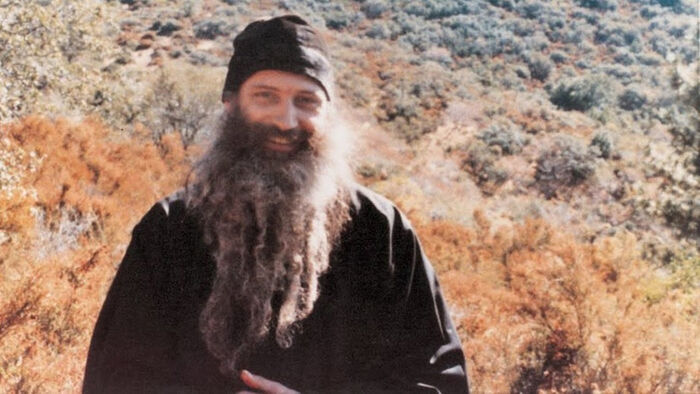

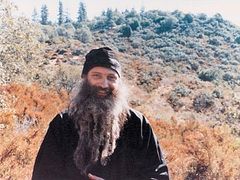

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the repose of Hieromonk Seraphim (Rose) of blessed memory.

Much has been written about this ascetic struggler and patristic-minded teacher of twentieth-century America. The biography penned by Abbot Damascene (Christensen), Father Seraphim Rose: His Life and Works,[1] is an exhaustively researched rich source of information about him. After reading the 1,100 or so pages, you almost feel like you personally knew him.

Fr. Seraphim authored numerous books and countless articles on a variety of topics, which have been widely read, discussed, and dissected. His life and teachings have touched the lives of thousands, if not millions, and not only in his native America, but throughout the whole of the Orthodox world.

While Fr. Seraphim is best known for his teachings and the life he spent in his rugged California monastery, there is one aspect of his life that garners comparatively little attention, but which I have always found to be one of the most touching parts of his life, and that is his beautiful friendship with Alison Harris.

Fr. Seraphim, then Eugene, first met Alison in November 1952 while studying at Pomona College in southern California, and she quickly became his closest friend. While the two had a common group of friends, Alison was the only one to whom Eugene could truly open his soul. She is the only one who understood him, and their friendship continued until the day Fr. Seraphim died, and beyond, long after their last meeting on this earth.

Fr. Ambrose (Young) (known as Fr. Alexey before he became a monastic), one of Fr. Seraphim’s closest disciples, somewhere says that though he was close to Fr. Seraphim, they weren’t friends—theirs was strictly the relationship of a spiritual father to his spiritual child. In fact, most of what we know about Fr. Seraphim comes from his spiritual children or his monastic co-struggler Fr. Herman (though Fr. Seraphim also kept a spiritual journal for a time and a monastery chronicle).

Alison in 1953 Thus, we can say that Alison is the one person who shows us Fr. Seraphim as a friend, though of course, for someone like Eugene/Fr. Seraphim, any true friendship is also a spiritual relationship.

Alison in 1953 Thus, we can say that Alison is the one person who shows us Fr. Seraphim as a friend, though of course, for someone like Eugene/Fr. Seraphim, any true friendship is also a spiritual relationship.

Unfortunately, among those little-acquainted with his life and teachings, Fr. Seraphim sometimes has a reputation as a cold and unbending fundamentalist. However, those who have read his life and works, including his letters to his spiritual son Fr. Alexey Young, know that Fr. Seraphim was a man of pastoral sensitivity, of a deeply loving heart—and his friendship with Alison is a moving testament to this truth.

Moreover, as Fr. Seraphim’s dearest friend from the days before he embraced holy Orthodoxy, it is Alison who helps us to see the amazing transformation that he underwent on his path to the Church.

Eugene and Alison were alike in some ways—both quiet and deeply lonely, given to pondering serious matters. On the other hand, Alison was a devout Anglican, while Eugene, having already long lost the Protestant faith of his middle school years, was a self-proclaimed atheist; though Alison could see that Eugene was, in fact, on a spiritual quest.

“We understood each other,” says Alison. “Both of us were people who found it very difficult to be understood by others. We were both solitary and uncomfortable around others. We didn’t feel much need to explain ourselves to each other—we always seemed to understand without any explanation. We did not have to put on a mask or justify ourselves to each other.”

And while they confided their deepest selves in one another, their friendship was also beyond words. Theirs was not a superficial friendship thriving on constant small talk about frivolous matters. They could be comfortable even with hours of silence, just being with one another.

