Indeed, it’s hard to imagine that such a peaceful person as the beloved Serbian Patriarch Pavle could get angry—his peaceful spirit, his unyielding adherence to the commandment, “Blessed are the peacemakers…,” doesn’t fit with displays of anger at all. But the nature of anger can vary: There’s anger that causes the sun to set (cf. Eph. 4:26), and there’s righteous anger. Archimandrite Jovan (Radosavlević), a friend and co-struggler of the holy hierarch tells about such anger in his reminiscences of Patriarch Pavle. Here is his short story.

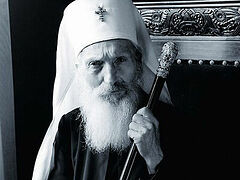

His Holiness Patriarch Pavle (Stojčević)

His Holiness Patriarch Pavle (Stojčević)

During the time of the godless communist authorities in Yugoslavia, Bishop Pavle of Raška and Prizren never went to vote. I remember, sometime in 1970, another “free expression of the will of the workers” was scheduled for a Sunday. Vladyka was headed off to serve in Priština and Gračanica. I accompanied him to the bus stop, and taking his blessing, I asked:

“What should I tell the authorities if they ask (and they will) if Bishop Pavle is coming to vote?”

“Tell them the bishop is out of town and you don’t know when he’ll be back.”

At about 10:00 AM, two policemen came, asking where Vladyka was and when he was going to vote. I told them he wasn’t there, that he was on the road; that I didn’t know when he’d be back. They didn’t believe me:

“We saw him at the diocesan building this morning. He’s definitely there.”

I explained that yes, he was, but I myself accompanied him to the bus stop.

“So,” they said, “when will he be back?”

“I don’t know,” I replied, “and Vladyka himself doesn’t even know.”

Vladyka Pavle returned at about 5:00 PM. He had only just entered the diocesan administration building, put his episcopal staff in the corner and hung up his mantia when those same two policemen burst in, demanding that citizen Stojčević show civic consciousness and take part in the people’s vote. Vladyka quite obviously wasn’t feeling well.

“I just got back,” he said. “I got tired along the way, and I need to rest.”

The policemen left, but another pair showed up ten minutes later, persistently summoning Vladyka to the polling station. He answered them:

“I just told the first pair that I need to rest after a long road. Please, leave me be.”

They also stomped out.

I should note that no matter how tired he was, Vladyka Pavle never rested lying down. He would sit in a chair, reading something, taking some notes, or something like that. After dinner, we usually went down to the yard and either chopped wood, or did some sawing, or loaded coal. But this time, Bishop Pavle sat in the kitchen and took an apple or some nuts and a glass of water. He sat quietly, resting.

About a half hour later, a third pair of policemen showed up with their persistent invitation. This time, Bishop Pavle got up, went out into the hallway, and shouted very sternly and loudly, practically growling, as if reprimanding some ill-mannered children

“Two times already I told you to leave me alone. I just got back from a trip. I have to rest, and this is the third time you’re bothering me already! Please, leave here and tell your people I’m not going to vote.”

I must admit, I’d never seen Vladyka Pavle so stern and angry. I was worried he’d find himself in trouble for such “uncivil” behavior towards the authorities, but thank God, everything died down. A few days later, when I was at Visoki Dečani Monastery, I witnessed a conversation between Archimandrite Makarije (Popović) and Milo Vujović, the head of the regional branch of the State Security Administration of Yugoslavia. This is what Vujović said:

“Most of all, I’d like to know what your Pavle thinks about us, the communists.”

I immediately recalled how Vladyka Pavle drove out the policemen, how he didn’t go to the polling station. When I returned to Prizren, I told Vladyka about this conversation. I felt like I had to tell him about it, about how the godless authorities’ thought about him. But instead of gratitude, Vladyka Pavle said very sternly:

“Not a word about it. I don’t want to know!”

He was very careful in his words and rarely told anyone his thoughts about the communists. Sometimes he would tell us:

“I don’t want to get involved with anyone from the authorities; I don’t want to get involved in their affairs, or ask for their services so I could later be lured by them; I don’t want to be ‘in their pocket.’ Therefore, I entreat you, watch yourself—what you do and say.”