Part 1. “I Should Kill You—You Know Communism Better Than Me!”

We continue the recollections of Archimandrite Jovan (Radosavlević), a friend, companion, and co-struggler of the Serbian Patriarch Pavle. Fr. Jovan published his recollections in the book Memories, printed at Rača Monastery in 2018. Here are a few stories that tell about how a person uses his own freedom—either for the glory of Christ, or against Him, to his own detriment.

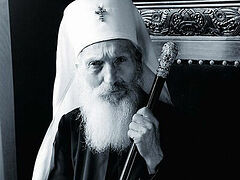

Archimandrite Jovan (Radosavlević)

Archimandrite Jovan (Radosavlević)

Our gentle “Prophet Mitar,”

or following Christ…

One day, as Fr. Pavle and I were passing through the villages of the Ovčar-Kablar Gorge, a forester stopped us and asked what monastery we were from.

“From Rača Monastery,” we answered.

“Tell me, please, does the prophet Mitar live in your monastery?” came the simple and quite unexpected question.

“We have a novice named MItar, sure,” said Fr. Pavle. “But as for him being numbered among the prophets, that we don’t recall.”

“Yes, but if it was Vladyka Vasilije that sent him to you in the monastery, that’s definitely him!”

We confirmed that the novice Mitar was indeed sent to us with the blessing of Bishop Vasilije, but we asked this forester to explain why he called him a prophet, which he did simply and guilelessly:

“Mitar is from Bosnia. I was born there. When he was ten, he became terribly ill and couldn’t move in his bed. He was sick for a long time, with no hope of recovery. One day his mother glanced into his room, and to her horror and amazement, she saw the teenager … sitting on the bed, loudly praying to God. She ran to her son with wobbly legs. She was choked up and wanted to help him, and he cheerfully told her that he was completely healthy. Then he told her that when he was praying to Christ in his heart, as was his custom, and the Lord Jesus Christ Himself appeared to him together with the apostles. They looked into his room from outside through the window, and Christ said: ‘We have come to help you get better. When you get up, tell people to repent and guard themselves from godlessness.’

“This miracle couldn’t go unnoticed in the village and district, and people started coming to his house where he lived with his mother. And, in his childlike way, as much as he could, he called all his guests to what he heard from Christ, that is, to repentance and faith. The number of guests grew with every day, and of course, the authorities found out about Mitar. They immediately burst into his house and sent Mitar to Sarajevo, to a correctional home for young offenders, to nip any contacts with believers and all conversations about faith and Christ in the bud.”

But, through the efforts and intercession of Bishop Vasilije, Mitar was freed and sent to Rača Monastery. After speaking with him seriously, Fr. Pavle was convinced that the young man truly had some kind of Heavenly gift and truly longed for and aspired to monasticism. Mitar already knew many prayers by heart then, especially to the Most Holy Theotokos, and he could always be seen at prayer in the church. He had a pure, childlike soul. We never saw Mitar irritated, angry, or offended by anyone. Usually, when Fr. Pavle saw that the young novices had done something wrong, he instructed them, reproached them, and gave advice for correction, but he was always good-natured and affectionate with bright Mitar. Even when Fr. Pavle blamed him for something in the monastic way, “provoking” him as they say, he always looked upon his strict mentor with a childlike smile, which completely disarmed him—Mitar never had any enemies or anyone who was offended by him.

Later, when Fr. Pavle became Patriarch, well remembering this wonderfully gentle man, he sent Mitar, by then Igumen Avvakum, to Sarajevo during the war in Bosnia, to help the Orthodox Serbs. Then, in the 1990s, there were practically no priests left in Bosnia, and the Serbs who remained alive were suffering and without pastoral care. I have to say that many, to put it mildly, were surprised by Patriarch Pavle’s choice. They thought he sent him to certain death—how could a man who “only looks to Heaven” help others in a war? But the kindness of Igumen Avvakum, his pure and sincere childlike soul, without any involvement in the political passions then or today, helped him in that terrible time of war to carry the Gospel word and the love of Christ to everyone, without exception. Everyone, without exception. I think these qualities and the help of God saved our “Prophet Mitar,” our Igumen Avvakum, and in addition, we were convinced of the wisdom and faith of our Patriarch Pavle.