They had a tradition of listening to Bach’s Ich Habe Genug, with not a word spoken between them. Eugene was deeply moved by the cantata, but it was something he only shared with Alison. If anyone else was there, he wouldn’t play it. And when their friend Kaizo Kubo, whom Eugene greatly respected, committed suicide, Alison simply walked with Eugene for hours, offering silent comfort and support.

In fact, Eugene was able to reveal to Alison that he himself was suicidal, feeling rejected by people in general, including his family. Nevertheless, she could see that “inside he was very, very passionate… not in a worldly sense, but in a spiritual sense.”

And Alison was undoubtedly an important person in Eugene’s spiritual development. In her he saw a devoted Christian whom he could respect, and the time that they spent together listening to Ich Habe Genug, dedicated to the feast of the Meeting of the Lord, had a profound impact on him. Alison would later reflect that it was Bach who gave Eugene Christ.

And we see in their friendship an image of a true friendship, founded on a love of truth and the desire for what is best for the other. Unlike many friendships that would simply shatter were one friend to criticize or offend the other, or were they to speak their minds to one another, Alison could speak frankly with Eugene about his philosophical and spiritual ideas.

She saw the deep pain that lived in his soul because he hadn’t yet found the truth, and she also saw that things like his college infatuation with Zen Buddhism were merely distractions, not entirely serious pit stops along his true path. She understood that he had “substituted studying for direct apprehension of truth.”

Alison told him directly: “Zen [is] a lot of nonsense… Christianity (more specifically Catholic Christianity) [is] the only truth worth having.”

“Zen helped Eugene in a negative way,” Alison later said. “He went into it with the idea of finding knowledge of himself, and what he found was that he was a sinner. In other words, it awakened him to the fact that he needed something, but provided no real answers.”

In fact, it was Alison who introduced Eugene to Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov as part of her efforts to convert him to Christ and provide him with the real answers he was so desperately seeking.

Alison was witness to how his quest for truth and his suffering for lack of it unfolded. One of the most striking scenes from Fr. Seraphim’s pre-Orthodox life is the night when he began shouting at God in a drunken rage, daring Him to kill him. Alison understood that Eugene would prefer to be struck dead, for then at least he would know the truth, rather than continue in a state of unknowing. Eugene was always such an all-or-nothing person she later reflected, and this certainly continued in his days as a monastic struggler.

Sometimes Eugene would drink heavily and weep from despair, but only Alison saw the weeping. His other friends simply thought he drank for “recreation.”

And it was Alison who saw how the words of Bach’s Ich Habe Genug, taken directly from Scripture, washed over him and began to affect an internal change in him. And as we have said, this was a bond he shared only with her.

Eugene at his graduation from Pomona in 1956

Eugene at his graduation from Pomona in 1956

The friends kept in touch after they left Pomona, though the letters he sent her in his early days in San Francisco (where he had gone to study eastern religions after Pomona) were so dark and depressing that she burned them.

However, it was also in San Francisco that Eugene’s search for truth would lead to his first encounter with Orthodoxy, and where the seeds planted by Alison and Bach years earlier would truly begin to bloom. When Alison went to visit Eugene at his parent’s place in Carmel over Christmas break in 1959, she was overjoyed to spend time with the new Eugene.

Alison had been praying for Eugene every day, and since becoming a Christian, Eugene had been praying for her daily as well. Their friendship had remained strong, and her visit was full of the quiet walks and the classical music that had marked their time together in Pomona.

The bond between them was so strong that Eugene’s mother even initially suspected a budding romance. Though this was not to be, Eugene did later speak to Alison about the two of them getting married and having children. Alison later said: “Although he talked at length about marriage and all that it would involve, he knew deep down that he was not going to get married. But he cared for me, and wanted me to know that.”

And just as she had years later, Alison gave Eugene frank direction for his spiritual life. By the time of her visit in 1959, he had been interested in Orthodoxy for quite some time, but in typical Eugene fashion, he was slow to make a decision and had not yet been received into the Church. “You can’t just go to church and never do anything about it,” she told him. “You need to be baptized or confirmed as a member because you need the Sacraments.”

And just as Alison always showed concern for the state of Eugene’s soul, it was now his turn to return the favor. Now that he had found Orthodoxy, he was eager to share its beauty and truth with her, and she attended an Orthodox Liturgy with him during her visit to Carmel.

Eugene had no interest in worldly matters. He cared only for the Truth and for sharing that Truth with his dearest friend. Their friendship had always been a deeply spiritual one, only now Eugene realized that the true foundation is Jesus Christ.

