The Chora Church, Istanbul. Photo: Nikita Bazurina.

The Chora Church, Istanbul. Photo: Nikita Bazurina.

Today, the word “icon” has a mainly sacred meaning for us. This is what we call images painted in accordance with the Church canons and then consecrated, of the Holy Trinity, the Lord Jesus Christ, the Mother of God, the angels and saints, as well as sacred events.

Meanwhile, in the ancient Greek language the word ἡ εἰκών (eikōn), from which the word “icon” comes, did not define sacred objects. It is also translated as “image”, “depiction”, “likeness”, and “comparison”.

This is what any picture or artistic image was called—for example, even statues. This ancient Greek word has the same root as the verb ἔοικα (eoika), meaning “to be like”, “to be similar to”, “to pertain to”, “to be appropriate to”. After the acceptance of Christianity in Byzantium, the ancient Greek word ἡ εἰκών was transformed into the word ἡ εἰκόνα (ikona), which then began to define the ecclesiastical, sacred images—that is, icons.

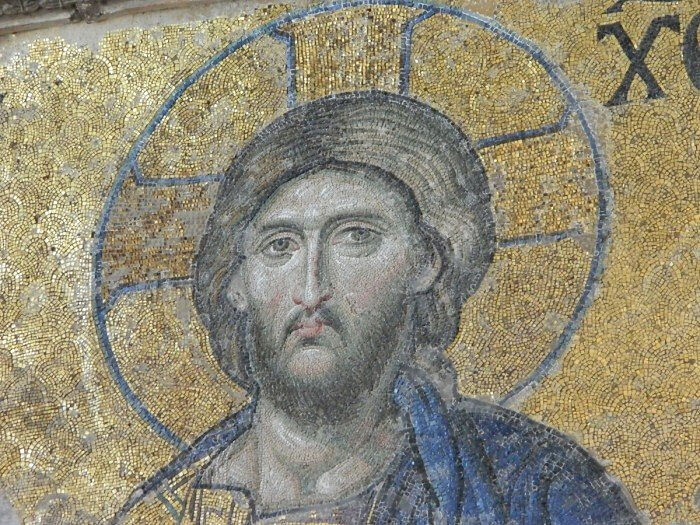

In general, images of Christ, the Theotokos, saints, and sacred events appeared in Christianity during the second century. By the fourth century, the walls of many churches were painted with artistic images.

The Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. Photo: Nikita Bazurin.

The Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. Photo: Nikita Bazurin.

However, as we know, the veneration of icons did not take root in the Church without turbulence. In the eighth to ninth centuries, the heresy of iconoclasm— ἡ εἰκονομαχία (ikonomahia)—spread in Byzantium.

Its adherents, amongst whom were certain Byzantine Emperors and even Patriarchs, considered that the veneration of icons violates the second Mosaic commandment: Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them… (Ex. 20:4–5).

It has to be said that in part, the heresy of iconoclasm arose as a reaction to the extremism of folk veneration of icons, which by that time had to some degree fallen into superstition. So, as with many other heresies, it was an absolutely incorrect solution to a bad situation. At that time there was also for example the widespread practice of using icons in place of a child’s “godparent”, or mixing paint from icons into Eucharistic wine, and so on.

The iconoclasts’ argument in their war against icons was that it was forbidden to bow down to “anything made by human hands”. In theological debates on these themes, those who defended the veneration of icons formulated that it is meet to bow down before icons and venerate them, but not to serve them, because it is meet to serve only God: “We can bow before other than God, because bowing is an expression of honor. But it is forbidden to serve any but God.”

Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. Photo: Nikita Bazurina.

Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. Photo: Nikita Bazurina.

It is interesting that two extremes came together in the heresy of iconoclasm—extreme spiritualism and purely earthly interests. On the one hand, as the iconoclasts would say, the Godhead cannot be fully depicted, and He must not be “insulted by irrational and dead matter”. On the other hand, the heresy of iconoclasm also received support from a governmental-political and secular point of view in the context of the Byzantine emperors’ war with monasticism. The monks in no way wanted to depart from the veneration of icons, while Emperors Leo III the Isaurian (717–741) and Constantine V Copronymus (718–775) considered that the monasteries were attracting too many material and human resources, which could have served the empire in its numerous wars with the barbarians.

And this fierce war with icons perhaps would not have happened if it had not been bound up with material and state interests. In warring with monasticism, the iconoclast emperors’ fury grew against icons along the way. Incidentally, a real stronghold of iconoclasts in the war against “icon-worshippers” was the Byzantine army and military.

Nevertheless, the fierce struggle against icons, which was waged for the secularization of life and culture in society and worldly interests, led to a significant impoverishment of culture. Icons were destroyed that were outstanding artistic masterpieces, and the walls of churches were painted over with arabesques and vignettes consisting of birds and flora, the artistic value of which was incalculably lower that the icons they obscured.

A.V. Kartashev in his History of the Ecumenical Councils writes of the “iconoclasts’ sanctimonious and false arguments”, which call for the “discarding of all knowledge and art, given [to man] for God’s glorification”. Iconoclasts rejected “in principle also all human knowledge, theology, and every thought and word as instruments of expressing dogma. This was not only hypocritical and sham barbarism, but also simple dualism that rejected the sanctity of anything material. The Seventh Ecumenical Council rose up in Orthodox manner against these hidden heresies of monophysitism and dualism, and defended along with art, “all knowledge and artisanship as God’s gift for the sake of glorifying Him”. The iconoclasts’ “enlightened” liberalism itself is shown to be obscurantism, and the theology of the Seventh Council is shown to be a blessing on science and culture that is most profound and indisputable.”

In 754 an iconoclastic council was held, which condemned the veneration of icons. This council also anathematized Patriarch Germanos of Constantinople and St. John Damascene, who were stalwart defenders of the veneration of icons. Although the council claimed to have the status of Ecumenical, its resolutions were later rejected by the Church.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council that took place in 787 confirmed the dogma of the veneration of icons. And in 848 there was another Church council that confirmed all the definitions outlined in the Seventh Ecumenical Council, and established the rite of proclaiming the eternal memory of the zealots of Orthodoxy and the anathematization of heretics. This rite is pronounced to this day in our Church on the Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy (the first Sunday of Great Lent).