And the renunciation of Christ…

A sorrowful example to the contrary—the rejection of Christianity and the monastic life—was seen once in our former novice Grujo. One day, during trapeza, someone literally burst into the monastery kitchen straight off the street. He was a young man, black-haired, strong, broad-faced, and yelled from the doorway:

“God help you, honorable fathers. Will you accept me into your monastery?”

The fathers answered:

“We’ll take you, but first tell us who you are and where you’re from.”

The newcomer told a little about himself and went to talk with the abbot and Fr. Pavle. When their conversation ended, Fr. Pavle said:

“Grujo, here’s the deal: Go home and think carefully about life in a monastery, about monasticism. Think about it for a month or two, then come.”

Grujo appeared again a month later. They accepted him as a novice. He burned with zeal in the first days—he didn’t miss a single service, a single obedience. He would finish one job and immediately demand another.

“Grujo, sit down, rest. There’s no rush,” the abbot would say. Grujo would sit down for a minute, but then he would immediately jump up as soon as the bells would ring. He would be one of the first at the services.

The monastery brotherhood took part in public works—repairing the road from Drina to Bajina Bašta. There were many people, including many young people. Grujo was responsible for the water. He carried buckets and poured it out for the workers. He poured everyone a mug and held it out for them, but when the girls came for water, he would intentionally turn away from them, smiling secretly. We were puzzled by this.

One day a diplomat from the Indian embassy came to the monastery. He had had a son, and he invited an Orthodox priest from India to baptize the baby in our monastery. After the Baptism, the distinguished guests looked around the monastery, learned about its history, and at the end asked to be photographed with the abbot and Fr. Pavle and the entire brotherhood. Fr. Pavle called for Grujo, who was working in the field. He answered the novice who came for him:

“Tell Fr. Pavle that it’s not unto my salvation.”

They took the photo without him, but Fr. Pavle, as the teacher of the monastery’s students, was indignant about such indolence and demonstrative disobedience. Already sensing the disorder in the novice’s soul, he suggested that he leave the monastery. But the abbot appointed him some penance, and with that it all ended.

Then Grujo went into the army, where he met and became friends with some Pentecostals, went to their meetings and services. He also met some Muslims. When he returned to the monastery, we saw that he had completely changed: He hardly went to the services, spending most of his time at a bistro, listening to the news and music. He began to criticize and abuse Orthodoxy. “Communion isn’t the Body and Blood of Christ. Christ isn’t God, but a man. Mary isn’t the Theotokos, but just the mother of a man. You can’t venerate the Cross, icons, and relics,” and so on. We saw that talking with sectarians in the army distorted his soul beyond recognition.

Then Grujo went into the city to the Party Secretary and asked him to find him a job. He agreed and joyfully sent him to Belgrade to work as a stoker on the railroad. The former novice worked there for several days and decided it wasn’t for him. He began throwing himself into various monasteries as a repentant sinner, then to factories, plants, and so on. Because Fr. Pavle, he was studying in Greece, and later became a bishop, he couldn’t keep track of Grujo anymore.

When we saw the former novice in Kosovo and Metohije, at the Monastery of Visoki Dečani, he was already a Baptist—he came to us with a typical and familiar blasphemous “sermon.” Since we remembered him from the old days, we started talking with him in a friendly manner. We tried to explain his “bewilderment” to him, referring to the same Bible he was using to “refute” us. But he simply wouldn’t hear it anymore—he kept repeating his “reasoning” endlessly—no reasonable dialogue was possible with him. Then the old and blind Fr. Makary broke down and said: “Oh, my Grujo! Believe me, if there should be a storm, I wouldn’t hide under the same tree as you—God would kill us both!” We couldn’t help but laugh. Thus, this “debate” was finished with a sad smile. Later, poor Grujo joined the Muslims.

Having learned about everything upon his return, Bishop Pavle appealed to the reason and conscience of this man several times, asking him, even begging him to be honest with himself and with God, and he wrote him letters. But Grujo answered him very rudely. Thus, we were bitterly convinced that this was no longer an Orthodox Christian before us, but a Judas. Vladyka Pavle had no other choice but to excommunicate the unfortunate man from the Church.

Thus we see that any congregation has not just wheat, but also tares—they can be in the Church and in monasteries. These tares lose faith, Christian behavior, and you will have to admit that you no longer see a brother in Christ before you. The Gospel says about this: But if he neglect to hear the Church, let him be unto thee as an heathen man and a publican (Mt. 18:17).

