We read to our children slowly, almost in a singsong voice, with a pencil in our hand. As the children fall asleep, we ourselves have something to ponder.

The texts of such great authors as Homer, Shakespeare and Pushkin can indeed be read every year. You can re-read them many times and discover something new each time. It seems that I have read all of Pushkin’s works a thousand times. One of our homeschooled children is now in second grade, and the curriculum requires the study of Pushkin’s tales. We sit down together, I read aloud, and the child listens. We read a very small fragment at a time, discussing everything—who, where, why, and what for... Suddenly I see a surprising thing: The “evil queen” is taking a selfie! “Yes, mom, she’s taking a selfie!” my child exclaims.

Fantastic! This is a real prophecy about Instagram. Or maybe there is nothing new under the sun?

So, the queen looks into her magic mirror—a little thing where she sees her own face. The thing with an image of the queen’s face says: “You in all the world are the fairest and your beauty is the rarest.”5 Let’s imagine a smartphone instead of her mirror.

The queen monitors her social networking site where she posts her pictures. And she reads: “You’re the best!”, “Super!”, “Cool!”, “What a gorgeous hairstyle you have!” “Where do you buy lipstick ?!” “I can’t believe it, it’s plastic!”

The queen no longer sees living people around her—she lives in the mirror reality. “Only with this glass would she in a pleasant humor be”, and “many times a day she’d greet it.”6 Her whole world is in this mirror-smartphone, and all her happiness is in enthusiastic comments and “likes”.

And then, suddenly, instead of the usual thousands of adoring “likes”, the queen hears: “You are fair, I can’t deny. But the Princess is the fairest and her beauty is the rarest.”7 This is followed by her anger, rage, and attempts to “negotiate” with the mirror... And then—a crime. Two attempts to commit murder. How does the story end? Again—Pushkin’s very subtle solution. The queen died of anguish. From depression.

I wonder what we will see in Pushkin’s fairy tales in twenty years? What will each of us see while reading fairy tales to our grandchildren? However, this is probably not a prophecy. After all, the passion for selfies, dependence on our friends’ opinion of us, is only a special manifestation of the long-known passions and inclinations that the holy fathers have described for the past 2,000 years. It’s just that our poet-prophet portrayed this obsession with ourselves in an expert and accessible way—what happens when the soul is engaged in narcissism, when it is “stubborn, haughty, willful and jealous.”8 It doesn’t matter what it all flows into, be it social media, pre-internet looking glasses, or something “sublime” and “intellectual”…

It seems to me that all this can and should be discussed with children—even with a six-year-old child, and surely with an eight-year-old. You can think about all this for yourself when you read those bedtime stories to children...