It was half a year later in the summer of 1960, when Eugene visited Alison in Long Beach, that they would speak of marriage. And in fact, it was to be the last time they ever saw one another in this earthly life. Alison understood that Eugene was embarking upon an entirely new life. At the same time, they remained in contact, and his zealous concern for the soul and salvation of his friend was the focus of the letters he would continue to send her.

A year after he was received into the Orthodox Church in 1962, Eugene wrote to Alison:

When you last heard from me I was very near to the Russian Orthodox Church, though still somewhat uncertain; and though I had renounced the worst of my sins, I still lived very largely as the world lives. But then, unworthy as I am, God showed His path to me. I became acquainted with a group of fervent Orthodox Russians, and within a few months (it was, significantly enough, on the Sunday of the “Prodigal Son” just before the beginning of Lent) I was received into the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile, whose faithful child I have been for a year and a half since then. I have been reborn in our Lord; I am now His slave, and I have known in Him such joy as I never believed possible while I was still living according to the world.

In another letter to Alison, Eugene wrote of his unwavering love for her, of spiritual friendship, and of his ardent desire that they might be together in the Kingdom of Heaven:

In reading your letter over again, I see that you say, “Your life is now complete, and you have many friends a great deal dearer than I. I am not one of you.” But that is not true. As a matter of fact, I have very few close friends; but that is not what I mean. Spiritual friendship (and every other kind, while having its consolations, ends with death) does not require the conditions (common activities or work, a common circle of acquaintances, frequent meetings, etc.) without which worldly friendships simply evaporate. Spiritual friendship is rooted in a common Christian faith, is nourished by prayer for each other and speaking to each other from the heart, and is always inspired by a common hope in the Kingdom of Heaven in which there shall be no more separation. God, for His own reasons, has separated us on earth, but I pray and hope and believe that we shall be together when this brief life is over. Not for a single day have you been absent from my prayers, and even when I heard nothing from you for two years and thought perhaps I would never hear from you again, you were still closer to me than most of the people I see frequently. Oh, if we were real Christians, we would be strangers to no one, and would love even those who hate us; but as it is, it is all we can do to love a few. And you are certainly one of my “few.”

And this closeness never waned. In fact, in late summer 1982, twenty-two years after Eugene and Alison last saw one another, she received a mysterious message from him. She had continued to pray for him daily, and she could feel that he was praying for her. As Fr. Seraphim lay dying in a hospital, he appeared to Alison in a dream: “She saw him tied to a bed and saw terrible physical agony in his eyes, such that it was painful even for her, a nurse, to behold. She saw that he was unable to speak.”

She immediately wrote to the monastery to ask if Fr. Seraphim was okay. In the meantime, Fr. Herman had written to her to inform her of Fr. Seraphim’s repose.

Years prior, Fr. Seraphim had instructed Fr. Herman to contact Alison should anything ever happen to him. Though they hadn’t seen one another for more than two decades, she continued to hold a special place in his loving heart. The saint is the one who opens his heart to everybody, and while Fr. Seraphim had left his former way of life behind, his heart remained open to the people from his former life, and most especially to Alison.

In March 1984, a year and a half after Fr. Seraphim’s repose, Alison even temporarily moved to Redding, California, to be near his grave at St. Herman’s Monastery in Platina. There she received another mysterious communication from Fr. Seraphim. Fr. Damascene writes:

There Fr. Seraphim appeared to her one night, looking as he did when she last saw him in the flesh in 1960. Sitting at the table in the kitchen area of the motel room, he seemed to be actually present in body before her, not like a ghost; and she was not at all frightened. “Eugene,” she said to him, “I thought you were dead.” Fr. Seraphim looked at her with joy. “Don’t you know we’ll always be together?” he asked. These words of assurance remained with Alison for the rest of her life. With them, Fr. Seraphim confirmed posthumously what he had written to her back in 1963: “I pray and hope and believe that we shall be together when this brief life is over.”

Alison reposed on February 12/25, 2002. As Fr. Damascene writes: “According to God’s inscrutable Providence, this was the commemoration day of St. Eugene of Alexandria: Fr. Seraphim’s nameday in the world and the fortieth anniversary of his reception into the Church.”

Her last wish was to be buried on the grounds of St. Herman’s Monastery, to be near her best friend. Alison considered her friendship with Eugene/Fr. Seraphim to be deeper than any other relationship she ever had, even after she was married.

Fr. Seraphim’s friendship with Alison shows us his loving heart, and it serves as a wonderful example of what friendship can be—a spiritual relationship guiding us to salvation.

Alison stood by Eugene/Fr. Seraphim through bad times and good, and she was undoubtedly among the most important influences in his life, leading him along the path to the Good. Perhaps it could be said that without Alison, there would be no Blessed Seraphim.