How the future Patriarch and other monks were gathered to fight

After the end of the war in 1945, Josip Broz Tito, the new leader of Yugoslavia, really hoped that the Italian city of Trieste would be annexed to the country he and his associates were leading. He was counting on help from the allies—the USSR and Western countries—and was ready to continue the war to achieve this goal. But Trieste was declared a neutral international zone, which greatly disappointed Tito. Then in 1951, he announced a general military mobilization and exercises to show readiness to continue the war with the goal of annexing this Italian city and its surroundings. Thus, all of us who were conscripted earlier fell under this mobilization, and in our district in western Serbia alone, it was said that about 100,000 soldiers of various ages gathered. The responsible officers came and started listing the villagers who were liable for military service, including monks. One Major sat under a tree and wrote down who we were, where we were from, and so on. We were standing in the general line with everyone else. When it was my turn, he asked:

“And who are you, with your long hair and beard?”

Rača Monastery in honor of the Ascension of the Lord

Rača Monastery in honor of the Ascension of the Lord

I responded that I was a monk of Rača Monastery.

“What? What do you mean a monarch?!”1 the Major shouted and started swearing horribly. “We’ve been fighting against the monarchy with our comrades for four years, we have shed blood, and you’re not just a monarchist, but you’re aiming to be a monarch?! To kill you wouldn’t even be enough, you enemy of the people! Enemy!

We monks understood that these words could cost us dearly. But the unbalanced Major was reassured by the Chairman who knew us:

“Comrade Major, he’s not a monarch, but just a student from a monastic school from a local monastery. There’re several of these students here.

“He should have said he’s a student! I have few words for monarchs!”

We were ordered to report to the meeting point, taking a day’s worth of food and a bag for civilian clothing with us—they would give us a uniform at the meeting point. I could see that the matter was serious. Would there really be a war again? We gathered from all the cities and villages of our district, which became a military district. The weather was terrible: November, sleet, wind, mud. People, equipment, horses, artillery—all mixed up together. I saw that many horses had died of cold and hunger, therefore I asked for a post taking caring of the ones that were left—the commander joyfully agreed.

The next day I saw a group of forty people coming down the road, with rifles on their shoulders, but everyone in cassocks, and between them, Archdeacon Pavle (Stojčević). On one shoulder a rifle, on the other—a stretcher for the wounded. Apparently, they were assigned to the medical battalion. “We’ve become soldiers,” they said.

The exercises and maneuvers lasted eight days. I remember one of the last days when our column was overtaken by an important officer on horseback. He stopped and ordered: “Attention!” Our column stopped. The commander walked along the column, examining the soldiers and feeding the horses with lumps of sugar. He saw our “priests’ platoon,” came up close to me and, smiling mockingly, asked:

“What kind of wonder are you, hairy and bearded?”

We had already become friends with the other soldiers, already knew one another, and helped as we could. And before I could answer this officer that I was an “underofficer of the People’s Army of Yugoslavia,” the guys shouted with one voice:

“You go die, comrade Colonel, and you’ll see what kind of ‘wonder,’ will be reading prayers by your head!”2

The Colonel didn’t want to give up:

“Give him a mirror—let him admire himself!”

“We like him without a mirror!” the others said. The Colonel’s face sunk, realizing that his jokes weren’t going to have any impact, and he retreated. I sincerely thanked the guys who stood up for me, but I said that as a monk, it would be better for me to be humble and bear it.

“Radosavlević, why do you feel sorry for him? He doesn’t feel sorry for you! It serves him right!” they said.

On the last day of the exercises, we were in a school equipped with barracks. There was straw on the floor, and we couldn’t even feel our legs from exhaustion and fell fast sleep. How Fr. Pavle, who was in poor health, withstood this ordeal, I don’t know. But he never complained. Moreover, being always disciplined and following instructions exactly, which helped him in any group, he had a great sense of humor, which was very much appreciated by the other soldiers.

Then we were told that the maneuvers were successful and we could go home, which we were happy to do. On the way to the monastery, we visited old priests in several villages and had a good night’s sleep. Then we changed into our normal monastic clothes, cleaned and ironed by our host, and went to our monastery.

Part 3. “Father, Go Hang Yourself!” or the Beginning of His Ministry in Kosovo